Mental Health Benefit Limits and Cost Sharing Under Managed Care: A National Survey of Employers

Abstract

Mental health services experts suggest that managed care diminishes the need for arbitrary benefit limits and consumer cost-sharing. Data from 577 health plans were used to test the hypotheses that health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and carve-out plans are less likely to use benefit limits or service exclusions, have more generous limits, and have lower cost-sharing requirements than non-HMOs and non-carve-out plans. The results show that HMOs were more likely to use service exclusions and did not make less use of benefit limits. Carve-outs were less likely to use some coverage exclusions. Comparisons of the stringency of limits and cost-sharing provisions did not show consistent differences.

Managed mental health care has been welcomed as a cost-containment strategy that applies professional judgment to obtain "more appropriate … matching of patients to treatment and … altering (of) inefficient treatment patterns" (1). It is said that by using professional judgment and sound care-management protocols, managed care plans diminish the need to contain costs through arbitrary benefit limits and high consumer cost-sharing requirements. Yet recent research indicates that health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and carve-outs are actually more likely to use some types of benefit limits (2,3).

This paper provides a detailed comparison of the use of benefit limits and cost-sharing specific to mental health care by health plans in a national survey of 577 employer-sponsored plans. We compared both the types of limits and cost-sharing provisions used and the stringency of these provisions. Comparisons across types of plans tested for differences between HMOs and non-HMOs and between carve-out and non-carve-out plans.

Methods

Data collection and respondents

We sought information on health benefits from 1,433 employers with active long-term-disability insurance policies with UNUM, a major disability insurance provider. Selection criteria included being a UNUM customer over the preceding three years and having at least 300 covered lives on the long-term-disability policy at some time during that three-year period.

Employers received a mailed questionnaire in the latter half of 1996 and were asked to send in summary plan descriptions or a detailed plan abstract form for each health plan offered to their employees. Data were obtained on 577 health plans offered by 250 employers. Although the overall response rate was low, it is comparable to rates in other mail surveys of employers. Moreover, complete data on all mental health benefit questions were obtained for every respondent and every health plan. No evidence of response bias was found. Detailed comparisons showed essentially no respondent-nonrespondent differences in descriptive characteristics, such as size of the employer's organization, industry, or region.

Respondent firms were located in the following geographic regions: 38.8 percent were in the East, 27.2 percent in the East Central region, 17.2 percent in the West Central region, and 16.8 percent in the West. A total of 27.7 percent were services firms, and 24.9 percent were manufacturing firms. Other types of firms accounted for 47.4 percent of respondents.

Among the 241 respondents who reported their total number of employees, the mean was 1,749. Applying this figure to all respondent firms implies that more than 437,000 employees were represented in the survey data. Respondent firms ranged in size from 21 to 27,519 employees; more than 95 percent reported having more than 200 employees.

Classification of health plans

Each plan was initially classified as an HMO or a non-HMO based on the language in its summary plan description or plan abstract. We reviewed plan information to verify that all HMOs included restrictions on the providers from whom treatment could be sought under "in-network" benefit provisions. HMOs with coinsurance for routine ambulatory care were reclassified as non-HMOs. Preferred provider organizations (PPOs) with small copayments rather than coinsurance for routine ambulatory care were reclassified as HMOs. Plans were coded as mental health carve-outs if their summary plan description identified a different organization as the contact for authorization, review, coordination, and administration of mental health benefits.

HMOs constituted 37.4 percent of plans; non-HMOs were split fairly evenly between standard fee-for-service plans (28.4 percent of the plans) and PPOs (34.1 percent). In all, 111 plans included a mental health carve-out. The proportion of plans with carve-outs was twice as high for both HMO and PPO plans (22.2 percent and 23.4 percent, respectively) as for fee-for-service plans (10.4 percent).

Data analysis

We used chi square and t tests to analyze differences in use of limits and cost-sharing between HMOs and non-HMOs and between carve-outs and non-carve-outs. We excluded from our analysis four of the 577 plans, including one HMO and three non-HMOs, that did not provide any mental health coverage.

Results

Mental health and substance abuse exclusions

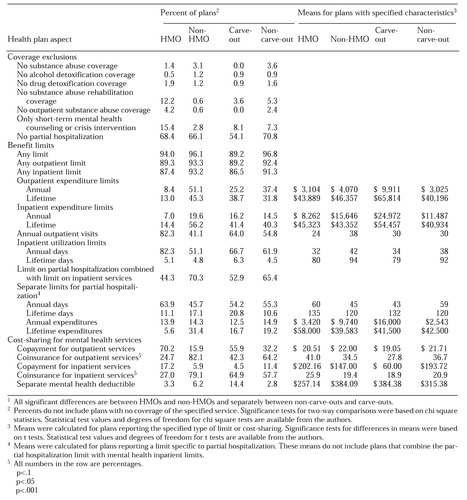

Table 1 shows the results of the comparison of HMOs and non-HMOs and the comparison of carve-outs and non-carve-outs. (Results of the comparison of PPOs and fee-for-service plans are available from the authors.) Carve-outs were significantly less likely to have an overall exclusion for substance abuse treatment. HMOs were significantly more likely to exclude coverage for substance abuse rehabilitation and to exclude coverage for outpatient substance abuse treatment. HMOs were more likely to limit mental health coverage to short-term treatment for acute episodes or crisis intervention. Carve-outs were less likely to exclude partial hospitalization services from coverage.

Mental health benefit limits

The overwhelming majority of plans included specific limitations. Carve-out plans were less likely to impose any specific limits, however, and HMOs were less likely to impose specific limits on inpatient services. (All data on HMOs' limits reported here are for in-network providers. See Sturm and McCulloch [4] for 1996 data on limits for carve-outs, including non-network providers.)

HMOs made less use of expenditure limits. Carve-out and non-carve-out plans looked alike in their use of expenditure limits, except that carve-outs were less likely to use annual dollar limits for outpatient services. In each plan category, less than 2 percent of plans had lifetime utilization limits. HMOs were more likely than non-HMOs to use annual visit and day limits, while the corresponding differential for carve-outs was significant only for visit limits.

HMOs had significantly more stringent levels of annual outpatient and inpatient utilization limits than non-HMOs. Analogous results for partial hospitalization were mixed. Both HMOs and carve-outs were significantly less likely to combine the partial hospitalization limit with their inpatient benefit limit, which suggests less stringent restrictions for these plans. Conversely, among plans with separate partial hospitalization limits, annual day limits were significantly higher for HMOs and significantly lower for carve-out plans. Annual dollar limits, however, were significantly higher for carve-out plans.

Cost-sharing provisions

HMOs were more likely to use copayments and less likely to use coinsurance than were other types of plans. Carve-out plans were more likely to use outpatient copayments and mental health deductibles and less likely to use outpatient coinsurance and inpatient copayments.

HMOs using coinsurance had significantly higher coinsurance rates than non-HMOs using coinsurance. Outpatient coinsurance and inpatient copayment levels were significantly lower in carve-out plans.

Discussion and conclusions

Although managed care is seen as reducing the need for benefit limits and consumer cost-sharing, this optimistic view is somewhat inconsistent with our results. Why do employers continue to offer plans with arbitrary limits and substantial consumer cost-sharing, rather than rationing services based on informed provider judgments?

One explanation is that employers and managed-care plans have been too single-minded in pursuing cost containment (5,6,7). A second explanation is that most carve-out contracts do not include substantial risk-sharing arrangements for the carve-out provider (8), so health plans or employers may be reluctant to dispense with benefit limits. A third possibility is that employers and health plans need more education about behavioral health care management before they appreciate the net advantages of eliminating arbitrary benefit limits. A fourth possibility is that the care management protocols and provider accountability mechanisms are not yet refined enough to completely replace limits.

Our data predated implementation of the 1996 Mental Health Parity Act, which proscribed unequal dollar benefit limits. However, we doubt that our conclusions would change with more recent data. Excluding results pertaining to dollar limits would not alter our overall conclusions. Moreover, our data show that dollar limits are less frequently applied in HMOs and, for outpatient services, in carve-out plans, so these plans will be less affected by the act. Recent anecdotal data suggest that dollar limits have mainly been replaced by utilization limits, rather than eliminated, in response to the act (9).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported under a contract with UNUM and by National Institute of Mental Health grant MH-43703 to the Center for Research on Services for Severe Mental Illness at Johns Hopkins University.

Dr. Salkever is professor of health economics and Ms. Shinogle is a doctoral candidate in the department of health policy and management at Johns Hopkins University, Hampton House, Room 429, 624 North Broadway, Baltimore, Maryland 21205 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Goldman is professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore.

|

Table 1. Mental health care coverage exclusions, benefit limits, and cost-sharing arrangements among 577 health plans grouped by whether or not the plan is a health maintenance organization (HMO) or a mental carve-out1

1. Frank RG, Koyanagi C, McGuire TJ: The politics and economics of mental health parity laws. Health Affairs 16(4):108-119, 1997Google Scholar

2. Buck JA, Umland B: Covering mental health and substance abuse services. Health Affairs 16(4):120-126, 1997Google Scholar

3. Jensen GA, Rost K, Burton RP, et al: Mental health insurance in the 1990s: are employers offering less to more? Health Affairs 17(3):201-208, 1998Google Scholar

4. Sturm R, McCulloch J: Mental health and substance abuse benefits in carve-out plans and the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996. Journal of Health Care Finance 24(3):82-92, 1998Google Scholar

5. Ford WE: Medical necessity: its impact on managed mental health care. Psychiatric Services 49:183-184, 1998Link, Google Scholar

6. Torrey EF: Is for-profit managed care an oxymoron? Psychiatric Services 49:415, 1998Google Scholar

7. Sharfstein SS: The high cost of spending less on care. Psychiatric Services 49:1523, 1998Link, Google Scholar

8. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Sturm R: Costs and use of mental health services before and after managed care. Health Affairs 17(2):40-52, 1998Google Scholar

9. Pear R: Insurance plans skirt requirement on mental health. New York Times, Dec 26, 1998, p A1Google Scholar