Termination of Social Security Benefits Among Los Angeles Recipients Disabled by Substance Abuse

Abstract

Objectives: Although a 1996 federal law terminated Social Security disability benefits to individuals disabled primarily by drug addiction and alcoholism, many were expected to successfully appeal for recertification based on mental illness. This study examined appeal and recertification in Los Angeles County. METHODS: Data for 2,001 persons receiving Social Security disability benefits in 1996 because of substance abuse disability were obtained from the referral and monitoring agency, where each person had completed the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) during an initial visit in the past two years. Administrative data were obtained from the Social Security Administration. Severity of psychiatric symptoms—low, medium, or high—was based on the composite score on the ASI psychiatric subscale. Logistic regression analyses examined the relationship between severity and appeal and recertification status. RESULTS: Fifty-one percent of the subjects scored in the medium- or high-severity range. Appeals were made by 80 percent of the 506 recipients with high scores, 72 percent of the 510 recipients with medium scores, and 74 percent of the 985 recipients with low scores. Recertification rates were 60 percent, 45 percent, and 47 percent, respectively. Compared with recipients who had low scores, those with high scores were more likely to appeal and to be recertified. However, benefits were terminated for 51 percent of recipients with high scores, including all those who did not appeal. CONCLUSIONS: Many recipients of Social Security disability benefits with comorbid psychiatric problems lost benefits either because they did not appeal or because their appeal was denied.

In March 1996 Congress passed Public Law 104-121, which terminated Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) to individuals disabled primarily by drug addiction or alcoholism. The law eliminated substance abuse as a basis for granting benefits under the SSI and SSDI programs. Beneficiaries lost monthly cash payments and health insurance coverage from Medicaid, through SSI, and Medicare, through SSDI. In addition, they were no longer required to be in substance abuse treatment or have a payee to manage their funds.

Individuals were notified in June 1996 that their benefits would be terminated on January 1, 1997, unless they applied for recertification under another disability status. The Social Security Administration estimated that three-quarters of those scheduled to have benefits terminated would qualify for recertification, primarily under a mental health disability (Funk N, Social Security Administration, personal communication, October 1996). However, nationally only 67 percent of those scheduled for benefit termination appealed for recertification, and only half were successful. Thus, benefits were terminated for 69 percent of those scheduled for termination (1).

The lower-than-expected appeal and recertification rates raise the question of whether persons with comorbid mental illness were able to successfully negotiate the recertification process. Because of the high costs of their care (2,3), persons with dual diagnoses are often vulnerable to disruptions in care, which is of particular concern to policy makers.

Using data from Los Angeles County, we analyzed the relationship between self-reported psychiatric problems and recertification and tested two competing hypotheses. The first hypothesis is that individuals with comorbid psychiatric problems are more likely than other substance abusers to be in treatment programs (4) and therefore would have higher rates of recertification because program personnel would assist them with the process. An alternative hypothesis draws on past evidence that individuals with a dual diagnosis have great difficulty negotiating bureaucracies and thus would be less likely to be successful in gaining recertification, even if they were in treatment.

Methods

Subjects

In 1994 Congress mandated that recipients of Social Security disability benefits who had drug addiction or alcoholism must participate in treatment to receive benefits. The referral and monitoring agency was set up to refer beneficiaries and monitor treatment attendance. At the time of initial referral to the agency, individuals completed the fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (5).

Data from these agencies, including ASI scores, for all monitored individuals in California were merged with data from the Social Security Administration on recertification status for Los Angeles County beneficiaries in 1996 (N=6,304), generating 2,001 unduplicated matches. The mean±SD age of subjects was 45.8± 9.4 years. Seventy-three percent of the subjects were male. Fifty-five percent of the subjects were African American, and 26 percent were white.

We compared selected characteristics of the 2,001 monitored beneficiaries with the population of beneficiaries in Los Angeles. The monitored group had a higher rate of appeal for recertification than the larger population of beneficiaries (75 percent versus 66 percent). However, rates of recertification were similar for both groups (48 percent and 50 percent, respectively). Other demographic and socioeconomic characteristics were also similar.

Data from the referral and monitoring agencies indicated that monitored individuals reported high levels of mental health service use and psychiatric symptoms. Thirty-eight percent had been hospitalized at least once, and 68 percent reported psychiatric problems in the past month. Substance use was relatively uncommon. Fifty percent reported no alcohol use in the 30 days before the ASI was administered. Less than 10 percent reported any other drug use in the preceding 30 days except for cocaine, which was reported by 18 percent.

Health status measures

The ASI was designed to evaluate severity of addiction, including the severity of medical problems and psychiatric symptoms. It is a widely used, well-validated, and reliable instrument for research involving substance-using populations (6). However, recent studies question its reliability and validity among people with both a substance use disorder and a severe mental illness such as schizophrenia (7,8). Persons with severe mental illness may misunderstand or confuse questions or may not answer questions, leading to problems with missing data. In addition, among people with severe mental illness a ceiling effect has been observed for questions about mental health; subjects tend to endorse each symptom at the highest level (7,8).

Despite these limitations, the ASI is the only measure that was used to assess the mental health characteristics of this population. Composite severity scores have been mathematically derived from the index and have been shown to be reliable and valid measures of problem severity (9).

The composite score for the psychiatric subscale of the ASI is a weighted combination of 11 questions. Seven questions measure psychiatric symptoms during the past 30 days, one question measures use of prescribed psychotropic medication, and three questions assess the frequency of psychiatric symptoms and the individual's perceived need for treatment. Composite scores range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating greater problems. Using the psychiatric composite score, we characterized the psychiatric severity of individuals as low (a score of .3 or less), medium (higher than .3 and less than .7), or high (a score of .7 or higher), and we described the clinical characteristics of the three groups.

Analyses

Logistic regression was used to predict whether subjects would appeal for recertification and whether they would be successful. We hypothesized that appeal and recertification might be influenced by factors other than mental illness, including demographic characteristics, severity of medical illness, and social support. In addition, because the ASI was administered up to two years before the appeal process, we created a measure of time since ASI assessment. The models described do not include measures of social support or length of time since assessment, because these variables were not significantly related to either appeal or recertification.

Results

When the 2,001 subjects completed the ASI, many reported using mental health services, and more than half reported current psychiatric symptoms. Thirty-eight percent of the sample reported previous psychiatric hospitalizations, 44 percent reported previous use of outpatient psychiatric services, and 45 percent reported having at some time experienced hallucinations. Most individuals did not report significant drug or alcohol problems in the past 30 days. The scores of 72 percent were in the lowest third of the alcohol composite score, and the scores of 95 percent were in the lowest third of the drug use composite score.

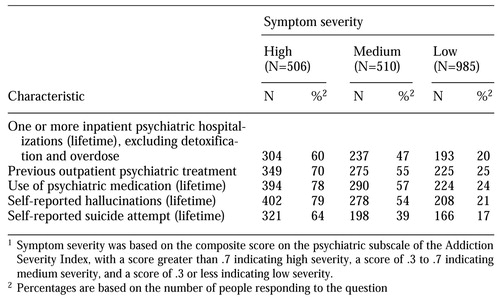

Table 1 presents information on clinical characteristics of subjects with symptoms of high, medium, and low severity. Most individuals scored low in psychiatric severity (N=985), and the numbers scoring medium and high were similar (510 and 506 subjects, respectively).

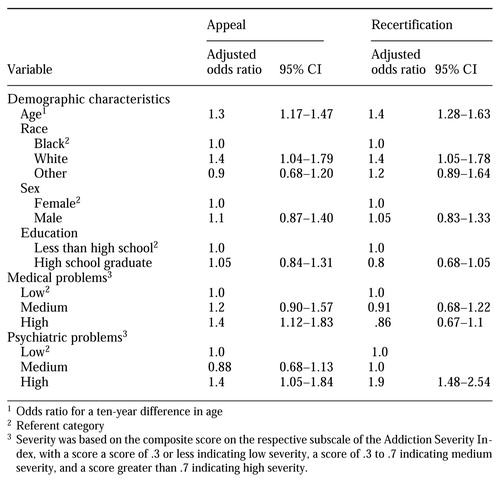

Table 2 shows the results of the logistic regression for both appeal and recertification. In both analyses, a psychiatric severity score in the high range was associated with a higher adjusted odds ratios of appealing (odds ratio [OR]=1.4, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.05 to 1.8) and of being recertified (OR=1.9, CI=1.5 to 2.5). Other significant positive predictors of appeal were age, race, and severity of medical illness; older recipients, white recipients, and those with severe medical problems were more likely to appeal. Age and race also predicted recertification; older recipients and white recipients were more likely to be recertified.

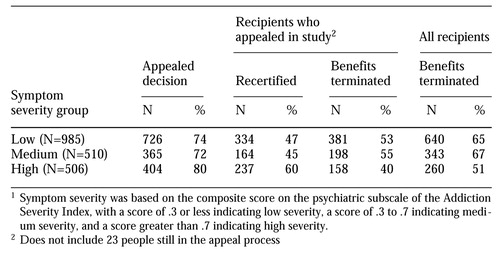

Table 3 shows the relationship between psychiatric severity and appeal and recertification. Although patients with high-severity psychiatric symptoms were more likely to appeal and to be recertified than those with medium- and low-severity symptoms, the benefits of 51 percent of those who reported high-severity psychiatric symptoms were terminated, including all those who did not appeal. Twenty percent of individuals with high psychiatric severity scores did not appeal, and 40 percent of those who did appeal were denied.

Discussion

When SSI and SSDI were terminated for individuals disabled primarily by drug addiction and alcoholism, successful appeals for recertification nationwide were substantially lower than anticipated. Our study in Los Angeles County shows that although persons with more severe psychiatric symptoms were significantly more likely to appeal and to be recertified than persons with less severe symptoms, many individuals who reported significant psychiatric problems either did not appeal or were unsuccessful.

We do not know the relationship between psychiatric severity as measured by the ASI and the Social Security Administration's thresholds for disability. Thus we cannot determine whether the Social Security Administration appropriately applied its criteria or if its criteria miss many persons with severe illness. However, it is of concern that many individuals with self-reported psychiatric problems appear to have lost both income support and health insurance. The benefits of more than half of those who were characterized in this study as having severe problems were terminated.

Our results are based on the census of individuals who were seen at least once by the California referral and monitoring agency. The agency was mandated to monitor all individuals receiving SSDI or SSI for a substance abuse disability. Between 1994 and 1996 the agency monitored 18,000 of the 43,000 individuals who received benefits because of a disability resulting primarily from drug addiction and alcoholism. Some of the people not monitored may have been in ongoing treatment and thus not in need of a referral. Some may have been highly resistant to treatment. Unfortunately, no clinical information is available for individuals who were not monitored.

Despite the likely heterogeneity of those who were not monitored, comparisons between monitored beneficiaries and all beneficiaries in Los Angeles suggest that the two groups were similar. Although the monitored beneficiaries had a higher rate of appeals, they were similar to other recipients in work history, indigence, age, and recertification. Although lack of data on the unmonitored group limits interpretation of the results, the monitored group represented nearly a third of all persons in Los Angeles who received Social Security disability benefits in 1996 due to a disability resulting from drug addiction or alcoholism. As of December 1996, overall 20 percent of persons who receive disability benefits for these reasons live in California—15 percent in Los Angeles (Social Security Administration, Regional Public Affairs Office, San Francisco, personal communication, 1997).

Additional limitations of our study should be noted. Often studies that use administrative records as data sources must make do with imperfect measures. This study is no exception. The ASI uses self-reported measures of psychiatric symptoms and problem severity. Individuals may report symptoms but may not be mentally ill, although this situation is not common (10). Typically, substance abuse is associated with transient psychiatric symptoms that resolve quickly with sobriety. However, given the low levels of current drug and alcohol use reported by this group, it is likely that most mental health problems were not secondary to current substance abuse.

In addition, the ASI was administered when a recipient established contact with the referral and monitoring agency, and it was not readministered. Mental illness and psychiatric impairment can fluctuate with time, and because of the length of the study (June 1994 through December 1996), our measures may not have reflected subjects' current psychiatric status. Unfortunately, no other information is available on the nature of the psychiatric problems reported.

Another limitation concerns the reliability and validity of the ASI among subjects who have both a severe and persistent mental illness and a substance use disorder. Severely mentally ill patients may misunderstand questions (8), and one study of the ASI in a sample composed primarily of people with schizophrenia showed low test-retest reliability (7). At the same time, the great majority of our subjects were not as severely ill as those evaluated in the earlier studies, who were all legally incompetent. In fact, interviewer codes are given in each section of the ASI so that the interviewer can note whether the information collected was compromised by the patient's inability to understand, concentrate, or report accurately. Less than 2 percent of these items were checked, suggesting that the vast majority of the subjects in our study understood the questions.

Another limitation concerns the interpretation of our results. Our data on recertification are from March 1997. People whose appeal was denied may have appealed the denial and may have been recertified later. Thus the results reported here are for a point in time only and are a snapshot of a dynamic process.

Conclusions

Our study has several policy and public health implications. First, after the law was passed, fewer people remained eligible for SSI and SSDI, which reduced federal expenditures. Second, although psychiatric severity predicted both appeal and recertification, many of those who lost benefits had significant self-reported psychiatric problems in the absence of active substance abuse. We are not equating our measures of psychiatric severity with the federal definition of psychiatric disability used to determine entitlement support. However, the clinical measures that were the basis for the psychiatric severity score in our study suggest that some people with significant mental health problems lost benefits, raising concern for their welfare.

Some individuals may continue to need health services, and, without federal income support and health insurance, states and local communities may feel pressure to assume the costs of their care. Thus the legislation to end benefits to this group may result in cost shifting from the federal government to state and local governments, rather than cost saving.

Practitioners and policy makers can take several steps to address the potential consequences of the legislation. Practitioners who treat formerly eligible recipients of SSDI and SSI can assess whether the individual might continue to be eligible for benefits and assist the individual in the application process. Policy makers can mandate representative payees for dually diagnosed individuals. Finally, longer-term research on social and health outcomes for this population is needed to assess the ultimate effects of the legislation on these individuals and on the communities in which they reside.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant 029036 from the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and the VA West Los Angeles to Dr. Watkins; by the UCLA department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences to Drs. Watkins and Wells; and by grant MH-54623 from the Research Center on Managed Care for Psychiatric Disorders at the National Institute of Mental Health to Drs. Watkins and Wells.

Dr. Watkins is a research psychiatrist at Rand, 1700 Main Street, Santa Monica, California 90407-2138 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Wells is professor of psychiatry in the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral science at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. McLellan is professor of psychiatry in the department of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the National Institute of Mental Health conference on "Improving the Condition of People With Mental Illness: The Role of Services Research" held September 4-5, 1997, in Washington D.C.

|

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of 2,001 recipients of Social Security disability benefits in Los Angeles County who received benefits because of a disability resulting from drug addiction or alcohol, by whether they reported psychiatric symptoms of high, medium, or low severity

|

Table 2. Results of logistic regression of factors predicting whether a person whose Social Security disability benefits were threatened with termination would appeal and would be recertified

|

Table 3. Appeal, recertification, and termination of benefits among 2,001 recipients of Social Security disability benefits in Los Angeles County, by whether they reported psychiatric symptoms of high, medium, or low severity

1. Highlights of Summary Report of Drug Addiction and Alcoholism Implementation. Washington, DC, Social Security Administration, 1997Google Scholar

2. Bartels SJ, Teague GB, Drake RE, et al: Substance abuse in schizophrenia: service utilization and costs. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:227-232, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Dickey B, Azeni H: Persons with dual diagnoses of substance abuse and major mental illness: their excess costs of psychiatric care. American Journal of Public Health 86:973-977, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. JAMA 264:2511-2518, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al: The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 9:199-213, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Caccioa J: New data from the Addiction Severity Index: reliability and validity in three centers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26-33, 1985Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Corse SJ, Hirschinger NB, Zanis D: The use of the Addiction Severity Index with people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 19(1):9-18, 1995Google Scholar

8. Zanis DA, McLellan TA, Corse S: Is the Addiction Severity Index a reliable and valid assessment instrument among clients with severe and persistent mental illness and substance abuse disorders? Community Mental Health Journal 33:213-227, 1997Google Scholar

9. Alterman AI, Brown L, Zaballero A, et al: The interviewer severity ratings and composite scores of the ASI: a further look. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 34:201-209, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

10. McLellan AT, Cacciola J, Kushner H, et al: The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index: cautions, additions, and normative data. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 9:461-480, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar