Clinical Characteristics and Service Use of Persons With Mental Illness Living in an Intermediate Care Facility

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study examined the characteristics of residents living in a 450-bed intermediate care facility for persons with severe mental illness in Illinois and sought to determine the factors predicting their utilization of mental health services. METHODS: Data on 100 randomly selected residents with a chart diagnosis of schizophrenia were collected using chart review and interviews. Data for 78 residents whose diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder was confirmed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV were included in the analyses. RESULTS: Fifty-three percent of the residents used facility-based specialty mental health services beyond medication management, such as group therapy or a day program. Persons with the least severe psychiatric illnesses and with higher levels of motivation for overall care used the most mental health services. Thirty-five percent of the residents had been discharged to an inpatient psychiatric unit during the previous year. Residents most likely to be discharged to those settings were young men with a history of homelessness who refused facility-based health services. CONCLUSIONS: Despite recent policy-driven efforts to improve care in this intermediate care facility for persons with mental illness, the facility continues to have problems addressing the mental health needs of the residents.

Over the past 40 years, efforts to deinstitutionalize patients in the public mental health system have led to a movement of persons with mental illness from state psychiatric hospitals to community-based services (1). Deinstitutionalization was designed partly to put an end to custodial care of persons with mental illness by creating community alternatives to state hospitals. This trend has led to lower state hospital censuses (2,3) and even to the elimination of state-operated hospitals in some states. However, nursing homes have become a significant residential alternative to state hospitals within the mental health service delivery system (4,5).

The institutional shift from state hospitals to nursing homes resulted in large part from two factors. First, the rush to deinstitutionalize state hospital patients occurred before the development of alternative residential opportunities (4,6,7). Second, Medicaid reimbursement strategies favored funding of nursing home placements rather than psychiatrically focused alternatives for persons with severe mental illness. The financial incentives for states and eligibility requirements channeled many persons with mental illness into nursing homes with few opportunities for psychiatric services and undermined the development of a full range of outpatient services and residential treatment programs (8,9).

Research on outcomes of nursing home care in the last two decades found high levels of medication use and low levels of psychosocial treatment, suggesting that nursing homes primarily served custodial care functions in the mental health care system (10,11,12,13,14). Further, research has documented instances in which persons with mental illness were inappropriately admitted to nursing homes on the pretext that they needed medical care (10). Another study found that many nursing home residents did not require physical health care but that few mental health service alternatives were available to them (15). Although little attention has been paid to nursing homes recently, the outcomes of past research documenting their poor effectiveness in meeting the mental health care needs of residents raise questions about the continued role of these facilities in the mental health services system.

Since this early body of research was done, nursing home reform associated with the Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA-87) has mandated changes in the care of persons with mental illness. The reform was primarily concerned with establishing the appropriateness of care for mentally ill patients in nursing homes and with the discharge of those who did not need nursing home care to alternative placements (13). The reform stimulated the development and expanded use of intermediate care facilities and of intermediate care facilities for the mentally ill, both of which served persons with severe mental illness without significant medical needs.

Intermediate care facilities were developed as rehabilitative institutions and were intended to provide lower levels of nursing care and medical supervision than skilled nursing homes. Thus intermediate care facilities could use fewer staff and staff with fewer educational credentials compared with nursing homes. These facilities became a desirable alternative placement for persons with mental illness because the facilities had to meet less stringent regulatory demands for medical need but were eligible for federal Medicaid reimbursement. Mentally ill persons qualify for mental health services under Medicaid in an intermediate care facility as long as fewer than 50 percent of all residents in the facility have a psychiatric diagnosis.

Few research studies have examined the mental health services received by residents living in intermediate care facilities. To plan for research on the outcomes of these services, the nature and needs of persons currently served by intermediate care facilities should be assessed. The study reported here explored the determinants of mental health service use in intermediate care facilities by examining the clinical characteristics of residents living in an intermediate care facility in Illinois, analyzing data on their receipt of mental health services, and identifying predictors of residents' use of mental health services and discharge to a psychiatric inpatient setting. Recent research suggests that schizophrenia is the most common psychiatric diagnosis among nursing home residents (16). Therefore, the study reported here examined mental health service utilization by nursing home residents with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Methods

Sample and procedure

The study was conducted in an intermediate care facility in a large city in Illinois between August 1996 and February 1997. The study setting had formerly been an intermediate care facility for the mentally ill and had been redesignated as an intermediate care facility six months before the study. The study setting did not differ in types and levels of staffing, health services provided, or residents' admitting diagnoses before and after its redesignation as an intermediate care facility.

The facility had 450 beds on six resident floors. One hundred residents with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were randomly selected from facility records and asked to participate in the study. Replacement sampling was used to obtain a final sample of 100. Residents who were unable to give informed consent were excluded from the study. A total of 109 residents who were eligible for the study were approached to participate before the final sample of 100 was obtained. Nine residents refused, for an overall response rate of 92 percent.

Informed consent was obtained from each resident who agreed to participate. Clinical assessments were completed by graduate students who were trained to use the assessment measures.

Data collection

Residents' charts were reviewed to obtain background information on their demographic characteristics, psychiatric and medical diagnoses, history and duration of outpatient and inpatient mental health service use, length of current facility admission, and family contact. Data were also collected on treatment variables, including use of psychotropic medication, whether they were restricted to the facility, whether they participated in activities such as social events and art classes provided in the facility, and use of mental health services provided at the facility, such as group, individual, and family therapy, workshops, and day treatment.

To assess the level of severity of residents' psychiatric illness, the Severity of Psychiatric Illness (SPI) measure (17,18) was used. The SPI is a case-mix measure that can be used retrospectively and prospectively. It allows for the assessment of clinical status on a set of 21 dimensions with demonstrated reliability and relationships to mental health service use and outcomes. Dimensions are categorized according to risk behaviors, such as suicide potential and danger to others; complications of mental illness, including substance abuse and impairment of self-care; and complications affecting treatment, such as patients' motivation and knowledge of illness. Information for completion of the SPI was obtained from charts, interviews with residents, and discussions with staff. An interrater reliability of .82 was achieved for this instrument in this study.

The Short-Form General Health Survey (SF-12), a reliable, valid, and widely used measure of health status (19), was used during structured interviews to obtain information on residents' health status. In addition, residents' charts were reviewed to obtain data on health status. The presence of chronic physical illnesses, such as diabetes, heart disease, or HIV, was recorded on the SPI as a medical complication to the mental illness.

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (20,21) was used to confirm psychiatric diagnoses. Interrater reliability of .92 for clinical diagnoses was obtained in this study.

A semistructured interview was used to address consumers' preferences in mental health services. This measure gathered information about residents' previous use of inpatient and outpatient mental health services, their perceptions about the positive and negative aspects of these services and about their current nursing home care, their satisfaction with current mental health services, and their goals and concerns for the future.

The Barthel Activities of Daily Living Index (22) was used to document residents' need for assistance. This scale covers ten self-care activities: bathing, dressing, grooming, toileting, transferring from bed to chair, mobility, walking up stairs, bowel and bladder continence, and feeding. Each chart was reviewed to assess the resident's level of physical independence using this measure. The Barthels Activities of Daily Living Index has demonstrated adequate levels of reliability and validity (23).

Results

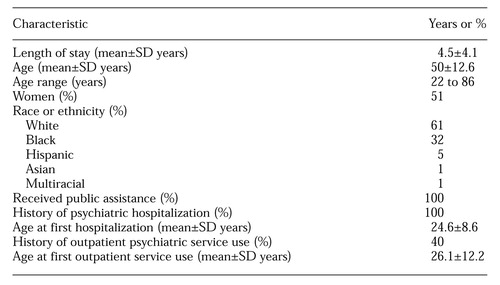

Table 1 presents background information for the study participants. Chart diagnoses were verified using the SCID. For most residents, information on the origin of the chart diagnosis was not available. Only 51 percent of the SCID diagnoses matched the chart diagnoses. Twenty-five residents had a chart diagnosis of schizophrenia, and 75 had a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder. The SCID identified a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder for 78 residents.

The SCID identified a variety of diagnoses for the remaining 22 residents, including depression for eight residents, bipolar disorder for four, anxiety disorders for two, psychotic disorder not otherwise specified for four, alcohol abuse in remission for two, drug-induced psychosis for one, and delusional disorder for one. Eighteen of the 22 residents with other psychiatric disorders, or 82 percent, had a chart diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder. There were no demographic differences between this subgroup and the entire sample.

Several important differences in clinical status were found between persons with a SCID diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and persons with other SCID diagnoses. The SPI was used to compare the clinical characteristics of the diagnostic groups. Analysis of variance revealed that residents with either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder had more severe psychiatric illness than residents with other psychiatric disorders (F=4.64, df=2,96, p<.02). Those with either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder had lower levels of community adjustment (F=6.28, df=2,96, p<.003), living skills (F=4.16, df=2,96, p<.02), and interpersonal skills (F=5.68, df=2,96, p<.005), compared with those with other psychiatric disorders.

In addition, 45 percent of all participants with a SCID diagnosis of either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder also had a history of substance abuse or dependence, compared with 27 percent of participants with other psychiatric disorders. Further, 19 percent of residents with either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder had a current substance use disorder, compared with none of the residents with other psychiatric disorders, a significant difference (χ2=4.98, df=1, p<.03).

These results suggest significant case-mix differences between residents with a SCID-confirmed diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and those with chart diagnoses of those disorders that were not confirmed by the SCID. To maintain the homogeneity of the sample, given differences in psychiatric illness and co-existing substance use, the analyses that follow were conducted with data on the 78 residents with SCID-confirmed diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Residents with either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were grouped together in the analyses because there were no statistically significant demographic differences between residents with the two diagnoses. In addition, treatment data suggest that these two diagnostic groups appear to be closely related (24,25,26), and service research studies usually combine these groups (27,28,29,30).

Utilization of mental health services

All 78 residents in the sample used medication management services provided by the facility. Forty-one residents, or 53 percent, used other facility-based mental health services. Thirty of those residents, or 73 percent, used one service, and 11 residents, or 17 percent, used two services. Specifically, two residents, or 3 percent, received individual psychotherapy, and 26 residents, or 33 percent, received group therapy. None of the residents received family therapy. Twenty-four residents, or 31 percent, were involved in psychosocial rehabilitation in either a workshop or a day program format. (Percentages do not total to 100 because residents could receive more than one type of service.)

All 78 residents were asked if they would like more contact with a mental health professional. Thirty-two percent were content with current levels of mental health services, 27 percent did not want increased contact with a mental health professional, 26 percent expressed a desire for increased contact, and 16 percent expressed an interest in lower levels of contact.

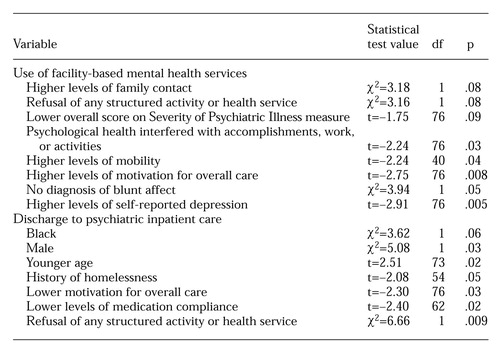

A series of univariate tests was done to identify variables that might be potential predictors of mental health service use. Results of univariate analyses are presented in Table 2.

The potential predictors of mental health service use that were identified in the univariate analyses (p<.05) were used in a logistic regression analysis. The results of the overall logistic regression analysis were significant (χ2=20.81, df=5, p<.001). The overall regression analysis accurately predicted whether a person used mental health services in 67 percent of cases. A higher level of motivation for overall care was the only variable that significantly predicted mental health service use (Wald statistic=4.15, df=1, p<.05).

Psychiatric inpatient utilization

Twenty-seven residents, or 35 percent, were discharged to an inpatient psychiatric unit within the previous year, and nine residents, or 33 percent, experienced multiple inpatient visits. There was no association between diagnosis and discharge to an inpatient psychiatric unit.

Potential predictors of discharge to a psychiatric inpatient unit that were identified in the univariate analyses (p<.05) were used in a logistic regression analysis (Table 2). The results of the overall logistic regression analysis were significant (χ2=24.04, df=7, p<.001), and whether a person was discharged to an inpatient unit was accurately predicted in 68 percent of cases. A history of homelessness was the only variable that significantly predicted use of inpatient services (Wald statistic=3.71, df=1, p<.05).

Discussion

Nursing home reform resulted in expanded use of intermediate care facilities for persons with mental illness. Data reported here suggest that these facilities continue to have problems addressing the mental health needs of residents with severe mental illness. Consistent with past research (10,11), the study findings suggest that the facility where the study was done functioned primarily as a provider of custodial care. Only about half of all residents used any specialty mental health services beyond medication management. One-third of the residents who did not refuse mental health services did not receive any services other than medication management. These findings suggest that the facility focused primarily on symptom management and made little attempt to habilitate or rehabilitate patients.

The results also show that residents with the most severe psychiatric illnesses used the fewest mental health services offered by the facility. However, the study could not discern whether mental health service use resulted in less severe symptoms or whether residents with less severe symptoms were more likely to use services. Future research should examine clinical outcomes over time.

About one-third of the residents were discharged to an inpatient psychiatric unit within the year before the study, and one-third of those residents experienced multiple admissions. Residents discharged to an inpatient unit were more likely to be young males with a history of homelessness and to have low motivation for participating in care. Individuals who return to inpatient care are an important concern. They represent a considerable demand on the service system, and their hospitalizations raise concerns about the effectiveness of psychiatric nursing facilities in preventing rehospitalization.

One factor influencing the use of mental health services was the refusal of services. Such refusal may be rudimentarily tied to past experiences. Although innovative treatment options and modes for service delivery continue to become available, they must be understood in the context of a consumer's prior experiences with service use. For example, one resident who refused services discussed a recent hospitalization: "They put me on a metal table with no sheets, no pillow, and they put restraints on me. They left me in an empty room. Across the hall was a woman screaming; she was dying. They told me they wouldn't let me go until the woman died. It was like I was dying inside. So I killed her." Another resident discussed her first hospitalization: "They strapped me down on a metal table. And that room … do you know what a hydro room is? People with mental illness shouldn't be treated like that."

Behavior is influenced by many factors aside from treatment effects, including knowledge about illness and treatment, the acceptability of treatment modalities, the influence of social support systems, and the stigma of mental illness. Change in service approaches must be preceded by research to identify the factors that act in concert to influence client outcomes.

Service refusal may be decreased by attention to individual patients' strengths and deficits in developing a treatment approach. An important step in services research would be the development and implementation of a tool that measures an individual's strengths in various areas of life, such as work, relationships, and hobbies. This type of information would help service providers develop treatment options that residents would be likely to use because the services would build on the positive areas of the individual's life while addressing deficits.

One final area to address is the low level of agreement between the SCID and chart diagnoses. The finding that many residents were misdiagnosed is not surprising. Research has documented that chart diagnoses are often incorrect (17). In light of the high rate of misdiagnosis in the study setting, the finding that medication management was the primary treatment is troubling. Although the appropriateness of psychotropic medications for individual residents' treatment was not evaluated, the clear potential for misuse of drugs exists when medications designed to treat schizophrenia are administered to persons who do not have this illness.

Conclusions

The deinstitutionalization movement envisioned a better future for people with mental illness. The transition from state hospitals to community services promised higher-quality care in more appropriate community-based facilities.

Intermediate nursing facilities have come to replace state hospitals as a pillar of the public mental health system in Illinois. Study participants' use of inpatient and outpatient mental health services suggests that few had ever received the types of services that might have helped them develop the capacity to live in noninstitutionalized settings. Furthermore, data from this study document continuing low levels of mental health services use beyond medication management for persons with the most severe psychiatric disorders.

For some residents, the intermediate nursing facility provided little more than a custodial environment in which few treatment services were offered, residents received inaccurate diagnoses, treatment that was provided was used by less needy residents, and residents were bounced back and forth between state hospitals and the nursing home. These adults were trapped in a new world of custodial care that depends on federal financing and private caregiving—a very different combination from earlier forms of institutional custodial care built on state financing and state caregiving.

Two issues need further consideration. The first is whether current custodial care derives from the nature of the illnesses or from the nature of the society in which we live (31). Second, recent social policy changes affecting nursing home care may partly reflect a trade-off between social and financial responsibilities. Socially, the service industry attempts to provide state-of-the-art services to persons with severe mental illness. Financially, the state's desire for continued federal reimbursement has stifled innovation in the development of community-based residential services for persons with mental illness. These two axes of social and financial responsibility affect care somewhat differently, but both can have a significant influence on policy.

Dr. Anderson is affiliated with the College of Public Health of the University of Iowa, 2700 Steindler Building, Iowa City, Iowa 52242 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Lewis is with the Institute for Policy Research at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of 78 residents with severe mental illness in an intermediate care facility in Illinois

|

Table 2. Variables associated with use of mental health services provided in an intermediate care facility and with discharge to psychiatric inpatient care

1. Grob GN: From Asylum to Community: Mental Health Policy in Modern America. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1991Google Scholar

2. Mechanic D, Aiken LH: Improving the care of patients with chronic mental illness. New England Journal of Medicine 317:1634-1638, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Richardson M: Mental health services: growth and development of a system, in Introduction to Health Services, 3rd ed. Edited by Williams SJ, Torrens PR. New York, Wiley, 1988Google Scholar

4. Mechanic D: The challenge of chronic mental illness: a retrospective and prospective view. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:891-896, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Olfson M, Glick ID, Mechanic D: Inpatient treatment of schizophrenia in general hospitals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:40-44, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Shadish WR, Bootzin RR: Long-term community care: mental health policy in the face of reality. Schizophrenia Bulletin 7:580-585, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Talbott JA: Deinstitutionalization: avoiding the disasters of the past. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 37:35-42, 1988Google Scholar

8. Mechanic D: Mental health services in the context of health insurance reform. Milbank Quarterly 71:349-364, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Bassuk EL, Gerson S: Deinstitutionalization and mental health services, in Mental Health Care and Social Policy. Edited by Brown P. Boston, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1985Google Scholar

10. Shadish WR, Silber BG, Bootzin RR: Mental patients in nursing homes: their characteristics and treatment. International Journal of Partial Hospitalization 2:153-163, 1984Medline, Google Scholar

11. Bootzin RR, Shadish WR, McSweeny AJ: Longitudinal outcomes of nursing home care for severely mentally ill patients. Journal of Social Issues 45:31-48, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Borson S, Liptzin B, Nininger J, et al: Psychiatry and the nursing home. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:1412-1418, 1987Link, Google Scholar

13. Burns DG, Smyer MA, Streit A: Mental health services for nursing home residents: what will it cost? Journal of Mental Health Administration 20:223-235, 1993Google Scholar

14. Shea DG, Streit A, Smyer MA: Determinants of the use of specialist mental health services by nursing home residents. Health Services Research 29:169-185, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

15. Bellack AS, Mueser KT: A comprehensive treatment program for schizophrenia and chronic mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 22:175-189, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Sherrell K, Anderson RL, Buckwalter K: Invisible residents: the chronically mentally ill elderly in nursing homes. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 12:131-139, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Lyons JS, Howard KI, O'Mahoney MT, et al: The Measurement and Management of Clinical Outcomes in Mental Health. New York, Wiley, 1997Google Scholar

18. Lyons JS, O'Mahoney MT, Miller SI, et al: Predicting readmission to the psychiatric hospital in a managed care environment: implications for quality indicators. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:337-340, 1997Link, Google Scholar

19. Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE: The MOS Short-Form General Health Survey: reliability and validity in a patient population. Medical Care 26:724-735, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

21. Steinberg M, Cicchetti D, Buchanan J, et al: Distinguishing between multiple personality disorder (dissociative identity disorder) and schizophrenia using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:495-502, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Blass JP: Mental status tests in geriatrics. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 33:461-462, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW: Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Maryland State Medical Journal 14:61-65, 1965Medline, Google Scholar

24. Mattes JA, Nayak D: Lithium versus fluphenazine for prophylaxis in mainly schizophrenic schizoaffectives. Biological Psychiatry 19:445-449, 1984Medline, Google Scholar

25. Levinson D, Levitt M: Schizoaffective mania reconsidered. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:415-425, 1987Link, Google Scholar

26. Kramer MS, Vogel WH, DiJohnson C, et al: Antidepressants in "depressed" schizophrenic inpatients. Archives of General Psychiatry 46:922-928, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Levinson D, Mowry BJ: Defining the schizophrenia spectrum: issues for genetic linkage studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin 17:491-514, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Warner R, Taylor D, Wright J, et al: Substance use among the mentally ill: prevalence, reasons for use, and effects on illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 64:30-39, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Mueser KT, Blanchard JJ, Bellack AS: Memory and social skill in schizophrenia: the role of gender. Psychiatry Research 57:141-153, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Penn DL, Mueser KT, Spaulding W: Information processing, social skill, and gender in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research 59:213-220, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Lewis DA, Riger S, Rosenberg H, et al: Worlds of the Mentally Ill: How Deinstitutionalization Works in the City. Carbondale, Ill, Southern Illinois University Press, 1991Google Scholar