Focus on Women: Mentally Ill Mothers Who Have Killed: Three Cases Addressing the Issue of Future Parenting Capability

Abstract

Many parents with severe and chronic mental illness lose custody of their children due to child abuse or neglect. These children may linger in foster care for long periods of time until decisions about custody are made. Recent proposals to shorten the time that children remain in the foster care system include the use of categories of abuse to guide decisions about custody. One proposal has been to "fast-track" cases involving parents with long-standing mental disorders by automatically terminating parental rights. This approach assumes that a severe and chronic mental disorder is incompatible with safe parenting. This report describes three cases of mentally ill mothers who lost custody of their children after they killed someone. The mothers were nonetheless found to be at low risk for future child maltreatment and violence according to evaluation with two current methodologies, Parenting Risk Assessment and Risk of Violence Assessment. The cases question the assumption that mental illness is incompatible with safe parenting and underscore the fact that evaluation of the parenting competency of mentally ill parents is rarely clear-cut.

A large percentage of parents with severe and chronic mental disorders lose custody of their children at some point in their lives. Two independent studies of clinical samples estimated that about 60 percent of mothers with chronic mental illness do not raise their own children (1,2). When there is confirmed evidence of child abuse or neglect and a mentally ill parent has lost custody, decisions must be made about whether the parent is capable of resuming parenting responsibilities or whether parental rights should be terminated.

In the United States, a movement has arisen to "fast-track" these and other cases in the foster care system, that is, to decide within a short time span whether parental rights should be terminated or whether children in foster care should be returned to their parents (3). This movement is important because prolonged separations can have a long-term, negative impact on the well-being and functioning of children (4,5) and parents alike (6,7). Children who are in foster care are at heightened risk for psychopathology (8).

One approach to fast-tracking is to categorize different types of abuse to guide custody decisions (3). This approach recommends using three categories of maltreatment to determine the outcome of a given case. In this system, type I abuse, which encompasses cases of sexual abuse and torture, as well as cases where a parent has a long-standing and severe mental illness or mental retardation, would result in automatic termination of parental rights unless it is proven that this course of action is contrary to a child's best interests.

For type II abuse, which encompasses cases of serious physical abuse, long-standing neglect and abandonment, and long-standing alcohol and drug problems, the recommended course of action is to return the child home in 15 months or terminate parental rights after 15 months if the parents have not proven during that period that they are capable of caring for their children. For type III abuse, which includes cases of a parent who has engaged in minor abuse and less serious neglect or who has had less serious drug and alcohol abuse problems, the recommended course of action is to return the child home or to resolve the case through social work interventions outside of the court system.

This system posits that in some cases the risks to children are so obvious and so extreme that allowing parents time to improve their parenting skills would be futile and thus damaging to the children. A prime example of such a case would involve a mother with a major mental illness who had previously killed someone.

Substantial empirical evidence exists that major mental illness can compromise parenting abilities, although the effects of mental illness on parenting are not uniform (9,10,11). A mental disorder can also be a significant, albeit modest, risk factor for future violent behavior (12,13). At the same time, some mentally ill individuals are capable of raising their children safely (9,14). What is not clear is whether there is an empirical basis for assuming that any category of parents are permanently incapable of safe parenting, even in the most extreme instance of mentally ill mothers who have killed someone.

Literature on the parenting capabilities and the potential for violence of persons with severe mental illness who have committed homicide, infanticide, or neonaticide is scarce (14). One study of mothers without mental illness found that only a small percentage of mothers who kill are dangerous and at risk for future violence (15). On the other hand, some studies of men without mental illness who batter their wives have indicated a greater propensity for violence toward children as well (16). A major reason for the lack of systematic research on this topic is "sample censoring" (17): mentally ill parents who have killed and who regain custody of their children are few in number, because most persons with mental illness who have committed murder are considered to be at such high risk for future violence that they do not regain custody of their children.

Two different methodologies are currently available for addressing issues about future risk of violence. The first methodology, Parenting Risk Assessment, involves determining whether parents are at high risk for child abuse or neglect or whether they possess minimal parenting capability (18,19,20). The second methodology, Risk of Violence Assessment, is used to predict whether a mentally ill individual who has been violent in the past poses a substantial risk of harming others (21,22). Both approaches view the risk potential of mentally ill individuals as a multifaceted and complex phenomenon (22) and underscore the importance of assessing a comprehensive array of theory-based risk factors in multiple domains of functioning.

The approaches both emphasize the direct assessment of specific risk factors that are associated with child maltreatment and risk of violence, respectively; the direct assessment of situations that could evoke risk behaviors; and the determination of the likelihood of harm and its seriousness if these situations change. Risk is also treated in both methodologies as a probability estimate that can change over time and in different contexts (22). Moreover, risk factors can vary in their importance depending on how they interact with other risk factors and situations. Finally, both approaches emphasize a careful examination of the contribution of the mental illness and specific psychiatric symptoms, the course and prognosis of the illness, and the individual's responsiveness to interventions or treatment (13,19).

Although both types of assessment have a similar methodological philosophy, the Risk of Violence Assessment is specifically geared to assess the risk of future violence, including but not limited to violence directed toward children. The Parenting Risk Assessment specifically examines the risk of child abuse or neglect and also projects potential developmental pathways a child could take if he or she is returned to the parent (4).

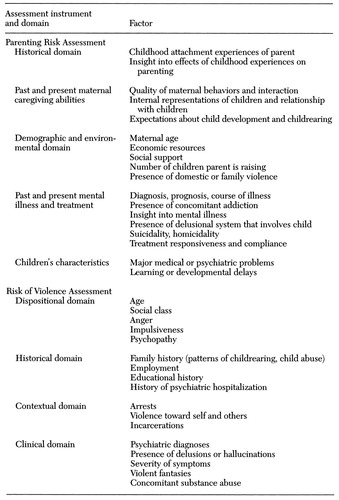

The Parenting Risk Assessment focuses on parents' caregiving capacity (23,24) and uses tools that directly assess various aspects of caregiving and factors known to influence caregiving. They include a parent's sensitivity and responsiveness to his or her children's cues and needs (25), internal representations and knowledge the parent has of his or her children as individuals (26,27), a parent's attitudes about childrearing and what can be expected of children of different ages (28), the stress a parent feels in the parenting role (29), whether a parent experienced trauma in childhood (30), a parent's insight into their mental illness (31) and its impact on parenting, and a patient's support network for parenting (32). Also assessed is whether children can use their parent as a secure base from which to explore their surroundings (4). (A more detailed description of specific assessment tools used to measure these domains and the empirical basis for their predictive value is presented by Jacobsen and colleagues [19] for the Parenting Risk Assessment and by Steadman and colleagues [22] for the Risk of Violence Assessment.) Table 1 summarizes the major domains and factors that are examined in the two types of assessment.

With respect to parenting assessment, responses to instruments that measure parent-child attachment are difficult to fake, because they rely on not only the parent's but also the child's behavior. The Parenting Risk Assessment and the Risk of Violence Assessment rely on several strategies that minimize bias and invalidation of the results due to inaccurate presentation or deception by patients for purposes of deliberate manipulation to regain child custody. These strategies include evaluation of individuals across different settings, use of a range of assessment tools, and use of different sources of information. The assessments include direct data collection from the patient and the patient's family, extensive interviews with collateral historians, and a review of psychiatric, psychological, medical, child welfare, and school records. Past and current records are reviewed to obtain a view of the patient's functioning over different periods of time.

When the Parenting Risk Assessment and the Risk of Violence Assessment are used in individual cases of mentally ill parents, a broad array of risk levels is found, consistent with the idea that mental illness has no uniform effects on parenting risk, including the risk of violence toward children. These findings suggest that it is not possible to reliably identify, based solely on diagnosis or history, a category of parents who will never be capable of adequate parenting.

To illustrate this point, this paper presents three cases of mothers with mental illness, each of whom committed one of three categories of killing pertinent to child welfare cases: neonaticide, or killing of a newborn; infanticide, or killing of a young child; and killing of an adult. A Parenting Risk Assessment and a Risk of Violence Assessment conducted in each of these cases suggested a low level of risk for future maltreatment of children. The names and identifying details in these cases have been changed to protect patient confidentiality.

The sources of data used to assess risk in each of these cases included unstructured and semistructured patient interviews; psychiatric record review; interviews of multiple collateral historians; home visits; videotapes of a standardized observation of parent-child attachment (25,33); responses to the Parent Opinion Questionnaire (28), the Parenting Stress Inventory (29), the Parenting Support Inventory (32), a childhood experiences questionnaire (30), and the Home Inventory (34); an assessment of the parent's internal representations of her children (26); responses to the Insight Into Mental Illness Scale (31); and a criminal background check based on the Law Enforcement Agencies Data Systems.

Case presentations

Case 1: neonaticide

Ms. A, a 16-year-old mother with chronic dysthymia and posttraumatic stress disorder, came to the attention of the state child protective agency after she killed her newborn infant. Unaware that she was pregnant, Ms. A delivered her infant in a toilet. She subsequently placed the infant in a plastic bag in the basement and notified a relative. She was charged with manslaughter and spent several months in a juvenile detention home. During that time, Ms. A's mother raised Ms. A's first child, then age one.

Ms. A subsequently developed additional psychiatric problems. She suffered from vivid flashbacks of the baby's birth. She developed insomnia, crying spells, and intermittent depressed mood. She withdrew from friends. She became pregnant with a third child. This time she was fully aware of the pregnancy but concealed it from others. Because she deliberately concealed the pregnancy, she lost custody of this baby at birth.

A Parenting Risk Assessment was requested three years after the neonaticide to determine whether Ms. A should regain custody of her children, who were then one and four years old. The Parenting Risk Assessment revealed that Ms. A had maintained regular contact with her children since her loss of custody. In both a home and a clinical setting, she showed positive parenting skills and responded readily and sensitively to her children's cues (25). Her children directly sought her out for comfort when needed and were able to freely explore their surroundings in her presence (4,33). Ms. A had positive internal representations of her children and clearly valued her relationship with them (26). She could separate her own needs from those of her children. She had appropriate expectations about what could be expected of children of different ages (28).

A psychiatric interview and record review found that Ms. A had no current psychiatric symptoms. She had no history of violence or suicide attempts. After the neonaticide, Ms. A had occasional thoughts of wishing she were dead but did not act on these thoughts. Since the neonaticide, she had become involved in individual psychotherapy. She had developed a trusting relationship with her therapist and was directly discussing the neonaticide, her role in the death of her infant, and family problems.

Ms. A's complete suppression of her second pregnancy and her concealment of her third pregnancy were conditioned by substantial psychological and family problems already evidenced at the time of her first pregnancy at age 13. Her parents made it clear at that time that abortion was never an option. Her father blamed her mother for allowing the pregnancy to happen. He began drinking and often beat her mother after this incident. Family members repeatedly admonished Ms. A for the pregnancy and asked her how she could have done this to her mother.

Denial of pregnancy followed by neonaticide is a well-known phenomenon (35). In these cases, the mother is typically an unmarried, immature teenager who experiences the pregnancy as an overwhelming stress. This phenomenon usually occurs in a family context where the girl fears that revealing a pregnancy to her parents would have dire consequences.

Sometimes the girl is aware she is pregnant and deliberately conceals the pregnancy from others. The more dangerous situation involves the girl who under intense psychological pressure suppresses awareness of the pregnancy even from herself. She reinterprets or ignores physical changes. In these cases, the baby is typically delivered without preparation, often in a toilet. The sudden appearance of the baby triggers overwhelming panic in the mother, who either actively kills the baby or leaves the baby in the toilet to drown. After that, the mother may develop posttraumatic stress disorder, characterized by flashbacks, insomnia, and social withdrawal.

Ms. A's case belonged to the more dangerous scenarios for neonaticide because she fully denied her pregnancy and had reinterpreted major physical symptoms of the pregnancy. For example, she believed that the baby's kicking was due to gas and interpreted labor pains as signaling a need for a bowel movement.

The psychological and family problems that led Ms. A to conceal two pregnancies and kill her second baby were substantial. An evaluation of Ms. A's social support network, undertaken as part of the larger Parenting Risk Assessment, revealed that since the neonaticide, Ms. A had been living separately from her parents and had become less emotionally and financially dependent on them. She had established a small, but viable, support network for parenting. The assessment produced no evidence that her children were at risk of abuse from her. It also seemed highly likely that Ms. A's growing maturity and independence would lead her to approach a future pregnancy in a different manner.

The Risk of Violence Assessment revealed that Ms. A had no history of violent behavior. Several measures, including self-report, criminal record review, school reports, and interviews with collateral historians, supported this assessment. The one exception was the instance when she placed her newborn infant in a plastic bag and left it in the basement. This behavior had occurred in the context of a complete denial of pregnancy and considerable family pressure. Although Ms. A denied her next pregnancy, it seemed highly unlikely that she would deny any subsequent pregnancy or that she would kill a newborn. She had matured considerably since the neonaticide, had become independent of her family of origin, and was no longer influenced by pressures regarding pregnancy.

Ms. A's behavior with the newborn did not appear to be linked to dysthymia. When she was depressed, she had thought of suicide occasionally, but she had no history of suicide attempts. Her posttraumatic stress disorder appeared to be largely conditioned by the neonaticide. Nonetheless, when she was in individual therapy, Ms. A began to recall memories of early sexual abuse and talked openly about violence she witnessed between her stepfather and mother as a child. Although these factors could contribute to her experiencing anger and responding with violence, this explanation also seemed unlikely as she had been openly addressing these issues in therapy and was seeking out relationships and friends who had more healthy patterns of interaction. Finally, Ms. A had no history of other risk factors, such as alcohol or drug use.

Based on these recommendations, Ms. A regained custody of her children. She had provided safe parenting for about one year at the time this report was prepared.

Case 2: infanticide

Ms. B, a 17-year-old single mother with recurrent major depression, was convicted of involuntary manslaughter of her second child, Mary. Ms. B's repeated hitting of her daughter over a period of several months had contributed substantially to her death at age one. The autopsy revealed multiple bruises on the small body and head.

Ms. B lost custody of her first child at the time of her conviction. During her jail term, she delivered a third child. Subsequently, after her release from jail, she regained custody of her children. She again lost custody of her children ten years later, when she told her therapist that she was feeling the way she did when she killed Mary. At that time she was experiencing an episode of major depression. Two years later a Parenting Risk Assessment was requested to determine whether Ms. B could safely raise her children or whether parental rights should be terminated.

The Parenting Risk Assessment revealed that many parenting stresses were present when Ms. B killed Mary. At that time, she had been a teenage mother caring for two small children under age five (John, age three, and Mary, age one). When John was born, Ms. B had lived with her mother, who had helped care for John. At the time of Mary's birth, Ms. B had moved in with the father of her children. He was addicted to drugs and alcohol and was beating Ms. B regularly and severely. He would not allow her to leave their apartment or to socialize with anyone.

Ms. B no longer had support from her family of origin because they disapproved of her partner. Mary began to have feeding problems and often cried inconsolably. Ms. B became depressed and began hitting Mary in the head when she would not stop crying, or after she herself was hit by the children's father.

Ms. B's second custody loss and depressive episode also occurred in the context of overwhelming stress: pregnancy complications, birth of a new child, abandonment by her partner, poverty, and use of medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera), a birth-control hormone that can cause depression as a side effect. At this time, Ms. B had four children who were younger than age 12.

Several current protective factors emerged in the Parenting Risk Assessment. On various cognitive, affective, and behavioral measures, Ms. B was found to have adequate caregiving abilities. She had appropriate ideas about what could be realistically expected of children of different ages (28). She had a balanced and realistic internal representation of her children and her relationship to them (26), and her interactions with her children were positive. She was able to read their cues and was sensitive to their needs. She showed no signs of hostile or intrusive behaviors, which are more prevalent in parents who physically abuse a child (25).

As for her mental illness, Ms. B could readily recognize the circumstances that triggered her depressive episodes and had previously sought and accepted help when she needed it. Although she herself had experienced an abusive and insecure childhood, she showed good insight into the effects of childhood experiences on her current parenting. She also acknowledged responsibility and remorse for Mary's killing and stated that this experience had forced her to mature and to try to be a better parent. Ownership of problems is a critical prerequisite for changes to occur in parenting (36).

Some risk factors were also present. Ms. B had four children to care for. Two had major developmental delays, and two were under age five. Her partner had frequently abandoned her in the past. Her continued reliance on his inconsistent support for parenting prevented her from identifying and maintaining other supports. Ms. B's depression was also a major risk factor. Record review revealed that when Ms. B had a major depressive episode, her parenting became impaired. She was less responsive to her children's cues, less able to meet their needs, and less apt to stimulate them. However, when Ms. B was not depressed, observations showed that her children enjoyed her presence and could use her as a secure base from which to explore their surroundings (4).

Several key issues needed to be considered in determining Ms. B's level of risk for future child maltreatment. They included the likelihood of relapse into depression, the likelihood that Ms. B would seek and accept help if she became depressed again, and the likelihood that Ms. B would abuse or grossly neglect her children if she became depressed.

Although there were no certain answers to these questions, there were probable answers. Ms. B's past depressions had all occurred under conditions of overwhelming stress. Her depression remitted when the stresses were no longer so acute. If overwhelming stress recurred in Ms. B's life and if she had inadequate support, her depression would probably recur.

As for her likelihood of seeking help when she became overwhelmed, the prognosis was good. When she was a teenager and killed her baby, she was socially isolated and was being abused herself. Since then, she had generally sought, accepted, and received help when she became depressed. Her recent custody loss was triggered by her acknowledging that she felt depressed and overwhelmed and needed help. Therapists working with her had uniformly found her to be responsive to therapy.

The likelihood of future abuse or neglect was also closely linked to Ms. B's relationship with her partner. At times he was supportive, showing a long-standing pattern of sporadic efforts to improve, followed by reneging on family responsibility. Unless this relationship could change, the risk of future maltreatment of the children was viewed as high. When Ms. B received feedback about the evaluation, she completely broke off her relationship with her partner and began to build a solid support network with family members and neighbors. Although Ms. B had killed an infant, the findings from the evaluation indicated that if she could build and maintain a solid support network for parenting, she would be at low risk for future maltreatment.

The Risk of Violence Assessment revealed that except for her repeated hitting of Mary, Ms. B had no history of violence toward anyone else. She denied ever having suicidal thoughts or attempting suicide, and there was little evidence that she was an angry, impulsive person. Ms. B also had no history of drug or alcohol abuse. These findings were corroborated by criminal background checks, by her therapist, and by interviews with collateral historians. Her beating of Mary was not an isolated instance of violence, however, and had occurred repeatedly over the course of several months.

Although this history should not be minimized, it is significant that it occurred in the context of depression, extreme stress, and social isolation, when Ms. B was young and was herself being beaten. Substantial evidence existed that she had matured considerably since that time. She had left her abusive partner. She had become engaged in and had responded well to therapy. In therapy, she had also explored her own sexual abuse by a relative in childhood and her witnessing of domestic violence between her mother and stepfather. When her depression recurred ten years after the first episode, she immediately told her counselor, as she was concerned that she could potentially place her children in danger again.

Ms. B had also developed a solid, though small, support network for parenting. Moreover, after Mary's death, Ms. B had been able to safely care for her four children for ten years. If Ms. B could maintain her support network, she appeared to be at low risk for future depression and violence. Ms. B is still in the process of regaining custody of her children.

Case 3: killing of an adult

Ms. C, a 22-year-old woman, killed a friend by beating her repeatedly in the face. The killing occurred during a psychotic break. Ms. C called the police after the event and stated that although she could not recall killing her friend, she must have done so because she had found her friend dead, the door was locked, and no one else was present. She was found not guilty of homicide by reason of insanity and was admitted to a psychiatric unit, where she remained for three years. During that time, she delivered a daughter and voluntarily relinquished her care to a relative. She was discharged on haloperidol, asymptomatic, with a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder.

Ms. C took her medication regularly and remained asymptomatic until she became pregnant again. At that time her medication was discontinued due to the pregnancy. In her seventh month of pregnancy, she had hallucinations and paranoia. She decided to "wait it out" until she delivered, because then she would be able to resume her medication. During this time, she missed a probation appointment and was psychotic when the judge saw her in court. She was subsequently admitted involuntarily to a psychiatric unit. She voluntarily relinquished custody of her second child to a close relative.

After delivery she resumed taking haloperidol, this time in the form of long-acting decanoate injections. Her psychotic symptoms remitted within a few weeks. She remained asymptomatic until her next pregnancy, when her physician discontinued her haloperidol. Psychosis again recurred in the seventh month of pregnancy.

This time Ms. C asked her doctor for haloperidol. He prescribed a small dose but not her regular amount. Although this regimen kept her out of the hospital during pregnancy, she became psychotic the day she delivered her third child. At that time she was paranoid and made threats to "kill myself, kill my child, kill everyone." The state child protective agency took custody of her newborn. She was subsequently placed back on her usual dose of haloperidol; she quickly became asymptomatic and remained so.

A Parenting Risk Assessment was requested two years later to determine the anticipated level of risk if Ms. C's youngest child, then a two-year-old boy, was returned to her care. An examination of her parenting abilities and of factors that are known to directly influence parenting revealed a mixed picture. Ms. C had good cognitive understanding of different childrearing practices and disciplinary techniques (28), and she had a large social support network (32). The viability of this network was confirmed through interviews with collateral historians.

At the same time, several risk factors were present. Ms. C had a tendency to minimize the stresses of parenting (29). In interacting with her son, she tended to strongly direct and correct his behavior, rather than allowing him to initiate activities on his own (25). She also had somewhat negative perceptions of what her son was like and described him as "noncompliant and difficult." In observations with his mother both in the clinic and at home, Ms. C's son seemed apathetic and passive in her presence. His performance on a standard developmental test (37) showed that he had several delays in cognitive and linguistic development.

A mental status examination, undertaken as part of the larger Parenting Risk Assessment, revealed that Ms. C had coherent thought processes, with no loose associations, hallucinations, delusions, or suicidal or homicidal ideation. Her past symptoms were consistent with the diagnosis of schizophrenia (38). Ms. C had been highly responsive to pharmacotherapy with antipsychotic medication and was asymptomatic whenever she had taken medication regularly. She had demonstrated an excellent ability to manage her own self-care and function on a high level. Whenever she was without medication, however, her psychosis had recurred, sometimes with highly dangerous behaviors.

Thus while she was psychotic, Ms. C would be at high risk of neglecting and abusing a child due to behaviors that could be highly influenced by delusional beliefs, as had happened in her past episodes. When she was not psychotic, she did not exhibit violent behavior.

Some parents with schizophrenia have difficulty reading and responding to subtle nonverbal cues, which are essential for parenting (39). The Parenting Risk Assessment suggested that Ms. C had difficulties in this area, but because she had never had the opportunity to parent her children, it was not fully clear whether her difficulties were due to residual symptoms of schizophrenia, lack of experience, or both. There were some indications that she would benefit from interventions designed to improve her parenting. She was highly motivated and was taking medication regularly. She was also regularly attending group therapy.

Parenting rehabilitation efforts, such as coaching in the context of a therapeutic nursery, have successfully improved the parenting capability of many patients with schizophrenia (40). Thus a trial of intensive parenting rehabilitation could demonstrate whether Ms. C could respond to such intervention. If she could respond, the risk to her parenting would be considerably less.

After the Parenting Risk Assessment, Ms. C became involved in an intensive parenting rehabilitation program that included daily participation with her son for several hours at a time. A follow-up evaluation six months later showed marked progress. Her interactions with her son were more positive, as were her internal representations of him and of their relationship. Ms. C's son's developmental quotient had also improved.

A central remaining question concerned the likelihood of a relapse of her illness, given that she could become violent if she became psychotic again. However, once a person is responsive to a medication, the response generally persists over time. The major issue, then, was the likelihood that Ms. C would continue to take her medication. Ever since beginning a regimen of decanoate injections, she had adhered successfully to her medication regimen and had remained asymptomatic. There was no absolute assurance, however, that she would never relapse. As a back-up safety plan, it was suggested that she could arrange a standby guardianship in which legal custody of her children would automatically, but temporarily, revert to someone else in the event of relapse and revert back to her when she was well.

The Risk of Violence Assessment revealed that Ms. C could engage in dangerous and violent behaviors when she became psychotic. She also had violent fantasies of killing herself and others when she was paranoid. However, she had never exhibited violent behavior when she was not psychotic, and she had no history of arrests or incarcerations. When she was not psychotic, Ms. C was not an angry or impulsive person. She also had no problems with substance abuse. Her husband did have a long history of addiction problems, however, which could potentially influence Ms. C's ability to parent. Nonetheless, by all accounts, Ms. C's husband had taken his addiction treatment seriously and was maintaining sobriety. Overall, Ms. C appeared to be at low risk for future violence. Ms. C has not yet regained custody of her child, so it is not known whether the assessment's prediction of low risk for child maltreatment was accurate.

Conclusions

Recent proposals to "fast-track" cases in the foster care system are important, as many children may spend prolonged periods in foster care before decisions are made about custody. Prolonged separations, especially when a child is young, can have a powerful and negative impact on long-term development and functioning (4,5). At the same time, careful consideration needs to be given to criteria that are used to determine how to fast-track foster care cases.

The three cases described in this paper all involved mentally ill mothers who had lost custody of their children because they had killed a person in the past. Using recently proposed categories of abuse (3), these cases would be fast-tracked by automatically terminating parental rights. On the other hand, when these cases were examined individually with standard risk assessment methodologies, the mothers were deemed to be at low risk for future child maltreatment and violence.

It should be underscored that long-term outcome data on the parenting capabilities of the mothers are not yet available. The decisions in the cases reviewed here should not be generalized to other cases, as each case presents its own dynamics and constellation of issues to be addressed.

Cases like these, however, call into question the assumption that all mentally ill individuals who have killed in the past are permanently incapable of caring safely for children and that parental rights should, therefore, be terminated automatically (3). The cases also illustrate the fact that decisions about the parenting competency of mentally ill individuals are rarely clear-cut.

Careful consideration needs to be given to how to fast-track cases that involve individuals with chronic and severe mental disorders. Assessments that are performed when an individual first enters the mental health system would allow a thorough evaluation and speed up any future decisions about child custody. At present, many individuals with severe and chronic mental disorders are evaluated several times over a long period using unsound methodologies that do not directly assess parenting competency or potential for violence (41). Use of comprehensive, sound assessments when a case first enters the system could help considerably in shortening the length of time that children of mentally ill parents remain in foster care.

Dr. Jacobsen is assistant professor of psychology in psychiatry and Dr. Miller is associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Address correspondence to Dr. Jacobsen at the Institute for Juvenile Research, Department of Psychiatry, 907 South Wolcott Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60612. This paper is one of several in this issue focused on women and chronic mental illness.

|

Table 1. Major domains and factors examined in the Parenting Risk Assessment and the Risk of Violence Assessment

1. Coverdale JH, Aruffo JF: Family planning needs of female chronic psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:1489-1491, 1989Link, Google Scholar

2. Miller U, Finnerty M: Sexuality, pregnancy, and childrearing among women with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services 47:502-596, 1996Link, Google Scholar

3. Murphy P: Diverting abuse cases from juvenile court: has the due process revolution gone too far? Chicago Bar Association Record, June-July 1996, pp 30-34Google Scholar

4. Bowlby J: Attachment and Loss, Vol 2: Separation: Anxiety and Anger. New York, Basic Books, 1973Google Scholar

5. Robertson J, Robertson J: Separation and the Very Young. London, Free Association Books, 1989Google Scholar

6. Peterson GH, Mehl LE: Some determinants of maternal attachment. American Journal of Psychiatry 135:1169-1173, 1978Google Scholar

7. Westheimer IJ: Changes in response of mother to child during periods of separation. Social Work 26:3-10, 1970Google Scholar

8. Pilowsky D: Psychopathology among children placed in family foster care. Psychiatric Services 46:906-910, 1995Link, Google Scholar

9. Apfel RJ, Handel MH: Madness and Loss of Motherhood: Sexuality, Reproduction, and Long-Term Mental Illness. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

10. Bowlby J: A Secure Base: Clinical Applications of Attachment Theory. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1988Google Scholar

11. Rogosch FA, Mowbray CT, Bogat A: Determinants of parenting attitudes in mothers with severe psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology 4:469-487, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Monahan J: Mental disorder and violent behavior. American Psychologist 47:511-521, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Monahan J, Steadman HJ (eds): Violence and Mental Disorder: Developments in Risk Assessment. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994Google Scholar

14. Cassell D, Coleman R: Parents with psychiatric problems, in Assessment of Parenting: Psychiatric and Psychological Contributions. Edited by Reder P, Lucey C. London, Routledge, 1995Google Scholar

15. Black D: Children of parents in prison. Archives of Disease in Childhood 67:967-970, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Jaffe PG, Wolfe DA, Wilson SK: Children of Battered Women. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1990Google Scholar

17. Quinsey V, Maguire A: Maximum security psychiatric patients: actuarial and clinical prediction of dangerousness. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 1:143-171, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Budd KS, Holdsworth M: Methodological issues in assessing minimal parenting competence. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 25:2-14, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Jacobsen T, Miller LJ, Kirkwood K: Assessing parenting competency in mentally ill individuals: a comprehensive service. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:189-199, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Reder P, Lucey C (eds): Assessment of Parenting: Psychiatric and Psychological Contributions. London, Routledge, 1995Google Scholar

21. Lidz C, Mulvey E, Gardner W: The accuracy of predictions of violence to others. JAMA 169:1007-1011, 1993Google Scholar

22. Steadman HJ, Monahan J, Appelbaum PS, et al: Designing a new generation of risk assessment research, in Violence and Mental Disorder: Developments in Risk Assessment. Edited by Monahan J, Steadman HJ. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994Google Scholar

23. Bowlby J: Attachment and Loss, Vol 1: Attachment. New York, Basic Books, 1982Google Scholar

24. Solomon J, George C: Defining the caregiving system: toward a theory of caregiving. Infant Mental Health Journal 17:183-197, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Crittenden PM: Relationships at risk, in Clinical Implications of Attachment. Edited by Belsky J, Nezworski T. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1988Google Scholar

26. George C, Solomon J: Representational models of relationships: links between caregiving and attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal 17:198-216, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Zeanah CH, Benoit D, Hirshberg L, et al: Classifying mothers' representations of their infants: results from structured interviews. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, San Francisco, Oct 1991Google Scholar

28. Azar ST, Robinson DR, Hekimian E, et al: Unrealistic expectations and problem-solving ability in maltreating and comparison mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 52:687-691, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Abidin RR: Parenting Stress Index (Short Form). Charlottesville, Va, Pediatric Psychology Press, 1990Google Scholar

30. Fink LA, Bernstein D, Handelsman L, et al: Initial reliability and validity of the Childhood Trauma Interview: a new multidimensional measure of childhood interpersonal trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1329-1335, 1995Link, Google Scholar

31. Amador XF, Strauss DH, Yale SA, et al: Assessment of insight in psychosis. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:863-879, 1993Google Scholar

32. Barrera M: Social support in the adjustment of pregnant adolescents: assessment issues, in Social Networks and Social Support. Edited by Gottlieb BH. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage, 1981Google Scholar

33. Jenner S, McCarthy G: Quantitative measures of parenting: a clinical-developmental perspective, in Assessment of Parenting: Psychiatric and Psychological Contributions. Edited by Reder P, Lucey C. London, Routledge, 1995Google Scholar

34. Caldwell BM, Bradley RH: Home Observation for the Measurement of the Environment: Administration Manual, rev. Little Rock, University of Arkansas Press, 1984Google Scholar

35. Kalichman SC: Disavowal of pregnancy: an adjustment disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:1620-1621, 1991Link, Google Scholar

36. Green AH, Power E, Steinbook B, et al: Factors associated with successful and unsuccessful intervention with child abusive families. Child Abuse and Neglect 4:45-52, 1981Google Scholar

37. Bayley N: Bayley Scales of Infant Development, 2nd ed. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corporation, 1993Google Scholar

38. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

39. Persson-Blennow I, Naeslund B, McNeil TJ, et al: Offspring of women with nonorganic psychosis: mother-infant interaction at one year of age. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 73:207-213, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Waldo MC, Roath M, Levine W, et al: A model program to teach parenting skills to schizophrenic mothers. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 32:1110-1112, 1987Google Scholar

41. Nicholson J, Geller JL, Fisher WH, et al: State policies and programs that address the needs of mentally ill mothers in the public sector. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:484-489, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar