The Educational Needs of Families of Mentally Ill Adults: The South Carolina Experience

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Family members of patients at South Carolina State Hospital in Columbia were surveyed to learn their needs for education, skill building, and support. METHODS: A random sample of 80 families participated in a telephone survey in 1995 to obtain information for development of a family program. Families were asked about their information and support needs in 13 areas, their preferences about the location and scheduling of family services, and barriers that might prevent them from participating. RESULTS: Respondents identified needs in several areas. The most frequent need, identified by more than 75 percent of families, was for advocacy in communicating with professionals and others. Twenty-nine percent of respondents reported that more contact with the social worker or physician would help improve their relationship with their ill relative. Families expressed the most interest in individualized sessions of family services (66 percent). Thirty-five percent of families were interested in informal support groups, such as the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, and 29 percent in formal support groups, such as those developed by mental health professionals. No special preference was noted when families were asked about site of educational and support services—at the hospital (48 percent), in the community (46 percent), or at home (48 percent). Transportation and distance were the chief barriers cited by family members (68 percent) to participating in family services. CONCLUSIONS: Results indicated that mental health professionals should continue efforts to engage families in a partnership for the benefit of the patient and the family and to help contain service costs.

The National Institute of Mental Health initiated community support programs in 1978 to address the comprehensive needs of persons with a chronic mental illness. The focus has been on needs assessment, crisis stabilization, psychosocial rehabilitation, and case management (1). One of the important functions of case managers is to coordinate and provide follow-up during transitions from hospital to community settings. This assistance prolongs community tenure.

Families frequently fill in the gaps in service delivery as "de facto case managers" (2), providing services that would otherwise substantially increase the cost of care for an individual. Unknowingly, they function as case managers more often than do mental health professionals (3). Studies have shown a positive relationship between family support and medication compliance, reduced number of readmissions to the hospital, and increased community tenure (4,5,6). To reduce family stressors and to reinforce the vital role the family plays in rehabilitation, families require support and education. Engaging families in the treatment process can significantly improve outcomes (7). The process of engaging family members or significant others requires considerable professional skill and wisdom by case managers.

Mental health professionals do not generally involve families of adults with mental illness in treatment (8,9,10). Although families have experiential knowledge of their loved one's disorder, professionals give them little factual information about the disorder (11,12). Information provided by professionals is often inadequate and vague (13) and not sufficient for family members to help their ill relative (14).

Research has provided a wealth of information about the needs of families caring for a relative with a serious mental illness. Biegel and his colleagues (14) compared data from two studies, one conducted in 1983 and one in 1991, of similar groups of families. The 1991 study found that mental health professionals did not actively involve family caregivers in the treatment of their ill relative and that the caregivers received little assistance from professionals in taking care of themselves or the rest of their family. Caregivers in the study reported that they wanted more extensive involvement with mental health professionals; of 13 educational and support services listed, they ranked "more communications with mental health professionals" as their greatest need (14).

Despite the documentation of needs, efforts by policy makers and mental health professionals to provide supportive services to family caregivers have been limited and infrequent (15). Mental health professionals are directed to focus their efforts on billable services. Services to the consumer are directly billable, but services to family members to help them adapt and cope may not be billable (16). Other obstacles for case managers are their large caseloads, which leave them little time to work with families, as well as the crisis orientation of much case management and clients' right to confidentiality (14). Awareness of the role families play in the treatment of the consumer is growing. Mental health professionals need to communicate with families to acquire information important for effective treatment (17).

This paper reports results of a survey of families of patients at South Carolina State Hospital in Columbia conducted to determine family members' needs for education, support, and skill building. The hospital is a public, centralized facility serving the psychiatric needs of adults and geriatric patients in long-term care. The aim of the survey was to determine educational, support, and skill-building needs of families who had a loved one in the hospital. Because the hospital is a long-term-care facility, it was unclear whether family members' needs for education, support, and skill building would be different from those of families whose ill relative was experiencing an acute onset.

The survey also attempted to understand family members' relationship with the patient and how the illness had affected the family. In addition, the survey asked families for their preferences about the site and schedule of delivery of family services.

Methods

The study, which was conducted in 1995, used a random sample of patients (20 percent) from each ward of the hospital—single-gender wards, open and closed wards, geriatric wards, and behavioral management units. Thus all patient subpopulations were represented in the study. A patient was excluded and another patient substituted if the patient did not have a family contact, the family did not have a telephone, or the interviewer could not contact the family. This process was continued until a sample of 80 patients with family contacts was reached.

Between October and December 1995, two trained staff members conducted a telephone survey with family members of the 80 patients. In each case, the interviewer ascertained that the person interviewed was considered the patient's primary caregiver. For purposes of this study, the primary caregiver was the family member who provided emotional and monetary support. In many cases families remain close to their ill relative but are unable to live on a day-to-day basis with the patient. In South Carolina patients who reside in the hospital receive between $45 and $60 a month for personal items such as toiletries and clothing, as well as snacks, cigarettes, and leisure activities. Most patients receive supplemental support from their families regardless of how long they have been in the hospital. This continued support of the patient was the criterion used to identify the primary caregiver.

The 52-item survey sought information about the patient and the family caregiver. Demographic data were obtained as well as information on the length of the current hospitalization and the effect the illness had on the family's lifestyle. Number of visits to the patient was used as an indicator of the family's involvement with the patient. Staff reviewed visitation records to confirm the number of reported visits.

Two survey questions were open ended. One asked what professionals could do to improve the family's relationship with the patient, and the second asked what in general could be done to improve the family's relationship with the patient. Questions were asked about the family's support network to learn whether family members had participated in groups specifically designed to address mental illness. Thirteen items asked about family members' needs for education, skill building, and support. Other questions asked about service preferences (location, site, and time of day). Respondents identified barriers to their participation in a proposed family service program.

Results

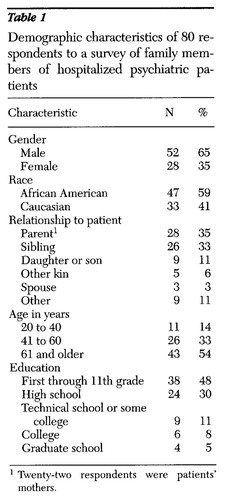

A total of 80 respondents, who were identified as patients' primary caregivers, completed the survey. According to the family profile developed from the survey data, primary caregivers were mostly parents or siblings. As Table 1 shows, 35 percent were parents, and 33 percent were siblings. Generally, the primary caregiver was 61 years old or older (54 percent). Educational levels, as shown in Table 1, were low; 48 percent of the respondents had not completed high school.

Fifty-two of the patients (65 percent) were men. Forty-seven patients (59 percent) were African American. The mean age of the patients was 53.4 years, with a range of 28 to 89 years. A majority of the patients had more than five admissions (45 patients, or 55 percent), and most had been mentally ill for more than ten years (57 patients, or 71 percent). For 61 patients (76 percent), the length of the current hospitalization was more than one year.

Fifty-four respondents (68 percent) reported that the patient's illness had a negative effect on the respondent's lifestyle; only one individual reported that the illness had made the family closer. Respondents generally reported they knew whom to call for support (61 respondents, or 76 percent), identifying family and friends as those who offered support. However, involvement in support groups was rare; 73 (91 percent) reported they had never attended a support group.

Forty-four survey respondents (55 percent) reported that they visited their hospitalized ill relative three times or more a year. A review of visitation records showed that 28 families (35 percent) visited the hospital two or three times a year, 14 families (18 percent) made one visit a year, and 22 families (28 percent) did not visit.

Seventy respondents (88 percent) reported that they did not want their relative to live with them after discharge. The interviewer briefly described a family education and support program that the hospital was developing and asked respondents to identify possible barriers to their participation. Transportation and distance were the chief barriers cited (54 respondents, or 68 percent), followed by caregiving responsibilities and age (47 respondents, or 59 percent) and work schedules (38 respondents, or 48 percent). Fifty-one respondents (64 percent) said they would be willing to call in advance to schedule an appointment for family services, and 38 (48 percent) said they would participate in family services if transportation was provided.

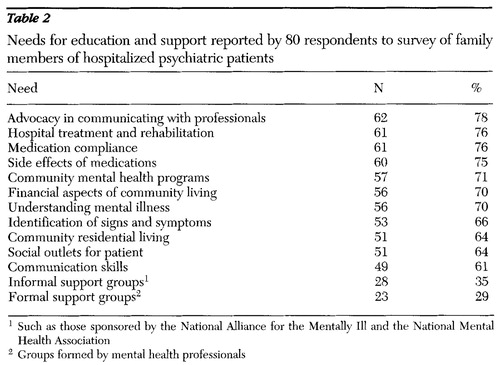

Table 2 presents responses to questions about families' educational and support needs. The greatest need, identified by 78 percent of respondents, was for advocacy, which was explained to family members during the survey interview as acting or speaking on their behalf to professionals about their ill relative. Education about hospital treatment and rehabilitation and about medication compliance issues were areas of second greatest need (76 percent each), followed by the need for education about side effects of medications (75 percent).

Many respondents (71 percent) wanted education about community mental health programs and financial aspects of living in the community (70 percent). Other educational needs were identification of signs and symptoms of illness (66 percent), community residential living (66 percent), social outlets for the patient (64 percent), and communication skills for the family (61 percent).

Only 35 percent of respondents reported being interested in participating in an informal self-help group such as those sponsored by the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill and the National Mental Health Association, and only 29 percent were interested in participating in formal support groups facilitated by professionals.

Families were asked to report their preferences for service location—at the hospital, in the community, or in the home—and the day and time of day. Responses were about equally divided among the three locations: 39 respondents (48 percent) preferred the hospital, 37 respondents (46 percent) the community, and 39 (48 percent) at home. (Respondents could choose more than one location.) Generally, families preferred Wednesday and Saturday for participating in family services, and ruled out Friday and Sunday. Those who preferred receiving family services at the hospital also preferred Wednesdays and Saturdays, and those who chose the community preferred Monday and Wednesday. The preferred time of day was 3 to 5 p.m.

An open-ended question asked what professionals could do to improve the family member's relationship with their ill relative. Most respondents answered in one of two ways. Twenty-eight (35 percent) reported desiring more contact with the social worker or physician. Forty-one respondents (51 percent) did not think anything else could be done. When asked what in general could be done to improve the family member's relationship with the ill relative, 58 respondents (73 percent) responded that nothing else could be done.

Discussion

A survey was undertaken to understand patients' families and identify their needs for psychoeducation and support. It was not surprising that families identified a strong need for advocacy in communicating with mental health professionals and a relatively weak need for support groups. In South Carolina support groups for families of people with mental illness report poor or inconsistent attendance. The cultural norm is not to "air out dirty linen" in front of others. In addition, most families report that when they ask mental health professionals about their relative's treatment, they either get no response at all or are not included in the treatment. Mental health professionals often discount family members' positive contributions to the treatment process. Families' needs for help in coping with and adapting to their relatives' mental illness are not considered. They often report a sense of powerless in the face of the authority of professionals.

Wasow (18) describes experiences that are very similar to those of many families of patients at South Carolina State Hospital. Distance, transportation, age, and other family caregiving responsibilities preclude families' involvement in the day-to-day life of the patient. Most family members have a high school education or less, and most do not have the resources to stay active in their adult relative's life, particularly when they are miles away.

Families have an experiential base of knowledge of their loved one's illness, but they often have little information about the illness. Program developers should be aware that even though some patients have been ill for a long time, their families may still need the same basic psychoeducation and services as families whose relative has only recently become ill (19,20).

To offer psychoeducation or education classes to families can be threatening. Many people may not know what "psychoeducation" means. Some family members thought that it was an education class to get a general equivalency diploma (GED). Going to class implies needing skills such as reading out loud. Educational materials and hand-outs may not be written at a level that participants can easily understand and may be full of professional jargon. For family members with less than a high school education, difficulty comprehending the materials can be a deterrent to participation.

In addition, the lives of many families have so often been disrupted by the patient's illness that they are continually trying to get back into a normal routine. They may regard participation in a class as a continued disruption.

The literature provides evidence that support groups are beneficial to families. However, to some families, attending a support group may seem like "telling your business in the street." In this survey only 35 percent of the respondents expressed interest in an informal support group, and even fewer, 29 percent, were interested in a formal support group. One study reported that families of lower socioeconomic status do not participate in support groups (14).

In terms of educational and support needs, the families in our survey expressed the most interest in individualized sessions (66 percent). Once a mental health professional develops rapport and a relationship with family members, the family may eventually be willing to participate in a support group. In any type of program, sensitivity to cultural issues is important. Fifty-nine percent of the families in our survey were African American.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight three major areas for continued attention: the process by which mental health professionals engage family members, the delivery of educational services to caregivers, and the resources and skill of the person providing educational information to families, as well as his or her knowledge of the mental health system.

More needs to be done to strengthen the relationship between family caregivers and mental health professionals. Research consistently confirms that educating and supporting caregivers is positively associated with prolonged community tenure and reduced recidivism rates. Mental health professionals, who often cite statutes about patients' confidentiality as the reason for not involving families in treatment, must find alternative solutions so that they can educate family members (21,22). They need to collaborate with family members using a competency-based approach that is built on families' strengths and is based on the belief that the family is doing the best it can. Families want more communication with mental health professionals and should be involved in treatment.

The delivery of educational services should occur in a setting that is nonthreatening to families. An assessment of family members' knowledge of their relative's illness allows for individualized teaching based on their self-reported knowledge of different subject areas. Families should also be asked how they learn best, with written materials, videos, or didactic discussions. Services should be available on evenings or weekends. Collaboration between the educational program and local support groups, such as the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, will help meet families' needs for emotional support and allow them to get to know families with similar problems. Because research has indicated that families of lower socioeconomic status do not participate in support groups, mental health professionals must find alternative methods to ensure that families receive needed services (23).

The family resource program at the South Carolina Department of Mental Health was developed using the theoretical concepts described in this paper. Professionals in the program are competent in delivering culturally sensitive services, they understand how the mental health system works, and they have clinical skills to engage families. Services are provided on an outreach basis, in collaboration with the local chapter of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marie Huff, M.S.W, and Terri Morgan, M.A., for their help with this project.

When this work was done, Ms. Gasque-Carter was a program coordinator in the family resource program of the transition services department at South Carolina State Hospital, and Ms. Curlee was director of the department. Currently, Ms. Gasque-Carter is a program consultant for the office of continuity of care in the South Carolina Department of Mental Health, and Ms. Curlee is a program coordinator in that office. Send correspondence to Ms. Gasque-Carter at 7901 Farrow Road, Administration Building, Columbia, South Carolina 29203 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of 80 respondents to a survey of family members of hospitalized psychiatric patients

1 Twenty-two respondents were patients' mothers.

|

Table 2. Needs for education and support reported by 80 respondents to survey of family members of hospitalized psychiatric patients

1 Such as those sponsored by the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill and the National Mental Health Association

2 Groups formed by mental health professionals

1. Moran AE, Freedman RI, Sharfstein SS: The journey of Sylvia Frumkin: a case study for policy makers. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 35:887-893, 1984Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Solomon P: Moving from psychoeducation to family education for families of adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 47:1364-1370. 1996Link, Google Scholar

3. Intagliata J, Willer B, Egri G: Role of the family in case management of the mentally ill. Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:699-708, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hogarty GE, Anderson CM, Reiss DJ, et al: Family psychoeducation, social skills training, and maintenance chemotherapy in the aftercare treatment of schizophrenia: I. one-year effects of a controlled study on relapse and expressed emotion. Archives of General Psychiatry 43:633-642, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Falloon IRH, Boyd JL, McGill CW, et al: Family management in the prevention of exacerbation of schizophrenia: a controlled study. New England Journal of Medicine 306:1437-1440, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Dixon LB, Lehman AF: Family interventions for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:631-643, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kanter J: Engaging significant others: the Tom Sawyer approach to case management. Psychiatric Services 47:799-801, 1996Link, Google Scholar

8. Bernheim KF, Switalski T: Mental health staff and patient's relatives: how they view each other. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:63-68, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Biegel DE, Yamatani T: Self-Help Groups for Families of the Mentally Ill: Research Perspectives in Family Involvement in the Treatment of Schizophrenia. Edited by Goldstein MZ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1986Google Scholar

10. Hatfield AB, Firestein R, Johnson DM: Meeting the needs of families of the psychiatrically disabled. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 6:27-40, 1982Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Spaniol L, Jung H, Zipple A, et al: Families as a resource in the rehabilitation of the severely psychiatrically disabled, in Families of the Mentally Ill: Coping and Adaptation. Edited by Hatfield A, Lefley HP. New York, Guilford, 1987Google Scholar

12. Holden D, Lewine RRJ: How families evaluate mental health professionals, resources, and effects of illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 8:626-633, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Pfeiffer E, Mostek M: Services for families of people with mental illness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:262-264, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Biegel DF, Song L, Milligan SE: A comparative analysis of family caregivers' relationships with mental health professionals. Psychiatric Services 46:477-482, 1995Link, Google Scholar

15. Benson PR: Deinstitutionalization and family caretaking of the seriously mentally ill: the policy context. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 17:119-138, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Wright ER: The impact of organizational factors on mental health professionals' involvement with families. Psychiatric Services 48:921-927, 1997Link, Google Scholar

17. Hansom JG: Families' perceptions of psychiatric hospitalization of relatives with a severe mental illness. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 22:531-541, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Wasow M: A missing group in family research: parents not in contact with their mentally ill children. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:720-721, 1994Google Scholar

19. Ascher-Svanum H, Lafuze JE, Barrickman PJ, et al: Educational needs of families of mentally ill adults. Psychiatric Services 48:1072-1074, 1997Link, Google Scholar

20. Bernheim KF, Switalski T: Mental health staff and patient's relatives: how they view each other. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:63-68, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

21. McPeak WR: Family intervention models and chronic illness: new implications from family systems theory. Community Alternatives: International Journal of Family Care 1:53-63, 1989Google Scholar

22. Petrila JP, Sadoff RL: Confidentiality and the family as caregiver. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:136-139, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

23. Finley LY: The cultural context: families coping with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 21:230-239, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar