Characteristics of Persons With Mental Illness in a Representative Payee Program

Abstract

This study compared the characteristics of 56 clients with severe mental illness in a community mental health agency's representative payeeship program with those of 54 clients who did not participate in the program. Based on data from a two-year period, participants in the representative payee program were characterized by disability or financial distress, indicated by a diagnosis of schizophrenia, homelessness, lack of rent money, and lack of financial skills; long-term dependence on income from Social Security and services provided by the mental health system, evidenced by receipt of Supplemental Security Income and frequent hospitalizations; and lack of financial independence, as reflected by inability to earn income from employment and lack of financial support from family.

Representative payee programs have been developed to help persons with severe mental illness and substance abuse problems manage their finances. In these programs, responsibility for receiving a client's disability payments and disbursing funds for constructive purposes is assigned to a third party. These programs have been more successful when the representative payee is a responsible member of the client's family (1). Problems have been observed when payees have other relationships with clients. Unfortunately, clients with severe mental illness and substance abuse problems are likely to be living on their own and to lack responsible family members who will assist in managing financial affairs.

Recently, the Social Security Administration (SSA) and Congress attempted to increase the availability of qualified, noncustodial organizations to serve as payees (1). Payees' services may include paying for rent, utilities, medical expenses, and food. Case managers affiliated with these organizations may help clients fill out forms, obtain benefits, and learn to balance a checkbook, to adhere to a budget, and eventually to manage their finances independently.

A key issue in the success of representative payee programs is deciding which clients would benefit most from having a payee. Such decisions are important because agencies often lack sufficient resources to provide representative payees for all clients judged to need one. In addition, patients who are able to manage their own funds should not be denied their decision-making authority in this vital area. The final report of SSA's advisory committee recommended that SSA adopt a standard for determining who needs a representative payee that places greater emphasis on clients' functional capacity and less on their medical diagnosis (1). Examples of variables encompassed by functional capacity include stability in meeting housing and sustenance needs and regularity in paying bills.

We could find no reports of formal criteria for assigning clients a representative payee. Although Ries and Dyck (2) and Luchins and associates (3) have observed that dual diagnosis of severe mental illness and substance abuse is common among persons assigned a representative payee, very little is known about which clients are actually assigned payees, or why.

To begin developing criteria for identifying clients who need a representative payee, we conducted a study to identify the characteristics of clients with severe mental illness who were assigned to a representative payee program operated by a community mental health center. Their characteristics were compared with those of other clients who were eligible for but not assigned to the program.

Methods

In January 1996 we conducted a focus group with eight case managers at Community Counseling Centers of Chicago. The purpose of the group was to discuss criteria for assigning clients to a representative payee program. Using information from the group discussion, we developed a questionnaire to be used in a chart review to examine the differences between clients who were assigned a representative payee and those who were not. Although these clinical assignments could be incorrect, we believed that they would be generally valid because eligible clients were assigned to the representative payee program only after being a client at the community mental health center for at least a year. The assignments were based on decisions made by an interdisciplinary team, and the clients had stayed in the representative payee program for at least a year.

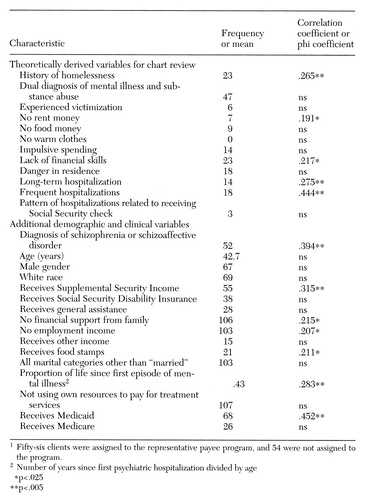

An expert panel reviewed the questionnaire, which resulted in 12 criteria for chart review, shown in Table 1. We also collected data on clients' demographic and clinical variables (also shown in Table 1), which provided additional, potentially useful characteristics.

To be eligible for the chart review, a client had to have a severe mental illness, such as a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or serious affective disorder that had persisted for at least two years. We reviewed the charts of 56 clients in the representative payee program. Data for these clients were collected for a period of one year before and one year after they entered the representative payee program. We selected 54 clients who did not have representative payees using a stratified random selection process. Data for these clients were collected for a matching two-year period.

The data were analyzed in two stages. First, we examined the bivariate correlations between each predictor and membership in the group with a representative payee or the group without a representative payee. This analysis revealed the variables that were significantly associated with membership in the representative payee group.

Second, we entered the variables that were significant in the correlation analysis into a logistic regression analysis using a stepwise forward conditional entry procedure. This procedure ranked the characteristics so that the most significant predictor would enter on the first step, the next most significant on the second step, and so on until no significant predictors remained (using a liberal entry criterion of p<.2).

Results

As Table 1 shows, 12 of the variables we examined were significantly correlated with group membership at p<.025. Of these, a subset of eight was selected in the regression analysis, which correctly identified the group membership of 83 of the 90 cases that had complete data available for the analysis. These eight variables, ranked from most to least significant, were: diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, receipt of Supplemental Security Income (SSI), years since first psychiatric hospitalization divided by client's age (proportion of client's life since first episode of mental illness), receipt of Medicaid benefits, history of a long-term hospitalization, history of frequent hospitalizations, no financial support from family, and no rent money.

This analysis has the limitation of capitalizing on chance variation in this particular sample. If another sample were used, the order of entry of the variables would probably change, and some of the four variables that were nonsignificant would probably become significant, while some that were significant in this data set would become nonsignificant. Therefore, we kept all 12 variables that were significantly correlated with group membership in drafting a screening measure called Determination of Need for Representative Payeeship (4).

Discussion

Five of the original 12 criteria had significant bivariate correlations with membership in the representative payee program. It is interesting to examine why the other seven original criteria—dual diagnosis of serious mental illness and substance abuse, history of victimization, no food money, no warm clothes, impulsive spending, danger in residence, and pattern of hospitalizations related to receiving SSA checks—were not significantly correlated with group membership. The easiest to explain are victimization, no food money, no warm clothes, impulsive spending, danger in residence, and pattern of hospitalizations. These variables may have been good predictors if their incidence had not been low; they simply may not have been reported by clients, may not have been easy to observe, or may not have been recorded by staff. If variables occur infrequently or are not readily reportable, observable, or recordable, they cannot easily be used as descriptors.

Some of the variables we used did not provide a valid measure of the phenomena that were actually of interest. For example, victimization reported by clients involved instances of violence such as robbery, rape, or battery. The incidence of these events was fairly low and probably not associated with the need for a representative payee. The more appropriate construct in considering assignment of a representative payee may be financial victimization, such as extortion, spending money on drugs, losing money gambling, being swindled, or being taken advantage of financially in various ways by acquaintances and family members.

It was surprising that dual diagnosis of serious mental illness and substance abuse did not correlate significantly with being assigned a representative payee. However, recent evidence generally appears to support this finding. In studies of homeless mentally ill clients entering the Center for Mental Health Services' Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports program, clients assigned a representative payee were not dramatically different from those who were not assigned a payee on measures of substance use and psychiatric symptoms (5).

Conclusions

Based on data from 56 participants in a representative payee program at a community mental health agency and 54 agency clients who had not been assigned representative payees, the best descriptors of program participants were indicators of financial distress or disability such as schizophrenia, homelessness, no rent money, and lack of financial skills; indicators of substantial long-term dependence on Social Security and the mental health system, such as receipt of SSI and long-term and frequent hospitalizations; and indicators of lack of financial independence such as failure to earn income from employment and lack of financial support from family. These factors begin to address the issues of beneficiaries' abilities and environment that have been called for in developing guidelines for assigning clients to a representative payee program. However, they are only a starting point. Validation studies on these and other promising variables with new samples of patients are needed.

Acknowledgments:

This study was supported by grants from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Illinois Department of Human Services, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and the University of Chicago. The authors thank Marc Shinderman, M.D., and Danielle Quasius.

Dr. Conrad and Dr. Matters are affiliated with the department of health policy and administration, School of Public Health (M/C 923), University of Illinois at Chicago, 2035 West Taylor Street, Chicago, Illinois 60612 (e-mail to Dr. Conrad,[email protected]). Dr. Conrad is also with the Veterans Affairs Hospital in Hines, Illinois. Dr. Hanrahan, Dr. Luchins, and Ms. Savage are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Chicago and with the Illinois Department of Human Services in Chicago. Ms. Daugherty is associate director of Community Counseling Centers of Chicago.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 110 clients of a community mental health agency and correlation of characteristics with assignment to a representative payee program1

1. Final Report of the Representative Payment Advisory Committee. Washington, DC, Social Security Administration, 1996Google Scholar

2. Ries RK, Dyck DG: Representative payee practices of community mental health centers in Washington State. Psychiatric Services 48:811-814, 1997Link, Google Scholar

3. Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P, Conrad KJ, et al: An agency-based representative payee program and improved community tenure of persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49:1218-1222, 1998Link, Google Scholar

4. Conrad KJ, Matters MD, Hanrahan P, et al: Determination of Need for Representative Payeeship (DONReP). Chicago, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1998Google Scholar

5. Rosenheck R: Disability payments and chemical dependence: conflicting values and uncertain effects. Psychiatric Services 48:789-791, 1997Link, Google Scholar