Customer Satisfaction and Self-Reported Treatment Outcomes Among Psychiatric Inpatients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Relationships among different dimensions of patient satisfaction and selected demographic, clinical, and outcome variables were explored in a sample of severely ill people receiving inpatient psychiatric services. METHOD: The sample consisted of 81 patients admitted to and discharged from an inpatient psychiatric unit at a midwestern Veterans Affairs medical center. Stepwise multiple regression was used to examine the relationship between patient satisfaction and self-reported changes in quality of life, symptomatology, and level of functioning as measured by the Treatment Outcome Profile. Other variables such as diagnosis, length of stay, employment, living situation, and prior psychiatric and substance abuse treatment were also considered. A subsample of the most satisfied and dissatisfied patients was chosen to further explore variables contributing to satisfaction with services. RESULTS: Patient satisfaction was related to initial level of functioning, certain diagnoses, and treatment gains. Clinicians were highly accurate in identifying patients who were satisfied, based on blind chart reviews. CONCLUSIONS: This study underscores the significant relationships between patient satisfaction, psychiatric diagnosis, and other outcome measures, and argues for the validity and utility of patient satisfaction measures in assessing the efficacy of inpatient care.

Measurement of customer satisfaction in behavioral health services has received increasing emphasis due to clinicians' and researchers' desire to measure outcomes that reflect the patient's unique perspective. Previous research has suggested that patients feel more positive about treatment outcomes than do staff and that patients and staff tend to disagree about what makes patients better (1). Administrators' desire to increase productivity and enhance quality of services is another reason for acceptance of the customer-service perspective.

Furthermore, policy makers are finding that outcome data measuring customer satisfaction can be useful in managing program development and resource allocation (2). Cost-effectiveness research is needed in health services, and a first stage of this research is measuring effectiveness from the patient's perspective (3). The growing recognition of the importance of patient satisfaction is also reflected in the requirements of regulatory and certification agencies, such as the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, which stipulate that treatment facilities collect and use patient satisfaction data in quality assurance activities (4).

However, controversy remains about the methods used to measure patient satisfaction and about the meaning and importance of patient satisfaction data in health services (5,6,7,8,9,10,11). It is generally recognized that customer satisfaction is multidimensional. For example, patients can be satisfied with the treatment staff but not with the environment in which treatment was provided (12,13). For these and other reasons, the relationship of customer satisfaction to other patient characteristics and to outcome data constitutes a compelling research domain (6,14,15).

In general, research has not found consistent relationships between patient satisfaction and patient demographic characteristics, except that minority patients tend to have lower satisfaction scores (15). Satisfaction also has been found to be lower among patients who abuse drugs and among suicidal patients, psychotic patients, patients with poor prognoses, and those who terminate treatment prematurely (5,10,14). Satisfaction with health services has been shown to be related to patients' pretreatment expectations of improvement (16). Patient satisfaction ratings also appear to be correlated with other outcome measures, especially if the measures are collected at the same time and similar measurement methods are used (9,17). Some researchers have argued that satisfaction with services is more closely related to distress or level of functioning at follow-up than to treatment gains (17).

The study reported here examined the relationship between three dimensions of patient satisfaction at discharge from inpatient mental health services and other key demographic, clinical, and outcome measures. Self-reported improvement in quality of life, symptomatology, and level of functioning are important outcome variables, and they were hypothesized to be predictive of patient satisfaction. The study addressed several specific research questions. First, we explored whether self-reported satisfaction with inpatient services was related to other important outcome variables. Second, we considered whether various dimensions of patient satisfaction were related to different outcome measures and to other demographic and clinical variables such as employment, psychiatric diagnosis, and clinicians' judgments about patient satisfaction and level of functioning. Third, we examined whether clinicians' ratings of patient satisfaction agreed with patients' self-reported ratings. Finally, we identified major demographic and clinical influences on satisfaction with services among psychiatric inpatients.

A major overall objective of this study was to evaluate the utility of self-reported patient satisfaction as an outcome variable for individuals with severe mental illness.

Methods

Measures

The Treatment Outcome Profile is a 27-item, self-report measure designed to assess changes in quality of life, symptomatology, and level of functioning among people receiving mental health services. Each of the three scales that measure these changes is based on previous factor-analytic research with inpatient and outpatient samples (8,18,19,20). Validity and internal reliability of the Treatment Outcome Profile has been established with inpatient clinical populations (21). (A copy of the profile is available from the first author.)

The fourth scale of the Treatment Outcome Profile measures patients' satisfaction with services. An underlying assumption of this scale is that patient satisfaction is multidimensional. The patient satisfaction scale consists of nine statements to which patients respond on a 5-point Likert-type scale. The nine items measure three dimensions of patient satisfaction. The first three items measure satisfaction with the effectiveness of treatment. The next three items measure the perceived competence of staff, and the last three items measure satisfaction with the treatment environment. Past research has shown that patients are able to discriminate between these different dimensions of satisfaction (8).

An example of a statement from the effectiveness dimension is "I feel better after receiving treatment." An example from the staff competence dimension is "Treatment staff were understanding of my needs." An example from the environment dimension is "My privacy was respected."

Besides the variables measured by the four major scales of the Treatment Outcome Profile, six other variables were chosen for inclusion in this study because of their hypothesized influence on patient satisfaction and treatment outcome. These variables were whether the patient lived alone at the time of admission, whether the patient was employed, diagnosis, length of stay, previous psychiatric treatment, and previous alcohol or drug abuse treatment.

Subjects

Previous research on patient satisfaction has focused primarily on outpatient services provided by community mental health centers (5). Subjects for this study were severely disabled patients admitted to a psychiatric unit in a Veterans Affairs medical center during the period from September 1995 to September 1996.

Patients who participated in the study completed the first three scales of the Treatment Outcome Profile at admission to inpatient treatment. At discharge, patients again completed the first three scales and in addition completed the nine-item patient satisfaction scale.

Eighty-seven consecutively admitted patients completed the Treatment Outcome Profile, and 81 completed follow-up measures at discharge, for a 93 percent completion rate. No significant differences on any of the independent measures were found between the 81 patients who completed the follow-up profile and the six who did not.

The average age of the 81 patients who completed both measures was 46 years. The average length of stay was 13.7 days. Thirty percent lived alone at the time of admission, and 33 percent had been in a combat role in the service. Fourteen percent were employed before admission. Thirty-seven percent were receiving a service-connected pension. Ninety-five percent were male, and 88 percent were Caucasian.

Thirty-four percent had a DSM-IV primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder or mood disorder, as determined by the attending psychiatrist. Twenty-six percent had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, 29 percent had posttraumatic stress disorder, 21 percent had an alcohol or drug use disorder, and 17 percent had a dual diagnosis of an alcohol or drug use disorder and another diagnosis. Twenty percent had a diagnosis of personality disorder, and 9 percent had an anxiety disorder. Ninety percent had received previous psychiatric care, and 27 percent had been admitted for inpatient care seven or more times. Forty-three percent had previous inpatient alcohol or drug abuse treatment. These characteristics underscore the severity and chronicity of the problems presented by the subjects.

Analysis

Stepwise multiple regression analysis, combining both backward and forward selection procedures (22), was used to explore the relationship of the three dimensions of patient satisfaction at discharge to admission and discharge scores on the scales of the Treatment Outcome Profile measuring quality of life, symptomatology, and level of functioning. Other key clinical and demographic variables were also included in the analysis. To explore the influences on patient satisfaction more completely, the most satisfied and most dissatisfied patients, according to their scores on the satisfaction scale of the Treatment Outcome Profile, were selected for further study (N=29). Patients were selected if they were one standard deviation above or below the mean score on the satisfaction scale (18 patients above and 11 patients below), which was completed at discharge.

The attending psychiatrist and the staff psychologist who had worked with the 29 patients were asked to review the medical records and to rate whether they believed each patient was satisfied or dissatisfied with treatment. Raters did not know whether the patients had rated themselves as satisfied or dissatisfied. Both raters assessed the records individually and then arrived at a consensus rating.

In addition, six other variables were investigated to determine if they would discriminate between satisfied and dissatisfied patients. The six variables were the number of discharge psychiatric medications and whether the patient was on an antipsychotic medication, was on an antidepressant or antianxiety medication, had a comorbid medical disorder, had received a medical consultation off the ward while in the hospital, and was assigned an individual therapist. These variables were included in a stepwise discriminant function analysis (22) along with diagnosis, clinicians' ratings of patients' level of functioning (axis V of DSM-IV ), admission scores on the Treatment Outcome Profile, and change in profile scores between admission and discharge.

Results

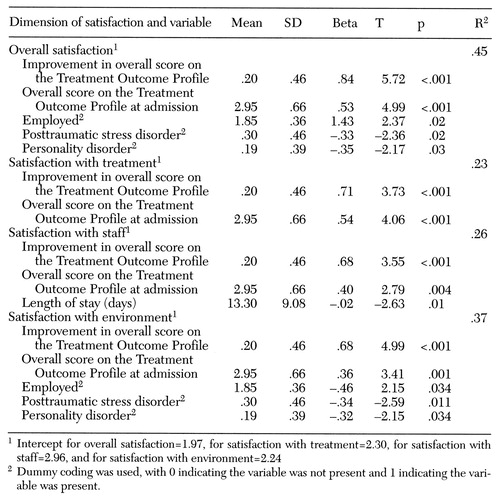

Table 1 shows the results of a stepwise multiple regression analysis using the overall satisfaction score on the Treatment Outcome Profile as the dependent variable. Five variables were included in the final model, which accounted for 45 percent of the variance in overall satisfaction scores. As both the admission Treatment Outcome Profile scores and the gains in scores from admission to discharge increased, the ratings of satisfaction with services also increased. Patients who were employed at the time of admission also tended to have higher satisfaction scores.

Diagnosis was included in the analysis using dummy coding for six diagnostic categories—schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or major depression, anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, personality disorder, and dual diagnosis of a substance use disorder plus one of the aforementioned diagnoses. The stepwise regression analysis included two of these categories in the ideal model. Patients who reported being dissatisfied tended to have a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder or a personality disorder.

Because satisfaction with services is a multidimensional construct, the three dimensions of patient satisfaction in the Treatment Outcome Profile were analyzed separately using stepwise regression analysis. Satisfaction with treatment was predicted by gain in overall score on the profile and by admission score on the profile. Satisfaction with staff was predicted by gain in overall score on the Treatment Outcome Profile, by score at admission on the profile, and by length of stay. Patients who had shorter lengths of stay tended to be more satisfied with the treatment staff.

Satisfaction with the treatment environment was best predicted by gain in overall score on the profile, overall score at admission on the profile, employment status at the time of admission, and absence of a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder or personality disorder.

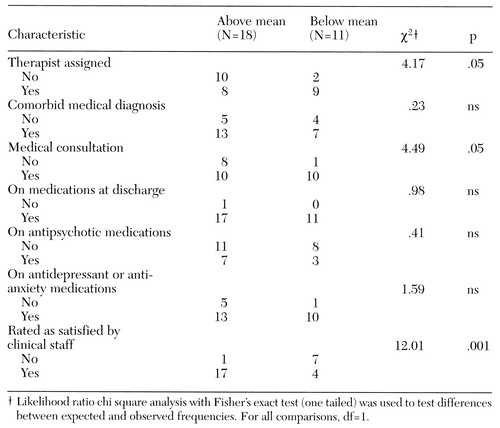

Results of chi square analyses using data from the blind review of the records of the 29 patients who scored one standard deviation above or below the mean on overall satisfaction are shown in Table 2. Surprisingly, the most satisfied patients tended not to have individual therapists assigned to them. Patients who were referred for medical consultations also tended to be relatively dissatisfied, compared with those who were not referred.

An interesting finding was the accuracy with which the clinician's blind ratings matched the patients' ratings of satisfaction. Both the attending psychiatrist and the staff psychologist were asked to arrive at a consensus on whether the patient was either satisfied or dissatisfied with services. The two clinicians accurately classified 24 of the 29 patients in the subsample (86 percent).

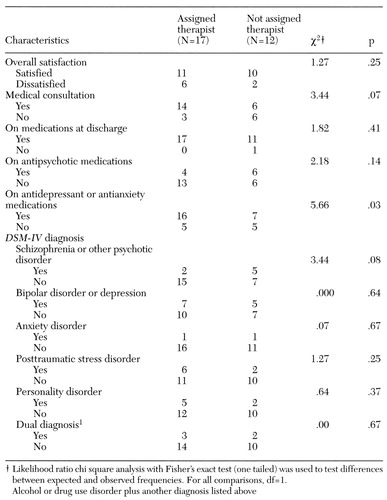

To explore more completely the counterintuitive finding that patients who were assigned individual therapists were more dissatisfied, those patients were compared with patients who had not been assigned individual therapists. As Table 3 shows, patients with assigned therapists tended to have a diagnosis of personality disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder. Patients with these diagnoses tended to be more globally dissatisfied with treatment. Therefore, the increased number of patients with these diagnoses assigned to therapists may have biased the subsample toward dissatisfaction.

Finally, discriminant analysis was used to analyze data from the subsample of patients who were most satisfied or most dissatisfied. The clinicians' ratings of satisfaction, along with diagnoses, clinical rating of level of functioning at admission (axis V), overall score at admission on the Treatment Outcome Profile, and change in score on the profile from admission to discharge were used as dependent variables. Satisfaction with services was used as the class variable. A 100 percent accurate classification of the 29 subjects was achieved. Three variables were included in the final classification model (χ2 =25, df=8, p<.001)—overall score at admission on the Treatment Outcome Profile (Wilks' lambda=.38, p<.001), change in overall score from admission to discharge (Wilks' lambda=.46, p<.001), and clinicians' ratings of satisfaction (Wilks' lambda= .60, p<.001). Using these three variables, a correct grouped classification rate of 93 percent was achieved, with misclassification of only two of 29 cases.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the capacity of the Treatment Outcome Profile to document satisfaction with psychiatric services and self-reported improvement associated with treatment among severely ill inpatients at a Veterans Affairs hospital. The utility of measuring patient satisfaction as a valid outcome measure of services was also supported by these results. Forty-five percent of the variance in overall patient satisfaction ratings with services was accounted for by gains in Treatment Outcome Profile scores and the demographic characteristics of the patients. Patients who reported fewer symptoms, higher quality of life, and a higher level of functioning at admission tended to be more satisfied with their services. In addition, patients who were employed at admission, and therefore most likely functioning at a higher level in the community, rated their treatment more positively.

An important finding of this study is that patients with diagnoses of posttraumatic stress disorder or personality disorder tended to be less satisfied with the services they received. Patients with personality disorder often have a long history of maladaptive responses to their environment, which includes their treatment. Similarly, patients with posttraumatic stress disorder may frequently feel disenfranchised and alienated from their surroundings, including the treatment environment. Thus their reports of higher levels of dissatisfaction are not surprising. No effects on level of satisfaction were associated with diagnoses of depression or anxiety, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorders.

The subgroups of the most satisfied and dissatisfied subjects could not be distinguished based on the type of medications they received, whether they were on medications at discharge, or how many medications they received. Clinicians' ratings of level of functioning (axis V) at the time of admission were also unrelated to satisfaction with services.

Initial positive ratings by patients of their quality of life, symptomatology, and level of functioning at admission were significantly related to satisfaction with treatment, staff, and the treatment environment. In addition, an excellent predictor of satisfaction with the treatment process was self-reported improvement. Patients' self-reported improvement as a result of treatment was significantly related to overall satisfaction with services, satisfaction with staff, and satisfaction with the treatment environment. These findings contrast with some previous work suggesting that patient satisfaction is related to level of distress at follow-up rather than to improvement as a result of treatment (17).

One of the interesting findings of this study was the high level of accuracy with which the treating clinicians were able to classify the most satisfied and dissatisfied patients (86 percent accuracy). The stepwise discriminant function analysis was able to construct a model that accurately classified 93 percent of the patients. Clinicians' ratings, Treatment Outcome Profile scores at admission, and gain in Treatment Outcome Profile scores were the three variables used in these classifications. In this study, treating clinicians were able to distinguish those who reported satisfaction with services from those who did not, which was not the case in previous research (1).

An unexpected finding was that patients who reported the most satisfaction tended not to have individual therapists assigned during their hospital stay. Eight of the 18 most satisfied patients, compared with nine of the 11 most dissatisfied patients, had assigned therapists. Perhaps the staff made judgments about which patients were most troubled (and least likely to report satisfaction with treatment) and assigned individual therapists to those patients. Also, subjects who were assigned therapists tended to have a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder or personality disorder, and both of these diagnostic groups were found to be more dissatisfied in general and more dissatisfied with the treatment environment. Thus the patients most likely to be dissatisfied tended to be the same ones who were assigned therapists.

The therapists on the unit were doctorate-level psychologists with many years of experience in applying behavioral and cognitive-behavioral techniques in treating people with posttraumatic stress disorder. This specialization could explain why more patients with posttraumatic stress disorder were assigned therapists.

Patients who tended to be dissatisfied were also more likely to be referred for a medical consultation, which suggests they may have had more physical problems. Ten of the 11 most dissatisfied patients had a medical consultation, compared with ten of the 18 most satisfied patients.

Conclusions

Self-reported patient satisfaction is a valid and important outcome measure that should be used in the evaluation of mental health services. This study demonstrated a significant relationship between patient satisfaction and other key patient variables such as self-reported initial levels of symptomatology and daily functioning and self-reported improvement from treatment, as well as specific diagnoses.

Submission for Datapoints Invited

Submissions the journal's Datapoints column are invited. Areas of interest include diagnosis and practice patterns, treatment sites, patient characteristics, and payment sources. National data are preferred. The text ranges from 350 to 500 words, depending on the size and number of figures used.

Inquiries or submissions should be directed to Harold Alan Pincus, M.D., or Terri L. Tanielian, M.A., Coeditors, Datapoints, Office of Research, American Psychiatric Association, 1400 K Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20005; telephone, 202-682-6294; fax, 202-789-1874; e-mail, [email protected],.

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by the Department of Veteran Affairs. The authors thank Summer Allen, Susan Breese, Robert Johnson, and Aaron Parker.

Dr. Holcomb, Dr. Thiele, and Dr. Higdon are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and neurology at the University of Missouri-Columbia. Dr. Thiele and Dr. Higdon are also with the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans Hospital in Columbia, Missouri, as is Dr. Parker. Dr. Parker is also affiliated with the department of internal medicine at the University of Missouri-Columbia. Dr. Leong is with the Veterans Affairs outpatient clinic and the department of psychiatry at Ohio State University in Columbus. Address correspondence to Dr. Holcomb at Behavioral Health Concepts, Victoria Park, 2716 Forum Boulevard, Suite 4, Columbia, Missouri 65203.

|

Table 1. Stepwise multiple regression analysis of variables predicting various dimensions of patient satisfaction among 81 severely disabled patients admitted to a psychiatric care unit in a Veterans Affairs medical center

|

Table 2. Characteristics of 29 patients who scored one standard deviation above or below the mean on the Treatment Outcome Profile measure of overall satisfaction with treatment at discharge

|

Table 3. Characteristics of patients who were and were not assigned individual therapists

1. Mayer JE, Rosenblatt A: Clash in perspective between mental patients and staff. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 44:432-441, 1994Google Scholar

2. McCarthy PR, Gelber S, Dugger E: Outcome measurement to outcome management: the critical step. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 21:59-68, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Phillips K, Rosenblatt A: Speaking in tongues: integrating economics and psychology into health and mental health services outcome research. Medical Care Review 49:191-231, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Accreditation Manual for Mental Health, Chemical Dependency, and Mental Retardation/Developmental Disabilities Services, Scoring Guidelines. Oakbrook Terrace, Ill, Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, 1995Google Scholar

5. Lebow JL: Client satisfaction with mental health treatment: methodological considerations in assessment. Evaluation Review 7:729-752, 1983Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Lebow JL: Consumer satisfaction with mental health treatment. Psychological Bulletin 91:244-259, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kalman TP: An overview of patient satisfaction with psychiatric treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34:48-54, 1983Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Holcomb WR, Adams NA, Ponder HM, et al: The development and construct validation of a consumer satisfaction questionnaire for psychiatric inpatients. Evaluation and Program Evaluation 12:189-194, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Pekarik G, Wolff CB: Relationship of satisfaction to symptom change, follow-up adjustment, and clinical significance. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 27:202-208, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Weinstein RM: Patient attitudes toward mental hospitalization: a review of quantitative research. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 20:237-258, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Ankuta GY, Abeles N: Client satisfaction, clinical significance, and meaningful change in psychotherapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 24:70-74, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Love RE, Caid CD, Davis A Jr: The user satisfaction survey: consumer evaluation of an inner city community mental health center. Evaluation and the Health Professions 1:42-54, 1979Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Tanner BA: Factors influencing client satisfaction with mental health services: a review of quantitative research. Evaluation and Program Planning 4:279-286, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, et al: Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning 2:197-207, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Tanner BA: A multidimensional client satisfaction questionnaire. Evaluation and Program Planning 5:161-167, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Hansson L, Berglund M: Factors influencing treatment outcome and patient satisfaction in a short-term psychiatric ward. European Archives of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences 236:269-275, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Lambert MJ, Hill CE: Assessing psychotherapy outcomes and processes, in Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 4th ed. Edited by Garfield SL, Bergin AE. New York, Wiley, 1994Google Scholar

18. Holcomb WR, Adams NA, Ponder FM: Factor structure of the Symptom Checklist-90 with acute psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 51:535-538, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Holcomb WR, Morgan P, Adams NA, et al: Development of a structured interview scale for measuring quality of life of the severely mentally ill. Journal of Clinical Psychology 49:830-840, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Holcomb WR, Mirilli E, Ahr PR: Reliability and concurrent validity of the Level of Care and Utilization Survey. Psychological Reports 75:779-786, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Holcomb WR, Parker JC, Leong GB: Measuring outcomes of inpatient psychiatric and substance abuse treatment. Psychiatric Services 48:699-704, 1997Link, Google Scholar

22. Norusis MJ: SPSS for Windows: Base System User's Guide, Release 6.0. Chicago, SPSS, 1993Google Scholar