Managed Care: Public-Sector Managed Behavioral Health Care: II. Contracting for Medicaid Services-the Massachusetts Experience

The quality of care for patients and families with mental health and substance abuse disorders in the United States depends in large measure on the quality of the contracting process between government and corporate health care purchasers and the insurance intermediaries that oversee and pay for care. Contracts and the financing mechanisms they establish do not ensure quality. But as the premier authorities on the contracting process state, they "influence conduct directly and indirectly and thus represent two of the health care system's most powerful drivers" (1).

Americans are clearly worried about whether they can trust managed care organizations to take good care of them. When a recent nationwide survey asked a random sample of adults if they were "worried that your health plan would be more concerned about saving money than about [providing] the best treatment for you if you are sick," 61 percent enrolled in heavily managed care plans but only 34 percent of those in traditional plans said they were somewhat or very worried (2). Although 72 percent of the sample agreed that money saved through managed care "helps health insurance companies to earn more profits," only 49 percent believed that that the money saved also "makes health care more affordable for people like you."

Federal law governing Medicaid states that services must be "sufficient in amount, duration and scope to reasonably achieve their purpose" (1). However, the law is silent about which purposes or clinical objectives must be included. Most contracts require medically necessary treatment, but the term "medical necessity" has no fixed meaning (3). As a result, public-sector clients and the clinicians who serve them must look to the contracting process to specify the expectations and values that will shape the goals of managed behavioral health care programs.

The Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law has proposed useful model contract language for defining medically necessary services in public systems (4). However, public purchasers are still early in the learning curve about how to use contracts to promote high-quality managed behavioral health care services. This column, the second in a series on public-sector managed care (5), uses the contracting process between the Massachusetts Division of Medical Assistance, which is the state Medicaid agency, and Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership, the state's carve-out insurance provider since July 1996, to contribute to the learning curve. Future columns will focus on other aspects of the contracting process and the experiences of other states.

The Massachusetts situation

Massachusetts has had the nation's first—since 1992—and largest Medicaid behavioral health care carve-out contract, with approximately 400,000 recipients. Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership, a for-profit company, is owned by ValueOptions, the largest provider of Medicaid behavioral health care carve-out services, with 3.7 million "covered lives" in Medicaid contracts; it is the second largest managed behavioral health care company overall, with 20 million covered lives (6).

The Massachusetts Division of Medical Assistance applies an activist philosophy of health care purchasing. According to the division's commissioner, Bruce Bullen (7), "The prudent purchaser is not a passive buyer who merely selects the best value from among the choices offered [but one] who has a vision of what health care can—and should—be, and who … drives the marketplace towards objectives that the purchaser sets." To conduct this kind of activism, Mr. Bullen has written, the purchaser must define quality and "express those definitions in purchasing specifications and work with contractors to meet them."

These are fine words and noble sentiments. But given public distrust of managed care, especially of for-profit managed care, how can recipients of Medicaid-supported behavioral health services and the citizens of Massachusetts possibly trust a for-profit entity such as Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership—whose owner, ValueOptions, is a for-profit entity—to deliver the best possible care to the eligible population within the budget provided by the state?

Alan Stone (8), past-president of the American Psychiatric Association and trenchant critic of managed care, provides a clue to the preconditions for trust: "Until the economic incentives to cut care are eliminated, the ethics of saving the commons is self-interest masquerading as distributive justice." Guided by Stone's precept about incentives to cut care—and by the advice Watergate's "Deep Throat" gave to reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein—to "follow the money"—we approached this study of the contracting process between the Division of Medical Assistance and Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership by asking how the carve-out insurance provider makes its money.

Using financial incentives to "walk the talk"

When the public believes that managed care programs talk about quality but care primarily about cost, it reacts with cynicism and anger (9). Experience with the Oregon Health Plan, however, suggests that the public is prepared to understand and accept hard choices and even explicit rationing if it understands that the process is necessary and is being conducted openly and fairly (10).

In the first negotiations between the Division of Medical Assistance and Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership, the parties were in conflict over two questions. First, how could the state ensure high-quality care for Medicaid recipients? Second, how could Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership make a reasonable return at the same time? The best answer the parties were able to come up with was to tie earnings to performance standards. In retrospect it appears that the parties may have developed a win-win approach.

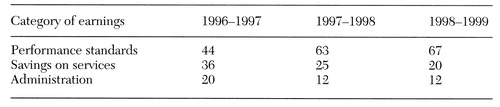

With each year of the contract, progressively more of Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership's potential for profit has been attached to performance standards and progressively less to savings on services, as Table 1 shows. In 1996-1997, the first year of the contract, $5.3 million of the Partnership's earnings came from meeting performance standards and administrative targets, while only $250,000 came from spending less for services than was budgeted by the Division of Medical Assistance. All of the earnings from savings on services came from one subcontract with the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health and represented no savings on Medicaid. Preliminary figures for 1997-1998 suggest a similar outcome.

The 1997-1998 contract set 22 performance standards. The standards focused on aftercare planning for hospitalized patients, involvement of family members and guardians in planning for children and adolescents, medication monitoring, readmission rates, availability of crisis intervention and intensive case management services, and other clinically important measures. A visitor to the offices of the Partnership sees the performance targets posted on virtually every wall. Interviews with major service providers in the Partnership network reveals that providers are well aware of the standards. The standards are clearly part of a process designed to transform "talk" about quality into the "walk" of performance.

Performance standards are not the sole means through which the state defines its objectives. The body of the contract between the Division of Medical Assistance and the Partnership creates numerous requirements. Performance standards, however, highlight issues the purchaser regards as especially important. They contribute to creation of a culture of expectations about the values that should govern provision of care to Medicaid recipients. They give the purchaser, the managed behavioral health care company, clients, families, and providers of service the potential for speaking the same language in setting goals and evaluating outcomes.

The issue of public participation in shaping health care policy and health institutions is important enough to have launched a new international journal, Health Expectations (11). In the Massachusetts experience, the state has attempted to involve key stakeholders through an advisory process conducted at multiple public forums. Major stakeholders, including service users, the Alliance for the Mentally Ill and other advocacy groups, state officials from other departments, service providers, academic researchers, and others, have participated in setting the standards. The state perceives the quantity and quality of public input as having increased steadily over the three years of the contracting process (Ansorge-Ball L, Massachusetts Division of Medical Assistance, personal communication, Sept 29, 1998).

Conclusions

Showing that incentives are aligned with central clinical goals and that earnings correlate with achieving performance targets, not with withholding services, does not in itself prove that Massachusetts is purchasing wisely or that Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership is performing optimally. The carve-out insurance provider is not without its critics (12). The ultimate criterion for assessing a program is the health improvement for individual clients and the degree of morbidity reduction in the insured population (13). Determining whether that criterion has been satisfied, however, requires data that few locales—including Massachusetts—have obtained.

In the absence of definitive outcome data, programs that can show that their clinical policies reflect a sincere effort to provide the best possible care to individuals within the constraints of the budget for the population should and will receive more trust. By this latter criterion, the contracting process between the Massachusetts Division of Medical Assistance and Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership has much to teach. By focusing on performance standards and involving the public in the design of these standards, the contracting process establishes a creative approach to "accountability for reasonableness," which we have elsewhere argued is an essential element in establishing the legitimacy of managed care (14).

In a decade marked by a dearth of public leadership on the very concept of ethical managed care (15), we believe that the ongoing contracting process established by Massachusetts and its carve-out vendor provides an example of how the contracting process can be used to articulate and pursue a vision of excellent health care for a population within a budget. By law, public-sector managed behavioral health programs are more accountable to the public they serve than are private-sector programs. As experience accumulates, public programs may be able to teach crucial lessons about legitimacy and fair process to the entire "industry" (16).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Laurie Ansorge-Ball, Bruce Bullen, Nancy Lane, and Richard Sheola for help in learning about the Massachusetts contracting process; Eric Goplerud and Stephen A. Somers for help in learning about national issues in public purchasing; and the Greenwall Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Medicaid Managed Care Program, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration for their support.

Dr. Sabin, who is editor of this column, is associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and codirector of the Center for Ethics in Managed Care at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care and Harvard Medical School. Dr. Daniels is Goldthwaite professor in the department of philosophy at Tufts University in Boston and professor of medical ethics in the department of social medicine at Tufts Medical School. Address correspondence to Dr. Sabin at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Teaching Programs, 126 Brookline Avenue, Suite 200, Boston, Massachusetts 02215 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Percentage distribution of categories of earnings in the first three years of the contract for Medicaid mental health and substance abuse services between the Massachusetts Division of Medical Assistance and Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership

1. Rosenbaum S, Silver K, Wehr E: An Evaluation of Contracts Between State Medicaid Agencies and Managed Care Organizations for the Prevention and Treatment of Mental Illness and Substance Abuse Disorders. Report Prepared for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Managed Care Technical Assistance Series. Washington, DC, Center for Health Policy Research, George Washington University, Aug 1997Google Scholar

2. Blendon RJ, Brodie M, Benson JM, et al: Understanding the managed care backlash. Health Affairs 17(4):80-94, 1998Google Scholar

3. Sabin JE, Daniels N: Determining "medical necessity" in mental health practice. Hastings Center Report 24(6):5-13, 1994Google Scholar

4. Defining "Medically Necessary" Services to Protect Plan Members. Washington, DC, Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, March 1997Google Scholar

5. Sabin JE: Public-sector managed behavioral health care: I. developing an effective case management program. Psychiatric Services 49:31-33, 1998Link, Google Scholar

6. ValueOptions hybrid emerges as FHC completes acquisition. Mental Health Weekly 8(25):1,4, 1998Google Scholar

7. Bullen B: What Is a Prudent Purchaser? Washington, DC, National Association of State Medicaid Directors, 1998Google Scholar

8. Stone AA: Managed care: the iceberg and the Titanic. Harvard Mental Health Letter 15(1):4-6, 1998Google Scholar

9. Chang CF, Kiser LJ, Bailey JE, et al: Tennessee's failed managed care program for mental health and substance abuse services. JAMA 279:864-869, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Sabin JE, Daniels N: Setting behavioral health priorities: good news and crucial lessons from the Oregon Health Plan. Psychiatric Services 48:469-470,482, 1997Link, Google Scholar

11. Coulter A: Welcome to the inaugural issue. Health Expectations: an International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy 1:1-2, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Massachusetts mental health advocates cite problems in Medicaid managed care program. Psychiatric Services 48:1215, 1997Link, Google Scholar

13. Sabin JE: What should we advocate for in for-profit mental health care, and how should we do it? Psychiatric Services 47:1061-1062, 1064, 1996Google Scholar

14. Daniels N, Sabin JE: The ethics of accountability in managed care reform. Health Affairs 17(5):50-64, 1998Google Scholar

15. Sabin JE: Lessons for U.S. managed care from the British National Health Service: I. "the vision thing." Psychiatric Services 46:993-994, 1995Link, Google Scholar

16. Daniels N, Sabin JE: Limits to health care: fair procedures, democratic deliberation, and the legitimacy problem for insurers. Philosophy and Public Affairs 26:303-350, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar