Managed Behavioral Health Services for Children Under Carve-Out Contracts

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Service costs and utilization patterns of children in carved-out behavioral health care plans were examined and compared with those of adults. METHODS: Twelve-month data on utilization and costs of behavioral health care from one managed behavioral health care carve-out organization, United Behavioral Health, were examined for three age groups of children—birth to five years, six to 12 years, and 13 to 17 years—and for adults. More than 600,000 enrollees in 108 different plans were included in the data. Rates of use and intensity of use were examined separately by type of service—inpatient, outpatient, and partial hospitalization. RESULTS: Only a small number of all enrollees used any behavioral health care services—4.2 percent used outpatient services, .3 percent used inpatient services, and .2 percent used partial hospitalization services. Adolescents were more than twice as likely as adults and about seven times as likely as children aged 6 to 12 to use inpatient services. Adolescents also had a slightly higher probability of using outpatient care than adults, while younger children had lower rates of outpatient use than adolescents or adults. Adolescents were also more likely than adults and other children to have very high costs of inpatient care (mean costs=$8,975 for adolescents and $4,750 for adults). Adults were more likely than other groups to have higher outpatient costs ($640 for adults and $513 for all children). CONCLUSIONS: The finding that children, and adolescents in particular, are more likely to have very high inpatient costs compared with adults implies that they may benefit most from the elimination of caps on mental health care costs covered by insurance. This profile of children's behavioral health care utilization patterns can be useful to policy makers in considering expansions in children's health insurance coverage.

One of the biggest changes in the behavioral health insurance market in the 1990s has been the growth of managed behavioral health care organizations that specialize in administering behavioral health care benefits that have been carved out of general medical care programs. Some of the success of carve-out firms has stemmed from their ability to intensively manage behavioral health care using modern techniques such as concurrent utilization review. In the past, managed care was often limited to primary care gatekeeping.

The new techniques of carve-out firms can dramatically alter health care patterns and costs. However, little is known about how these dramatic changes affect vulnerable populations, such as children. Reports of research on carve-out managed care are just emerging (1,2,3,4,5), and no research has focused specifically on children.

An understanding of behavioral health care utilization patterns among children is particularly important in light of recent legislation that gave states the authority and resources to expand programs to provide health insurance to uninsured children. This legislation could increase health care coverage among children, but the extent to which children's behavioral health services are included remains to be decided. In the past, concerns about costs have stymied many efforts by the mental health community. However, legislative debate has not always been informed by good data on cost and utilization patterns. For example, the assumptions used in the 1996 debate on the Mental Health Parity Act (6) overstated actual managed care costs by a factor of 4 to 8 (4).

This study examined children's cost and utilization patterns in carve-out plans and compared them with patterns of adults. We determined use of inpatient, outpatient, and partial hospitalization services and analyzed the distribution of children's inpatient and outpatient costs.

Methods

We investigated children's utilization of behavioral health care using data from one carve-out managed behavioral health care organization, United Behavioral Health, formerly U.S. Behavioral Health. The data, described in more detail elsewhere (7), reflected care access and utilization patterns of more than 600,000 enrollees in 108 different plans sponsored by employers, including both private-sector firms and public employers such as local and state governments.

Enrollees include 231,000 employees, 203,000 adult dependents of employees, and 172,000 child dependents of employees. The analysis used data for a 12-month period starting in 1995, which in some cases was the first year of a plan. Only enrollees with complete data for the entire year were included in the analysis. Enrollees who joined after the year's start or who left before the year's end were excluded to avoid censoring problems and selection effects (8). We considered use of managed network services only and explicitly excluded use of unmanaged nonnetwork services and out-of-plan services.

We examined the probability of any use of care and the intensity of service use separately, reflecting the standard multipart model for analyzing health care utilization (9). Use of care was defined as at least one use of a specialty behavioral health service during the 12-month period. Intensity of service use was defined as the amount of care received when services were used at least once during the year and was measured by the total cost of care.

The separate examination of any use of care and intensity of service use is appropriate given the patterns of utilization observed in behavioral health care. Only a small number of enrollees use any services; according to our data, 4.2 percent used outpatient services and .3 percent used inpatient services. In addition, a small percentage—10 percent—accounted for more than half of total costs of care.

We also classified utilization by general type of service—inpatient, outpatient, and partial hospitalization—given the differences in rates of use and costs across types of services. Inpatient services are far less frequently used and more costly than outpatient services, but despite their less frequent use, they accounted for half of total costs of care. Partial hospitalization, or intensive outpatient care, is a relatively new approach that is increasingly used by managed care firms to avoid more costly overnight stays, but we found that it is still used less frequently than inpatient services. Only .2 percent of enrollees used partial hospitalization services.

We compared adults to children, separating children into three groups: adolescents between the ages of 13 and 17 (N=55,000), children between the ages of six and 12 (N=62,000), and children from birth to age five (N=59,000). Previous studies of the demand for behavioral health services among children have reported differences in utilization patterns among children by age (10).

The patterns of children's utilization of behavioral health care that we report are specific to care under a carve-out organization and to the types of plans that govern individuals' utilization of care. The plans that employers offer under the carve-out are in general more generous than plans offered under a fee-for-service system. Typical mental health benefits offered in fee-for-service plans include a $250 individual deductible, a $500 family deductible, a 30-day cap and a 20 percent copayment requirement for inpatient hospitalization, a 20-visit cap and a 50 percent copayment requirement for outpatient services, and a lifetime cost cap of $50,000 (6). In comparison, most of the carve-out enrollees had no outpatient copayments (85 percent) and no deductibles (93 percent).

Most enrollees with an outpatient copayment had a 20 percent rate, less than half of the 50 percent rate for most enrollees in fee-for-service plans. Half of carve-out enrollees had no inpatient coinsurance costs, and the majority of those who did paid only 5 percent of costs. Only 30 percent of enrollees had a $50,000 or lower lifetime cap on care.

Results

Rates of use

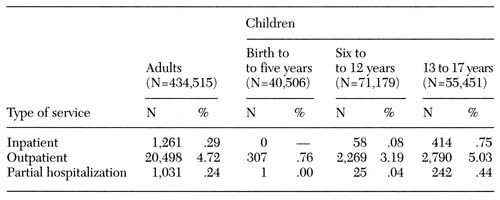

Table 1 reports rates of use of inpatient and outpatient care among adults and among children in the three age groups. The rate of use is the percentage of enrollees who used a service at least once during the one-year period. For example, .29 percent of adults used inpatient services at least once during the year.

Significant differences in use of inpatient services were found across age groups. Adolescents were more than twice as likely as adults to use inpatient services (χ2=301, df=1, p<.001 ) and about seven times as likely as children aged 6 to 12 (χ2=371, df=1, p<.001). Adolescents also had a slightly higher probability (6 percent) of using outpatient care than adults (χ2=10.7, df=1, p<.001), and younger children had lower rates of outpatient use than adolescents or adults (χ2= 276, df=1, p<.001).

Partial hospitalization rates were also higher for adolescents than for adults (χ2=37, df=1, p<.001). Among adolescents, .44 percent used partial hospitalization services, compared with .24 percent of adults. Very few children age 12 and under used partial hospitalization services.

We also investigated whether rates of use varied among adolescents by gender. Although outpatient use rates for male and female adolescents were similar, females were more likely to use inpatient services (χ2=6.4, df=1, p=.012). Among adolescents, .67 percent of boys used inpatient services, compared with .86 percent of girls.

Intensity of use

Children and adults differed in their intensity of service use and in rates of use. The hypothesis that the distribution of non-zero outpatient costs was the same for adults and for all children was rejected (z=12.4, p<.001), as was the hypothesis that the distribution of inpatient costs was the same for both groups (z=8.4, p<.001). When the comparison was limited to adolescents and adults, the same hypotheses were also rejected. Outpatient and inpatient costs differed significantly between adults and children.

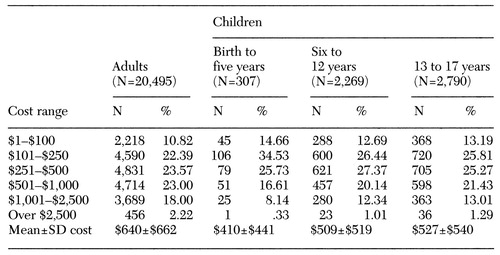

Table 2 reports the different ranges of costs for adults and children of different ages who used outpatient services. For example, 10.8 percent of adults who used outpatient services had total annual outpatient costs between $1 and $100, while 2.2 percent had costs over $2,500. The percentages in each of the columns sum to 100 percent, as data for each user is distributed in only one cost cell.

Children were more likely than adults to have outpatient costs between $1 and $500 (z>5, p<.001) and less likely than adults to have outpatient costs over $500 (3<z<9.5, p<.002). Among adult outpatient users, 43 percent had costs over $500, compared with 25 percent of very young children, 33 percent of children aged 6 to 12, and 36 percent of adolescents. The percentage of adults with outpatient costs over $2,500 was twice the percentage of adolescents (z=3.2, p<.001).

As Table 2 shows, adults who used outpatient services had an annual mean cost of $640. The mean±SD cost among all children was $513± $526. Very young children had somewhat lower costs than other children. The mean annual cost of outpatient services among children from birth to age five who used these services was $410, compared with $509 and $527 for children aged seven to 12 and 13 to 17, respectively.

The distributions of outpatient costs among adolescents significantly differed by gender (z=1.8, p=.08). Females had a greater probability of having costs of outpatient care over $2,500 (z=1.7, p=.09) and a 22 percent lower probability of costs less than $100 (z=2, p=.04).

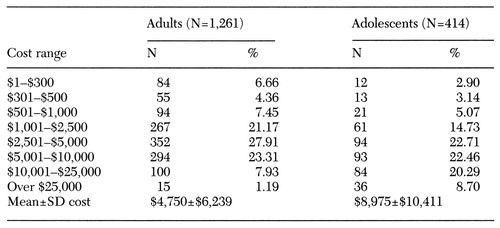

Table 3 shows the distributions of inpatient costs for adults and adolescents among users of inpatient services. Children younger than 13 were excluded because of the low rate of use in this group. The differences in inpatient costs for adults and adolescents are striking: adolescents were significantly less likely than adults to have inpatient costs lower than $5,000 and much more likely to have inpatient costs over $10,000. At almost every cost level below $5,000, children were underrepresented compared with adults (1.7<z<2.9, p<=.09). At the two cost levels above $10,000, children were overrepresented compared with adults (z=7, p<.001, for the next highest level and z=7.7, p<.001, for the highest cost level).

The percentage of adolescents with costs between $10,000 and $25,000 was two and a half times higher than the percentage of adults at this cost level. The percentage of adolescents with costs over $25,000 was seven times higher than the percentage of adults. Among adults who used inpatient services, the mean annual cost was $4,750, more than $4,000 less than the mean cost among adolescent users of inpatient services.

No statistically significant differences were found in partial hospitalization costs for children and adults. Overall, 33 percent of users of partial hospitalization services (30 percent of adolescents and 33 percent of adults) had costs less than $1,000, while less than 10 percent of users (8 percent of adults and 10 percent of adolescents) had costs over $5,000.

Discussion

This study found sharply different utilization patterns among children and between adults and children.

Differences among children

Among children, utilization differed most in the probability of use. Compared with older children, very young children rarely used services. Among children from birth to age five, we observed no inpatient use and a rate of outpatient use of less than 1 percent. Rates of use picked up considerably for children aged six to 12 and were greatest among adolescents—even greater than rates of use among adults. Compared with rates for children aged six to 12, adolescents' rate of inpatient service use was seven times higher and their rate of outpatient service use was 60 percent higher.

Without a measure of behavioral health status among all children, both users and nonusers of services, we cannot say whether the differences in rates of use reflect need or other factors. Previous studies on the prevalence of disorders suggest that some of the variation may be explained by differences in need. For example, John and associates (11) reported a strong negative correlation between being a younger child (age six to 11) and having a psychiatric disorder or social impairment. Offord and colleagues (12) found that 13.5 percent of girls between the ages of four and 12 had some type of psychiatric disorder, compared with 21.8 percent of girls between the ages of 12 and 16.

Other factors may also influence rates of use of behavioral health services. Children over age five may be more likely than younger children to receive care because problems are more likely to be identified once a child is in school. Adolescents may be more likely than children age 12 and under to receive care for a problem because of the nature of their disorders. Offord and coworkers (12) found that 12- to 16-year-old boys were more likely to have conduct disorders, while boys between the ages of four and 11 had more problems with hyperactivity. The more aggressive behavior of the older boys may be more likely to result in a referral, which may contribute to higher use of care by adolescents.

The difference in rates of use reflected in the data may misstate differences in rates of use per se, because the data do not include care received outside of the managed care network. In a study by Burns and associates (13), 70 percent of the nine-, 11-, and 13-year-olds who received care did so through the educational system. If more seven- to 12-year-olds receive care through their school than 13- to 17-year-olds, then the difference between the two groups in rates of use found in this study overstates the true difference. The lack of information on school-based care means that the difference in use rates between very young children and six- to 12-year-olds will be understated, because children under school age do not receive school-based care.

Differences across age groups in types of disorders may also influence rates of use, especially of inpatient care. Developmental delays account for a large share of behavioral health problems among very young children, and learning disabilities and attention-deficit disorders are common among children age six to 12. These types of problems are less likely to require inpatient care than those commonly found among adolescents, such as depression, substance abuse, and severe mental illnesses.

Differences between adults and children

Some dramatic and surprising differences were noted between adolescents and adults, especially given the two groups' frequent similarity of behavioral health problems. Compared with adults, adolescents were twice as likely to use inpatient care and were more likely to use outpatient care. Although prevalence of disorder may affect rates of use, we hypothesize that the high rate of inpatient use among adolescents may also result from other factors. For example, parents may prefer inpatient care for an adolescent with a behavioral health problem to limit the exposure of younger children in the home.

Adults were more likely to be high-cost outpatient users than adolescents, but adolescents were far more likely to be high-cost inpatient users. The higher outpatient costs observed among adults may result from their having more outpatient visits or using more expensive services. For example, we found that more adults than children saw a psychiatrist, whose fees are typically higher than those of other types of providers. Further investigation is required to determine to what extent the number of episodes of care, number of visits per episode, and costs per visit are responsible for this cost difference.

Further investigation is also needed to determine whether the higher inpatient costs for children reflect a greater number of inpatient episodes, longer stays per episode, or more expensive care. An initial investigation of inpatient provider types showed that adolescents were more likely than adults to receive inpatient services through a psychiatric hospital. Thus type of facility may explain some of the difference in inpatient costs.

Conclusions

Our profile of utilization patterns of managed behavioral health care documents some significant variations between adults and children. We found the greatest rates of use of both inpatient and outpatient care among adolescents. The rates were higher than those of younger children and adults. We also found that adolescents were more likely than adults to have very high inpatient costs. The percentage of adolescents who had inpatient costs over $10,000 was two and a half times greater than the percentage of adults with such costs. However, adults were more likely than adolescents to have higher outpatient costs.

One important implication of the findings concerns mental health parity legislation. Because of that legislation, many employers will remove limits or caps on the costs of mental health care covered by insurance. Since children, and adolescents in particular, are more likely to have very high inpatient costs compared with adults, they will benefit most from removal of the limits on care.

This profile of children's behavioral health care utilization under a carve-out contract is a start at providing policy makers with a better foundation of data on which to base decisions about expansions in children's health care coverage. Most proposals for increasing insurance for children have focused on extending coverage to uninsured adolescents in low-income families. The costs of providing Medicaid behavioral health coverage to adolescents can be predicted based on data from the comparison of utilization patterns of adolescents and other children and information on the costs of behavioral health coverage for young children currently insured through Medicaid.

Acknowledgments

Work on this paper was funded by grant MH-54147 from the National Institute on Mental Health to the Rand-University of California, Los Angeles, Research Center on Managed Care for Psychiatric Disorders and through NIMH grant MH-54623 to Dr. Sturm. The authors thank Bonnie Zima, M.D., and Bradley Stein, M.D., M.P.H., for helpful comments and William Goldman, M.D., and Joyce McCulloch, M.S., of United Behavioral Health for sharing their data.

Dr. Gresenz is an associate economist and Dr. Sturm is an economist at the Rand Corporation, 1700 Main Street, Santa Monica, California 90407-2138 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Liu is a doctoral candidate in the department of health services at the School of Public Health of the University of California, Los Angeles. This paper is one of several in this issue on mental health services research conducted by new investigators.

|

Table 1. Service utilization for a 12-month period among adults and children enrolled in a managed behavioral health care carve-out plan

|

Table 2. Outpatient costs for a 12-month period by enrollee type among adults and children enrolled in a managed behavioral health care carve-out plan

|

Table 3. Inpatient costs of adults and adolescents (13 to 17 years) among enrollees in a managed behavioral health care carve-out plan

1. Ma CA, McGuire TG: Costs and Incentives in a Mental Health Carve-Out. Boston, Boston University, 1997Google Scholar

2. Frank RG, McGuire TG: Savings from a Medicaid carve-out for mental health and substance abuse services in Massachusetts. Psychiatric Services 48:1147-1152, 1997Link, Google Scholar

3. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Sturm R: Costs and Utilization of Mental Health Services Before and After Managed Care. Paper 108. Santa Monica, Calif, Research Center on Managed Care for Psychiatric Disorders, 1997Google Scholar

4. Sturm R: How expensive are unlimited mental health benefits under managed care? JAMA 278:1533-1537, 1997Google Scholar

5. Sturm R: How Does Risk Sharing Between Employers and Managed Behavioral Health Organizations Affect Mental Health Care? Paper 113. Santa Monica, Calif, Research Center on Managed Care for Psychiatric Disorders, 1997Google Scholar

6. O'Grady MJ: Mental Health Parity: Issues and Options in Developing Benefits and Premiums. CRS Report for Congress, 96-466 EPW. Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, 1996Google Scholar

7. Sturm R, McCulloch J: Mental Health and Substance Abuse Benefits in Carve-Out Plans and the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996. Paper 105. Santa Monica, Calif, Research Center on Managed Care for Psychiatric Disorders, 1997Google Scholar

8. Gresenz C: Utilization and Cost of Managed Health Care: The Effects of Selection Into Plan and Employer. Paper 114. Santa Monica, Calif, Research Center on Managed Care for Psychiatric Disorders, 1997Google Scholar

9. Duan N, Manning WG, Morris CN, et al: A comparison of alternative models for the demand for medical care. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 1:115-126, 1983Google Scholar

10. Roughmann KJ, Babigian HM, Goldberg ID, et al: The increasing number of children using psychiatric services: analysis of a cumulative case register. Pediatrics 70:790-801, 1982Medline, Google Scholar

11. John LH, Offord DR, Boyle MH, et al: Factors predicting use of mental health and social services by children 6-16 years old: findings from the Ontario child health study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 65:76-86, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Offord DR, Boyle MH, Szatzmari NI, et al: Ontario child health study: six month prevalence of disorder and rates of service utilization. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:832-836, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Burns BJ, Costello EJ, Erkanli A, et al: Insurance coverage and mental health service use by adolescents with serious emotional disturbance. Journal of Child and Family Studies 6:89-110, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar