The Use of Physical Restraints in Polish Psychiatric Hospitals in 1989 and 1996

Abstract

The use of physical restraints in 11 locked psychiatric wards in Warsaw, Poland, was examined in 1989 and 1996 to determine whether the implementation of the Mental Health Act in 1995 and other political transformations changed this psychiatric practice. All episodes of restraint were documented during a one-month period in both years. Significantly more episodes of restraint occurred in 1996, but the average duration of each episode decreased, the number of episodes per patient fell, and the proportion of episodes due to patient aggression increased. Findings indicate that use of restraint was less arbitrary in 1996, which is likely attributable to the replacement of local institutional rules by national regulations controlling the use of restraint in psychiatric practice.

Psychiatry has always used coercive tactics to control patients' aggressive behavior and will probably continue to do so. The practice of restraining patients occurs all over the world, independently of the political system. For many years in Poland, no laws governed this practice.

In January 1995, a few years after the change in the political system from totalitarian to democratic, the Mental Health Act was passed. The act, which acknowledged the human rights of psychiatric patients, addressed the prevention of psychiatric disorders and established rules for psychiatric service organizations. It also included rules about the use of coercion or compulsion.

In accordance with the act, compulsion can be used in certain situations: when a patient engages in aggression involving a direct danger to either health or life, endangers public safety, or engages in violent destruction or damage to objects. For patients admitted to a hospital against their will, compulsion can also be used in carrying out the therapeutic actions necessary to address the factors that led to hospital admission or to prevent patients from leaving the hospital. These indications vary from the those described in the American Psychiatric Association's task force report on seclusion and restraint (1). The difference is that in Poland restraints are not used as contingencies in the therapy of dangerous behaviors or to decrease stimulation of patients.

This study addressed the question of how the use of restraints changed in Poland during the period of important political transformation between 1989 and 1996. The study examined the frequency of use of restraints, the duration of episodes of use, and the reasons for use.

Methods

The study was conducted in 11 locked wards of state district psychiatric hospitals. Seven wards were in two large psychiatric hospitals, and four were run by a scientific institute. One of the latter was a psychiatric ward in a general hospital. The wards were studied twice, in 1989 and in 1996, after the implementation of the Mental Health Act in 1995. The size of the wards ranged from 13 to 71 patients. The average age of patients was 43 years. All were Caucasian.

In 1989 and 1996 a one-month period of observation was implemented on the wards during which every episode of restraint was documented. The term "restraint" refers to traditional four-point leather restraint, a camisole, or restraining sheets.

Previous studies used several methods to measure rates of restraint (2). The study reported here measured the rate in two ways: as the number of episodes of restraint per patient (the number of episodes divided by the total number of patients) and as the proportion of patients restrained.

Each restraint episode during the month of observation was described with the help of a special chart devised by the authors. The data were organized according to the categories suggested by Soloff (3). The chart elicits information about the restrained patient, the circumstances surrounding the episode of restraint, and the causes of the episode.

Kellam's Information Form (4) was used to determine the global pathology level on each ward, including the frequency of bizarre and aggressive behaviors. Other information obtained about each ward related to the equipment, the therapeutic program, and the rules governing the ward.

Data obtained in 1989 and in 1996 were compared to look for significant differences; associations between variables were determined using Pearson's correlation coefficient.

Results

In the time between the two research periods, the wards did not change fundamentally. In 1989 and 1996 the staff-patient ratios and diagnostic rates were similar. Patients' demographic characteristics and measures of chronicity of illness were also similar, as was ward overload, or the ratio of needed beds to actual beds. The global pathology level in each ward, as measured by Kellam's Information Form, also remained unchanged.

In 1989 a total of 452 patients were hospitalized on the 11 wards, 207 men and 245 women. In 1996 a total of 414 patients were hospitalized, 163 women and 251 men.

In 1989 a total of 98 patients were restrained. Fifty-three of them (54 percent) met ICD-9 criteria for endogenous psychoses, mainly schizophrenia. The next most common diagnosis was alcohol dependence, which was recorded for 23 (23 percent). In 1996 the total number of restrained patients was 65. Forty-eight of them (74 percent) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and eight (11 percent) had a diagnosis of alcohol dependence.

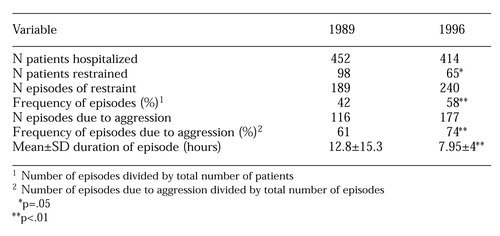

Table 1 shows the number of episodes per patient, the proportion of patients restrained, the percentage of episodes of restraint that were due to aggression, and the mean duration of the episodes. Significantly more episodes of restraint occurred in 1996 than in 1989; the number of episodes increased in each of the wards studied. However, the number of episodes per patient fell, as did the average duration of each episode. In addition the proportion of episodes that were due to patient aggression increased.

No associations were found between these measures and any demographic or diagnostic variable or any of the variables related to physical conditions on the ward. Although some studies have noted that rates of restraint differ between men and women, no differences were found in this study except a statistically insignificant tendency to restrain men for longer periods than women.

Wards with high global pathology levels as measured by the Kellam's index had higher rates on three measures—the frequency of restraint episodes, the percentage of patients restrained, and the percentage of episodes due to aggression. The Pearson's correlation coefficients were .66 (p=.05), .69 (p=.02), and .54 (p=.1), respectively.

The duration of restraint was correlated with the patient-staff ratio. On wards with more patients per staff member, episodes of restraint were longer (r=.7, p=.02).

Discussion and conclusions

Although episodes of restraint occurred more frequently in 1996 than in 1989, the proportion of patients who were restrained fell, patients were restrained for a shorter time, and restraint was used much more often to address aggressive behavior. Until the Mental Health Act was adopted in Poland in 1995, the use of compulsion in psychiatric practice was governed by local institutional rules. The finding of a greater proportion of episodes attributed to aggression in 1996 indicates that use of restraint has become much less arbitrary and that the practice is more controlled.

The study could not determine to what extent the effect was due to the Mental Health Act. The period covered by the research was a time of the major political and social change in Poland. The changes in social awareness and the democratization of life played an important role in the transformation of hospital practices; for example, many hospitals created the position of a patients' rights spokesperson.

The study proved that use of restraints could be considerably modified. We believe that continuous monitoring of the use of restraints and analysis of how procedures vary over time can help prevent abuse.

Acknowledgment

The research was funded by the Helsinki Human Rights Foundation.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the Medical University of Warsaw, Ul. Nowowiejska 27,00-665 Warsaw, Poland (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Use of physical restraint in 11 locked psychiatric wards in Poland before and after implementation of the Mental Health Act in 1995

1. The Psychiatric Uses of Seclusion and Restraint. Task Force Report 22. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1985Google Scholar

2. Fisher WA: Restraint and seclusion: a review of the literature. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1584-1591, 1994Link, Google Scholar

3. Soloff PH: Behavioral precipitants of restraint in the modern milieu. Comprehensive Psychiatry 19:179-184, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Kellam SG, Shmelzer, JL, Berman A: Variation in the atmosphere of psychiatric wards. Archives of General Psychiatry 14:561-570, 1966Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar