Alcohol & Drug Abuse: Patient Satisfaction and Outcomes in Alcohol and Drug Abuse Treatment

Traditionally, the performance of a substance abuse treatment program has been measured during treatment by indicators of the program's ability to engage and retain patients and after treatment by measures of patient status, such as abstinence, employment, and use of health and social services. Although these measures offer a valid estimate of a treatment's effectiveness, outcome evaluations of this type are time consuming and costly (1).

With the increasing importance of the consumer movement and of continuous quality improvement in mental health and addiction treatment, evaluation has shifted toward measuring the performance of a treatment program in terms of clients' satisfaction with treatment. Besides offering a new perspective on performance, data on satisfaction are much easier for program administrators to collect, analyze, and utilize. Thus patient satisfaction measures have been emphasized in national performance evaluations (2,3).

In the course of completing an evaluation of four alcohol and drug abuse programs within the Kaiser Permanente system in northern California, we had an opportunity to compare three measures of treatment effectiveness_patient participation in treatment, patient status after treatment, and patient satisfaction. The results are reported in this column.

Methods

The four alcohol and drug abuse treatment programs evaluated were all well-established outpatient treatment programs staffed by licensed psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and counselors. All had an intensive phase of treatment consisting of approximately three months of three to five group therapy sessions a week and an aftercare phase consisting of approximately nine months of once-weekly group therapy. The intensive phase focused on patient education, introduction to 12-step recovery groups, and social support. Aftercare focused on supportive group therapy and encouraging attendance at 12-step groups. Disulfiram was available, but was infrequently prescribed.

The study patients were drawn from 525 adult admissions to the four programs between October 1991 and March 1992. No formal diagnostic interview was performed, but records indicated that all patients met DSM-IV criteria for abuse of or dependence on one or more substances. Of these patients, 435 (83 percent) signed a voluntary consent to participate in the study. Patients were offered no financial incentives but were assured that their participation would not affect their treatment status and that any information they provided would be kept confidential even from the program's treatment staff.

Patients were contacted by telephone at one, three, and six months after their intake interview. The contact rates were 83 percent (N=361) at one month, 81 percent (N=352) at three months, and 79 percent (N=344) at six months.

Three domains were measured at each follow-up interview. Treatment participation was operationally defined as the number of group therapy sessions and alcohol and drug education classes attended. Patient satisfaction with six aspects of treatment was assessed: the times treatment groups were held, the frequency and size of the treatment groups, the quality of the group therapists, and the program's overall quality, appropriateness, and effectiveness. Five response categories were provided: very unsatisfied, unsatisfied, neutral, satisfied, and delighted. They were scored from 1 to 5, with one indicating the least satisfaction, and scores for the six measures were summed for a total satisfaction score that could range from 6 to 30.

The third domain, patient performance, was measured in three areas using items from the Addiction Severity Index (4). They were self-reported number of days of use of alcohol and any type of illicit drug and the number and types of psychiatric symptoms experienced during the 30 days before each interview.

The major analyses were product-moment correlations among all measures of treatment participation, patient performance, and treatment satisfaction.

Results

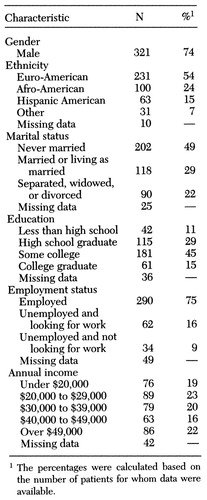

As Table 1 shows, about three-quarters of the sample were men, about half were white, half were married, three-quarters were employed, and almost 40 percent had an annual income above $40,000. The mean age of the sample was 37 years, and more than 60 percent had some education beyond high school.

The most common addiction problem was alcohol; 40 percent abused or were dependent on alcohol alone, and 47 percent had problems with cocaine or marijuana in addition to alcohol. More than 65 percent of the patients reported drinking more than five drinks a day. Only 13 percent had problems with illicit drugs only. The two most commonly used drugs were crack cocaine and marijuana. Comparisons across the four treatment sites showed that patients were similar on most variables measured.

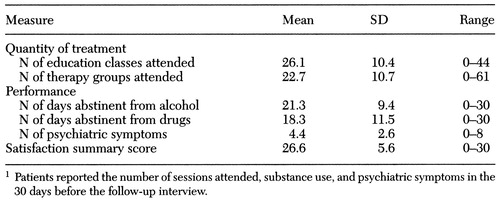

Table 2 presents sample means at six-month follow-up for patient performance measures_the number of days of drug and alcohol use and the number of psychiatric symptoms reported in the 30 days before the follow-up interview. All measures of drug and alcohol use and of psychiatric health showed significant improvements (p<.05) from admission to six months. Patients who completed the program showed significantly more improvement and better six-month outcomes than patients who attended only ten outpatient days of care. Those who completed ten days had significantly better results (p<.05) on all three measures than patients who dropped out within two visits.

Table 2 also reports the mean number of educational and therapy sessions attended by the patients during the 30 days before the six-month interview, and their mean satisfaction score.

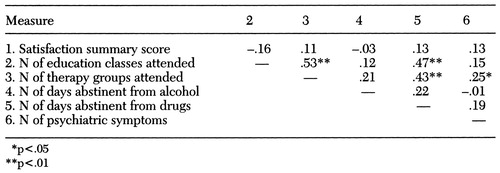

Table 3 shows the correlation matrix for the six measures in Table 2. Modest but significant correlations were found between both of the participation measures and the performance measures (p≤.10). However, no significant correlations were found between the satisfaction measure and the participation measures or the performance measures.

The same set of analyses was performed for data collected at the one- and three-month follow-ups, as well as separately for each treatment program. (Data collected at the follow-ups are available from the first author.) Although differences between analyses were noted, essentially the same type and level of relationships among the measures were found in each analysis. Finally, no statistically significant relationships were found (p>.10) between any of the individual satisfaction measures and the participation measures or the performance measures.

Discussion and conclusions

We examined three commonly measured aspects of addiction treatment effectiveness in four alcohol and drug treatment programs in a large health maintenance organization (HMO): patient participation in treatment, measured as the number of education and group therapy sessions attended; patient satisfaction with six aspects of treatment; and functional status, measured as the number of days of drug and alcohol use and the number of psychiatric symptoms reported at follow-up.

Patients varied substantially in their level of treatment participation and showed a corresponding range of reported improvements in alcohol and drug use and psychiatric symptoms. In contrast, uniformly high levels of satisfaction with the treatment process were reported, and levels of satisfaction were not well related either to participation measures or to performance measures.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the relationships between treatment participation, satisfaction, and outcome among patients in substance abuse treatment. Two other studies that investigated these relationships with general psychiatric patients also reported high levels of satisfaction among all patients sampled but only modest correlations between patient satisfaction and other performance and symptom measures (5,6).

Some limitations of this study should be highlighted. Although the HMO patients in the study are an important group, they are likely different in background characteristics from other groups of insured patients, and probably much different from publicly treated patients (7). In addition, a major consideration in all studies using self-report data is the reliability and validity of the information. First, the data were obtained from confidential interviews at admission and follow-up. Outcome status measures were taken from instruments and procedures that have been validated in many similar studies (4,7,8). As part of another study, after the six-month interview, 10 percent of the patients in our sample submitted urine samples for toxicology tests and underwent breath analysis. Less than 5 percent of self-reports about substance use were disconfirmed by these tests.

It is not possible to claim that no patients misrepresented their level of substance use. However, misrepresentation does not appear to explain why patients who reported continued drinking, drug use, or psychiatric symptoms were as likely to report satisfaction with their treatment as patients who reported low levels of substance use or symptoms or none at all.

The satisfaction measures were not tested for reliability or validity. However, the individual items were quite face valid, had clear response choices, and covered four of the domains suggested by two national accreditation agencies (2,3). They are the type of items that are widely used by similar programs, although standardized satisfaction measures would certainly have been preferable (9).

Some positive aspects of the study give us confidence in the results. The design was an intent-to-treat model; thus the findings are not restricted to patients who completed treatment. Second, the follow-up rates at each evaluation were over 80 percent, and the findings were quite similar for all three evaluations. The consistency of these results across time offers additional indication that the relationships are representative, at least in this population.

Although more than 80 percent of patients reported being "very satisfied" or "delighted" with virtually all aspects of their substance abuse treatment, no significant relationships were found between the satisfaction measure and either the participation or the performance measures at any follow-up point. In this regard, significant differences were found between those who completed treatment and those who dropped out within two weeks in abstinence rates and psychiatric symptoms, but not in satisfaction scores.

Although satisfaction is obviously an important consideration for managers and providers of addiction treatments, these data suggest that satisfaction measures may be a separate domain that should not be considered a proxy for improvement in symptoms or functioning.

Acknowledgments

Support for this work was received from the Permanente Medical Group and from ongoing research grants to the authors from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and Du Pont Merck Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. McLellan is affiliated with the Center for Addiction Studies of the department of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania and with the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Building 7, University Avenue, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Hunkeler is with the division of research at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, California. Richard J. Frances, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of 435 patients at entry into substance abuse treatment in a health maintenance organization

|

Table 2. Measures at six-month follow-up for 344 substance abuse patients in a health maintenance organization1

|

Table 3. Correlation matrix for six-month measures for 344 substance abuse patients in a health maintenance organizationMeasure23 456

1. Sederer L, Dickey B (eds): Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1995Google Scholar

2. Standards for Accreditation. Washington, DC, National Committee for Quality Assurance, 1995Google Scholar

3. Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Health Care Networks. Chicago, Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, 1995Google Scholar

4. McLellan AT, Cacciola J, Kushner H, et al: The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index: cautions, additions, and normative data. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 9:192-199, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Ankuta GY, Abeles N: Client satisfaction, clinical significance, and meaningful change in psychotherapy. Professional Psychology 24:71-74, 1993Google Scholar

6. Eisen SV: Client satisfaction and clinical outcomes: do we need to measure both? Behavioral Healthcare Tomorrow 5(4):71-73, 1996Google Scholar

7. McLellan AT, Weisner CM: Achieving the public health potential of substance abuse treatment: implications for patient referral, treatment "matching," and outcome evaluation, in Drug Policy and Human Nature. Edited by Bickel W, DeGrandpre R. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1995Google Scholar

8. Zanis D, McLellan AT, Randall M: Can you trust the self reports of drug users during treatment? Drug and Alcohol Dependence 22:31-35, 1995Google Scholar

9. Atkisson C, Zwick R: The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire: psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Evaluation and Program Planning 5:233-237, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar