Program Closure and Change Among VA Substance Abuse Treatment Programs

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The population of Veterans Affairs (VA) substance abuse treatment programs in 1990 and 1994 was examined to determine which factors—program legitimacy or cost—accounted for program closure and change. Legitimacy is a concept in institutional theory that organizations tend to take on a form appropriate to the environment. METHODS: The study had two competing hypotheses. The first was that if external pressures push programs to produce high-quality and efficient treatment, then those that are initially closer to the legitimate form should be less likely to close later, and among surviving programs they should be less likely to experience change. The second hypothesis was that cost is the primary factor in program closure and change. The study used data from administrative surveys of all VA programs (273 in 1990 and 389 in 1994). Program legitimacy variables measured whether programs offered the prevalent type of treatment, such as 12-step groups or behavioral treatment, and had the prevalent type of staff. RESULTS: Program costs did not explain closure or change. For inpatient programs, the risk of closure increased in facilities with more than one substance abuse treatment program. The risk of closure increased for outpatient programs offering the prevalent type of treatment, contrary to what was predicted by the legitimacy hypothesis. Inpatient programs that offered the prevalent treatment were less likely to change the type of treatment offered. CONCLUSIONS: Patterns of change differed over time for inpatient and outpatient programs. Legitimacy factors, rather than cost, seem to play a role in program closure and change, although the picture is clearer for inpatient programs than for outpatient programs.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), like other branches of the government, is under increasing pressure to reduce costs (1). However, veterans remain a highly valued political constituency, demanding high-quality health care, including substance abuse treatment (2,3). Thus VA has been seeking to provide high-quality services to veterans while at the same time cutting costs and eliminating wasted resources involved in providing these services.

This situation creates competing pressures on VA to maintain legitimacy as a treatment service provider while becoming more efficient by streamlining services (4,5,6,7). The study reported here, based on an unpublished doctoral dissertation (8), examined whether factors related to legitimacy or cost drive changes in the organization of VA substance abuse treatment programs.

The institutional theory of organizational environments suggests that organizations tend to take on a form appropriate to the environment. Adopting this form tends to legitimatize organizations within their environments (9,10,11). Consequently, programs that are closer to the legitimate form at an initial point in time should be less likely to close later, and among survivors, these programs should be less likely to experience change.

This study had two competing hypotheses. One was that VA programs are pushed toward the legitimate form as a result of external pressure to produce both high-quality and more streamlined treatment, as well as uncertainty about how to achieve these outcomes. The second hypothesis was that cost is the primary concern of administrators, and that programs that are more expensive to operate, regardless of quality, are at greater risk of closure and, if they survive, are more likely to be pushed into line with programs of similar cost.

For this analysis, the most prevalent types of treatment and staffing patterns were defined as the legitimate form. Prevalence indicates that programs may be imitating each other as a way of dealing with uncertainty in the environment (12,13).

Methods

Data

Data were derived from two surveys of coordinators of VA substance abuse treatment programs: the Drug and Alcohol Program Structure Inventory (DAPSI) (14) and the Drug and Alcohol Program Survey (DAPS) (15). DAPSI obtained organizational data on the population of 273 VA substance abuse treatment programs for fiscal year 1990. DAPS gathered organizational data on the population of 389 VA substance abuse treatment programs for fiscal year 1994, including 223 programs assessed previously in 1990. In fiscal year 1994, a total of 166 new programs existed that did not exist in fiscal year 1990.

Both surveys were administered by the VA Program Evaluation and Resource Center. All surveys were completed and returned, for a 100 percent completion rate. In this report, inpatient and outpatient programs are examined separately.

Program closure and change

To test the competing hypotheses, three dichotomous variables were examined for fiscal years 1990 and 1994. The first was program closure, measured as either closure or survival of a program from fiscal year 1990 to fiscal year 1994. Program change was measured by two dichotomous variables, staff cuts and change in treatment type. Staff cuts in fiscal year 1994 measured whether a program received any cuts in the past year. Change in treatment type from fiscal year 1990 to fiscal year 1994 measured whether programs provided different types of treatment over time.

Treatment types

The types of treatment measured in inpatient and outpatient programs were 12-step groups, behavioral treatment, and training in daily living skills. Behavioral treatment consisted of social skills training, stress management training, and recreational therapy. Daily living skills training consisted of family therapy and vocational rehabilitation therapy. In some cases, combinations of the dominant types emerged, such as 12-step programs with behavioral elements. In some programs, no single treatment type dominated, and the programs were low in all three dimensions, which may have indicated the lack of a dominant treatment philosophy. Some outpatient programs also offered methadone maintenance, which was considered a fourth type of treatment. If a program changed from an inpatient to an outpatient format, it was considered a program closure in 1990 and a new program in 1994.

The type of treatment was assessed by converting several continuous measures of treatment services into dichotomous variables and then identifying patterns of responses across dimensions (16). Treatment services were initially assessed by the percentage of patients involved in relevant treatment activities.

Staff types

Program staff were categorized as doctoral-level staff, nursing staff, and daily living staff. Doctoral-level staff included physicians, psychiatrists, and doctoral-level psychologists. Nursing staff consisted of registered nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, licensed vocational nurses, and licensed practical nurses. Daily living staff consisted of addiction counselors, vocational counselors, and social workers. Consistent with the identification of treatment types, staff types were created based on patterns of available staff members within each program.

Enhancement funding

Congress provided $60 million for enhancement and expansion of VA substance abuse treatment programs in 1990 and an additional $15 million over the prior year's allocation in each subsequent year from 1991 to 1993. This money was to be used to develop new programs and increase staffing and treatment resources (14). Receipt of enhancement funds represents a form of legitimization of the program by demonstrating its adherence to a known environmental goal.

Program coordinator characteristics

Two other independent variables assessed characteristics of the program coordinator. The first, program coordinator status, was treated as an indicator of legitimacy, given that a program coordinator should have a strong impact on the form the program takes and how legitimate it appears within the facility (10). A dichotomous variable was created for whether or not the program coordinator held a doctoral-level degree.

The second dichotomous independent variable was the relative position of a program coordinator, or whether a coordinator was responsible for coordinating program activities only or was also a director of services related to substance abuse treatment. The latter role indicates a higher and, presumably, more powerful position.

Staff costs

Costs of staff represent the main alternative to legitimacy factors as an explanation for program closure and change. It was assumed that other facility-level costs were constant across sites and that staff costs accounted for most of the variation in program cost. Staff costs were measured as the number of staff, by position, multiplied by the average national salary for that position. The total costs of all staff for each program were calculated. Costs of administrative or secretarial staff were not included.

Costs of treatment staff at each facility based on national averages were maintained by VA through centralized accounting for the local management file and the cost distribution report. Cost totals for fiscal year 1990 were adjusted to fiscal year 1994 dollars. Fiscal year 1990 salary dollars were adjusted to fiscal year 1994 dollars using the Consumer Price Index for Urban Consumers. The 1990 index was 130.7, and the 1994 index was 148.2. Dividing 148.2 by 130.7 yields an adjustment term of 1.13, or approximately a 13 percent wage adjustment. Staff cost data were transformed with a natural logarithmic transformation (17).

Results

Separate logistic regressions for inpatient and outpatient programs were tested. Because the results are estimated in log odds, the interpretation of the effect is in the form of odds ratios (18). For log total staff cost, the only continuous variable, the odds ratio is not given because of inflated values, due to the log transformation of a logged variable (19). (In a separate analysis, region of the country where the facility was located was not found to be related to any outcomes for inpatient or outpatient programs.)

Basic program characteristics

A total of 273 VA substance abuse treatment programs were operating in fiscal year 1990, of which 59 did not survive to fiscal year 1994. Thirty-eight were inpatient programs, and 21 were outpatient programs. Of the 38 closed inpatient programs, four changed treatment format and became outpatient-only programs by 1994. These programs were treated as closures in 1990 and new programs in 1994, as were five of the 21 outpatient programs closed in 1990 that began providing inpatient treatment by 1994.

Most other surviving inpatient programs made no changes in treatment setting, although 22 percent added outpatient services to their inpatient format, and 12 percent dropped outpatient services.

Staff costs

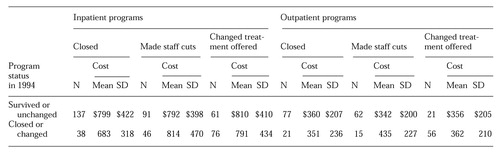

Table 1 shows staff costs for fiscal year 1994 for programs that survived or that did not change the type of treatment offered between 1990 and 1994 and for those that closed or that changed treatment type. It also shows staff costs for the programs in both groups that made staff cuts. No statistically significant differences in staff costs were found between any of these programs—that is, between those that closed, those that changed treatment type, or those that made staff cuts. This finding held for both inpatient and outpatient programs.

Closed programs tended to be less costly than surviving programs, and programs that made staff cuts tended to be more costly, although the differences were not statistically significant. These findings suggest that costs alone cannot account for organizational change and point to a more complex strategy by decision makers determining organizational structure.

Inpatient programs

In fiscal year 1990, a total of 175 VA inpatient substance abuse treatment programs were operating. Of those programs, 137 (78 percent) survived, and 38 (22 percent) closed. Thirty-four percent of the 137 surviving programs made staff cuts, and most (56 percent) changed the type of treatment provided.

Among inpatient programs, a trend was noted for more of the surviving programs to have received enhancement funding compared with the programs that closed, although the difference was not statistically significant. No other differences between the closed and surviving inpatient programs were significant, and the multivariate analysis did not yield predictors of programs that closed or survived.

An additional model was tested in an effort to explain program closure among the inpatient programs, using a dichotomous variable indicating whether the program was the only inpatient substance abuse treatment program at that VA facility. This model was based on the rationale that eliminating inpatient substance abuse treatment programs is a cost-saving measure but that removing all such programs from a facility threatens legitimacy, because no inpatient services would be provided for a serious health problem among veterans. By allowing at least one program to survive, both cost savings and legitimacy concerns might be satisfied.

The results from the logistic regression model indicated that lone programs within a facility were significantly less likely to close. Being a lone program reduced the likelihood of program closure by a third (coefficient=-.53, SE=.19, odds ratio=.35, p<.01; model χ2=7.92, df=1, p<.01; R2=.04, N=175).

No significant differences were noted between inpatient programs that made staff cuts and those that did not. The logistic regression analysis did not yield any predictors of which inpatient programs made staff cuts and which did not.

Inpatient programs that offered 12-step groups with behavioral elements in 1990 were significantly less likely in 1994 to have changed treatment type than programs that offered other types of treatment in 1990. Seventy-four percent of the inpatient programs that remained unchanged offered 12-step groups, compared with 29 percent of programs that changed (χ2=27.2, df=1, p<.01).

This finding held for the logistic regression analysis. Programs that offered 12-step groups with behavioral elements were significantly less likely to change treatment type; the likelihood of change was reduced by a tenth. The overall model was significant, explaining 17 percent of the variance in treatment type change (coefficient=-1.09, SE=.22, OR=.11, p<.01; model χ2=31.65, df=6, p<.01; R2=.17, N=137).

Outpatient programs

In fiscal year 1990, a total of 98 VA outpatient substance abuse treatment programs were operating. Of that number, 77 (79 percent) survived, and 21 (21 percent) closed. Nearly 20 percent of surviving programs made staff cuts. Seventy-three percent of programs changed the type of treatment offered.

Bivariate comparisons indicated that outpatient programs that closed were significantly more likely to have program coordinators who held doctoral degrees and were significantly more likely to offer the most prevalent type of treatment, 12-step groups. Eighty percent of outpatient programs that closed had program coordinators with doctoral degrees, compared with 45 percent of the surviving programs (χ2=7.3, df=1, p<.01). Sixty-seven percent of closed outpatient programs offered 12-step groups, compared with 33 percent of surviving programs (χ2=8.1, df=1, p<.01).

Results of logistic regression analysis confirmed those findings. Programs in which the coordinator held a doctoral degree were more than six times more likely to close than those in which the coordinator did not have a doctoral degree (coefficient=.92, SE=.36, OR=6.36, p<.01; model χ2=20.99, df=6, p<.01; R2=.21, N=98). Moreover, programs offering the prevalent treatment type were nearly six times more likely to close than those offering other types of treatment. The overall model was significant and explained 21 percent of the variance (coefficient=.88, SE=0.30, OR=5.79, p<.01; model χ2=20.99, df=6, p<.01; R2=.21, N=98).

The finding that outpatient programs offering the prevalent treatment type were more likely to close might be explained by a shift toward other treatment philosophies, specifically, treatment low on all dimensions. In a separate analysis, programs offering treatment low on all dimensions were less likely to close, although the finding was not significant in the multivariate model. A program that measures low on all dimensions may provide care that is customized to individual patients, rather than having an overarching treatment philosophy applied to all patients. This explanation is consistent with VA's goal of matching treatment to the needs of patients.

The finding that outpatient programs in which the program director held a doctoral degree were significantly more likely to close might relate to a cost variable rather than, or in addition to, a legitimacy variable, as staff at this level earn substantially more than other staff.

No significant differences across predictors were found between outpatient programs that made staff cuts and those that did not. The logistic regression analysis did not yield predictors of which outpatient programs made staff cuts and which did not.

Outpatient programs with coordinators who held a doctoral degree were less likely to change treatment type. Sixty-two percent of the programs that did not change treatment type had a program coordinator with a doctoral degree, compared with 36 percent of programs that did change treatment type (χ2=4.3, df=1, p<.05).

This finding was supported by a trend found in the logistic regression analysis, although the effect was not statistically significant. No other predictors of which outpatient programs changed treatment type were statistically significant.

The trend toward a change in treatment type in outpatient programs with a coordinator who held a doctoral degree is contrary to the finding of a higher likelihood of closure among programs in which the coordinator held a doctoral degree. The results suggest a possible cost-related effect on program closure and a legitimacy-related effect on program change.

Discussion and conclusions

For both inpatient and outpatient substance abuse treatment programs, staff costs were not related to closure, staff cuts, or change in treatment type, and the cost differences between surviving programs and those that closed or changed were small. Closed programs were actually less expensive than surviving programs. Legitimacy is but one possible alternative explanation.

For inpatient programs, closure was associated with having more than one program at a single VA facility, suggesting a combination of cost and legitimacy factors. At these facilities the number of programs could be reduced in order to lower costs as long as at least one program remained open for purposes of legitimacy. Program change was associated with initially offering treatment other than the prevalent type, 12-step groups with behavioral elements. Again, legitimacy seems to play a role here because programs that adhered to the legitimate form were more likely to retain their form over time.

For outpatient programs, closure was associated with offering the prevalent treatment (12-step groups) and having a program coordinator with a doctoral degree.

VA guidelines for substance abuse treatment during this time period were to offer more individualized treatment of no dominant type. A trend was noted for programs that adopted the guidelines to be less likely to close. Although more evidence is needed to determine whether the programs offering undifferentiated treatment types are in fact offering individualized treatment, the results suggest that outpatient programs might be changing in the direction of a new legitimate form.

Programs that had program coordinators with a doctoral-level degree also had an increased risk of closure. Doctoral-level staff substantially increase program cost. However, they may also provide greater legitimacy for the program. The legitimacy would be more in the eyes of VA administrators than of clientele; clients in programs based on the 12-step approach typically interact with staff members who are in recovery, and coordinators with higher-level degrees are probably less likely than other coordinators to be in recovery themselves.

Modeling change within VA

The findings provided support for the legitimacy hypothesis, which holds that programs are pushed toward the legitimate form by external pressures to produce both high-quality and more streamlined treatment, as well as by uncertainty about how to achieve these outcomes. A trend was found for inpatient programs to have been influenced by these external pressures, while outpatient programs appear to have been influenced by both cost and legitimacy factors.

Change within VA is certainly occurring; however, modeling the change is more complex than looking strictly at costs, which is made clear by the fact that the staff cuts made in inpatient and outpatient programs could not be attributed to the sole aim of reducing costs.

One reason for the complexity in predicting change among programs is that the models attempted to uniformly predict decisions made by facility directors. Personal characteristics, such as their beliefs about the effectiveness of substance abuse treatment, may play a substantial role in their decisions. Likewise, political considerations, such as the quality of relationships between facility directors and program coordinators, also may be important determinants.

Another point to consider is that program changes may have been implemented to save programs from closure. Programs that were able to avoid closure may have possessed an ability to cope with organizational changes. Unfortunately, data were unavailable to test this hypothesis, because these factors and others related to administrative decision making could not be addressed in the secondary analyses of the data reported here.

To adequately model change within VA, which has a structure strongly determined by administrative decisions, more information about the guidelines under which the decisions are made is also required. The analysis of inpatient program closures hints at an answer, because program closure was related to having more than one program at a facility. This finding suggests that both cost and legitimacy concerns are at work. It also suggests that unmeasured or idiosyncratic factors at the local level, such as decisions made by facility directors, may be the most important factors.

Future directions

Further research is needed on existing programs, because the period examined here captured only the beginning of a downsizing trend. Measurement at a third time point would allow determination of whether these treatment programs adapted further. New programs could also be examined, providing a clearer application of institutional theory to this administrative structure. In addition, more information on the decision-making processes of facility directors should be gathered to help make sense of the organizational changes taking place in these treatment programs.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks John Finney, Ph.D., Ann Hironaka, Ph.D., Norman Hoffmann, Ph.D., Keith Humphreys, Ph.D., Evan Schofer, Ph.D., and Susie Wu, M.Ed., for their helpful suggestions. Support for this research was provided through fellowships from the department of health research and policy at Stanford University and the department of health services research and development at the VA Palo Alto Health Care System.

Dr. Floyd is affiliated with the Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies at Brown University, Box G-BH, Providence, Rhode Island 02912 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Mean staff costs (in thousands of dollars) in 1990 for the 273 substance abuse treatment programs in the Veterans affairs health system, by whether they survived, closed, changed, or remained unchanged between 1990 and 1994

1. Department of Veterans Affairs Performance Agreement. Washington, DC, White House and Department of Veterans Affairs, 1994Google Scholar

2. Alcohol Dependency: Are Veterans Getting the Health Care They Need? Hearing Before the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, 102nd Congress, 1st session, Apr 18, 1991Google Scholar

3. VA Health Care: Alcoholism Screening Procedures Should Be Improved. Washington, DC, General Accounting Office, 1991Google Scholar

4. Suchman MC: Managing legitimacy: strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review 20:571-610, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

5. D'Aunno T, Sutton RI, Price RH: Isomorphism and external support in conflicting institutional environments: a study of drug abuse treatment units. Academy of Management Journal 34:636-661, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Alexander JA, D'Aunno TA, Succi MJ: Determinants of profound organizational change: choice of conversion or closure among rural hospitals. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 37:238-251, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Leavitt HJ, Dill WR, Eyring HB: Strategies for survival: how organizations cope with their worlds, in Readings in Managerial Psychology, 4th ed. Edited by Leavitt HJ, Pondy LR, Boje DM. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1989Google Scholar

8. Floyd AS: Changes in the Organization of VA Substance Abuse Treatment Programs: An Institutional Analysis. Doctoral dissertation. Palo Alto, Calif, Stanford University, Department of Sociology, 1997Google Scholar

9. Meyer JW, Rowan B: Institutional organizations: formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology 83:340-363, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Scott WR: Organizations: Rational, Natural, and Open Systems, 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice Hall, 1992Google Scholar

11. DiMaggio PJ, Powell WW: The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective reality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review 48:147-160, 1983Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Scott WR: Institutions and Organizations. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1995Google Scholar

13. Meyer JW: Institutional and organizational rationalization in the mental health system, in Institutional Environments and Organizations: Structural Complexity and Individualism. Edited by Scott WR, Meyer JW. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage, 1994Google Scholar

14. Peterson KA, Swindle RW, Moos RH, et al: New directions in substance abuse services: programmatic innovations in the Veterans Administration. Journal of Mental Health Administration 19:41-52, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Humphreys K, Hamilton EG, Moos RH, et al: Policy-relevant program evaluation in a national substance abuse treatment system. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:373-385, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

16. Dillon WR, Goldstein M: Multivariate Analysis: Methods and Applications. New York, Wiley, 1984Google Scholar

17. Blalock HM: Social Statistics, 2nd ed, rev. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1979Google Scholar

18. Knoke D, Bohrnstedt GW: Statistics for Social Data Analysis, 3rd ed. Itasca, Ill, Peacock, 1994Google Scholar

19. JMP Statistics and Graphics Guide, Version 3.1. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, Inc, 1995Google Scholar