Outcomes of Employment Discrimination Charges Filed Under the Americans With Disabilities Act

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The outcomes of employment discrimination charges filed under the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) by individuals with psychiatric disabilities and those with other disabilities were compared. METHODS: Data obtained from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) consisted of all ADA employment claims closed as of March 31, 1998. Charges were categorized by whether they were investigated by the EEOC or by a Fair Employment Practice Agency (FEPA). RESULTS: Of the 175,226 charges filed, 83.2 percent were closed by March 31, 1998. Of these, 15.7 percent brought some kind of benefit to charging parties, although only 1.7 percent resulted in new hires or reinstatements. Of charges investigated by FEPAs, 23.3 percent led to some benefit, compared with 11.5 percent of charges investigated by the EEOC. Of charges investigated by the EEOC, the median actual monetary benefit was $5,646, compared with $2,400 for charges investigated by FEPAs. A total of 13.6 percent of charges filed by individuals with psychiatric disabilities resulted in benefits, compared with a benefit rate of 16 percent for persons with other disabilities. The median actual monetary benefit received by persons with psychiatric disabilities was $5,000, compared with $3,500 for those with nonpsychiatric disabilities. Individuals whose charges were investigated in the first three years of ADA implementation were more likely to receive benefits than individuals whose charges were investigated more recently. CONCLUSIONS: Most employment discrimination charges filed under the ADA do not result in benefits or a finding of reasonable cause. Outcomes for people with psychiatric disabilities do not differ substantially from those for people with other disabilities.

The Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) is arguably the most important civil rights law for people with disabilities. It is also the most significant civil rights law since the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (1,2,3,4). It prohibits discrimination against persons with disabilities in virtually every aspect of public life including employment, transportation, public accommodations, and communication.

The definition of disability used in the ADA is sweeping, including persons who have physical or mental impairments that substantially limit them in one or more major life activities, persons with records of such impairments, and persons regarded as having such impairments. The law's employment provisions, which are the focus of this paper, are found in Title I. Title I prohibits private employers with 15 or more employees from discriminating against qualified individuals with a disability in anything related to that person's employment, including the application process, hiring, promotion, and benefits.

A qualified individual with a disability is a person who can perform the essential functions of a position with reasonable accommodations. Such accommodations are required only if making them does not place an undue hardship on the employer. Under Title I, individuals who have been subject to employment discrimination because of disability may file an administrative charge, which triggers an administrative dispute resolution process. They may also file a lawsuit, but only after pursuing administrative remedies.

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has principal enforcement authority for Title I. It shares responsibility with state and local Fair Employment Practice Agencies (FEPAs) for receiving and investigating employment discrimination charges. FEPAs enforce state and local laws similar to federal antidiscrimination laws. The EEOC has 50 field offices in 33 states and the District of Columbia. A total of 125 FEPAs are located in 48 states, the District of Columbia, and two territories.

Generally, individuals may file an administrative charge with either the EEOC or a FEPA. Either way, it may be considered a charge "dual-filed" under both the ADA and any applicable state or local law. FEPA investigations of dual-filed charges under the ADA are conducted under contract with and overseen by the EEOC (5).

Title I has important implications for individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Research has found that individuals with psychiatric disabilities face discrimination from employers and coworkers (6,7,8,9). Moreover, psychiatric disabilities have figured prominently in ADA enforcement. Between July 26, 1992, the effective date of Title I implementation, and March 31, 1998, back impairments were the most commonly cited disability in Title I complaints, followed by psychiatric disabilities. By 1999, psychiatric impairments had overtaken back impairments as the disability most commonly cited.

This paper, which focuses on charges filed by persons with psychiatric disabilities, is part of a larger study of the process of filing employment discrimination charges under the ADA (10,11,12,13). For the study reported here, we used records of all Title I charges filed as of March 31, 1998, and addressed five research questions. To what extent do people who file charges under the ADA benefit from their charge? Are there differences in the extent to which the charge process assists individuals with psychiatric disabilities compared with individuals with other disabilities? What actual and projected monetary benefits do people who file ADA charges receive? Do people whose charges are processed by FEPAs fare better than those whose charges are processed by the EEOC? Have there been changes over time in the outcomes of charges?

Methods

Data and analysis

Data were obtained from the EEOC's charge data system (CDS). The CDS tracks charge processing and investigations and provides informational, statistical, and management reports. Both EEOC field offices and FEPAs enter and update information in the CDS. When data are entered and updated, one copy is stored in local databases and another is transmitted to a computer at EEOC headquarters that consolidates transmitted data, merges submissions, and maintains the database (14).

The EEOC requires field offices and FEPAs to enter information about charging parties (persons making charges) and charges into the CDS. This information contains information about the individual's impairment, race, national origin, age, and gender. Other standard information includes charge filing and closing dates; the EEOC or FEPA office where the charge was filed, investigated, and closed; the alleged violation(s); the charge status—that is, whether it is open or closed; and, if closed, the charge outcome and whether there was a finding of cause.

We report simple percentages of ADA-based charges and charging parties. No significance tests for difference of proportions were conducted because all analyses used data from the entire population of persons making ADA charges. Tests of significance are used with estimates of population parameters derived from samples; thus such testing was inappropriate in this study. Instead, we address the extent to which differences found are substantively important.

Results

Overall outcomes

Between July 26, 1992, the date when Title I became effective, and March 31, 1998, a total of 175,226 employment discrimination charges were filed under the ADA. Of these, 57 percent were filed with EEOC field offices, and 43 percent were filed with FEPAs. Given the large proportion of filings with FEPAs, a comprehensive picture of the impact of Title I requires inclusion of charges investigated by both the EEOC and FEPAs.

ADA charges can be closed in six ways, three of which ordinarily provide direct benefit to persons making charges. Withdrawals with benefits are nonwritten informal agreements between employers and charging parties that resolve a charge before the EEOC or a FEPA has completed its investigation or determined the charge's merits. Settlements are formal written agreements between employers and charging parties that resolve charges before the EEOC or a FEPA issues a letter of determination on the merits. Conciliation agreements are formal written agreements between employers and charging parties that resolve a charge after the investigation has found reasonable cause to believe that discrimination occurred.

These first three types of charge closures typically involve benefits to charging parties. The CDS tracks two types of monetary benefits. Actual monetary benefits are provided by employers through back pay, remedial relief, compensatory damages, or punitive damages. Projected monetary benefits are remedies to be provided by employers during a one-year period through hiring, promotion, reinstatement, or other accommodations that would bring monetary returns.

Three other types of closures bring no direct benefits to charging parties. Unsuccessful conciliations involve a failure to achieve agreement between an employer and charging party after an investigation indicates that there is reasonable cause to believe that discrimination occurred. Determinations of no cause are complaints for which investigators have found insufficient evidence of reasonable cause to believe that discrimination occurred. Administrative closures are charges closed for other reasons without a determination of whether cause exists for the complaint. This category includes cases in which the charging party has obtained a right-to-sue letter in order to file a lawsuit.

As of March 31, 1998, a total of 83.2 percent (N=145,794) of all Title I charges had been closed. Of these, 15.7 percent brought some kind of benefit to charging parties. Charges investigated and closed by FEPAs were twice as likely to benefit charging parties in some way than charges that were investigated and closed by the EEOC. Of the charges investigated and closed by FEPAs, 23.3 percent led to some benefit, while 11.5 percent of charges investigated and closed by the EEOC led to some benefit. Those who received monetary benefits were more likely to receive greater monetary benefits if they filed with the EEOC rather than a FEPA. For people bringing charges through the EEOC, the median actual monetary benefit was $5,646; those whose charges were investigated by FEPAs received a median benefit of $2,400.

We also examined the number and percentage of determinations by the EEOC and FEPAs in which reasonable cause was found to believe that discrimination occurred. Referred to as "cause findings," they are calculated by adding the charges resulting in successful and unsuccessful conciliation. Persons filing with the EEOC were more than twice as likely to have a cause finding than those filing with a FEPA, although the number of such findings is quite low. Only 3.4 percent of the total EEOC investigations and 1.3 percent of the total FEPA investigations resulted in cause findings.

These low percentages are consistent with criticisms that the EEOC makes too few cause determinations (15,16,17). However, some withdrawal-with-benefit outcomes, formal settlements, and administrative closures would have resulted in cause findings if investigations had been carried to their conclusion. In addition, as discussed below, cause findings by the EEOC have increased during the last several years.

Charge outcomes and psychiatric disability

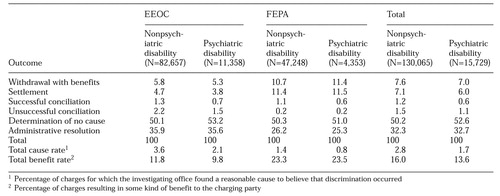

The percentages of cases resulting in some benefit to the charging party—withdrawals with benefits, settlements, and successful conciliations—were calculated. Table 1 shows that 13.6 percent of charges filed by individuals with psychiatric disabilities resulted in benefits, compared with 16 percent for persons with other disabilities. This was primarily due to differences among charges investigated by the EEOC. Those involving individuals with psychiatric disabilities had a benefit rate of 9.8 percent, compared with 11.8 percent for charges involving individuals with other disabilities. Among charges investigated by FEPAs, those involving individuals with psychiatric and other disabilities resulted in virtually the same rates of beneficial closure.

Individuals with psychiatric disabilities were less likely to receive cause findings than individuals with other disabilities. Among investigations by the EEOC, 2.1 percent of charges involving individuals with psychiatric disabilities resulted in a cause finding, compared with 3.6 percent of charges involving individuals with other disabilities. Among FEPA investigations, .8 percent of charges involving individuals with psychiatric disabilities resulted in a cause finding, compared with 1.4 percent for charges involving individuals with other disabilities.

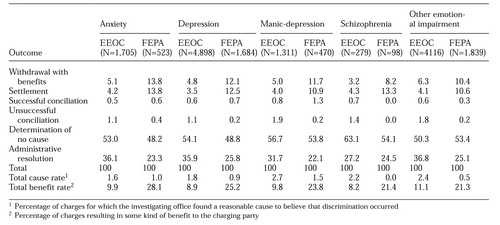

We also compared charges involving people with different psychiatric diagnoses; the results are summarized in Table 2. People with psychiatric disabilities self-report their impairment or diagnosis to the investigator receiving their charge. The CDS allows five psychiatric disability designations: anxiety disorder, depression, manic-depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and "other emotional impairments." Individuals with schizophrenia file relatively few Title I charges. Only 377 charges closed by either FEPAs or the EEOC involved schizophrenia, compared with 1,781 involving manic-depression, 2,228 involving an anxiety disorder, 6,582 involving depression, and 5,955 involving other emotional impairments.

The type of psychiatric disability appeared to have a small effect on the way that charges were closed. For charges investigated by the EEOC, those resulting in benefits ranged from 8.2 percent to 11.1 percent; charges involving individuals with schizophrenia were the least likely to result in benefits, and those involving individuals in the category other emotional impairments were the most likely. For charges investigated by FEPAs, benefit rates ranged from 21.3 percent to 28.1 percent; charges involving individuals in the category of other emotional impairments were the least likely to result in benefits, and charges involving individuals with anxiety were the most likely. However, it is important to note that persons with schizophrenia whose complaints were investigated by a FEPA had virtually the same benefit rate as those in the category other emotional impairments. Individuals with schizophrenia had the highest rates of determinations of no cause for both EEOC and FEPA charges.

Nature and amount of benefits

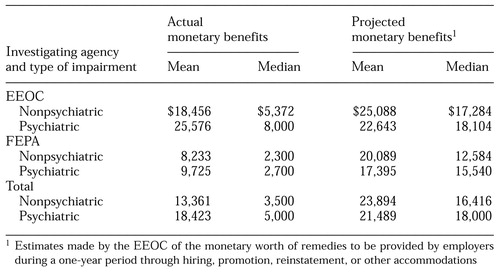

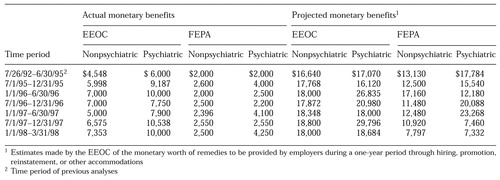

Table 3 reports actual and projected monetary benefits resulting from EEOC and FEPA charge closures. Both mean and median monetary benefits are presented because both are important in describing benefits from ADA charges. As in many economic analyses, the distribution of monetary benefits was skewed. The median is appropriate for understanding benefits received by typical charging parties. To understand the impact of monetary awards received in particularly strong cases, the mean is more appropriate. For both EEOC and FEPA charges, the medians and means of actual monetary benefits and the medians of projected monetary benefits were higher for individuals with psychiatric disabilities than for individuals with other disabilities. However, the means of projected monetary benefits resulting from charges investigated by the EEOC and by FEPAs were lower for persons with psychiatric disabilities than for persons with other disabilities.

Charges investigated by EEOC offices resulted in considerably higher monetary benefits, both actual and projected, than charges investigated by FEPAs. Moreover, when the percentages of individuals who received different kinds of benefits were compared, it was found that charges filed with the EEOC resulted in a higher percentage of monetary benefits—both actual and projected—than charges files with FEPAs. Of the charges investigated by EEOC offices that brought benefits to complainants, 61.4 percent resulted in actual monetary benefits and 27.7 percent resulted in projected monetary benefits. Of the charges investigated by FEPAs that brought benefits to complainants, 59.2 percent resulted in actual monetary benefits and 8.5 percent resulted in projected monetary benefits.

New jobs and reinstatements

Of the EEOC-investigated charges filed by individuals with psychiatric disabilities, 1.4 percent resulted in new jobs or reinstatements; this figure was 2 percent for individuals with other disabilities. Of the FEPA-investigated charges filed by individuals with psychiatric disabilities, 1 percent resulted in new jobs or reinstatements; this figure was 1.1 percent for persons with other disabilities.

Although small differences were noted between people with psychiatric and other disabilities and between individuals whose charges were investigated by the EEOC and by a FEPA, none of these groups were very successful in obtaining new jobs or being reinstated in old jobs. Only 2,407 charges (1.7 percent) resulted in new hires or reinstatements.

Changes over time

Analyses used in our previous studies (10,11,12,13) focused on the period between July 26, 1992, the effective date of Title I, and June 30, 1995. The additional data obtained for the study reported here enabled us to compare charge resolutions from that time period with those from July 1, 1995, through March 31, 1998.

Benefit rates decreased dramatically after the first three years of implementation of Title I. Indeed, the percentage of charges filed with the EEOC involving individuals with psychiatric disabilities that resulted in benefits was slashed in half—from 15.1 percent to 7.9 percent. Similarly, benefits decreased markedly for EEOC-investigated charges involving individuals with other disabilities, from 16.7 percent to 9.6 percent. Benefits also fell for charges investigated by FEPAs that involved individuals with psychiatric disabilities, from 30 percent to 21.6 percent. For FEPA charges involving individuals with other disabilities, benefits decreased slightly from 25.3 percent to 22.2 percent.

Critical to understanding these changes is the June 1995 implementation throughout the EEOC of a new procedure for processing charges. The new procedure changed the EEOC policy of requiring full investigations for all charges—even those that appeared groundless on intake. Under the change, new charges are assigned to one of three categories. First, charges that fall within the EEOC's national or local enforcement plans, or for which the likelihood seems high that discrimination has occurred, are fully investigated. Second, charges for which evidence of discrimination is insufficient receive further investigation to reclassify them into either the first category (full investigation) or the third category. Under the third category, charges are dismissed if the evidence of discrimination is not compelling or if the charging party or the employer is not covered under the ADA.

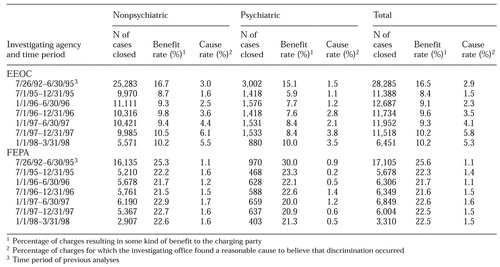

The implementation of new public policies is often problematic, especially at early stages (18,19,20,21). For this reason, we analyzed the data from July 1, 1995, through March 31, 1998, in six-month blocks. As Table 4 shows, after the change in charge processing was implemented, an initial large decrease occurred in the benefit rates of people with psychiatric disabilities whose charges were investigated by the EEOC. The rate fell from 15.1 percent to 5.9 percent. The benefit rate slowly increased to 10 percent in early 1998, but it remained 34 percent lower than the original level.

An initial large decrease—from 16.7 percent to 8.7 percent—was also noted in benefit rates of people with nonpsychiatric disabilities whose charges were investigated by the EEOC. The rate slowly edged up to 10.5 percent in the penultimate period, although it went down in the final period examined. Because benefit rates for charges involving individuals with psychiatric disabilities continued to rise, the gap in benefit rates between individuals with psychiatric disabilities and those with other disabilities disappeared in the final period (10 percent and 10.2 percent, respectively).

For people with psychiatric disabilities whose charges were investigated by a FEPA, an initial large decrease was noted in the benefit rate—from 30 percent to 23.3 percent. Additional decreases followed. Thus, while the benefit rate for FEPA charges involving individuals with psychiatric disabilities was not as low during the final six-month period as it was during the two preceding six -month periods, it was 29 percent lower than it was during the initial time period. For people with other disabilities whose charges were investigated by a FEPA, an initial small decrease in the benefit rate was noted, from 25.3 percent to 22.2 percent. After the decrease, the rate remained stable, between 21.5 percent and 22.9 percent.

Similar to the experience of persons filing with the EEOC, benefit rates for persons with psychiatric disabilities and rates for persons with other disabilities who filed charges with FEPAs moved toward convergence during the period between 1995 and 1998. This finding suggests that the new procedure for handling charges may be bringing about more equivalent results among persons with psychiatric and other disabilities.

Table 4 also compares the rates of findings of reasonable cause during the early and later time periods for people with psychiatric and other disabilities. For persons filing with the EEOC, findings of cause for people with psychiatric disabilities remained consistently lower than such findings for people with other disabilities. However, an increase occurred in findings of cause both for people with psychiatric disabilities and for people with other disabilities whose charges were filed with the EEOC. The initial small decrease for individuals with psychiatric disabilities—from 1.5 percent to 1.1 percent—was followed by an increase to 3.8 percent in the penultimate time period, although the rate decreased slightly in the final time period examined. For people with other disabilities, a similar pattern emerged: an initial decrease, from 3.0 percent to 1.6 percent, led to an increase, 6.1 percent, and then a slight decrease.

Similarly, findings of cause for people with psychiatric disabilities whose charges were investigated by FEPAs were consistently lower than those for people with nonpsychiatric disabilities. However, the percentage of charges resulting in findings of reasonable cause by FEPAs for people with psychiatric disabilities and with other disabilities remained consistently low. For people with psychiatric disabilities, rates ranged from .2 percent to 1.4 percent. For others, rates ranged from 1.1 percent to 1.7 percent.

We also compared the monetary benefits received by individuals with psychiatric and other disabilities during the different time periods, and these results are summarized in Table 5. People with psychiatric disabilities received greater actual monetary benefits than people with other disabilities in almost every time period. For charges investigated by the EEOC, a $4,000 increase between 1992 and 1998 was noted in the median benefit for people with psychiatric disabilities; the increase was almost $3,000 for persons with other disabilities. For charges investigated by FEPAs, little change over time occurred in actual monetary benefits for people with nonpsychiatric disabilities. However, for people with psychiatric disabilities, an increase of $2,250 was found in actual monetary benefits between 1992 and 1998. Moreover, in most of the time periods examined, people with psychiatric disabilities received greater monetary benefits and greater projected monetary benefits than people with other disabilities.

Discussion and conclusions

Our findings deserve careful consideration. Among all Title I charges under ADA, only 15.7 percent resulted in benefits for people who filed them. Whether the charges were investigated by the EEOC or a FEPA, only 1.7 percent of charges resulted in hiring or job reinstatements for people with disabilities. Moreover, the proportion of charges resulting in beneficial outcomes has declined in recent years whether the charges have been investigated by the EEOC or by FEPAs.

The picture may be even grimmer for people with psychiatric disabilities. To be sure, individuals with psychiatric disabilities received greater monetary benefits than individuals with nonpsychiatric disabilities. Furthermore, during the first three years of Title I implementation, individuals with psychiatric disabilities whose charges were investigated by a FEPA had higher rates of benefits than individuals with nonpsychiatric disabilities, and by March 31, 1998, the benefit rates for people with psychiatric disabilities were similar to those of people with nonpsychiatric disabilities. However, throughout the implementation period, individuals with psychiatric disabilities whose charges were investigated by the EEOC had lower benefit rates than individuals with other disabilities. Throughout implementation, individuals with psychiatric disabilities had lower findings of reasonable cause than individuals with other disabilities, regardless of whether a charge was investigated by the EEOC or a FEPA.

In addition, throughout implementation, individuals with schizophrenia, who suffer some of the harshest problems of all people with psychiatric disabilities, had even lower rates of charges resulting in benefits than individuals with other types of psychiatric disabilities. Throughout implementation, individuals with schizophrenia filed very few Title I charges, lending empirical support to those who believe that the ADA probably has less consequence for persons with more severe disorders.

These findings might be interpreted to indicate that the ADA charge process has been ineffective in helping individuals with disabilities find jobs, pursue improved employment opportunities, and better their economic situations. Also, the findings may be taken to support arguments that a large percentage of employment discrimination charges brought under the ADA are frivolous.

For two reasons, we think such negative conclusions are not dictated by our findings. First, sweeping judgments about the success of Title I are premature. Implementation research has found that translating important legislative and administrative policies into action proceeds slowly, requiring years of adjustment, experience, and fine tuning (18,19,20,21). Our data confirm that after only five and a half years of implementation of Title I, more than 2,400 charges resulted in new jobs or reinstatements into old jobs, including 202 charges involving people with psychiatric disabilities. In addition, 22,883 charges resulted in some kind of benefit, including 2,135 charges involving individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Nearly 16,000 charges resulted in monetary benefits, including more than 1,500 charges involving individuals with psychiatric disabilities.

The more important reason for caution in judging the overall success of the Title I enforcement process on the basis of these data is that the data represent an unknown, and probably small, fraction of the total number of instances in which the ADA influences employment decisions. These data do not address compliance without enforcement, the voluntary nondiscriminatory behavior that would best measure the overall success of the ADA (22). The existence of the ADA and the enforcement authority of the EEOC present a powerful stimulus for employers to comply with ADA requirements. The need to respond to a charge, the possibility of investigation, and the chance of being the target of judicial proceedings stimulate many employers who do not initially comply to seek settlements when disputes arise.

In a similar interpretation of findings about consequences of the 1964 Civil Rights Act on female and African-American workers, Blumrosen (18) described how legislation encouraged employers to comply with the values contained in the law. Blumrosen makes an important point: in assessing the impact of equal employment opportunity laws, statistics about charges and cases reveal only the tip of the iceberg. The growing presence of knowledgeable human resource personnel in larger firms has meant that equal-employment laws are implemented without direct government intervention (23). Corporations have adopted policies to inform managers and workers of ADA requirements and enable them to achieve compliance without EEOC intervention. Thus EEOC charge statistics may be disproportionately composed of claims that are factually or legally weak.

Moreover, our data do not indicate that the charge process is failing. The administrative charge process is designed to provide an inexpensive and relatively quick means of resolving disputes between workers and employers. It is easy for a worker who suspects discrimination to file a charge, even if the worker lacks hard evidence to support the claim. There is no fee, no lawyer is required, and charges can be filed by mail or fax. The initial screening of weak or malicious cases, which in standard litigation is performed by lawyers and court clerks, occurs after filing in the ADA charge system.

On the other hand, the data presented here may cause concern about the effectiveness and fairness of the charge process for claimants with meritorious claims. First, there is no means of checking the accuracy of EEOC and FEPA decision making. In addition, individuals whose employment discrimination charges were investigated by both the EEOC and FEPAs during the last several years were less likely to benefit from their charge than those whose charges were investigated during the first three years of implementation. The past several years have seen the courts narrowly interpreting the ADA (24), and the EEOC has changed the procedure for handling charges. Either or both of these factors could have contributed to the decreasing benefit rate.

Given the reduction in the percentages of both EEOC- and FEPA-investigated charges resulting in benefits, it is reasonable to conjecture that as courts have ruled against a growing number of ADA plaintiffs, employers have become less fearful of sanctions and see less reason to settle with complainants. A more probable explanation is that both the court decisions and the EEOC change in charge-handling procedures have contributed to these reductions. The decrease in benefit rates for charges investigated by the EEOC is twice as large as that for charges investigated by FEPAs. Furthermore, although the EEOC plans to pay more attention to settlement and mediation at all stages of processing, it has emphasized reducing the number of charges awaiting resolution and identifying cases that present the most egregious violations (25).

During the last several years, the EEOC has taken decisive action to deal with problems associated with charge processing. It has reduced the time taken to process charges and decreased the inventory of charges awaiting resolution. By focusing investigative resources on stronger cases, the EEOC has increased both the rate of determination of reasonable cause and the monetary benefits received by charging parties. These actions may now allow the EEOC to focus greater attention on settling cases and mediation and on the outcomes of charges investigated by FEPAs.

In summary, our findings suggest some correspondence between the promise of the ADA and actual outcomes. They also support the concept of a federal agency directly and uniformly enforcing a federal law that remains much needed by individuals. In addition, they indicate that outcomes in the administrative charge process have probably been influenced by the trend apparent in the past several years toward narrow interpretation of the ADA by the lower courts. The recent Supreme Court decision in Bragdon v. Abbott (26) took a broad approach to the definition of disability, but the high court is only beginning to clarify the ADA's scope and meaning. After all, it is still early in the life of the ADA.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by grant R01-MH-57077 from the National Institute of Mental Health. They are indebted to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission for arranging the Intergovernmental Personnel Act agreement, which allows the first author access to the EEOC's confidential charge data system. They also thank Donna Curasi for research assistance.

Dr. Moss is a senior research fellow in the School of Social Work and research fellow at the Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 725 Airport Road, Campus Box 7590, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599 (e-mail, [email protected]). Mr. Ullman is social research associate and Ms. Starrett is research associate at the Sheps Center. Mr. Burris is professor of law in the Temple University School of Law in Philadelphia. Dr. Johnsen is research director at ROW Sciences, Inc., in Rockville, Maryland.

|

Table 1. Outcomes of all discrimination charges closed by March 31, 1998, under the Americans With Disabilities Act, by whether the charge was investigated by a field office of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) or by a state or local Fair Employment Practice Agency (FEPA), in percentages

|

Table 2. Outcomes of all discrimination charges by persons reporting psychiatric impairments filed as of March 31, 1998, under the Americans With Disabilities Act, by whether the charge was investigated by a field office of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) or by a state or local Fair Employment Practice Agency (FEPA), by diagnosis and in percentages

|

Table 3. Monetary benefits received by persons filing discrimination charges as of March 31, 1998, under the Americans With Disabilities Act, by whether the charge was investigated by a field office of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) or by a state or local Fair Employment Practice Agency (FEPA)

|

Table 4. Outcomes by six-month periods of all closed discrimination charges by persons reporting psychiatric impairments made through March 31, 1998, under the Americans With Disabilities Act, by whether the charge was investigated by a field office of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) or by a state or local Fair Employment Practice Agency (FEPA)

|

Table 5. Monetary benefits by six-month periods of all discrimination charges closed by March 31, 1998, under the Americans With Disabilities Act, by whether the charge was investigated by a field office of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) or by a state or local Fair Employment Practice Agency (FEPA)

1. Pfeiffer D, Finn J: Survey shows state, territorial, local public officials implementing ADA (Americans With Disabilities Act). Mental and Physical Disability Law Reporter 19:537-540, 1995Google Scholar

2. Blanck PD: Employment integration, economic opportunity, and the Americans With Disabilities Act: empirical study from 1990-1993. Iowa Law Review 79:853-923, 1994Google Scholar

3. Gostin LO, Beyer HA: Implementing the Americans With Disabilities Act: Rights and Responsibilities of All Americans. Baltimore, Brookes, 1993Google Scholar

4. Burgdorf RL Jr: The Americans With Disabilities Act: analysis and implications of a second-generation civil rights statute. Harvard Civil Rights/Civil Liberties Law Review 26:413-522, 1991Google Scholar

5. State and Local Task Force Report. Washington, DC, Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 1995Google Scholar

6. Estroff SE, Zinuner C, Lachicotte WS, et al: "No other way to go": pathways to disability income application among persons with severe persistent mental illness, in Mental Disorder, Work Disability, and the Law. Edited by Bonnie R, Monahan J. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1997Google Scholar

7. Psychiatric Disabilities, Employment, and the Americans With Disabilities Act. Washington, DC, Office of Technology Assessment, 1994Google Scholar

8. Link B: Mental patient status, work, and income: an examination of the effects of psychiatric labels. American Sociological Review 47:202-215, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Black B: Work and Mental Illness: Transitions to Employment. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988Google Scholar

10. Moss K, Ullman M, Johnsen M, et al: Different paths to justice: the ADA, employment, and administrative enforcement by the EEOC and FEPAs. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 17:29-46, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Moss K, Johnsen M, Ullman M: Assessing employment discrimination charges filed by individuals with psychiatric disabilities under the Americans With Disabilities Act. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 9:81-105, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Moss K, Johnsen M: Employment discrimination and the ADA: a study of the administrative complaint process. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 21(2):111-121, 1997Google Scholar

13. Moss K: The ADA employment discrimination charge process: how does it work and who is it benefiting? in Employment, Disability, and the Americans With Disabilities Act: Issues in Law, Public Policy, and Research. Edited by Blanck PD. Chicago, Northwestern University Press, in pressGoogle Scholar

14. EEOC's Expanding Workload, Increases in Age Discrimination and Other Charges Call for New Approach. Report no HEHS-94-32. Washington, DC, US General Accounting Office, 1994Google Scholar

15. Selmi M: The value of the EEOC: reexamining the agency's role in employment discrimination law. Ohio State Law Journal 57:1-64, 1996Google Scholar

16. Seymour RT: Excerpts from the Lawyers' Committee's Dec 19, 1992, recommendations to the Clinton transition team (footnotes omitted). Civil Rights Act and EEOC News, May 8, 1995, p 2Google Scholar

17. Oversight Hearing on the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Select Education and Civil Rights of the House Committee on Education and Labor. 103rd Congress, 2nd Session. Testimony of AW Blumrosen, 1994Google Scholar

18. Blumrosen AW: Modern law: The Law Transmission System and Equal Employment Opportunity. Madison, Wisc, University of Wisconsin Press, 1993Google Scholar

19. Percy SL: Disability, Civil Rights, and Public Policy: The Politics of Implementation. Tuscaloosa, Ala, University of Alabama Press, 1989Google Scholar

20. Wilson JQ: Bureaucracy: What Government Agencies Do and Why They Do It. New York, Basic Books, 1989Google Scholar

21. Goldman HH, Morrissey JP, Ridgely MS, et al: Lessons from the program on chronic mental illness. Health Affairs 11(3):51-68, 1992Google Scholar

22. Burris S, Moss K: A road map for ADA Title I research, in Employment, Disability, and the Americans With Disabilities Act: Issues in Law, Public Policy, and Research. Edited by Blanck PD. Chicago, Northwestern University Press, in pressGoogle Scholar

23. Edelman LB: Legal ambiguity and symbolic structures: organizational mediation of civil rights law. American Journal of Sociology 97:1531-1576, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Burgdorf R Jr: "Substantially limited" protection from disability discrimination: the special treatment model and misconceptions of the definition of disability. Villanova Law Review 42:409-585, 1997Google Scholar

25. Igasaki PM, Miller PS: Priority Charge Handling Task Force and Litigation Task Force Report, March 1998. Available at www.eeoc.gov/task/pchlit-1.htmlGoogle Scholar

26. Bragdon v Abbott, 118 S Ct 540 (1998)Google Scholar