Economic Grand Rounds: Direct Cost of Care for Patients With Schizophrenia Treated With Haloperidol in an Emergency Unit

A 1991 study estimated that some 250,000 Canadians suffered from schizophrenia and that at least 105,000 adults were currently being treated for this illness (1). In recent years, the emphasis in schizophrenia management has shifted from long-term inpatient care to community-based resources. Because both family members and community providers have been unprepared to offer care for patients with schizophrenia, the number of these patients presenting in hospital emergency units has increased.

Haloperidol has been widely used to treat patients admitted to emergency units who are experiencing exacerbation of the symptoms of schizophrenia. To assess the cost impact of using new drugs in our emergency department, we were interested in determining baseline costs of treating patients with haloperidol. To this end, we reviewed current resource utilization in the department.

Methods

The study was conducted in the emergency department of the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal. The records of psychiatric patients who came to the emergency department between April 22 and September 17, 1996, were extracted from emergency room and hospital records. Patients with a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia who were treated with oral haloperidol (N=19) or injectable haloperidol (N=1) were included in the analysis. Because the study was retrospective, physicians and other health professionals were unaware of our analysis, and thus neither treatment modalities nor the practices of professionals were influenced.

The study sought to determine the proportion of patients with schizophrenia who were treated with haloperidol and the mean cost of an emergency room stay for these patients. The patients were followed from the time of their arrival in the emergency unit until their discharge from the unit or hospital. Only costs of care provided in the emergency unit were calculated.

A psychiatric nurse was trained to use a questionnaire to collect patient data from the charts. Information collected included age, gender, principal diagnosis, length of stay in the emergency department, medications prescribed and quantity administered, and the number of visits from general practitioners, psychiatrists, psychiatry residents, and nurses.

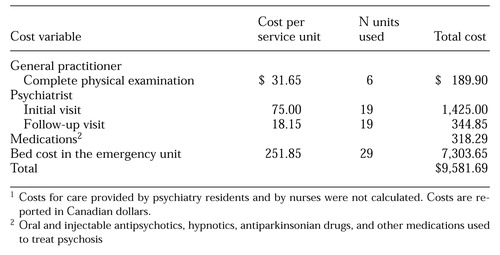

Data on resources used were obtained from the emergency unit and hospital records. Cost data came from the May 1996 editions of the General Practitioners' Manual and the Medical Specialists' Manual of the Health Insurance Plan of Quebec. A visit by a general practitioner, which included a complete physical examination, was $31.65. A visit by the psychiatrist was $75, and a follow-up psychiatric visit was $18.15.

Costs for oral and injectable antipsychotics, hypnotics, antiparkinsonian drugs, and other medications used to treat psychosis were calculated.

The daily bed cost in the emergency unit was calculated. One day was defined as at least an eight-hour stay; bed costs were not added for stays less than eight hours.

The total cost of care in the emergency unit was calculated based on bed cost, costs for services provided by physicians and psychiatrists, and costs of medications. Not included were costs for interventions by psychiatric residents and nurses, because their time with patients was not reported in the medical records. Indirect costs also were not included.

Results

Of the 257 psychiatric patients who visited the emergency unit over the five-month study period, 56 (22 percent) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Of the 56 patients, 20 (36 percent) received haloperidol as a treatment, 11 (20 percent) received another antipsychotic, and 25 (45 percent) received no medication.

Among the 20 patients treated with haloperidol, 23 admissions to the emergency unit were noted. Of the 20 patients, 18 (90 percent) were men. The mean±SD age of the 20 patients was 46±12 years (range=23 to 74 years), with no significant difference between men and women. The mean±SD length of stay in the emergency unit of the haloperidol-treated patients was 25±23 hours (17±12 hours for men and 54±29 hours for women). Half of the patients treated with haloperidol stayed for less than 17 hours, and three stayed for two hours. The mean length of stay for the haloperidol-treated patients tended to increase with age, although the differences between age groups were not statistically significant. A total of 205 nurse interventions were recorded for the 20 patients, although, as noted, costs for these services were not included in the total cost.

Only three of the haloperidol-treated patients (15 percent) were transferred to the hospital, for 29, 36, and 50 days. Whether they were returned home or were institutionalized remains unknown because this information was not documented in the medical records.

As Table 1 shows, six of the patients received a complete physical examination by a general practitioner, and 19 had both a consultation and a follow-up visit with a psychiatrist. The mean daily bed cost in the emergency unit was $251.65 per day; the total cost for the 20 patients included charges for 29 days. The mean±SD cost for the 20 haloperidol-treated patients was $416.60 per emergency visit. The total cost of medications for these patients was $318.29.

Discussion and conclusions

This retrospective study identified health care resources used by patients in our emergency unit who were experiencing schizophrenic relapses and were treated with haloperidol.

By using medical records, it was possible to evaluate the costs of medication, the daily cost of an emergency stay, and the fees for general practitioners and psychiatrists. Because the psychiatry residents and nurses receive a fixed annual wage, the time they spent with each patient was not documented. However, because time spent caring for patients with acute exacerbation of symptoms of schizophrenia is a major cost factor, it would be useful to obtain this information. One way to do so would be to conduct a time-and-motion study. Data on the amount of time each nurse and resident spend with each patient would provide a better understanding of the pattern of care provided to this patient group in an emergency setting.

The study demonstrated that it is possible to consult medical records to assess most costs, and that a complete and expensive prospective study is not necessary. Costs not documented in medical records can be assessed using a questionnaire or prospective methods. However, in a prospective study it is important to ensure that professionals provide the same types and amounts of care and do not modify their practices as a result of being observed.

Because of the small sample size, it was not relevant to adjust for variables such as disposition of patients after treatment, noncompliance, level of education, presence of a caregiver, socioeconomic status, and urban or rural residence. Information on most of these variables was not reported in the medical records. However, they could have affected the study results.

Aside from the basic cost of an emergency stay, services delivered by psychiatrists represented a major cost factor. Psychiatrists remained the most costly resource utilized. Nursing services, such as patient monitoring, recording of progress notes, and administration of medication, may have accounted for more of the resources utilized, but nursing services provided were not translated into monetary values.

The results of this study represent a starting point. More research is needed to better understand resource utilization in an emergency setting for patients with schizophrenia who are experiencing relapses. Costs for resident and nursing care should be added to the model. The model could be refined to account for differences in practice patterns and to determine direct costs of resources used in other emergency units. Calculating indirect costs, such as the social consequences of symptom exacerbation, would add another dimension to the model. Future studies should also compare costs for patients treated with oral or injectable haloperidol or for those treated with other antipsychotics and with any new drugs that may be developed.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Yvonne Hindle, R.N., for assistance with data collection.

When this work was done, Ms. Ricard was affiliated with the health economics department of Hoechst Marion Roussel Canada Research Inc., where Mr. Lauriol is currently affiliated. Ms. Ricard is now with Biocapital, a biotechnology venture capital firm in Montreal. Ms. Bélanger and Dr. Chouinard are with the clinical psychopharmacology unit of the Allan Memorial Institute at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal. Dr. Chouinard is also with the department of psychiatry at the University of Montreal. Send correspondence to Ms. Ricard at Biocapital, 3690 Rue de la Montaigne, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H3G288 (e-mail, [email protected]). Steven S. Sharfstein, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Use of health care resources by 20 patients with schizophrenia treated with haloperidol in a hospital emergency unit1

1. Schizophrenia: A Handbook for Families. Ottawa, Health Canada and the Schizophrenia Society of Canada, 1991Google Scholar