Scheduled Intermittent Hospitalization for Psychiatric Patients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The effect of scheduled intermittent hospitalization on the hospital utilization, community adjustment, and self-esteem of persons with serious and persistent mental illness was examined in an experimental study. METHODS: Fifty-seven male veterans, aged 65 or younger, with a primary axis I psychiatric diagnosis who were frequent utilizers of inpatient care over the previous two years were randomly assigned to two groups. Patients in the experimental group were prescheduled for four hospital admissions, each lasting nine to 11 days, per year for two years. Patients in the control group had traditional access to hospital care. Psychiatric bed days, community adjustment, and self-esteem were assessed during and after the intervention. RESULTS: No differences between the groups on demographic or clinical variables were detected at study entry. The experimental group showed improvement in self-esteem, affect, and complaints of physical symptoms at one year. No statistically significant differences between groups were found in hospital utilization, financial management, substance abuse, or psychological well-being at one year. CONCLUSIONS: Scheduled intermittent hospitalization may be an appropriate and promising alternative to traditional care for revolving-door patients. This intervention could maintain patients at a higher level of wellness than traditional care and reduce the recurrence of the crises that precipitate hospitalization.

Numerous comprehensive community treatment programs have been designed and evaluated since the advent of deinstitutionalization, including brief and partial hospitalization, day treatment, long-term community residential treatment, and case management (1–8). Some persons with serious and persistent mental illness still frequently seek hospitalization and thus are at risk for becoming revolving-door patients dependent on institutional care (9,10). In the Department of Veterans Affairs health system and in other public systems, such patients utilize a disproportionately large share of bed days and health care resources (11,12).

Previous work has illustrated the importance of planning short admissions for persons with serious and persistent mental illness (13,14). Such intermittent hospitalization has been reported to be effective for elderly, physically ill patients (15), and respite care for patients with mental illness has been reported to be effective (16,17).

This paper describes an experimental study that explored the effects of scheduled intermittent hospitalization on the hospital utilization, community adjustment and self-esteem of patients with serious and persistent mental illness who had been admitted to the general psychiatry service of an urban VA medical center.

A potential barrier to implementation of scheduled intermittent hospitalization is the belief that the patients who would be admitted would not be sick enough to require hospitalization. However, despite the prevailing treatment paradigm that limits hospitalization to acute care admissions, acuteness of symptoms has not consistently been found to be the most significant predictor of psychiatric hospitalization (18–20). Other factors, such as denial of illness and satisfaction with family relationships, have also been shown to be significant predictors. Another potential barrier to implementation of scheduled intermittent hospitalization is the concern that the program would foster patients' dependency. However, as the intervention is designed for patients who already had high levels of inpatient utilization, the issue of dependency seems moot.

The conceptual framework for the experimental intervention in this project was self-care theory. Self-care is defined as behavior undertaken by an individual to promote health, prevent illness, or treat or cope with an illness (21). Self-care is not limited to prescribed treatment, and it involves attention to all aspects of daily life that influence health and stability. Self-care among persons with serious and persistent mental illness presents special challenges because they may have impaired cognitive functioning and may experience residual thought disturbances and accompanying affective dysfunction. For these patients, hospitalization is often precipitated by interpersonal and social disruption and exacerbation of symptoms associated with failure to follow treatment recommendations for effective self-care (22–24).

In this study, scheduled intermittent hospitalization was conceptualized as a supplement to self-care that would provide support and safe haven without disrupting the patient's life in the way emergency hospitalization sometimes does. In contrast to the sense of failure patients often experience when they are readmitted in crisis (25), reporting for and completing a scheduled period of treatment can provide patients with successful experiences in self-care. Such success may lead to increased self-esteem and improved clinical status. In addition, active participation in planning a scheduled hospitalization can bolster patients' autonomy.

At the same time, scheduled intermittent hospitalization provides families with respite from the burdens of care and thus promotes more positive attitudes toward the patient. Hospitals and staff may also benefit. Scheduled intermittent hospitalization decreases the unpredictable patient flow associated with crisis care. The planned and predictable hospital stays optimize bed usage and staffing, thereby increasing efficiency and decreasing cost. Moreover, scheduled intermittent hospitalization encourages labeling readmission as expected and thus may improve staff attitudes by decreasing feelings of failure, which are commonly thought to contribute to burnout (17).

This study targeted a patient group defined behaviorally by repeated use of psychiatric hospitalization. The treatment under study was the use of scheduled admissions versus unscheduled, emergency admissions, or standard care. We expected that participants in the scheduled intermittent hospitalization program would be hospitalized fewer days, have better community adjustment, and have higher self-esteem than comparable patients with traditional access to hospitalization.

Methods

All patients admitted to the general psychiatry service of an urban VA teaching hospital over the 21-month period from September 1988 to May 1990 were screened for eligibility for the study. Eligibility criteria were a primary psychiatric diagnosis; age 65 or younger; at least two admissions and 125 psychiatric inpatient days at this VA facility in the previous two years; lack of a DSM-III-R diagnosis of delirium, dementia, or mental retardation; and admission clearly not precipitated by unrelated medical problems. The area where the hospital was located had a large African-American population. Thus the study was able to focus on a minority group that is overrepresented in the population of frequently readmitted patients (26).

Self-esteem and community adjustment were measured at intake, at one year, and after the intervention had been terminated. The intervention was terminated at two years after discharge from the index admission. Self-esteem was measured using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE) (27). Five aspects of community adjustment—negative emotions, psychological well-being, financial management, physical symptoms, and substance abuse—were measured using the Personal Adjustment and Role Skills Scale (PAL-C) (28).

Although the initial study design included measurement of treatment group effect on psychopathology using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (29), these data were recognized as being confounded with planned versus emergency hospitalization. Thus only intake BPRS psychopathology scores were used as control variables. The RSE Scale, PAL-C, and BPRS are well known and were chosen for this study in part because their reliabilities and validities are well documented.

Psychiatric diagnosis was defined by a consensus rating by two trained interviewers after completion of an interview using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Lifetime Version (SADS-L) (30). Inpatient psychiatric days were tracked by patient reports and independently verified by records from facilities identified as having been used or likely to be used in the future. Psychiatric days were defined as any inpatient day in any psychiatric or substance abuse facility. Demographic and descriptive data were also collected.

We recognized that a large experimental effect would be necessary to render any future implementation of the intervention worthwhile. Power analysis (alpha=.05, power=.80) indicated that data for 60 subjects would be needed to enable 11 control variables to be entered into a regression model.

The study obtained approval of the institutional review board. Study procedures were fully explained to participants before study entry, and their written informed consent was obtained.

After intake data were collected, subjects were randomly assigned to two groups. Experimental subjects were scheduled for four admissions per year, each of which would last nine to 11 days, with intervals of 11 to 13 weeks between hospitalizations. The set length of scheduled hospitalizations obviated any issues of monetary secondary gain. To the extent possible, research staff scheduled hospitalizations to fit subjects' preferences. In addition to planned hospitalizations for experimental subjects, both groups could gain access to hospitalization through emergency admissions.

When hospitalizations occurred, experimental subjects and control subjects were admitted to one of three similar general psychiatric wards where they participated in individualized treatment programs designed by the multidisciplinary staff. For each patient, treatment included community ward meetings, meetings with a psychiatrist and primary nurse, group therapy, social work consultation and assistance with plans for follow-up care, attendance at Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous meetings if appropriate, and other therapeutic and recreational activities both on and off the ward. At study termination, limited data were collected on patients' perceptions of the receipt and usefulness of treatment services.

To maximize data collection during the two-year study period, as previously described (31), an extensive system of tracking and follow-up contacts at approximately monthly intervals was implemented. Because our primary focus was on utilization of psychiatric bed days, we believe the data on inpatient utilization are completely accurate. Given the more numerous sites from which patients may have received outpatient services, we were not as confident about the completeness of outpatient treatment utilization data, and they were not used for analytic purposes.

Total scale scores were calculated for each administration of the PAL-C, RSE, and BPRS. Internal consistency of the paper-and-pencil instruments was assessed by Cronbach's alpha, and interrater reliability for the BPRS by intraclass correlation. Group differences on psychological, demographic, and clinical variables at entry were assessed by t tests and c2 tests. Regression analysis was used to determine the association between the intervention and outcome variables after other variables had been controlled in a forced-entry regression model (Cohen's case 1) (32). The primary outcome variables were psychiatric bed days during a two-year period and scores on the PAL-C and RSE during the intervention (one year) and after the intervention (two years). Control variables that were applied to each dependent variable include the corresponding entry measure, qualifying bed days as a proxy for chronicity, entry BPRS as a proxy for severity of illness, and diagnosis (psychotic versus nonpsychotic). For analyses of data from the RSE and PAL-C, inpatient versus outpatient status was also added.

Results

A total of 1,640 patients admitted to the service over a 21-month period were screened for study eligibility. Of 84 patients who appeared initially to meet study criteria, seven were later excluded due to a primary diagnosis of dementia, inability to give informed consent, or inability to confirm an adequate number of hospital days. Only eight refused participation; the reason most frequently given was not wanting to participate in research. Two potential subjects left the hospital during the intake process. Thus 67 subjects completed initial data collection. One of these declined participation shortly after intake, and another died of undetermined causes. Of the 65 remaining patients, five died during the two-year study period, two from malignancies identified during the study and one each from a myocardial infarction, severe hypoglycemia, and an automobile accident. Three subjects proved unable or unwilling to participate in the experimental intervention and were dropped. In sum, 57 subjects—26 experimental subjects and 31 control subjects—completed the two-year protocol, and it is this sample for whom results are reported.

Once enrolled via intake data collection, attrition not due to death was minimal for this type of study. Data completion rates varied from 98 percent (N=56) on the majority of two-year measures to 65 percent (N=37) on the BPRS. Cronbach alphas ranged from .71 to .93 on subscales of the PAL-C, from .81 to .96 on the RSE, and from .80 to .85 on the BPRS; BPRS interrater reliabilities ranged from .88 to .92 (intraclass correlation) over the course of the study.

Subjects

The 57 participants were men ranging in age from 28 to 65 years. Their mean±SD age was 38.28±8.14 years. Most were African American (N=43) and had never married (N=56). Slightly more than half lived alone (N=32). No statistically significant differences were found between experimental subjects and control subjects on the intake characteristics of age, race, education, financial status, means of support, marital status, living situation, type of residence, stability of housing, and onset of illness.

All but four subjects completed the SADS interview and could be diagnostically classified according to Research Diagnostic Criteria. DSM-III-R diagnoses were substituted for these subjects. The diagnosis for 20 subjects was schizophrenia; for 15, schizoaffective disorder; for nine, major depression; for four, posttraumatic stress disorder; for three, bipolar disorder; for two, personality disorders without axis I disorders; and for one each, generalized anxiety disorder, impulse control disorder, organic mood disorder, and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified. All but two subjects also qualified for dual diagnoses of major psychiatric disorder and polysubstance abuse or dependence.

Although the minimum criterion for study entry was two hospitalizations, participants had been admitted numerous times (mean±SD=5.04± 2.20 hospitalizations). They had spent considerable time in the hospital (mean±SD=160.25±50.89 days) in the two years before entry into the study.

Hospital use

In keeping with the prescribed admission schedule, the 26 experimental subjects had a mean±SD of 9.31±3.45 admissions to psychiatric facilities, compared with 5.03±4.23 for control subjects. The number of supplementary unscheduled admissions for experimental subjects ranged from zero to eight (mean± SD=2.65±2.37). Five experimental subjects had no unscheduled admissions during the two-year study, and another five had one unscheduled admission.

Not all of the 26 experimental subjects were completely compliant with the protocol of eight scheduled admissions over the two-year period. Ten were 100 percent compliant, and only two were less than 50 percent compliant. Overall compliance with the 208 scheduled admissions was 77.4 percent. No significant differences between the experimental and control groups were found in subjects' perceptions of the types of treatment they received while in the hospital or the helpfulness of such treatment.

The regression model described was used to evaluate the hypothesis that scheduled intermittent hospitalization would decrease the number of psychiatric bed days used. Results indicated that this intervention was not a significant correlate of psychiatric bed days, either as a simple correlate or in the regression analysis. Experimental subjects used only slightly fewer inpatient days than control subjects (mean±SD=151.31±73.55 and 161.58±127.73, respectively).

During the two-year study period, three control subjects and two experimental subjects used inpatient care at other psychiatric facilities besides the VA facility. Thus there was little substitution for VA inpatient care, and most of the inpatient care received by the study subjects was provided at the study facility.

Patient outcomes

The impact of scheduled intermittent hospitalization on community adjustment and self-esteem was assessed at approximately one year (mean=373 days) after patients' discharge from their index admission. At the time of the assessment, 28 subjects were inpatients, and nine were outpatients.

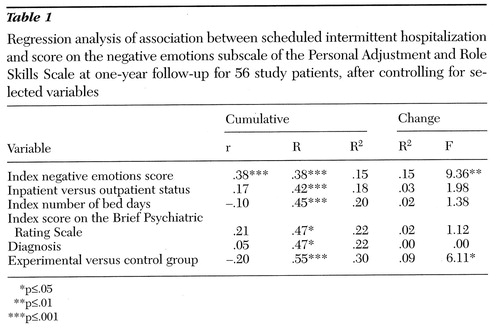

Using the regression procedure described, treatment group (experimental versus control) and negative emotions score at study entry were significantly correlated with the negative emotions score at one year. These results are shown in Table 1. Experimental subjects' negative emotions score decreased from a mean±SD of 17.46±2.58 at study entry to 13.69± 4.42 at one year, while the control subjects' scores remained essentially equivalent (mean±SD= 16.80±3.62 at entry compared with 15.57±4.75 at one year).

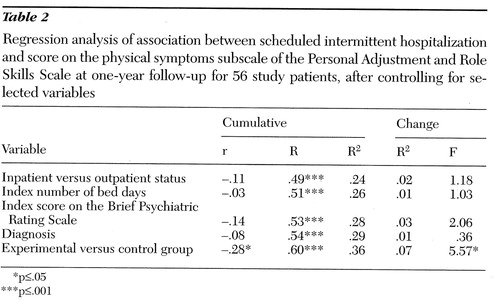

Similarly, initial and one-year physical symptom scores were significantly correlated, as Table 2 shows. More important, treatment group was significantly correlated with physical symptom scores, both as a simple correlate and after controlling for five other variables. Experimental subjects' physical symptom scores decreased from a mean±SD of 14.04± 3.93 at study entry to 11.89±4.11 at one year, while control subjects' scores remained the same (mean± SD=13.93±4.18 at study entry and 14.60±5.23 at one year).

At one year, with other variables controlled, treatment group was not a significant correlate of the other three community adjustment measures—substance use, psychological well-being, and financial management. However, a trend toward better psychological well-being in the experimental group was noted (p=.08).

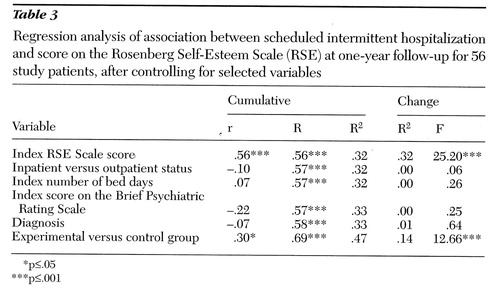

Using the same statistical model, treatment group was correlated with one-year self-esteem scores (see Table 3). Experimental subjects' self-esteem increased from a mean±SD of 24.42±5.87 at study entry to 29.73±7.29 at one year. Control subjects' self-esteem was unchanged (mean±SD=25.70±5.53 at study entry and 25.90±5.14 at one year).

To determine patients' perceptions of intermittent hospitalization, subjects were asked at the end of the study whether they preferred experimental or regular care. Significant group differences were noted (c2= 9.31, df=1, p=.002). Twenty-one experimental subjects and eight control subjects indicated a preference for scheduled intermittent hospitalization. Fourteen control subjects and four experimental subjects indicated no preference or a preference for traditional hospital access. Those who experienced the experimental intervention had a stronger preference for it than control subjects had for unscheduled hospitalization.

Discussion and conclusions

The study results suggest that scheduled intermittent hospitalization is a viable and promising alternative to traditional, crisis-oriented psychiatric hospitalization for frequent users of hospital care. Patients in both groups used about the same number of hospital days. However, experimental subjects had a significantly improved clinical outcome in self-esteem and complaints of negative emotions and physical symptoms.

During the study, the core themes of emergency hospitalization as failure and scheduled hospitalization as success were repeatedly noted by the patients themselves, by family members, and by treatment staff. It would appear that the accepted practice of reserving hospitalization or other more intensive treatment as a last resort—a practice strongly reinforced by contemporary managed care practices—may in fact negatively influence the well-being of persons with serious and persistent mental illness.

This interpretation is further supported by the finding that once the intervention was withdrawn, no statistically significant differences were observed in the clinical status of patients. If the two groups' approximately equal number of bed days are considered a partial proxy for cost, these results suggest that improved outcome may be achieved without additional inpatient costs. However, future research that measures both inpatient and outpatient costs will be necessary to definitively evaluate the relative differences.

It is noteworthy that although experimental subjects received notably easier access to hospitalization than did control subjects, treatment group was not a significant correlate of inpatient utilization. Experimental subjects could and did gain access to standard hospitalization in addition to scheduled hospitalization but used no more total hospital days than control subjects. This finding strongly suggests that some emergency hospitalization can be replaced with planned care.

On the other hand, ratings by experimental subjects of the importance of inpatient care confirm that it remains an essential component of the continuum of care for persons with serious and persistent mental illness. Further research should evaluate the optimal balance of scheduled and emergency hospitalization for this group. Another important area for future research is the applicability of scheduled intermittent hospitalization for other relapsing and frequently rehospitalized patients such as those with substance abuse or dependence or chronic medical conditions such as diabetes or congestive heart failure. Similarly, exploration of planned intermittent use of other relatively intense and costly services such as partial hospitalization and intensive outpatient services appears promising.

Five experimental subjects did not use any standard, crisis-related admissions during the two-year study period. Further, for the great majority of experimental subjects, having scheduled admissions seemed to decrease the need for unscheduled admissions. This pattern suggests that scheduled intermittent hospitalization can prevent some of the crises that lead to hospitalization of these patients.

The generalizability of these results is restricted by the use of one geographical site, the high proportion of African Americans in the study sample, and the inclusion of only male veterans in the sample. Research suggests, however, that men with schizophrenia have poorer clinical outcomes than women (33) and that the chronic patient population includes more male patients (34,35). Moreover, African Americans are proportionally overrepresented in the populations of both chronic mentally ill patients (36) and frequently readmitted patients (26). Although the study sample had a higher proportion of African Americans than would be found in other areas, race has generally not been found to be associated with relapse among chronic psychiatric patients (37,38).

When this study was initially proposed, it was questionable whether such severely ill patients would accept and comply with a program of scheduled intermittent hospitalization. In fact, acceptance of the program was reflected in the excellent compliance rate, as well as in patients' preference for scheduled hospitalization over standard care. Beyond the positive responses from the few families that were involved in the patients' treatment, scheduled intermittent hospitalization rather dramatically elicited more positive attitudes among the mental health staff. Staff set smaller and more realistic goals for these patients during each hospitalization and planned for patient treatment over successive admissions.

Considering the cost of inpatient care, its repeated use by a subgroup of patients with serious and persistent mental illness is an unwelcome fact. Alternative methods of delivering care need to be identified and explored, particularly in an era of increasing managed care. For selected patients, scheduled intermittent hospitalization appears to yield better clinical outcomes without additional inpatient cost. We suggest that scheduled intermittent hospitalization and planned intermittent episodes of other types of high-intensity care be further evaluated as a promising modality for mental health care.

As is often the case with the initial evaluation of a novel treatment technique, we have established only that scheduled intermittent hospitalization holds promise. Future research is necessary to determine its potential and to describe the specific patients for whom scheduled intermittent hospitalization and planned periods of other intensive services will be most valuable, as well as the specific conditions under which these interventions will be most successful.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Health Services Research and Development grants 87-021 and 90-904 from the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors thank Sue Hudec, Anna Alt-White, Kathleen Neill, Marty Shively, Kimberly Vivaldi, Angela Setzer, and Mary Callahan.

Ms. Dilonardo is a public health analyst for the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment in Rockville, Maryland. Dr. Connelly is professor and dean of the School of Nursing at Marymount University in Arlington, Virginia. Dr. Gurel and Dr. Seifert are independent health research consultants in Arlington, Virginia, and Chevy Chase, Maryland, respectively. Ms. Kendrick is a psychiatric clinical nurse specialist and Dr. Deutsch is chief of psychiatry services at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Washington, D.C. Address correspondence to Ms. Dilonardo at 19104 Olney Mill Road, Olney, Maryland 20832.

|

Table 1. Regression analysis of association between scheduled intermittent hospitalization and score on the negative emotions subscale of the Personal Adjustment and Role Skills Scale at one-year follow-up for 56 study patients, after controlling for selected variables

1*±.05

2**±.01

3***±.001

|

Table 2. Regression analysis of association between scheduled intermittent hospitalization and score on the physical symptoms subscale of the Personal Adjustment and Role Skills Scale at one-year follow-up for 56 study patients, after controlling for selected variables

1*±.05

3***±.001

|

Table 3. Regression analysis of association between scheduled intermittent hospitalization and score on the physical symptoms subscale of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE) at one-year follow-up for 56 study patients, after controlling for selected variables

1*±.05

3***±.001

1. Eckman TA, Wirshing WC, Marder SR, et al: Technique for training schizophrenic patients in illness self-management: a controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1549-1555, 1992Link, Google Scholar

2. Barofsky I, Connelly CE: Problems in providing effective care for the chronic psychiatric patient, in The Chronic Psychiatric Patient in the Community: Principles of Treatment. Edited by Barofsky I, Budson R. Jamaica, NY, SP Medical & Scientific, 1983Google Scholar

3. Bond GR, Miller LD, Krumweid RD, et al: Assertive case management in three CMHCs: a controlled study. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:411-418, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Chen A: Noncompliance in community psychiatry: a review of clinical interventions. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:282-286, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Arana JD, Hastings B, Herron E: Continuous care teams in intensive outpatient treatment of chronic mentally ill patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:503-507, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Hawthorne WB, Fals-Stewart W, Lohr JB: A treatment outcome study of community-based residential care. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:152-159, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Pang J: Partial hospitalization: an alternative to inpatient care. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 8:587-595, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Curtis JL, Millman EJ, Struening EL, et al: Effect of case management on rehospitalization and utilization of ambulatory care services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:895-899, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Bachrach LL: Asylum and chronically ill psychiatric patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 141:975-978, 1984Link, Google Scholar

10. Haywood TW, Kravitz HM, Grossman LS, et al: Predicting the “revolving door”phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:856-861, 1995Link, Google Scholar

11. Dilonardo J, Kendrick K, Seitz L: Use of inpatient psychiatric care at a VA medical center after implementation of a prospective payment system. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:939-942, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

12. Kivlahan DR, Heiman JR, Wright RC, et al: Treatment cost and rehospitalization rate in schizophrenic outpatients with a history of substance abuse. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:609-614, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Beebe LH: Reframe your outlook on recidivism. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health 28:31-33, 1990Google Scholar

14. Bryson K, Naqvi A, Callahan P, et al: Brief admission program: an alliance of inpatient care and outpatient case management. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health 28:19-23, 1990Google Scholar

15. Robertson D, Griffiths RA, Cosin LZ: A community based continuing care program for the elderly disabled: an evaluation of planned intermittent hospital readmission. Journal of Gerontology 32:334-339, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Geiser R, Hoche L, King J: Respite care for mentally ill patients and their families. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:291-295, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

17. Merchant DJ, Henfling PA: Scheduled brief admissions: patient "tuneups.” Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health 32:7-10, 1994Google Scholar

18. Kent S, Yellowlees P: Psychiatric and social reasons for frequent rehospitalization. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:347- 350, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

19. Postrado LT, Lehman AF: Quality of life and clinical predictors of rehospitalization of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:1161-1165, 1995Link, Google Scholar

20. Laessle R, Pfister HE, Wittchen HU: Risk of rehospitalization of psychotic patients: a 6-year follow-up investigation using the survival approach. Psychopathology 20:48- 60, 1987Google Scholar

21. Connelly CE: Self-care and the chronically ill patient. Nursing Clinics of North America 22:621-628, 1987Medline, Google Scholar

22. Connelly CE, Davenport YB, Nursberger J: Adherence in a lithium carbonate clinic. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:585-588, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Green JH: Frequent rehospitalization and noncompliance with treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:963-966, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

24. Lyons JS, O'Mahoney MT, Miller SI, et al: Predicting readmission to the psychiatric hospital in a managed care environment: implications for quality indicators. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:337-340, 1997Link, Google Scholar

25. Lally SJ: Does being in here mean there is something wrong with me? Schizophrenia Bulletin 15:253-265, 1989Google Scholar

26. Havassy BE, Hopkin JT: Factors predicting utilization of acute psychiatric inpatient services by frequently hospitalized patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:820-823, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

27. Rosenberg M: Conceiving the Self. New York, Basic Books, 1979Google Scholar

28. Ellsworth RB: Measuring Personal Adjustment and Role Skills. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1981Google Scholar

29. Hedlund J, Vieweg B: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): a comprehensive review. Journal of Operational Psychiatry 11:48-65, 1980Google Scholar

30. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: Use of the Research Diagnostic Criteria and the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia to study affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 136:52-56, 1979Link, Google Scholar

31. Dilonardo J, Kendrick K, Vivaldi KB: Chronic or long-term psychiatric patients: potential subjects for longitudinal research. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 14:109- 118, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Cohen J: Statistical Analyses for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1988Google Scholar

33. Shepherd M, Watt D, Falloon I, et al: The natural history of schizophrenia: a five-year follow-up study of outcome and prediction in a representative sample of schizophrenics. Psychological Medicine 15(suppl):1-46, 1989Google Scholar

34. Goldstein JM: Gender differences in the course of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:684-689, 1988Link, Google Scholar

35. Thornicroft G, Gooch C, Dayson D: Readmission to hospital for long-term psychiatric patients after discharge to the community. British Medical Journal 305:996-998, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Susser E, Struening EL, Conover S: Psychiatric problems in homeless men: lifetime psychosis, substance use, and current distress in new arrivals at New York City shelters. Archives of General Psychiatry 46:845-850, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Serban G, Gidynski CB: Significance of social demographic data for rehospitalization of schizophrenic patients. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 15:117-126, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Miller GH, Willer B: Predictors of return to a psychiatric hospital. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 44:898-900, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar