County Funding of Mental Health Services in a Rural State

Abstract

Relationships between funding for mental illness in Iowa counties and county wealth, political activism, need for public services, rural culture, and policy makers' attitudes were examined. Counties with fewer people, lower proportions of persons with college education, higher proportions of rural and elderly residents, higher rates of poverty, and a higher proportion of income from farms spent less money on mental health services. Regression analysis indicated that the size of the county population and the proportion of persons receiving Medicaid funds explained 96 percent of the variation between county budgets.

A better understanding of factors that influence spending decisions for mental health services at the local or county level would be useful in service system development and in public policy planning. In a study of resource allocation by states, Braddock (1) found that factors accounting for variation in state funding for mental retardation±state size and wealth, federal aid, civil rights activity, and consumer advocacy±did not account for any appreciable variance in state funding for community mental health services. Reilly (2) found that local area boards possessed a large amount of control in developing policies, budgets, and program priorities for services to persons with mental illness. Furthermore, he observed that local political activism focusing on services for any particular group affected decisions made by the boards.

The hypothesis of this cross-sectional study was that county size, wealth, and political advocacy are associated with county funding for mental health services. The influence of rural culture on county funding was also considered.

Methods

Indicators of county spending for services to persons with mental illness (dependent variables) were defined as the number of dollars budgeted by the county for mental illness and expenditures for mental illness per county population for fiscal year 1994 (3). Independent variables selected from primary and secondary data sources were county wealth, which was operationalized as the total budget, the median income, and the average value of an acre of farmland; political activism, which was based on the number of people in the county who were members of the Alliance for the Mentally Ill (AMI), the presence of an AMI branch in the county, and voter turnout in the last election; the need for public services, which was based on the percentage of the population below the poverty level, a need index used by the Iowa Department of Public Health (4), the percentage of the population unemployed, and the percentage receiving Medicaid; whether the county had a rural culture; and policy makers' attitudes.

Rural culture was defined by several county-based socioeconomic variables including the size of the population, the percentage of land classified as rural, the percentage of elderly persons (age 65 and older), the percentage of people with a college education, and the percentage of total income from farm earnings. Policy makers' attitudes about services and funding priorities were assessed via a scheduled 15-minute phone survey of 97 of the state's 99 county boards of supervisors in the fall of 1995. The survey instrument was drafted by the first author (BMR) and found to have face validity by the Iowa State Association of Counties, the Alliance for the Mentally Ill, the Iowa Department of Human Services, and a representative of the Iowa Coalition, a consumer group (5).

Demographic data were obtained primarily from the census service (6) and the Iowa Department of Public Health (4). County population size was based on calculations made for the 1990 U.S. census. When possible, data from 1994 were used for all variables because county spending for mental health services was frozen in fiscal year 1994, and statewide Medicaid managed mental health care was implemented in March 1995.

Cross-sectional relationships between dependent and independent variables were examined using Pearson correlation coefficients. Predictors of funding for mental illness were identified by ordinary least-squares regression analysis.

Results

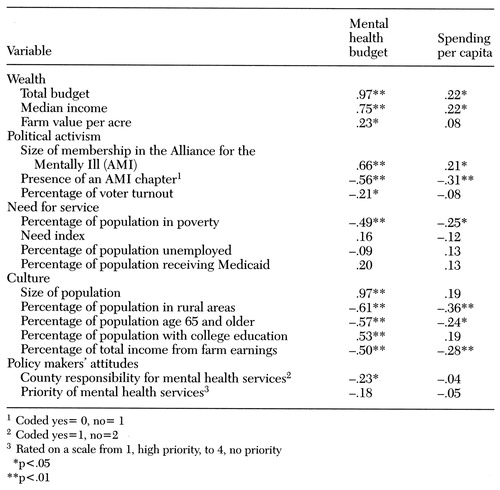

The results of analyses to determine factors associated with county funding for mental health services are summarized in Table 1. The amount of money spent on services to persons with mental illness was correlated with the amount of money spent on mental illness per capita (p<.05). County wealth, AMI advocacy, and characteristics related to rural culture, including population size, the proportion of rural and elderly inhabitants, the proportion of college-educated residents, and the proportion of farm income, all appeared to have a relationship with county funding for mental illness.

In the area of political activism, spending on services to persons with mental illness was correlated with the presence of an AMI chapter in the county and the level of AMI membership. However, higher voter turnout in a general election (in this case, the election of governor) was correlated with less spending for mental illness.

The only variable reflecting an objective need for service that was significantly related to funding for persons with mental illness was the proportion of the population below the poverty level in the county. Counties with higher proportions of the population below the poverty level had lower budgets for mental illness and spent less money per capita on mental illness. Counties with larger populations and higher proportions of college-educated residents spent more money on mental illness, while counties with higher proportions of rural and elderly persons spent less. Counties in which a higher proportion of income was from farm earnings spent less money on mental illness.

Finally, policy makers' attitudes were related to funding. County boards indicating that funding for mental health services should not be the responsibility of county government had lower budgets for persons with mental illness.

Because these univariate relationships did not control for the effects of other variables, a multivariate model was applied to clarify the interpretation of these findings. In ordinary least-squares regression analysis of the budget for persons with mental illness, the size of the county's population and the proportion of persons receiving Medicaid were significant (p<.05) and explained 96 percent of the variation in spending between counties (adjusted R2.958; regression coefficient=4,861,221.50, beta=.057 for percentage receiving Medicaid; regression coefficient=31.21, beta=.974 for size of the population).

Only 16 percent of the variation in the amount of money spent on mental illness per capita could be explained by the variables (adjusted R2.156). The variables with a significant relationship to per capita spending (p<.05) were the presence of an AMI chapter (regression coefficient=-7.45, beta=-.27), the percentage of the population unemployed (regression coefficient=3.08, beta=.28), and the proportion of poverty in the county (regression coefficient=-.50, beta=-.26).

Discussion and conclusions

Although cross-sectional studies such as this one cannot be used to establish causality, the correlations observed suggest relationships that warrant additional study. The size of the county population and the proportion of Medicaid recipients in the county explained most of the variation (96 percent) between county budgets for services to persons with mental illness. This finding suggests that Medicaid may provide increased availability of county-funded services and has important implications for the organization and delivery of mental health services in states such as Iowa that have Medicaid managed mental health care.

The results of this study suggest that aspects of rural culture apart from wealth and population size may influence county funding for mental illness. Although the reasons for these findings are not known, several possible explanations exist. Persons who live in rural areas may hold more conservative attitudes about the extent to which mental illness exists and is treatable. Priorities for county funding may be different in rural counties than in urban counties. Rural counties may spend less money on mental health services because less demand for services exists. While there is no evidence that rural populations in Iowa have less mental illness than their urban counterparts (7), stigma about mental illness and its treatment may be greater in rural areas, and, at the same time, anonymity in seeking services may be less assured. Although these and other explanations cannot be examined in the context of this study, they suggest important areas for future research in rural mental health.

Finally, advocacy by AMI was associated with higher county budgets for mental illness. Presumably, activism has an effect on funding because it influences the beliefs of board members. Analogous with Braddock's finding (1) about funding for mental retardation at the state level, our finding suggests that local advocacy may be an important factor in county funding for mental health services.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this study was provided by the Iowa Department of Human Services. The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Brenda Hollingsworth, M.A., in managing the database and conducting the telephone interviews and of Y. Kafui Etsey, M.Ed., in data management.

Dr. Rohland is assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Iowa College of Medicine, Psychiatry Research MEB, Room 1-400, Iowa City, Iowa 52242-1000 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Rohrer is professor in the division of health management and policy at the University of Iowa College of Medicine.

|

Table 1. Pearson correlation coefficients for variables associated with county budgets for mental health services and with per capita spending on such services in Iowa counties

1. Braddock D: Community mental health and mental retardation services in the United States: a comparative study of resource allocation. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:175-183, 1992Link, Google Scholar

2. Reilly DH: Reflections of a "battered" area board chairman (the contest of service versus politics). Community Mental Health Journal 30:105-117, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. County Expenditure Report. Des Moines, Iowa Department of Human Services, Division of Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities, 1994Google Scholar

4. Iowa Primary Care Access Plan. Des Moines, Iowa Department of Public Health, 1995Google Scholar

5. Rohland BM: A survey of county boards' views of funding for mental retardation versus funding for mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49:103-104, 1998Link, Google Scholar

6. Goudy W, Burke SC: Iowa's Counties: Selected Population Trends, Vital Statistics, and Socioeconomic Data. Ames, Iowa State University, Department of Sociology, Census Services, 1994Google Scholar

7. Conger RD: Health Status and Health Services in Rural and Urban Iowa: A Consumer Perspective. Testimony presented to the US Senate Appropriations Subcommittee for Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education. Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Feb 26, 1993Google Scholar