Clozapine Therapy for Older Veterans

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The effectiveness of clozapine treatment in a treatment-refractory sample of older adult veterans with primary psychosis was examined. METHODS: Data were collected over a five-year period for patients age 55 and older who were given clozapine because of a history of treatment-refractory or treatment-intolerant psychosis. At initiation of clozapine therapy, baseline demographic, clinical, and psychopathology data were collected. At baseline and quarterly, patients' psychopathology was rated with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), and involuntary movements were rated with the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS). RESULTS: The 329 patients age 55 or older who received clozapine during the study period represented 10 percent of all patients on clozapine therapy in the VA system. Of the 312 patients for whom demographic information was available, 294 were men and 18 were women. Overall, patients improved on clozapine therapy, although wide variation in drug response was observed. Complete BPRS and AIMS data were available for 97 patients. The 55- to 64-year-old group had a mean improvement in total BPRS score of 19.8 percent, with 42.6 percent showing more than a 20 percent improvement; those age 65 and older had a mean improvement of 5.7 percent, with 17.2 percent showing an improvement greater than 20 percent. The 97 patients with complete AIMS data showed a mean improvement of 16.6 percent in total score. CONCLUSIONS: Clozapine is an important therapeutic agent for older adults with treatment-refractory psychosis. Patients between the ages of 55 and 64 may have a better response than those age 65 and older.

Elderly persons with serious mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder, often have severe debilitating illness associated with intensive use of health services and high costs. Thirty-five percent of elderly patients hospitalized in public psychiatric facilities and up to 12 percent of nursing home residents have schizophrenia or primary psychotic disorders (1,2). With increased life expectancy, the number of elderly individuals is rapidly increasing (3). The number of individuals with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses may thus also be expected to increase.

The Veterans Health Administration is a major provider of services to veterans with severe mental illness, which affects between 405,000 and 630,000 U.S. veterans. Individuals age 55 years and older represent approximately a third of the total veteran population with severe mental illness (4). In 1993 the VA spent approximately $1.3 billion for inpatient care of seriously mentally ill patients and more than $223 million on outpatient care (4). Elderly veterans with severe mental illness extensively utilize hospital-based services (5).

Although older patients with schizophrenia generally improve with antipsychotic therapy (6), therapeutic interventions with elderly individuals must consider age-related changes in physiology, medical comorbidity, and altered response to psychotropic medications. Compared with young adults, older adults with schizophrenia have a greater prevalence of both acute and chronic extrapyramidal syndromes (7) and may have a sixfold-higher prevalence of tardive dyskinesia (6,8).

Some investigators have reported that older adults with schizophrenia have a gradual decrease of positive symptoms and a worsening of negative symptoms (9,10,11). Negative symptoms may respond less well to antipsychotic therapy than positive symptoms (12). Patients with late-onset schizophrenia may also be particularly less responsive to antipsychotic therapy (13), which suggests that treatment resistance or treatment intolerance may be an even greater concern in older adult populations than in young adults with schizophrenia.

The atypical antipsychotic clozapine has superior efficacy in patients who have suboptimal response to conventional antipsychotic medications, may have superior efficacy for treating negative symptoms, and does not appear to cause tardive dyskinesia (14). Although clozapine has been reported to be generally successful in treating the psychosis associated with Parkinson's disease (15,16,17,18,19,20,21), far fewer data exist on experience with clozapine among elderly patients with primary psychosis (22,23,24,25,26). Although reports suggest that clozapine may be effective in management of late-life psychosis, issues such as range of drug dosing, tolerability, and quantified treatment response remain unclear. A number of authors have cited the need for more extensive data on clozapine use among older adults (23,24,27).

In light of the severe functional impairment of older adults with severe mental illness, their high service needs, and the high costs of treating them, it is imperative that all promising technologies for the treatment and rehabilitation of this population be explored. The goal of this study was to add information to the limited database on clozapine therapy for older adults by assessing outcomes of clozapine therapy among older adult veterans and examining differences in response to clozapine within the older adult population.

Methods

The data for this study were collected by the VA National Clozapine Coordinating Center as part of a quality assurance protocol for management of patients on clozapine therapy. Data were collected from October 1, 1991, to March 1, 1996. Indications for use of clozapine required either a history of treatment-refractory psychosis, defined as failure of trials of at least two traditional neuroleptics for at least six weeks in dosages of 1,000 mg of chlorpromazine equivalents a day, or intolerance to conventional neuroleptics, defined as severe disability due to extrapyramidal syndromes or severe tardive dyskinesia.

Baseline demographic, clinical, and psychopathology data were collected by the treatment team through patient interview and chart review. Within four weeks after clozapine therapy was started, patients' psychopathology was rated with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (28), and involuntary movements were rated with the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) (29). The BPRS and AIMS were readministered quarterly. The clozapine dosage and titration schedule were determined by the treating physician, based on the patient's clinical status.

For this study, a computer search of the electronic national VA clozapine database was done for all older adults on clozapine therapy. These individuals were grouped into two categories: patients between the ages of 55 and 64 and those age 65 and older. Moeller and associates (30) found that the risk of clozapine discontinuation increased in a population of male veterans on clozapine therapy when age increased by ten years. Change in psychopathology was determined by comparison of the baseline BPRS score and the score at termination or at the time of the last BPRS administration.

Differences in response to clozapine between the two age groups were compared using t tests and chi square analysis, as appropriate, and repeated-measures analysis of variance with a grouping variable. The analysis used age (55 to 64 years, and 65 years and older) as the between-subject factor and time (baseline and endpoint) as the within-subject factor.

Results

Treatment distribution

The search found that 3,249 patients received clozapine therapy in a network that included 168 VA facilities. The frequency of clozapine prescription varied widely among the VA sites. A number of sites had no patients on clozapine, and some had more than 100 patients on clozapine. A total of 329 patients age 55 years or older were on clozapine. This group accounted for 10.1 percent of all patients on clozapine therapy in the VA system.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

The mean±SD age of the total group (N=329) was 63.4±6.5 years, with a range of 55 to 86 years. Racial composition of the group of 310 patients for whom race data were available was 270 Caucasians (86.5 percent), 33 African Americans (10.6 percent), five Hispanics (1.6 percent), and two individuals of other or unknown race (1.2 percent). Additional demographic and clinical data were available for 312 of the 329 patients. The sample comprised 294 men (94.2 percent) and 18 women (5.8 percent).

Most of the patients had a diagnosis of schizophrenia (267 patients, or 85.6 percent), while a smaller number had other psychotic conditions (45 patients, or 14.4 percent). Overall, patients were severely symptomatic and often had been chronically institutionalized. In most cases, patients had positive symptoms of schizophrenia at baseline, such as conceptual disorganization (253 patients, or 81.1 percent), suspiciousness (225 patients, or 72.1 percent), hallucinations (236 patients, or 75.6 percent), and unusual thought content (236 patients, or 75.6 percent). Most patients had a history of a suicide attempt (211 patients, or 67.6 percent), and 11 patients (3.5 percent) had attempted suicide in the month before beginning clozapine.

A total of 156 patients (50 percent) had a history of assaults on others, and 65 (20.8 percent) were assaultive in the month before beginning clozapine. Most patients were hospitalized at the time of clozapine initiation (256 patients, or 82.1 percent), while only 49 (15.7 percent) were outpatients. Information about the treatment setting was not available for seven patients (2.2 percent). Most patients (213 patients, or 68.3 percent) reported extrapyramidal symptoms, with dystonia present in 26.9 percent of cases (84 patients), akathisia in 45.5 percent (142 patients), and tardive dyskinesia in 55.4 percent (73 patients).

Information about comorbid medical illness was available for 208 patients. The most common comorbid medical illnesses were hypertension (26 patients, or 12.5 percent of those for whom data were available), diabetes (14 patients, or 6.7 percent), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (11 patients, or 5.3 percent), arthritis (nine patients, or 4.3 percent), and peptic ulcer disease (seven patients, or 3.4 percent).

In this group of older adults, 201 (64.4 percent) were in the 55- to 64-year age group, and 111 (35.6 percent) were in the age group 65 years and older. The mean±SD age of the younger group was 59.3±2.8 years, with a range of 55 to 64 years. In the older group, the mean±SD age was 70.8±4.3 years, with a range of 65 to 86 years.

Drug dosage and adverse effects

The mean±SD duration of clozapine therapy was 278±266 days, with a range of two to 1,379 days. The mean± SD clozapine dosage was 310±223 mg a day, with a range of 12.5 to 900 mg a day. At the end of the study, 172 patients (55.1 percent) were receiving ongoing clozapine therapy. Clozapine therapy had been discontinued for 134 patients (42.9 percent), and treatment status was not reported for six patients (1.9 percent). No significant difference was found between the two age groups in the number of patients remaining on clozapine therapy and the number for whom therapy was discontinued.

Reasons for discontinuing clozapine were available for 107 patients. The most common reason was administrative problems (32 patients, or 29.9 percent of patients for whom data were available); for example, the patient was transferred to another hospital, or the distance from the patient's home was too great for follow-up visits. Other reasons were poor drug response (19 patients, or 17.8 percent), patient noncompliance (17 patients, or 15.9 percent), central nervous system side effects such as sedation (12 patients, or 11.2 percent), hematologic side effects (seven patients, or 6.5 percent), and cardiovascular side effects such as hypotension and tachycardia (six patients, or 5.6 percent). Hematologic side effects included neutropenia with white blood cell counts greater than 2,000 in three cases (2.8 percent), neutropenia with counts less than 2,000 in two cases (1.9 percent), and agranulocytosis in two cases (1.9 percent). Five deaths occurred, with three deaths clearly related to underlying medical illness and two deaths of unclear etiology, apparently due to acute cardiovascular events. There were no reported suicides in the group.

Therapeutic response

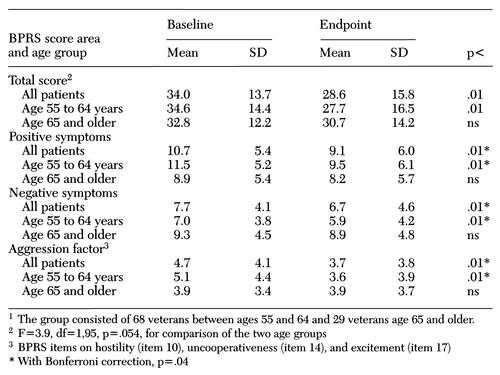

Overall, the sample improved on clozapine therapy; however, wide variation was noted in drug response. Mean BPRS scores at baseline and endpoint (last available BPRS rating) for both age groups are summarized in Table 1. Baseline and endpoint BPRS scores were available for 97 patients. Endpoint was defined as the most recent score for patients receiving clozapine and the score at treatment termination for patients for whom clozapine was discontinued. The group of 97 patients had a mean percentage change in BPRS score of 15.6 percent. The 55- to 64-year-old group had a mean improvement of 19.8 percent in total BPRS score, while the group age 65 and older had a mean improvement of 5.7 percent.

For the 97 patients with complete BPRS data, the interaction between group and time was nearly statistically significant (F=3.8, df=1,95, p=.054). In the 55- to 64-year-old group, 29 patients (42.6 percent) showed a 20 percent improvement in total BPRS score, while in the older group five patients (17.2 percent) showed an improvement greater than 20 percent (χ2=5.8, df=1, p=.02). BPRS scores indicated that both groups improved more in positive symptoms than in negative symptoms. Although the improvement in positive symptoms was greater in the 55- to 64-year-old group, the interaction failed to reach statistical significance.

The changes in mean score on BPRS items indicative of aggression (hostility, uncooperativeness, and excitement) also indicated improvement for the group of 97 patients with complete BPRS data. The only difference between age groups was that paranoid symptoms in the 55- to 64-year-old group improved significantly more than in the older group (F=6.2, df= 1,95, p=.01; with Bonferroni correction, p=.04). The proportion of patients in treatment-resistant and treatment-intolerant categories did not account for the statistically significant differences between age groups in change in BPRS scores.

Improvements in symptoms of movement disorders were noted. Baseline and endpoint AIMS scores were available for 97 patients. Patients age 65 years and older had the highest level of symptoms of movement disorders at baseline, with a mean±SD AIMS score of 9.4±7.5, compared with a mean score of 6.2±5.8 in the younger group (F=5.5, df=1,95, p=.02). The endpoint mean scores were 4.4±5.9 for the younger group and 7.5±6.5 for the older group. The endpoint difference between groups was not significant. The group of 97 patients had a mean improvement of 16.6 percent in AIMS score.

Discussion and conclusions

Overall, the sample of veterans improved on clozapine therapy. The study is limited primarily by the incomplete database and the study's open-label, noncontrolled nature. Although findings must be interpreted with caution, some observations about use of clozapine among older adults within a large public health care system may be made. Because this was a veteran sample and predominantly male, findings may not be generalizable to populations with a more heterogeneous gender representation.

Clinical characteristics

The population was characterized by a high level of behavioral symptoms—50 percent of patients had a history of assaultiveness, and 20.8 percent had been assaultive in the month before beginning clozapine therapy. Nearly all were hospitalized at the time of clozapine initiation. A high prevalence of extrapyramidal symptoms was noted, which might be expected from the chronic neuroleptic exposure experienced by this very ill population.

Drug dosage and adverse effects

Clozapine dosage in this sample of older adults with primary psychosis was substantially higher than clozapine dosages reported in samples of older adults with nonprimary psychosis, such as Parkinson's disease or vascular dementia with psychotic features (19,20,21,24); daily dosages among the latter groups are generally 100 mg or less. Chengappa and associates (23) reported that rapid titration of clozapine to a target dose of 300 mg a day in elderly patients is likely to lead to drug intolerance and poor outcome, while slow and gradual titration is likely to lead to improved drug tolerance and good outcome.

Compared with the private sector, less intense pressure was felt at inpatient VA settings during the study period to rapidly medicate and discharge patients. It is possible that the VA population was able to tolerate higher doses of clozapine due to very slow upward titration. A previous study found that clozapine titration in elderly VA inpatients may take up to 90 days (26).

More than half of patients in this sample were able to continue active clozapine therapy. The discontinuation rate (43 percent) was only slightly higher than the rates of 35 to 39 percent cited by other investigators reporting on younger adult populations (31,32,33). Data on reasons for discontinuation of clozapine therapy were available for 107 cases in which therapy was discontinued. The most common reasons were administrative (including noncompliance) in 45.9 percent of cases, followed by medication side effects in 23.4 percent of cases and poor drug response in 17.8 percent.

Moeller and coworkers (30) found similar reasons for discontinuation in a larger, broader-population sample of veterans on clozapine therapy. In that study 44 percent of patients were discontinued for administrative reasons, including noncompliance; 27.7 percent were discontinued because of side effects; and 21.7 percent were discontinued because of poor drug response.

Agranulocytosis occurred in two patients (1.9 percent), but neither case resulted in death. Estimated rates of agranulocytosis in clozapine-treated populations have ranged from .5 percent to 2 percent (34,35,36,37,38). Alvir and associates (39) more recently reported that .8 percent of patients treated with clozapine will develop agranulocytosis and that agranulocytosis risk increases with age (40). We concur with Alvir and Lieberman (40) that the hematologic monitoring system is both necessary and effective during clozapine therapy.

Therapeutic response

Despite severe treatment-refractory behavioral symptoms and a high prevalence of extrapyramidal symptoms, this older adult population improved on clozapine therapy. For the 97 patients for whom complete BPRS data were available, a trend was noted for the 55- to 64-year-old group to have a greater degree of improvement than the group age 65 and older. Patients' positive symptoms improved more than their negative symptoms. As reported by others, positive symptoms generally respond well to clozapine therapy (8,41).

The percentage of patients who improved to a significant clinical extent—greater than 20 percent improvement in BPRS score—is somewhat surprising in this extremely ill, treatment-refractory older population. For patients with complete data, nearly half of those in the 55- to 64-year-old group and nearly 20 percent of those age 65 and older showed significant clinical improvement. Other investigators have reported response rates to clozapine for younger populations ranging from 30 to 60 percent (8,42).

Patients' extrapyramidal symptoms also improved. Given the high prevalence of such symptoms in the older adult population (7), this finding supports previous reports that clozapine is indicated in treating refractory psychosis with tardive dyskinesia (43,44).

The database did not provide information about how improvements in psychotic symptoms and movement disorders may have led to improved quality of life. However, a previous study of a smaller group of older adults in the VA system found that successful response to clozapine therapy was associated with a greater ability to be discharged from chronic institutional settings (26). For example, even relatively modest changes in behavioral symptoms may allow a patient with severe schizophrenia to be discharged from a locked psychiatric facility to a nursing home, group home, or other less restrictive setting.

Overall improvement in scores on BPRS items indicating aggression suggest that the high degree of assaultiveness in this population was reduced by clozapine therapy. Volavka and coworkers (45) reported that clozapine therapy may be associated with reduction in the number of aggressive incidents in a state hospital system. The absence of any suicides in this study over a five-year period supports the report by Meltzer and Okayli (46) that clozapine may decrease suicidality.

In summary, clozapine is an important therapeutic agent for use with severely ill older adults with treatment-refractory psychosis. Institutions or health care systems that treat severely and chronically mentally ill older adults should promote administrative policies that permit use of all appropriate antipsychotic therapies. It is also crucial to provide education to staff, patients, and families on the use of all available options for management and treatment of psychosis in this population.

Acknowledgments

This material is based on work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors thank Richard McCormick, Ph.D., for helpful suggestions.

Dr. Sajatovic and Dr. Ramirez are affiliated with the Cleveland Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 10000 Brecksville Road, Brecksville, Ohio 44141, and, with Dr. Thompson, are also affiliated with the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. Dr. Garver and Mr. Ripper are with the Dallas VA Medical Center. Dr. Garver is also affiliated with the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas. Dr. Lehmann is with the VA Mental Health Strategic Healthcare Group at the VA Central Office in Washington, D.C., and the Georgetown University School of Medicine.

|

Table 1. Mean scores on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) of older veterans1 at the initiation of clozapine therapy (baseline) and at the last BPRS administration or at discontinuation of clozapine (endpoint)

1. Gurland BJ, Cross PS: Epidemiology of psychopathology in old age: some implications for clinical services. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 5:11-26, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Tariot PN, Podgorski CA, Blazina L, et al: Mental disorders in the nursing home: another perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1063-1069, 1993Link, Google Scholar

3. Malmgren R: Epidemiology of aging, in Textbook of Geriatric Neuropsychiatry. Edited by Coffey CE, Cummings JL. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

4. Special Committee for Seriously Mentally Ill Veterans: First Annual Report to the Undersecretary for Health. Washington, DC, Department of Veterans Affairs, 1995Google Scholar

5. Sajatovic M, Popli A, Semple W: Health resource utilization over a ten-year period by geriatric veterans with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services 47:961-965, 1996Link, Google Scholar

6. Jeste DV, Lacro JP, Gilbert DL, et al: Treatment of late-life schizophrenia with neuroleptics. Schizophrenia Bulletin 19:817-827, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Smith JM, Baldessarini RJ: Changes in prevalence, severity, and recovery in tardive dyskinesia with old age. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:1368-1373, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Kane JM, Woerner M, Lieberman J: Tardive dyskinesia: prevalence, incidence, and risk factors. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 8:525-565, 1988Google Scholar

9. Hoffman WF, Ballard C, Turner EH, et al: Three-year follow-up of older schizophrenics: extrapyramidal syndromes, psychiatric symptoms, and ventricular brain ratio. Biological Psychiatry 30:913-926, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Ciompi L: Aging and schizophrenic psychosis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 71(suppl 319):93-105, 1985Google Scholar

11. Davidson M, Harvey PD, Powchick P, et al: Severity of symptoms in chronically institutionalized geriatric schizophrenic patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:197-207, 1995Link, Google Scholar

12. Crow TJ: Molecular pathology of schizophrenia: more than one disease process? British Medical Journal 280:66-68, 1980Google Scholar

13. Tran-Johnson TK, Krull AJ, Jeste DV: Late-life schizophrenia and its treatment: pharmacologic issues in older schizophrenic patients. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 8:401-410, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Baldessarini RJ, Frankenburg FR: Clozapine: a novel antipsychotic agent. New England Journal of Medicine 324:746-753, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Scholz E, Dichgans J: Treatment of drug-induced exogenous psychosis in parkinsonism with clozapine and fluperlapine. European Archives of Psychiatry and Neurological Science 235:60-64, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Friedman JH, Max J, Swift R: Idiopathic Parkinson's disease in a chronic schizophrenic patient: long-term treatment with clozapine and L-dopa. Clinical Neuropharmacology 10:470-475, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Pakkenberg H, Pakkenberg B: Clozapine in the treatment of tremor. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 73:295-297, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Ostergaard K, Dupont E: Clozapine treatment of drug-induced psychotic symptoms in late stages of Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 78:349-350, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Factor S, Brown D: Clozapine prevents recurrence of psychosis in Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders 7:125-131, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Wolters EC, Hurwitz TA, Mak E, et al: Clozapine in the treatment of parkinsonian patients with dopaminergic psychosis. Neurology 40:832-834, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Oberholzer AF, Hendricksen C, Monsch AV, et al: Safety and effectiveness of low-dose clozapine in psychogeriatric patients: a preliminary study. International Psychogeriatrics 4:187-195, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Frankenburg FR, Kalunian D: Clozapine in the elderly. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 7:129-132, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Chengappa KN, Baker RW, Kreinbrook SB, et al: Clozapine use in female geriatric patients with psychosis. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 8:12-15, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

24. Pitner JK, Mintzer JE, Pennypacker LC, et al: Efficacy and adverse effects of clozapine in four elderly psychotic patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 56:180-185, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

25. Salzman C, Vaccaro B, Lieff J, et al: Clozapine in older patients with psychosis and behavioral disruption. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 3:26-33, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Sajatovic M, Jaskiw G, Konicki PE, et al: Outcome of clozapine therapy for elderly patients with refractory primary psychosis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 12:553-558, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Salzman C: Clozapine in elderly psychotic patients (ltr). Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57:309, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

28. Overall JE, Gorham D: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799-812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Guy W: ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopathology. Pub (ADM) 76-338. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1976Google Scholar

30. Moeller FG, Chen Y, Steinberg JL, et al: Risk factors for clozapine discontinuation among 805 patients in the VA hospital system. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 7:167-173, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Meltzer HY, Cola P, Way L, et al: Cost effectiveness of clozapine in neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1630-1638, 1993Link, Google Scholar

32. Revicki DA, Luce BR, Weschler JM, et al: Cost-effectiveness of clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:850-854, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

33. Lindstrom LH: The effect of long-term treatment with clozapine in schizophrenia: a retrospective study in 96 patients treated with clozapine for up to 13 years. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 77:524-529, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Idanpaan-Heikkla J, Alhava E, Olkinuora M, et al: Agranulocytosis during treatment with clozapine. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 11:193-198, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Griffith RW, Saameli K: Clozapine and agranulocytosis (ltr). Lancet 2:657, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Amsler HA, Teerenhovi L, Barth E, et al: Agranulocytosis in patients treated with clozapine: a study of the Finnish epidemic. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 56:241-248, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Anderman B, Griffith RW: Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis: a situation report up to August 1976. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 11:199-201, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. De la Chapelle A, Kari C, Nurminen M, et al: Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis: a genetic and epidemiologic study. Human Genetics 37:183-194, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Alvir JM, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, et al: Clozapine-induced risk factors in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 329:152-156, 1993Google Scholar

40. Alvir JM, Lieberman JA: Agranulocytosis: incidence and risk factors. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 55(suppl 9B):137-138, 1994Google Scholar

41. Small JG, Milstein V, Marhenke JD, et al: Treatment outcome with clozapine in tardive dyskinesia, neuroleptic sensitivity, and treatment-resistant psychosis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 48:263-267, 1987Medline, Google Scholar

42. Meltzer HY, Burnett S, Bastani B, et al: Effects of six months of clozapine treatment on the quality of life of chronic schizophrenic patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:892-897, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

43. Tamminga CA, Thaker GK, Moran M, et al: Clozapine in tardive dyskinesia: observations from human and animal model studies. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 55:(suppl 9B):102-106, 1994Google Scholar

44. Gerlach J, Peacock L: Motor and mental side effects of clozapine. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 55(suppl 9B):107-109, 1994Google Scholar

45. Volavka J, Zito J, Vitrai J, et al: Clozapine effects on hostility and aggression in schizophrenia (ltr). Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 13:287-289, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Meltzer HY, Okayli G: Reduction of suicidality during clozapine treatment of neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia: impact of risk-benefit assessment. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:183-190, 1995Link, Google Scholar