Predicting Outcome of Inpatient Detoxification of Substance Abusers

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Variables that have been identified as predictors of outcome of substance abuse treatment— coping style, addiction severity and addiction-related problems, psychopathology, and treatment motivation— were examined as predictors of outcome of inpatient detoxification. METHODS: A cohort of 175 drug abuse patients consecutively admitted to an inpatient detoxification clinic in the Netherlands were assessed. Baseline data were obtained on psychopathology using the Symptom Checklist-90, on severity and addiction-related problems using the Addiction Severity Index (ASI), on personal coping style using the Utrecht Coping List, on motivation using the CMRS scales, and on sociodemographic background. Positive detoxification outcome was defined as transfer to inpatient rehabilitation treatment. RESULTS: Of the 175 admissions, 81 (46 percent) had a positive outcome, and 94 (54 percent) had a negative outcome. Severe drug use and severe medical problems, as measured by the ASI, were the best predictors of a negative outcome of detoxification. Self-rated suitability of postdetoxification treatment was also a predictor of positive outcome, although to a lesser degree than the ASI variables. Established predictors of residential drug abuse treatment outcome, such as psychopathology, coping style, and sociodemographic variables, did not predict outcome of detoxification. CONCLUSIONS: Caution is necessary when applying results of inpatient treatment outcome studies to inpatient detoxification programs. Different factors may play a role in the outcome of detoxification. To improve the rate at which patients in detoxification programs are transferred to longer-term rehabilitation, more attention should be paid to medical conditions and to the direct consequences of drug use, such as withdrawal symptoms and craving during detoxification.

Generally, detoxification programs are the first step in inpatient substance abuse treatment programs. However, these programs are rarely effective by themselves. Individuals usually need further treatment, such as in a rehabilitation program, to maintain abstinence or establish a prolonged reduction in substance use.

Although a negative outcome for patients in detoxification programs is common (1,2), such an outcome is not limited to detoxification programs. In the field of substance abuse treatment, and mental health care in general, noncompletion of treatment is a general problem. Approximately 50 percent of the patients in substance abuse treatment do not complete the first month of treatment (2). Treatment noncompletion is generally associated with poor success and an unfavorable long-term outcome (3). Therefore, improving a treatment program's "holding power" may be an important starting point for improving outcomes of patients in substance abuse programs.

Factors that influence treatment outcome during the detoxification stage are still poorly understood. Predictors of outcome for patients in substance abuse treatment programs include motivation for treatment (4); psychopathology (5,6); addiction-related problems such as family-social, medical, and legal problems (6); and coping styles (7,8). However, many detoxification studies examine only sociodemographic variables, and few use structured interviews and standardized tests (1,9). In addition, in studies on detoxification outcome, the operationalization of outcome is often subject to debate. Outcome measures used in previous studies include completion of the program, transfer to further treatment, abstinence, and admission to other detoxification programs (9).

This prospective cohort study examined known predictors of long-term treatment outcome as predictors of detoxification outcome. The predictors examined were coping style, addiction severity, addiction-related problems, psychopathology, and treatment motivation. The study was conducted in a detoxification unit in an inpatient drug abuse treatment setting. The detoxification unit does not have a fixed length of stay, and the unit's major treatment goal is transfer of patients to prolonged treatment. Thus positive outcome was defined as transfer from the detoxification unit to prolonged treatment (9).

Methods

Setting

The detoxification unit is part of a large inpatient addiction treatment center of the Parnassia psychiatric hospital in the Hague, the Netherlands. The unit serves both as an opiate detoxification clinic and as a mode of entry to long-term residential care for patients in treatment for opiate addiction and for other substances. The detoxification regimen for opiate-dependent patients consists of a gradual methadone reduction schedule, supported if necessary by additional medication such as benzodiazepines. Depending on the patient's opiate use before admission, the opiate detoxification period generally lasts from seven to 21 days.

After admission, both opiate-dependent patents and those dependent on other substances participate in a variety of structured activities, including group therapy sessions, motivational and educational seminars, and various physical activities, which patients continue to attend after they complete the methadone reduction regimen. On average, patients stay in the unit for 14 to 28 days.

Instruments

To assess addiction severity and addiction-related problems, the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (10,11) was used. The ASI is a semistructured interview that collects data in seven problem areas: medical problems, employment problems, alcohol use, drug use, criminality, family and social problems, and psychiatric problems. In addition, the ASI was used to obtain information about patients' sociodemographic characteristics and drug abuse background. The ASI has satisfactory psychometric properties, with reasonable to good reliability and reasonable validity (11).

For assessment of psychopathology, the Dutch version of the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) was used. The SCL-90 consists of 90 items addressing eight areas of psychopathology: depression, anxiety, agoraphobia, somatization, interpersonal sensitivity and paranoid ideation, hostility, cognitive performance difficulties, and sleep disturbance (12). The SCL-90 is a valid and reliable indicator of psychopathology (13).

The Utrecht Coping List (UCL) (14) was used to differentiate coping styles in the sample. Consisting of seven subscales, with 47 items, that represent different coping styles in problem situations, the UCL is based on the classification developed by Westbrook (15). The different styles include active problem solving, which involves confronting problems and employing purposeful strategies, and palliative reaction, which entails distracting one's attention from the problems and includes smoking and drinking. A third coping style is avoidance, characterized by waiting and keeping clear of the problem. Socialization is a style that entails seeking comfort and help from others, and passive reaction involves rumination and drawing back. The final two coping styles assessed by the UCL are expression of emotions, such as anger or annoyance, and reassuring thoughts, or self-encouragement through such thoughts as "worse things can happen." In a Dutch population, the UCL has been found to have satisfactory psychometric properties (16), with alphas ranging from .64 to .82 and an adequate factorial structure.

The CMRS questionnaire (17) was used to assess motivational aspects of admission to treatment. The CMRS questionnaire examines motivation in four areas: circumstances, or external conditions that influence people to seek treatment; internal motivation, or an individual's inner reasons to change; readiness, or the person's perceived need for treatment; and suitability for treatment. Five subscales measure suitability for detoxification only, for long-term treatment, for short-term treatment, for methadone treatment, and for ambulatory treatment. All CMRS subscales examine the individual's perception of the suitability of the treatment modality.

In an American population, the CMRS questionnaire was found to have satisfactory psychometric properties (17). Because no Dutch version of the CMRS was available, the instrument was translated into Dutch. Psychometric properties of the Dutch instrument are unknown.

Subjects and procedure

A cohort of 175 patients consecutively admitted to the detoxification unit between September 1996 and December 1997 was investigated. Baseline assessments, including the ASI, SCL-90, and UCL, were administered in an outpatient unit before patients entered the detoxification unit. During the first day of admission to the detoxification unit, the CMRS questionnaire was administered. Dropout from treatment was registered by the treatment staff.

Twenty-seven of the subjects (15 percent) were female. The mean±SD age of the subjects was 29.8±7.1 years (range, 17 to 47 years). A small proportion of the sample was married (eight patients, or 5 percent). Fifty-one patients (29 percent) lived alone. The ethnic background of the subjects was mainly white European 142 patients, or 82 percent).

A total of 129 patients (74 percent) attended high school, and 34 (19 percent) attended college. Ten patients (6 percent) had only a primary education, and two (1 percent) had no education. The mean±SD years of education was 10.7±2.2 years.

For the 130 patients in treatment for heroin addiction, the mean±SD age for first regular heroin use, which was measured as use at least three days a week, was 20.3±5.5 years (range, ten to 45 years). The mean± SD years for regular heroin use, which excluded the number of years abstinent, was 5.7±5.5. Forty-five patients (26 percent of the sample) had never used heroin more than three days a week.

For the 145 patients who used cocaine, the mean±SD age of first regular cocaine use, which was measured as use at least three days a week, was 20.9±5.4 years (range, 13 to 39 years). The mean±SD years of regular cocaine use was 5.0±4. Thirty patients (17 percent of the sample) had never used cocaine more than three days a week.

The primary substance of use was heroin for 99 patients (57 percent), cocaine for 41 (23 percent), methadone for nine (5 percent), amphetamine for nine (5 percent), and other substances (benzodiazepines, alcohol, and cannabis) for 17 (10 percent). The majority of patients (168 patients, or 96 percent) were polydrug users.

A total of 103 patients (60 percent) reported that they never injected drugs. The main routes of administration were smoking (124 patients, or 71 percent), injection (19 patients, or 11 percent), and intranasal use (12 patients, or 7 percent). For 58 subjects (33 percent), the current detoxification was the first inpatient treatment for substance abuse. Among the other patients, the number of previous admissions for substance abuse treatment, including detoxification, ranged from one to eight.

A total of 159 patients (91 percent) were voluntarily in treatment. For the patient cohort the mean±SD length of current stay in the detoxification unit was 19.8±18.9 days.

Statistical analyses

First, the number of predictor variables was reduced by testing significant differences in scores between the positive and negative outcome groups—those who were transferred to further treatment and those who were not. To avoid multiple t tests, two-group analysis of variance with univariate F tests was employed to identify differences on numeric variables between the two groups. Chi square tests (Pearson) were used to identify differences on nominal variables. All scales of the ASI, CMRS, SCL-90, and UCL, as well as age and days in the detoxification unit, were dependent variables in the analysis of variance; outcome group (positive and negative outcome) was the factor.

The variables that were found to be significantly different between the two groups were entered as predictor variables in a logistic regression with the group as the dependent variable. A stepwise logistic regression analysis was employed to determine the variables predicting transfer from the detoxification unit to further treatment. The probability level for stepwise entry and removal was set at .05.

Results

The positive outcome group consisted of 81 subjects (46 percent), and the negative outcome group consisted of 94 subjects (54 percent). The two groups did not differ in gender or ethnic background or in whether they lived alone. Negative outcome was more common among subjects for whom heroin was the primary drug of abuse than among subjects who reported other drugs as primary (χ2= 10.94, df=1, p=.001).

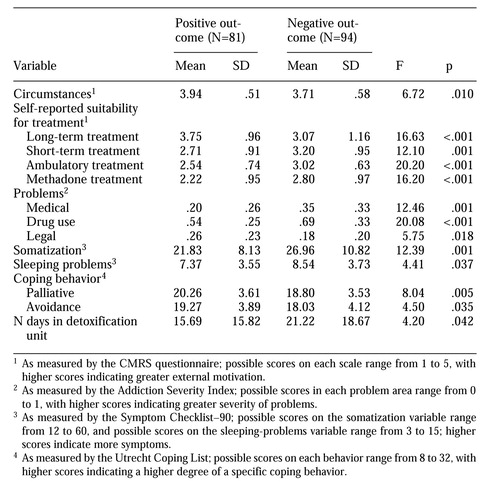

Table 1 presents the variables shown by the univariate F tests to indicate significant differences between the positive and negative outcome groups. For all other variables, no significant between-group differences (p<.05) were found.

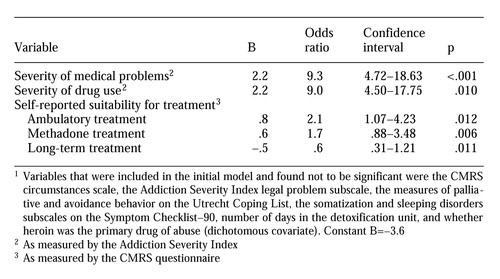

Outcome was used as a dichotomous dependent variable in the logistic regression model. The results of the logistic regression analysis, including the regression coefficient, odds ratio, and significance level, are summarized in Table 2. Based on the model, significant variables predicting outcome of detoxification were severity of medical problems, severity of drug use problems, and self-reported suitability for ambulatory treatment, methadone treatment, and long-term treatment. The overall regression equation was able to classify 73.7 percent of the patients correctly. In addition, the "pseudo proportion of variance," or R2 logit, of outcome explained by the five variables listed in Table 2 was .25. The R2 logit is represented by the equation [-2 logLnull-(-2logLmodel)]/-2logLnull and is similar to the R2 value in linear regression analysis (18).

The results of the logistic regression indicated that patients who had a negative detoxification outcome were more likely to have more severe medical problems and drug use problems, to perceive that they were more suitable candidates for ambulatory treatment and methadone treatment than for long-term treatment after detoxification, and to perceive that they were less suitable for long-term treatment after detoxification.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, treatment in a detoxification unit was successful for approximately half of the 175 subjects. This success rate corresponds with those in other studies addressing outcomes in inpatient substance abuse treatment settings (1,2). However, this rate is rather low compared with that in a recent outcome study of patients in an ambulatory detoxification program (9).

In the study reported here, the most important predictive factors for treatment outcome were severity of medical problems and severity of drug use. High scores on these dimensions were associated with an increased likelihood of negative outcome. One explanation may be that patients with more severe substance use problems experience increased withdrawal symptoms during detoxification, both physically and psychologically. If this is the case, to obtain higher retention rates, detoxification programs should focus more attention on withdrawal symptoms. For example, the effectiveness of combined clonidine and naltrexone treatment (19) to shorten the duration of detoxification and reduce the severity of the withdrawal syndrome should be further examined. In general, the finding of the importance of medical problems as a predictor of detoxification outcome should be confirmed by experimental studies.

Severe substance abuse problems before admission may result not only in withdrawal symptoms but in higher levels of craving during detoxification. Craving may in turn be related to negative outcome (20). Detoxification outcome studies that include more direct measures of craving and withdrawal symptoms are needed.

Some significant differences between the positive and negative outcome groups in the bivariate analysis did not meet inclusion criteria for the logistic regression model. These variables, such as somatization and sleeping problems (rated on the SCL-90), circumstances (rated on the CMRS), and legal problems (rated on the ASI), are likely to be highly intercorrelated with medical problems, drug use problems, or treatment suitability as measured by the CMRS scales. For example, persons with medical problems are also likely to have somatization and sleeping disorders, whereas patients with severe drug use problems may experience greater external pressure to enter treatment.

Although motivational factors have been suggested as a potentially strong predictor of retention in drug treatment in general (17,21), these findings could not be confirmed in our study. Only the variables of self-reported suitability for methadone, ambulatory, and long-term treatment were significant predictors of detoxification success. This finding suggests that self-reported suitability is a better predictor of the outcome of inpatient detoxification than internal motivation, readiness for treatment, and external circumstances.

An alternative explanation is that because most patients entered the detoxification unit voluntarily, overall CMRS scores were high, which thereby limited their role as a predictor. Although it may be questioned whether CMRS measures of motivational factors and voluntary treatment status are indexes of the same concept, it is likely that voluntary admission represents more than motivation for treatment. For example, voluntary patients may admit themselves to obtain temporary housing and decent meals.

It is interesting to compare the findings of this outcome study with outcome studies in other substance abuse treatment services. A main difference is that in this study demographic and social background variables, which are believed to be important predictors of substance abuse treatment success, were found to be poor predictors of inpatient detoxification outcome. Factors such as ethnic background, gender, age, and living situation were not correlated with detoxification outcome. Our sample may have been more homogeneous in social background than samples in other studies, which report more heterogeneity in ethnicity (9) and living situation.

In addition, the relatively long mean duration of detoxification in this study may indicate that predictors other than those measured in programs with shorter detoxification regimens, such as most U.S. programs, would be more appropriate. However, the number of days in the detoxification unit was not a significant predictor of treatment outcome in this study. Although univariate F tests showed that persons with a positive outcome spent a shorter time in the unit than those with a negative outcome, the difference was not found in the multivariate analysis.

Presumably, treatment duration is intercorrelated with the severity of drug and medical problems. Another difference between the program in this study and most U.S. drug treatment programs is that the therapeutic program was the same in this study for patients with different drugs of abuse except that opiate-dependent patients were put on methadone reduction regimens. Although univariate analysis revealed a smaller proportion in the positive-outcome group among whom heroin was the primary drug of abuse than in the negative-outcome group, the major drug of abuse was not a predictor of outcome.

In the past decade, much attention has been focused on co-occurring mental disorders among substance abuse patients. The results of this study indicate that the presence of psychopathological symptoms was not a predictor of outcome in the detoxification phase of drug abuse treatment. None of the psychopathology indicators—the ASI psychiatry subscale and the SCL-90 scales—were significant predictors in the regression analysis. It must be noted that the SCL-90 was administered before detoxification, and the scores may reflect drug-induced symptoms rather than psychopathology (22). In addition, none of the personal coping styles, as measured by the UCL, predicted detoxification outcome. This finding is in contrast with the finding that coping styles are related to outcome of substance abuse programs (8).

Prospective outcome studies in inpatient detoxification clinics are rather scarce. Because high rates of negative outcomes in this initial stage of substance abuse treatment greatly reduce the number of persons who might benefit from further treatment, more attention must be focused on completion of successful detoxification. This study indicates that predictors of positive detoxification outcome are different from predictors of positive outcome of other substance abuse treatment programs, such as rehabilitation. Adequate assessment of patients' medical condition and drug abuse severity may help clinicians recognize these problems and may allow them to develop strategies to better address them.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Chris van der Meer, M.D., Him Vishnudatt, B.A., and Judith Haffmans, Ph.D., for helpful comments. The study was financially supported by the substance abuse treatment department of Parnassia Psycho-Medical Centre in the Hague.

The authors are affiliated with the addiction department of Parnassia Research Centre, P.O. Box 53002, 2505 AA, the Hague, the Netherlands (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Variables found by univariate analysis to indicate significant differences between patients who successfully completed detoxification and those who did not

|

Table 2. Variables found in a multiple logistic regression to predict outcome of detoxification among 175 patients1

1. McCusker J, Bigelow C, Luippold R, et al: Outcomes of a 21-day drug detoxification program: retention, transfer to further treatment, and HIV risk reduction. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 21:1-16, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Stark MJ: Dropping out of substance abuse treatment: a clinically oriented review. Clinical Psychology Review 12:93-116, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Baekland F, Lundwall L: Dropping out of treatment: a critical review. Psychological Bulletin 82:738-783, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. De Leon G, Melnick G, Kressel D: Motivation and readiness for therapeutic community treatment among cocaine and other drug abusers. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 23:169-190, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, et al: Predicting response to alcohol and drug abuse treatment: role of psychiatric severity. Archives of General Psychiatry 40:620-625, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Hendriks VM: Addiction and Psychopathology: A Multidimensional Approach to Clinical Practice. Doctoral dissertation. Rotterdam, Erasmus University, medical faculty, department of addiction research, 1990Google Scholar

7. Gossop M, Green L, Phillips G, et al: Factors predicting outcome among opiate addicts after treatment. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 29:209-216, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Myers MG, Brown SA, Mott MA: Coping as a predictor of adolescent substance abuse treatment outcome. Journal of Substance Abuse 5:15-29, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Wiseman EJ, Henderson KL, Briggs MJ: Outcomes of patients in a VA ambulatory detoxification program. Psychiatric Services 48:200-203, 1997Link, Google Scholar

10. McLellan AT, Luborski L, Woody GE, et al: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26-33, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Hendriks VM, Kaplan CD, Van Limbeek J, et al: The Addiction Severity Index: reliability and validity in a Dutch addict population. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 6:133-141, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Derogatis LR: The Symptom Checklist-90—R: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual, 3rd ed. Minneapolis, National Computer Systems, 1994Google Scholar

13. Arrindell WA, Ettema H: Dimensionele structuur, betrouwbaarheid en validiteit van de Nederlandse bewerking van de Symptom Checklist-SCL90 [Dimensional structure, reliability, and validity of the Dutch Symptom Checklist-SCL90]. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor de Psychologie 36:77-108, 1981Google Scholar

14. Oldehinkel AJ, Koeter MW, Ormel J, et al: Omgaan met problematische situaties: de relatie tussen algemeen en situatiespecifiek "coping"-gedrag [Coping with difficult situations: the relation between general and situation-specific coping behavior]. Gedrag & Gezondheid 20:236-244, 1992Google Scholar

15. Westbrook MT: A classification of coping behavior based on multidimensional scaling of similarity ratings. Journal of Clinical Psychology 35:407-410, 1979Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Schreurs PJG, van de Willige G, Brosschot JF, et al: De Utrechtse Coping Lijst: UCL [The Utrecht Coping List]. Lisse, the Netherlands, Swets en Zeitlinger, 1993Google Scholar

17. De Leon G, Melnick G, Kressel D, et al: Circumstances, motivation, readiness, and suitability (the CMRS scales): predicting retention in therapeutic community treatment. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 20:495-515, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, et al: Multivariate Data Analysis, 4th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice Hall, 1995Google Scholar

19. O'Connor PG, Waugh ME, Carroll KM, et al: Primary care-based ambulatory opioid detoxification: the results of a clinical trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine 10:255-260, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Islam R: Relapse following withdrawal of drug addiction. British Journal of Psychiatry 163:699, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Ryan RM, Plant RW, O'Malley S: Initial motivations for alcohol treatment: relations with patient characteristics, treatment involvement, and dropout. Addictive Behaviors 20:279-297, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Franken IHA, Hendriks VM: Comorbidity of mental disorders with substance misuse. British Journal of Psychiatry 171:484, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar