Lessons From the First Two Years of Project Heartland, Oklahoma's Mental Health Response to the 1995 Bombing

Abstract

On April 19, 1995, a terrorist bombing in Oklahoma City killed 168 people and injured 853 others. The Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services was the lead agency in crafting a community mental health response to reduce impairment of those affected. The Project Heartland program, which opened on May 15, 1995, was the first community mental health program in the U.S. designed to intervene in the short to medium term with survivors of a major terrorist event. The authors describe lessons learned in the areas of planning and service delivery, as well as the types and extent of services provided in the project's first two years.

At 9:02 a.m. on April 19, 1995, a yellow rental truck containing a bomb exploded in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City. This major disaster resulted in the deaths of 168 people; 853 were injured.

On May 15, 1995, the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (ODMHSAS) opened Project Heartland, America's first community mental health program specifically designed to intervene in the short to medium term with the survivors of a major terrorist event. This paper describes Project Heartland's first two years of operation.

Project Heartland

The disaster model

The Oklahoma City bombing was a human-made, centripetal disaster (1) in which victims lived or worked in the affected area and the entire community shared in the assault. Such disasters tax local resources but also unite residents in the recovery process.

Project Heartland was established with funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) through the Center for Mental Health Services. Its design, implementation, and management is solely a local effort, although federal guidelines dictate service priorities. Current funding is through the Office for Victims of Crime of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Disasters can be viewed in phases (2,3,4,5). Project Heartland staff used the model described by Farberow and Frederick (4) and Myers (6) because it is consistent with the federal response in structure and process. These authors describe a four-phase paradigm. The phases are called the heroic phase, the honeymoon phase, the disillusionment phase, and the reconstruction phase. The model provided Project Heartland staff with a framework for understanding and preparing to meet the public's needs over time.

Planning

The goal of Project Heartland was—and continues to be—to provide crisis counseling, support groups, outreach, and education for individuals affected by the bombing. Several concerns became evident in the first days after the bombing. ODMHSAS, the state agency selected to organize, coordinate, and conduct the mental health response, had no disaster plan in place. Furthermore, the Oklahoma Office of Civil Emergency Management had little previous interaction with ODMHSAS, and no interagency service agreement existed. Despite the lack of a formal agreement, work commenced, and by April 24 planning began.

The American Red Cross provides only immediate postimpact crisis services. The Compassion Center, the support and death-notification program established by the Red Cross in downtown Oklahoma City, closed within ten days. Unfortunately, tension among individuals and organizations involved in disaster response is not unusual. After the bombing, staff of the local Red Cross did not wish to transfer responsibility to Project Heartland as directed, and they resisted training ODMHSAS staff.

To decrease the likelihood of such conflicts over leadership during transitions and to provide consistency in leadership, it is prudent that the postimpact counseling and death-notification center be directed by specially trained staff from the state agency responsible for developing and maintaining the postdisaster plan. This staff should work closely with other agencies in predisaster planning and disaster response and should be knowledgeable about the various organizations involved in the response. This staff needs clear governmental authority to direct service delivery.

In May 1995 ODMHSAS sponsored a statewide forum in Oklahoma City to obtain community input in the development of service goals for the mental health recovery plan. This use of a quasipublic disaster relief planning workshop appears unique in the disaster literature. One-hundred stakeholders were invited to participate in one of five half-day facilitated workshops to develop specific mental health goals for disaster recovery.

The stakeholders made 15 primary recommendations to help ensure that the agencies involved in Project Heartland would enlist qualified providers and use a multidisciplinary team approach to deliver accessible, high-quality, culturally sensitive services to a variety of special populations affected by the bombing. The recommendations also focused on ensuring that the media would be educated about responses to trauma and that the needs of rescue workers, those already affected by mental illness, the homeless, and civilian workers in the area would not be overlooked. The needs of children were a special concern, and a companion paper addresses Project Heartland's services for children (7).

Implementing services

Project Heartland is located in a two-story multitenant office building within easy reach of public transportation. The project was initially staffed with 22 individuals, including a director, professional counselors, outreach workers, and support personnel. It became clear that it was a mistake to hire younger individuals, many of whom had no experience dealing with death or related issues. It is strongly recommended that each state's mental health department have a cadre of culturally sensitive and mature individuals trained in critical-incident stress debriefing and other interventions.

Vicarious traumatization was a problem, and exposure to the traumatic experiences and rage of survivors caused erosion of staff morale. This erosion became evident in physical illness and emotional distress and in increasing absenteeism rates. A psychologist with training in disaster mental health was employed to debrief and support staff and to provide clinical case review. We recommend that the consultant who provides support to staff should not also provide case consultation because the consultant's critical review of a therapist's work may discourage the therapist from openly sharing personal reactions.

Project Heartland contracted with eight partners—both state and private organizations—to extend services to predefined populations, including ethnic minorities, persons with preexisting emotional disorders, elderly persons, and children. We believe that this blend of state and private groups is both unique and highly desirable because it offers accessible services by experienced professionals and integrates postdisaster services with existing programs.

Subcontractors were functionally independent of Project Heartland. We recommend that other disaster response programs use the contract itself to address potential problems. For example, the contract should specify the amount of time to be spent in direct clinical service and expressly require all subcontracted clinicians to have at least a master's degree, to be licensed or licensable in a mental health profession, and to participate in ongoing training in areas such as outreach, evaluation and referral, crisis and grief counseling, and record keeping.

Services

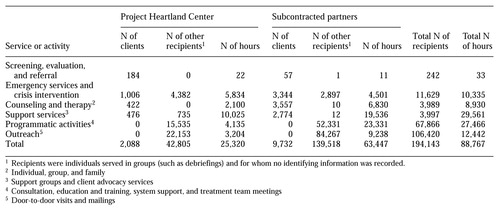

As Table 1 shows, in the first two years of Project Heartland, the greatest number of service hours were spent providing support services, which include support groups and client advocacy services. Providing programmatic activities accounted for the next largest number of hours; they included consultation, education and training, system support, and treatment team meetings. Following these services in number of hours were outreach services, which included door-to-door visits and mailings; emergency services and crisis intervention; counseling and therapy; and screening, evaluation, and referral services.

Crisis intervention and individual counseling.

Project Heartland staff provided crisis counseling person-to-person at the center, at clients' homes and workplaces, and by a telephone hotline. Crisis services typically centered on suicide threats, family violence, and workplace conflict.

Evaluation and referral.

Project Heartland was not intended to serve those with serious emotional problems or to provide comprehensive psychological assessments. Policies were developed to refer those in need of more intensive intervention. Nevertheless, Project Heartland was criticized by some professionals because of a perceived failure to refer individuals in need of more traditional and intensive services. It is recommended that each state's mental health authority establish service agreements with mental health professional and licensure organizations that detail collaborative efforts during and after a disaster.

Support groups.

Twenty-one separate support groups were established in the first two years after the bombing. They consisted of groups for survivors, parents who lost young children, parents who lost adult children, adult siblings of victims, widows and widowers, state employees directly affected, downtown workers and residents, rescuers and responders, school personnel, displaced persons, employee groups with multiple losses, and homeless persons who were in the downtown area during the bombing.

Groups were constituted on the basis of suggestions of individuals responding to outreach efforts. Group attendance and duration varied, but all were considered successful. Flexibility is recommended in deciding what kinds of groups to offer, adapting to the changing needs and interests of potential participants.

Outreach.

The maximum impact of outreach efforts occurred in the first 12 months. Outreach was accomplished in several ways. The outreach staff visited every home and business within a mile radius of the blast. Home visits were also made to survivors, victim's families, and rescue workers. They stationed staff at the FEMA disaster center and the American Red Cross Center as long as those facilities were open. They attended meetings and reunions of survivor groups.

In addition, outreach staff held two intensive retreats with persons who were directly affected by the bombing. They assisted apartment dwellers returning to buildings in downtown locations that had been evacuated for months. Outreach staff regularly correspond with survivors and survivors' families about new programs, events, and projects. Material about traumatic bereavement was mailed to victim's families and injured survivors. In retrospect, it would have been preferable to have more outreach staff for a shorter period of time, especially during the first six months. It is recommended that outreach training be included in the predisaster planning effort.

Consultation, education, and the media.

In the two-year period after the bombing, Project Heartland provided disaster-related education and training to more than 10,500 people. Topics included posttraumatic stress disorder, traumatic bereavement, children and disasters, the role of the media in recovery, and school-based services. It is recommended that a media policy and a formal media liaison be implemented and utilized immediately after a disaster.

Conclusions

During Project Heartland's first two years of existence, staff were creative and flexible in researching, designing, and implementing services for survivors, family members, and the community. Staff members studied the literature, consulted with experienced colleagues, and routinely examined the program's mission and goals. They continue to provide services although the program is reduced in size and focus.

Unfortunately, one of the program's shortcomings has been a failure to systematically and contemporaneously evaluate its effectiveness. Therefore, the lessons learned in the process are anecdotal. Nevertheless, they should be studied by those involved in developing services in anticipation of future terrorist attacks in other American cities.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the following individuals who provided information essential to this report: Gwen Allen, M.S.W., M.P.H., K. Lynn Anderson, J.D., Sharron D. Boehler, M.N., M.B.A., Brian W. Flynn, Ed.D., Mary Elizabeth "Tipper" Gore, and N. Ann Lowrance, M.S.

Dr. Call is in the private practice of forensic and clinical psychology and, along with Dr. Pfefferbaum, is a member of the board of the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services. Dr. Pfefferbaum also is professor and chairman of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the College of Medicine at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, 920 S. L. Young Boulevard, Williams Pavilion, No. 3470, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73104 (e-mail, [email protected]). Send correspondence to Dr. Pfefferbaum.

|

Table 1. Services and activities of Project Heartland and its subcontracted partner organizations in the first two years after the Oklahoma City terrorist bombing in April 1995

1. Lindy JD, Grace MC, Green BL: Survivors: outreach to a reluctant population. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 51:468-478, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Aptekar L: A comparison of the bicoastal disasters of 1989. Behavior Science Research 24:73-104, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Farberow NL: Mental health aspects of disaster in smaller communities. American Journal of Social Psychiatry 4:43-55, 1985Google Scholar

4. Farberow NL, Frederick CJ: Training Manual for Human Service Workers in Major Disasters. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1996Google Scholar

5. Lechat MF: The public health dimensions of disasters. International Journal of Mental Health 19:70-79, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Myers D: Disaster Response and Recovery: A Handbook for Mental Health Professionals. DHHS publication (SMA) 94-3010. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1994Google Scholar

7. Pfefferbaum B, Call JA, Sconzo GM: Mental health services for children in the first two years after the 1995 Oklahoma City terrorist bombing. Psychiatric Services 50:956-958, 999Google Scholar