Impact of Robustness of Program Implementation on Outcomes of Clients in Dual Diagnosis Programs

Abstract

Three types of treatment—behavioral skills training, a 12-step recovery model, and intensive case management—provided to 132 clients at four facilities were identified as being robustly or not robustly implemented, depending on whether core elements of these treatments were emphasized. Outcomes and costs of services to clients were examined over 18 months. Clients receiving robustly implemented behavioral skills training had significantly higher psychosocial functioning and lower costs for supportive services than those receiving nonrobustly implemented training. Clients receiving robustly implemented case management also exhibited significantly higher psychosocial functioning and lower costs for intensive services than those in the nonrobust intervention. To be effective, dual diagnosis programs should better manage the robustness of implementation of planned interventions.

Only a few studies of programs for severely mentally ill people with substance-related problems have reported data about outcomes or implementation (1,2,3,4,5,6). Qualitative findings about three dual diagnosis interventions examined in a comparative study identified important ingredients in successful programming (6). They include adequate amounts of specialized training and consultation provided periodically over time and staff who have the time and motivation to serve clients who have frequent relapses and strong denial of their dual disorders over long treatment periods. Other factors in successful programming are reasonably small caseloads, clinical management and supervisory support dedicated to keeping staff morale and enthusiasm high, and carefully monitored and constrained intervention changes.

In the study reported here, our primary hypothesis was that differences in the robustness of implementation of an intervention contribute to differences in client outcome. To examine this question, we incorporated a variable emerging from the qualitative analysis of a cost-effectiveness study, the "implementation robustness" of an intervention, into several quantitative analyses of changes in outcomes for clients in the same study.

Methods

In a longitudinal study comparing the cost-effectiveness of three treatment approaches for severely mentally ill consumers with secondary substance use disorders, three approaches were used: behavioral skills training, case management, and a 12-step recovery model (6). Consumers were adults between the ages of 18 and 59, diagnosed by their treating psychiatrist as having co-occurring DSM-III-R axis I diagnoses of severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Most consumers had been recently discharged from 24-hour care or were identified by their outpatient therapist as needing treatment for dual disorders. Informed consent was obtained from eligible consumers at four community mental health centers, and they were interviewed and assigned to one of the three intervention models, using both randomized procedures (48 percent of the final sample) and nonrandomized procedures (52 percent of the final sample). Further details about sample selection are provided elsewhere (7).

A total of 132 consumers constituted the final sample for the study. A total of 101 consumers (77 percent) were men, and 92 (70 percent) were white. More than half the sample (78 consumers, or 59 percent) were between the ages of 18 and 33. One hundred consumers (76 percent) were diagnosed as having schizophrenia, and 61 (46 percent) had been hospitalized in the six months before entering the study.

Consumers were interviewed every three months over the 18-month study period. The study was conducted between January 1991 and April 1994. Thirty-one percent of the recruited consumers dropped out. Some differential dropout was noted between the three interventions (39 percent for the 12-step model, 28 percent for intensive case management, and 25 percent for behavior skills training), but these differences were not statistically significant.

Consumers were interviewed at baseline and at three six-month follow-up points using a modified version of the Social Adjustment Scale-II, known as the Social Adjustment Scale for the Seriously Mentally Ill (SAS-SMI), and the Role Functioning Scale to rate the level of psychosocial functioning of each subject (8). Interviewers also administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) by using the C-DIS-R computer program to score for number of symptoms of depression, mania, schizophrenia, and alcohol and drug abuse (7). The number of reported symptoms on each scale was summed to yield a total score for the statistical analyses.

Data on cost of care for both public and private mental health services were retrieved directly from the management information and billing system of the public mental health system in which the study was conducted (9). For these analyses, supportive services provided as part of the three interventions (outpatient visits, case management hours, medication visits, supported housing days, and day program days) were distinguished from intensive mental health services received (inpatient days, skilled nursing days, residential treatment days, and emergency visits), which were targeted for reduction through the interventions.

Information for the qualitative analysis of the interventions was based primarily on biannual semistructured interviews with all participating community mental health center staff and administrators, supported by a literature review of previous applications of the intervention approaches and a review of program documents (6). In addition, the consultants hired to provide guidance to staff implementing each of the three interventions were also interviewed by the qualitative researcher.

Within each intervention model were certain identifiable core elements that represented the essence of each intervention and that were most likely to influence outcomes. For each intervention, clients receiving all of these elements were coded in the data set as receiving a "robustly implemented" intervention.

Core elements in the 12-step recovery model were considered to be the degree to which staff actively engaged in teaching clients the 12-step recovery approach, in linking them to meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) in the community, and in recruiting and orienting AA and NA sponsors. Core elements in the behavioral skills model were considered to be the degree to which staff actively used the structured treatment model and its skill-building framework to promote relapse prevention and problem solving among clients. Core elements in the case management model were considered to be use of a team approach, psychoeducational groups about substance abuse, and psychiatric monitoring consonant with the case management plan addressing substance abuse issues.

We identified the program site, participating staff, and the time period during which all of the core elements of each intervention were robustly implemented during the three years of the study. For the statistical analyses, we then coded each client in the data set as being in the robustly implemented group or not (dichotomous code). The nonrobustly implemented interventions lacked the core elements of each intervention type.

Differences in psychosocial functioning, number of psychiatric and substance abuse symptoms, and costs of intensive and supportive mental health services were assessed using two-way analysis of variance to compare total means across the three treatment groups (including all time periods) and between the groups for clients receiving robust and nonrobust interventions in each model.

Results

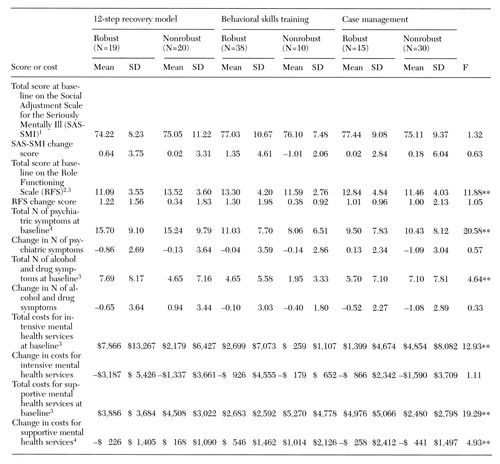

As shown in Table 1, clients receiving the robustly implemented interventions differed from those receiving the nonrobust interventions on several outcome dimensions, and significant interaction effects were noted across treatment groups. Total scores on the Role Functioning Scale indicated a significant interaction effect, with the psychosocial functioning of clients in the robustly implemented behavioral skills and case management interventions being significantly higher than that of clients receiving the robustly implemented 12-step intervention (F=11.88, df=2,474, p<.001). Mean scores on the Role Functioning Scale of clients in the nonrobust 12-step intervention were significantly higher than those of clients in the nonrobustly implemented behavioral skills and case management groups. No significant differences were found between clients receiving robust or nonrobust interventions in change scores over time on the two outcome dimensions of social adjustment and role functioning.

Psychiatric symptoms were significantly lower among clients who received the case management and behavioral skills interventions than among clients in the 12-step group, regardless of whether the groups were robustly implemented. No significant differences were found between clients receiving robust or nonrobust interventions in the change scores over time for these symptoms. For drug and alcohol symptoms, a significant interaction effect was detected, with the robust 12-step and behavioral skills group reporting a higher mean number of symptoms than their counterparts in the nonrobust groups, while clients in the robust case management group reported a lower mean number of symptoms than their counterparts in the nonrobust groups (F=12.93, df= 2,467, p<.001).

An interaction effect was also detected for costs of intensive mental health services, with significantly lower costs for clients receiving robustly implemented case management than for clients receiving the other two robustly implemented interventions and significantly higher costs for clients in the nonrobust case management group than for clients in the other two nonrobust groups (F= 12.93, df=2,487, p<.001).

A significant interaction effect was found for costs of supportive mental health services. Clients in the robustly implemented behavioral skills and 12-step groups had significantly lower costs for supportive services than clients in the nonrobust interventions, while clients in the robust case management group incurred higher supportive costs than those in the nonrobust case management group (F=19.29, df=2,487, p<.001) However, supportive costs increased significantly over time for clients in the robustly implemented behavioral skills model compared with the other models and groups.

Discussion and conclusions

Qualitative differences in program implementation appear to affect consumer functioning and service costs. In the case management model in our study, higher psychosocial functioning among clients, fewer symptoms of drug and alcohol problems, and lower costs for intensive services were significantly related to robust implementation—that is, the use of a team approach, psychoeducational groups about substance abuse, and psychiatric monitoring consonant with the case management plan focused on substance abuse issues.

In the behavioral skills model, the active use of the structured treatment model and its skill-building framework to promote relapse prevention and problem solving among clients was related to higher psychosocial functioning among clients, fewer psychiatric symptoms, and significantly lower costs for supportive services. When only the main group effects are considered, the behavioral skills intervention demonstrated better overall outcomes (4), but when the robustness of the implementation is taken into account, case management yielded better outcomes. However, the small size of the robust and nonrobust groups may effect the generalizability of these results.

We conclude that to be effective for consumers, dual diagnosis programs need to be aware of and manage the implementation robustness of their planned interventions, regardless of the specific intervention employed.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grant R01-MH46331 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Jerrell is professor of neuropsychiatry and behavioral science at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, 3555 Harden Street Extension, Columbia, South Carolina 29203 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Ridgely is senior policy analyst at the Rand Corporation in Santa Monica, California.

|

Table 1. Mean scores, change scores, and costs among 132 dually diagnosed clients receiving three types of robustly or nonrobustly implemented interventions over an 18-month period

1Possible scores on the SAS-SMI range from 24 to 114, with higher scores indicating better adjustment.

2Possible scores on the RFS range from 4 to 28, with higher scores indicating better functioning.

3Significant effect for interaction of treatment group and robustness

4Significant treatment group main effect (post hoc comparison)

**p≤.01

1. Bond G: Assertive community treatment of the severely mentally ill: recent research findings, in Strengthening the Scientific Base of Social Work Education for Services to the Long-Term Seriously Mentally Ill. Edited by Davis K, Harris R, Farmer J, et al. Richmond, Virginia Commonwealth University, 1989Google Scholar

2. Bond G, McDonel E, Miller L, et al: Assertive community treatment and reference groups: an evaluation of their effectiveness for young adults with serious mental illness and substance abuse problems. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 15(2):31-42, 1991Google Scholar

3. Drake R, McHugo G, Noordsy D: Treatment of alcoholism among schizophrenic outpatients: four-year outcomes. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:328-329, 1993Link, Google Scholar

4. Jerrell JM: Toward cost-effective care for persons with dual diagnoses. Journal of Mental Health Administration 23:329-337, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Morse G, Calsyn R, Allen G, et al: Experimental comparison of the effects of three treatment programs for homeless mentally ill people. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:1005-1010, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Ridgely MS, Jerrell JM: Qualitative analysis of three interventions for substance abuse treatment of severely mentally ill people. Community Mental Health Journal 32:561-572, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Jerrell JM, Ridgely MS: Comparative effectiveness of three approaches to serving people with severe mental illness and substance abuse disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183:586-596, 1995Google Scholar

8. Wieduwilt KM, Jerrell JM: Reliability and validity of the SAS-SMI. Journal of Psychiatric Research, in pressGoogle Scholar

9. Jerrell JM, Hu T: Estimating the cost impact of dual diagnosis treatment programs. Evaluation Review 20:160-180, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar