A Longitudinal Perspective on Entitlement Income Among Homeless Adults

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Sources of entitlement income were examined in a sample of homeless adults to determine whether certain subgroups more consistently obtain entitlement income and are more likely to continue receiving it over time. METHODS: From a baseline sample of 564 homeless residents of Alameda County, California, 397 were interviewed at both five- and 15-month follow-ups. Information was obtained on income received from public sources in the 30 days before each interview, including general assistance, Aid to Families With Dependent Children (AFDC), Supplemental Security Income, or Social Security Disability Insurance. Data were also obtained on psychiatric diagnosis, race, marital status, education, duration of homelessness in adulthood, household status, and reported disability. RESULTS: At baseline fewer than half of the respondents were receiving any entitlement income. The benefits of almost half of the AFDC and general assistance recipients were terminated during the 15-month period. Respondents who continued receiving entitlement income over the 15-month period were more likely to be black, to be women alone or with children, to have a family history of receiving welfare, and to report a disability. Respondents with dual disorders were six times more likely than others to have their benefits terminated. CONCLUSIONS: Entitlement income is tenuous for many homeless adults, particularly those with dual diagnoses.

Annual incomes of homeless adults are far below the national poverty level (1,2,3). One important income source for homeless adults is entitlement programs (1,3,4). However, some studies have suggested that homeless adults with mental disorders are less able to compete for income, including entitlements (3).

This study addressed two questions about homeless adults. Which subgroups obtain entitlement income, and which subgroups continue to receive it over time? We expected sources of entitlement income to differ by disability status and household composition.

Methods

A three-wave longitudinal sample of 397 respondents from the study of Alameda County homeless residents, called the STAR project, was obtained using a multistage cluster design over a 15-month period. The baseline sample was 564 respondents randomly sampled and interviewed in 1991. Interviewers had intensive training in data collection (5). Follow-up interviews were completed at five and 15 months with 397 of the 564 respondents (70.4 percent). Respondents received $20 for the baseline interview and $25 for follow-up interviews. More information on the STAR project methods is available elsewhere (5).

At baseline the Diagnostic Interview Schedule—Version III Revised (DIS-III-R), a standardized interview based on DSM-III-R diagnoses (6), was used to assess respondents for the presence of a major mental disorder or a substance use disorder. Information on age, race, marital status, education, duration of homelessness in adulthood, household status, receipt of welfare income by the respondent's family of origin, and self-reported disability was also collected at baseline.

Respondents reported any income that they received in the 30 days before the interview from public sources, including general assistance, Aid to Families With Dependent Children (AFDC), or Supplemental Security Income or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSI or SSDI). Median dollar incomes were based on data fromrespondents reporting at least $1 of income from an entitlement program.

SPSS and STATA programs were used for analyses. Weights were applied to equalize the probability of selection into the sample. Comparisons of the longitudinal and baseline samples indicated no significant differences in household status, age, education, race-ethnicity, marital status, duration of homelessness, reported disability, and diagnosis.

Because distributions of income were skewed, comparisons of incomes were made on proportions based on median splits of income at baseline using Cochran's Q tests. Data for 17 respondents whose income was more than two and a half standard deviations from the median were eliminated.

Logistic regression models were used to identify variables associated with termination of entitlement benefits. Only participants who received entitlement benefits were included in these models. Beta coefficients, odds ratios (ORs), and 95 percent confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the regression models.

Results

In this sample of 397 homeless adults, 72.1 percent were male. The median age was 35. Most respondents (72 percent) had completed high school. Many (66.5 percent) were black. About half had been married, and almost half had been homeless for a year or more. About 37.5 percent had a substance use disorder, and 20 percent had a major mental disorder or a concurrent major mental disorder and substance use disorder (dual diagnosis).

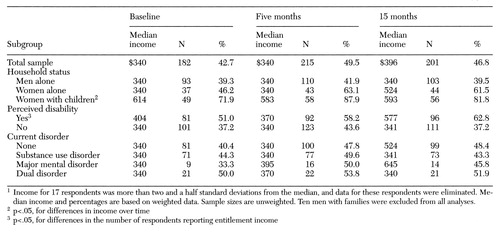

Table 1 presents data about entitlement income from all sources at baseline and at the five- and 15-month follow-ups. At baseline less than half of the sample reported entitlement income. Income varied significantly over time for women with children and for individuals who reported having a disability.

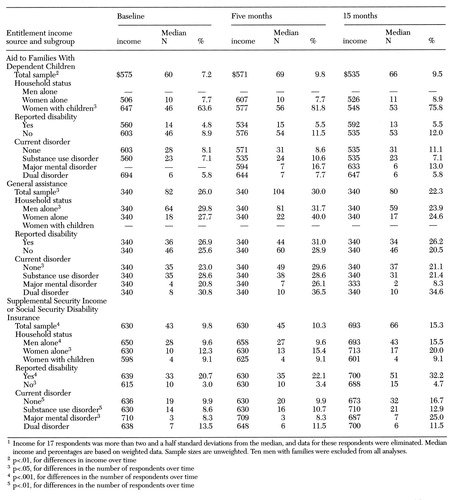

Table 2 presents data on entitlement income from specific sources at baseline and the two follow-up points. From baseline to 15 months AFDC income shrank from $575 to $535, a significant reduction. More women with children reported AFDC income at the follow-up interviews than at baseline. Although 78.5 percent of women who were alone at baseline had their children with them by the 15-month follow-up, few reported AFDC income (data not shown).

For general assistance, the total number of recipients and the number of male recipients both fluctuated significantly between baseline and the follow-up interviews. The $340 median monthly amount remained constant over time. However, among respondents with no disorder, the proportion reporting income from general assistance varied significantly over time.

Both SSI and SSDI entitlement programs target individuals with disabilities. As Table 2 shows, the number of adults who reported income from SSI or SSDI increased significantly over time. The significant increase was found for all subgroups except women with children and respondents with a dual diagnosis.

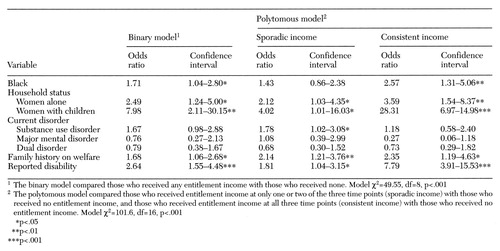

A logistic regression was conducted to predict receipt of entitlement income from any source. Variables entered into the regression models through backward stepwise elimination were household status, diagnostic status, black race, age over 35 years, homelessness for more than one year, family history of welfare, and reported disability. Table 3 shows the final binary and polytomous models.

The binary model indicated that respondents who reported any entitlement income were more likely to be black, to be women, to have a family history of welfare, and to report having a disability.

The polytomous model used a three-level dependent variable, including consistent income (entitlement income at all three time points), sporadic income (entitlement income at only one or two time points), and no entitlement income (the referent group). The polytomous model illustrated relationships more completely than the binary model. Respondents who were more likely to report entitlement income at all three time points were black, were women alone or with children, had a family history of welfare, and reported a disability.

Respondents with substance use disorders were more likely to obtain sporadic than consistent entitlement income. Women were more likely than men to report entitlement income, whether sporadic or consistent. Respondents who reported a disability were also more likely than those who did not to receive entitlement income, whether sporadic or consistent.

Among respondents with entitlement income at baseline, 91.3 percent of SSI or SSDI recipients continued to receive that income over the 15-month period, compared with only 53.2 percent of AFDC recipients and 39.8 percent of public assistance recipients.

In a logistic regression predicting termination of benefits during follow-up, respondents with a dual diagnosis were six times more likely than others to have their benefits terminated (OR=6.40, CI=2.16 to 19.02, p< .001). Blacks were more than twice as likely as nonblacks to have their benefits terminated (OR=2.35, CI=1.07 to 5.13, p<.05). Other factors—household status, reported disability, substance use disorder, and major mental disorder—were not associated with termination of benefits.

Discussion and conclusions

Less than half of the 397 homeless adults in this sample received entitlement income at baseline. Among those who reported such income, benefits were terminated for almost half of AFDC recipients and nearly two-thirds of the general assistance recipients within the 15-month study period. In contrast, 91 percent of respondents who reported income from SSI or SSDI at baseline continued to receive it over the course of the study.

Respondents with major mental disorders were no more likely to report entitlement income than other respondents. However, those with comorbid major mental and substance use disorders were six times more likely to have their benefits terminated during the study period. This finding provides evidence that some homeless adults with mental disorders may be less able than others to sustain entitlement income (7).

Respondents who reported consistent entitlement income were more likely to be black, to be women, to have a family history of welfare, and to report a disability. These four variables plus the presence of a substance use disorder were also associated with sporadic receipt of entitlement income—that is, income reported at only one or two of the three time points. Findings suggest that adults with substance use disorders were able to obtain entitlement income but not to continue receiving it.

Like other studies (1,4,8), this study found that at baseline entitlement income was more common among women than men, particularly women with children. Yet AFDC income is often insufficient to pay rent or other monthly bills (9). Many homeless women with children in this study who were ostensibly eligible for AFDC income were not receiving it, a finding consistent with other studies (8,,10). General assistance, an entitlement of last resort, was the most common entitlement benefit. However, only 39.8 percent of those who received such income at baseline reported receiving it 15 months later.

The study limitations include recall bias, income data based on 30-day periods before the interview, questions of generalizability of the results to other homeless samples, and the use of the DIS-III-R. Although the DIS-III-R is extensively used, it has not been validated with homeless populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cheryl Cherpitel, Dr.P.H., and Tammy Tam, Ph.D. This work was funded by grants MH-51651 and MH-46104 from the National Institute of Mental Health and grant DA-09334 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Dr. Zlotnick and Dr. Robertson are affiliated with the Alcohol Research Group of the Public Health Institute, 2000 Hearst Avenue, Suite 300, Berkeley, California 94709 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Lahiff is with the division of biostatistics of the School of Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley.

|

Table 1. Entitlement income from all sources at baseline and five- and 15-month follow-up among subgroups of 397 homeless adults1

|

Table 2. Entitlement income at baseline and five- and 15-month follow-up among subgroups of 397 homeless adults1

|

Table 3. Logistic regression models of variables associated with receipt of entitlement income among 397 homeless adults interviewed at three time points over 15 months

1. Breakey WR, Fischer PJ, Kramer M, et al: Health and mental health problems of homeless men and women in Baltimore. JAMA 262:1352-1356, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Fischer PJ, Shapiro S, Breakey WR, et al: Mental health and social characteristics of the homeless: a survey of mission users. American Journal of Public Health 76:519-524, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Koegel P, Burnam MA, Farr RK: Subsistence adaptation among homeless adults in the inner city of Los Angeles. Journal of Social Issues 46(4):83-107, 1990Google Scholar

4. Zlotnick C, Robertson MJ: Sources of income among homeless adults with major mental disorders or substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services 47:147-151, 1996Link, Google Scholar

5. Garrett K: Field Report for the Study of Alameda County Residents. Berkeley, University of California, Survey Research Center, 1994Google Scholar

6. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed, rev. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

7. Jahiel RI: Services for homeless people: an overview, in Homelessness: A Prevention-Oriented Approach. Edited by Jahiel RI. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992Google Scholar

8. Takahashi LM, Wolch JR: Differences in health and welfare between homeless and homed welfare applicants in Los Angeles County. Social Science in Medicine 38:1403-1413, 1994Google Scholar

9. Over the Edge: Homeless Families and the Welfare System. New York, National Coalition for the Homeless, 1988Google Scholar

10. Bassuk EL: Social and economic hardships of homeless and other poor women: homeless women: economic and social issues. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 63:340-347, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar