Increased Contact With Community Mental Health Resources as a Potential Benefit of Family Education

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the hypothesis that families of adults with severe mental illness who participate in either a group family education workshop or individual family consultation will try to seek more assistance from community services than those in a control group assigned to a waiting list. METHODS: A total of 225 family members who agreed to participate in the study were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: a ten-week group workshop, individual family consultation, or a waiting list (control group). Family members were interviewed about the extent of their contact with mental health professionals, providers, and community resources at baseline, termination of the interventions, and at six months after termination. RESULTS: No differences were found between conditions in the extent of family members' contact with three types of services: conventional, psychosocial, and ancillary mental health services. CONCLUSIONS: Neither of the educational interventions produced any change in behaviors of families seeking advice and assistance on behalf of their ill relative from the three types of services examined. Modifications in the interventions may be worthwhile. Increasing family members' contacts with community resources on behalf of their ill relative may increase the benefits of the intervention to the family as well as to the ill relative.

Families of adults with severe mental illness are a primary resource for their ill relative since the advent of deinstitutionalization. They often provide housing, financial aid, emotional support, and informal case management (1,2). They assume these responsibilities while hampered by limited knowledge of the disorder and available resources, minimal support, and virtually no training in coping skills and problem-solving strategies. The realities of the disorder compounded by the consequences of managing the illness result in enormous family burden and stress (3). Families, therefore, need information, support, education, and skill training to cope and reduce their burden.

Families of adults with severe mental illness generally value the services provided to their relative by the mental health system (4). However, when it comes to their own needs as family members, they have been far less satisfied. Families have reported dissatisfaction with their level of involvement in their relative's treatment, and they often feel left out of the treatment process. Family members frequently report that their interactions with mental health providers leave them feeling guilty, frustrated, and helpless (5,6,7).

Bernheim and Switalski (7) found that families desired more information than was provided. Families were frequently not involved in treatment planning and not informed of changes in the treatment or location of their relative or how to handle the symptoms and behaviors of the illness. Families desired more skills to cope with the illness, such as behavior management, medication monitoring, and dealing with other family members about the relative's illness.

Similarly, in a study of families whose relatives were recently released from a state hospital that was being closed, Solomon and Marcenko (8) found the greatest areas of dissatisfaction were lack of discussion of future plans for their relative, provision of emotional support and practical advice for themselves, education about medication, and information about how to motivate their relative to improve.

Furthermore, families are frequently confused and frustrated by the mental health system. They are confused about whom to contact in the bureaucracy, unclear about the programs and services for which their relative is eligible, and unable to adequately evaluate whether their relative benefits from treatment (9). Family members who are informed about the illness, the mental health system, and treatments for the illness are in a better position to communicate with providers and to know where to turn for assistance. Providers have limited time available to address the needs of families, but they are usually responsive to family-initiated requests. Family contacts with providers are generally confined to brief informal conversations or telephone calls (7). Clinicians frequently lack a full awareness of families' need for information. Consequently, many families who fail to express their needs effectively find them unmet.

The development of self-help support groups for families of adults with severe mental illness was partly motivated by discontent among family members with the unresponsiveness of mental health providers to their needs (10). Their subsequent expansion is testimony to the success of these groups. As these groups have focused their efforts more on advocacy, both families and providers have recently developed family education programs (11). The programs are highly structured and carefully planned approaches to meeting the growing and changing needs for information about severe mental illnesses and the services and resources to treat them (11).

Limited research has examined the general effectiveness of these interventions (11) and their specific effectiveness in increasing family members' utilization of and satisfaction with community resources. Findings in this area have been inconsistent. Posner and colleagues (12) found that compared with a control group, participants in an eight-week family education program had improved satisfaction with mental health services at termination but not at six-month follow-up. After families of patients being released from a state psychiatric hospital participated in a one-time educational workshop, Reilly and his colleagues (13) did not find any change in the degree of their involvement with their ill relative's treatment. But Smith and Birchwood (14) found a trend for families to be more optimistic about their role in treatment after participating in four weekly group sessions or receiving four weekly informational booklets sent through the mail. Families who participated in the Journey of Hope, a national educational program developed by a family member, reported increased awareness of mental health resources (15).

Given the inconsistency of the findings and the lack of research evaluating an individualized approach, we conducted the study reported here. The study tested the hypothesis that families of adults with severe mental illness who participate in either a group family education workshop or individual family consultation will seek more assistance from community resources than those in a control group who are on a waiting list. Community resources are defined as psychiatric treatment providers, community mental health agencies, self-help groups, lawyers, and others who offer support and assistance to family members with a mentally ill relative. Furthermore, the study examined the hypothesis that those who participate in family education interventions will be more satisfied with the resource contacts they do have than those in the control group.

Methods

This research is part of a larger study that assessed the effectiveness of two brief family education interventions—individual family consultation and a group workshop—for family members of adults with severe mental illness (16,17). Previous analysis found that at termination of the intervention the individual family consultation improved family members' self-efficacy, while the group workshop improved self-efficacy only for family members who had not previously been involved in family support and advocacy groups (16). Although these gains were maintained at six-month follow-up, no significant differences were found between groups at that point due to gradual maturation in the control group (17).

Recruitment

Family members were recruited from a 50-mile radius around a large East Coast city to participate in a randomized clinical trial of family education services. Family members were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: individual family consultation, group family education, and a control group on a nine-month waiting list. The family interventions did not include the ill relatives.

Recruitment was done through a network of support groups, hospital social service departments, and informational programs in area hospitals for family members of psychiatric patients. In addition, an advocate well known to families was employed to organize a public relations effort that included presentations, radio talk show appearances, and newspaper advertising. The family life columnist of the primary regional daily newspaper featured the project in her column, and a newspaper focused on the African-American community also ran a feature about the project. This recruitment strategy may have attracted a select sample of families who were not receiving adequate assistance from their network of resources.

Criteria

Families who were eligible to participate in the study were required to meet several criteria. The family member, or subject, was a parent, child, spouse, or other relative who had major responsibility for the ill relative. Major responsibility was defined as living with the family member, being a contact person for emergencies at rehabilitation residences or agencies, or engaging in frequent monitoring and support of the ill relative in independent living situations. The family member had to have in-person or phone contact with the ill relative an average of at least once a week, both had to live within a 50-mile radius of the metropolitan area, and both had to be at least 18 years old.

In addition, the ill relative was required to have a diagnosis of a major mental illness as determined by DSM-III-R—either schizophrenia (code 295) or a major affective disorder (code 296). The diagnosis had to have been made at least six months before the family member's entry into the study.

Every interested family member who met these criteria was asked to participate in the study. If more than one member of the same family was interested, the subject was selected by the toss of a coin.

Interviews and measures

Family members were interviewed by trained research workers independent of those providing the services under study. At the baseline interview, research workers described the study to family members individually, most often in families' homes. Research workers explained the purpose of study, answered questions, and acquired signed consent agreements to participate. Interviews were conducted again about three months later, after the interventions were completed. A follow-up interview was completed six months after the intervention phase, or nine months after baseline.

The interviews included questions about sociodemographic characteristics, such as employment, education, and income. Also included were questions about the history of the relative's mental illness and the subject's personal history with the ill relative and measures of burden, social support, coping, stress, grief, and self-efficacy. These measures are described in more detail elsewhere (16).

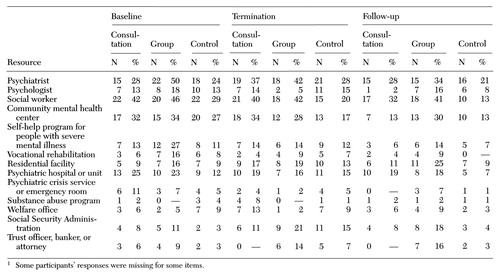

The interviews included sections about the extent of contact with mental health professionals, providers, and community resources. Family members were asked to report whether or not they had contact in the previous month with different service resources, listed in Table 1, which may have a role in care for their mentally ill relative. The extent of contact was operationalized as the sum of the assessments of those contacts and scored as 1, never; 2, rarely; 3, sometimes; 4, frequently, and 5, always. The higher the numbers, the greater the extent of contact. In Table 1 the values represent the number who responded rarely, sometimes, frequently, and always. These data were collected in interviews at all three time points.

Sample

A total of 244 family members who met study criteria were identified, of whom 225 consented to participate. Those who refused differed from those who consented in that they were more likely to be children of a mentally ill parent (χ2=52.04, df=1, p<.05).

The sample of 225 family members represented families with varied levels of involvement with support groups. A total of 114 of the family members (51 percent) had never participated in a family support group, and 130 (58 percent) had never been a member of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, a major advocacy group organized by family members.

Most of the family members in the study were female (198 subjects, or 88 percent) and white (189 subjects, or 84 percent), with a mean±SD age of 55.7±12.5 years. A majority of the family members had some college education (122 subjects, or 54 percent), and the sample's mean income was $36,600±$26,100 a year. The education and income of these families represent middle-class social-economic status.

Most participants were the parents of an adult child with mental illness (172 subjects, or 76 percent). Twenty-five participants (11 percent) were siblings, ten (4 percent) were spouses, and 13 (6 percent) were adult children of an ill parent. Five subjects (2 percent) had other relationships, such as in-laws or longtime companions.

A total of 134 ill relatives (64 percent) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The median number of lifetime psychiatric hospitalizations of the ill relatives was between three and five; 34 percent had more than five lifetime psychiatric hospitalizations. Their mean age was 35.8±10.9 years. The mean length of time since the initial diagnosis of their illness was 12.7±8.7 years.

Randomization and attrition

Randomization was accomplished through the use of a random numbers table. As each subject's randomly assigned numerical identifier was found in the table, that subject's name was entered into the next available slot in a chart that was divided by the three conditions and that provided a larger number of slots for the control condition. Of the 225 subjects at baseline, 66 were assigned to individual consultation, 67 to the group family workshop, and 92 to the waiting list.

More were assigned to the control group because greater attrition was expected from this group. Control subjects were paid $10 for the interviews and were provided either of the family education interventions, or both interventions, free of charge after nine months, provided they availed themselves of the group workshop before the individual consultation to prevent contamination of the groups.

Forty-two family members had dropped out of the study by the end of the intervention phase. Ten family members dropped out of the consultation, 20 dropped out of the group workshop, and 12 dropped off the waiting list. More family members dropped out of the group workshop condition (χ2=7.97, df=2, p<.05). Data for five family members in the group workshop were excluded from the analysis because they did not meet the attendance requirement of at least seven group sessions.

Dropout subjects were compared with those who remained in the study at the end of the intervention phase by gender, ethnicity, the diagnosis of the ill relative, relation to the ill relative (parent or nonparent), living arrangement (living with the ill relative or not), income, education, number of years the relative had been ill, and the baseline assessment scales of the outcome measures. No differences were found on any of these variables between family members who dropped out and those who remained in the study at three months. Because 19 tests of statistical significance were used for this comparison, a Bonferroni correction was used (.05/19=.0026).

Twelve subjects dropped out of the study between the end of the intervention phase and the follow-up interviews. Three dropped from the consultation condition, four from the group condition, and five from the waiting-list control condition. No differences were found by condition in the number of dropouts after service termination.

The remaining 171 subjects were compared by condition on the 19 sociodemographic, clinical history, and baseline assessment characteristics. No differences were found on sociodemographic, clinical, or baseline assessment variables by condition among the family members remaining in the three conditions at the nine-month follow-up. One participant in the group condition was contacted for a final follow-up interview even though the participant was not available for the three-month interview. Therefore, for some analyses of outcome at follow-up, the total sample is 172.

The interventions

Both interventions were administered by the Training and Education Center Network, a collaborative initiative of family members and mental health professionals experienced in providing family education to individuals with a mentally ill relative. The center hired, oriented, and supervised experienced specialists who provided both the individualized consultation and the group workshop. No specialist provided both group and individual consultation services. Subjects in both interventions were provided with the same instructional materials, but how these materials were used differed according to the model of family education employed.

Brief individual family consultation.

The individual consultation consisted of educational technical assistance provided to the family as a unit or to an individual family member (18,19,20,21). The consultants were mental illness specialists with expertise in teaching family members about mental illness; they also had skills in assessment, mediation, and problem management and knowledge of available resources. Staff less experienced in this intervention received a three-hour orientation in this model of family consultation, followed by ongoing supervision of cases by more experienced specialists.

A minimum of six hours of consultation was provided to each family, which included a two-hour initial assessment, at least two more hours of face-to-face contact, and at least two additional hours of face-to-face or telephone contact. A maximum of 15 hours was maintained to ensure comparability of the intervention across all subjects in this condition and to be comparable in duration with the group intervention. Families determined the specific focus of their work with the consultant and had access to the service as needed over the three months that the consultation service was available to them.

The consultation was conceptualized as having three phases: feeling and connecting, focusing, and finding. In the feeling and connecting phase, the consultant provided empathy and support to family members and acknowledged the strength of the family as the consultant took a brief history of the relative's illness. Issues of guilt and blame were addressed. The consultant assessed educational and skill needs with the family. In the focusing phase, an agenda was developed for the family's educational work. Problems were clarified or redefined. A priority list of objectives to be met was established.

The final phase focused on developing strategies to meet objectives. The consultant assisted the family or the family member in the process of developing new skills and evaluating their use in relating to the ill relative. Consultants often informed family members about community resources appropriate to their needs. Consultants occasionally accompanied family members to meetings at other agencies to assist them in gaining access to appropriate services for the ill relative.

Group family workshop.

Each family education workshop had as cofacilitators a mental illness specialist and a family member trained as a peer consultant. Groups usually consisted of six to 12 individuals and included some family members not participating in this study.

Group facilitators were selected based on their expertise in mental illness and professional experience in working with families and groups. Peer consultants enhanced the workshops with examples from their own experience and were expected to challenge the specialists or group participants if they disagreed with what was being presented or said. Weekly two-hour sessions were scheduled over a ten-week period. Some groups took longer due to rescheduling after severe winter weather, but all groups completed the ten sessions planned.

The objectives of the groups were to educate families about severe mental illness and its treatment, to help families realize that others in their situation have similar feelings and experiences, and to provide guidelines for dealing more effectively with their ill relative, other family members, and the mental health system. Thirty minutes of each two-hour weekly session were devoted to new information about mental illness and its treatment, and 90 minutes were devoted to the development of coping skills. Homework was usually assigned at the end of each session to help participants apply the material to interactions with their ill relative.

The mental illness specialists and peer consultants were experienced in conducting the workshop, using a 132-page teaching manual as a primary resource for facilitating the groups. Training consisted of nine hours of classroom education in attitudes and skills for effective group facilitation and observation of at least two group sessions. Ongoing technical assistance and support was available to group facilitators from the training center staff.

Analysis

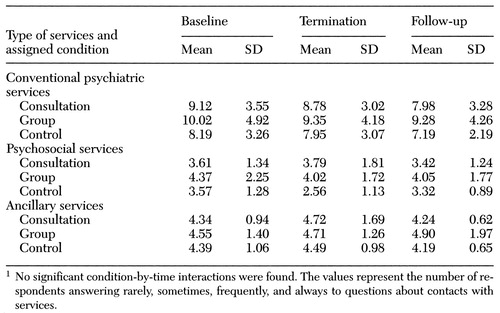

Repeated-measures analysis of variance was used to test for an effect of the interventions on family contact with mental health professionals. Three dependent variables were created by summing the ratings of extent of contact (from 1, never, to 5, always) with the specified resources: conventional psychiatric services, including contact with a psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, community mental health center, psychiatric inpatient unit, and crisis or emergency services; psychosocial services, including contact with self-help groups, vocational rehabilitation, and residential services; and ancillary services, including contact with substance abuse services, public welfare agencies, the Social Security Administration, or trust officers, bankers, and attorneys.

These three variables were analyzed by a two-factor repeated-measures design. One factor was condition: individual consultation, the group workshop, or the waiting list. The second factor was the three measurement points—baseline, three months, and nine months. An experimental effect for the conditions would be detected in a statistically significant result for the interaction of condition and measurement points.

Results

The outcome measures are reviewed by condition and interview point in Table 2. None of the repeated-measures analyses of variance showed statistically significant differences over time by condition in the extent of contact with any of the three types of mental health services. The analyses contained sufficient statistical power to detect a medium effect. Therefore, a clinically meaningful effect could have been detected if it were present.

Discussion

The hypothesis examined in this study—that family education would increase family members' contacts with community resources—was not supported. Neither educational intervention produced any change in behaviors of families seeking advice and assistance on behalf of their ill relative from conventional psychiatric services, from psychosocial rehabilitative services, or ancillary services. It may be worthwhile to modify the interventions. Increasing family contacts with community resources on behalf of the ill relative may enhance the impact of the intervention on both the ill relative and the family.

The group workshop uses a general approach to inform families of the illness, treatments, and resources. However, it has no specific focus on helping families devise strategies to obtain what they want for their ill relative from the mental health and ancillary service systems. Although gaining access to services is an underlying theme of the educational workshop, no session directly focuses on this topic.

In the individual consultation intervention, families develop a set of priorities on which to work with the consultant. Few families in this study prioritized access to services or ways to deal with difficult providers, because they chose other issues. Generally, those who received individual consultation had little opportunity to learn about how to work with community resources.

A growing core of providers, family members, and consumers agree that collaboration between these groups is among the most effective means to achieve the goals of treatment. Formalized training for family members in ways to collaborate with providers should be more a more fully integrated component of educational interventions.

Adding curriculum to family education programs about collaboration with providers is just one alternative among several. For example, families and providers can be trained together in special workshops geared toward mutual solutions to overcoming barriers to family-provider collaboration. The Training and Education Center Network has done a pilot study of this approach and has received positive feedback from both groups of participants (22).

Although families who participate in individual consultation may not express the goal of gaining greater access to providers and being more effectively included in treatment, such steps are easily incorporated as strategies toward other goals. For example, a father may express the need to know how to encourage his daughter's compliance with medication. In addition to role playing interaction with the daughter, the consultant may also role play interactions with the prescribing physician so that the daughter's concerns about her medication are more effectively communicated. These efforts may result in a more agreeable medication regimen for all concerned.

Recent research on the involvement of professionals with family members indicates that professionals' attitudes toward families may not be as important in explaining involvement with families as professionals' discipline and job role and the characteristics of their work settings, such as whether they work a day or evening shift or in community agencies or hospitals (23). Therefore, family sessions on access to resources should review strategies on the best ways to gain access and input to service systems and to identify different types of providers who are most likely to include families in planning and implementing various types of services.

With a broader understanding of how professionals interact in the mental health system, families are better prepared to seek access to and assistance from the most appropriate sources. They may also develop ideas about how to advocate for change on behalf of their ill relative. Family members' involvement could encourage professionals to collaborate more closely with them and their ill relative. Thus services may become more responsive to families' and consumers' needs.

One limitation of the study was that a number of participants dropped out. Although they did not differ on available measures from those who remained in the study, it is not known whether those who dropped out had more of their needs met through community resources.

Conclusions

As managed care imposes constraints focused on cost saving and increased effectiveness, service systems could benefit from including family education among their standard practices for the families of persons with severe mental illness. Family education could potentially help family members gain access to services that are linked to positive outcomes. However, the results of this study indicate that family education, as it is currently conceptualized, does not provide sufficient help.

To improve the impact of these interventions on outcomes for ill relatives, family educators should incorporate more information and skill building on ways to gain access to services. Family education interventions emphasizing involvement of family members in treatment may produce more informed collaborators for professionals within the ill relative's natural support network, thus extending the number of individuals implementing the treatment plan. Emphasis on family involvement in treatment may also strengthen the impact of the family education intervention itself. Few effects of family education have been found for the ill relative, because such interventions are typically brief and are only indirectly related to outcomes. However, an emphasis on family involvement in treatment strengthens the conceptual link between the family educational intervention and the outcome for the ill relative.

Acknowledgment

This research was funded by grant HD5SM49208 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Dr. Solomon is professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Pennsylvania, 3701 Locust Walk, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Draine is research assistant professor at the Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research of the department of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania. Ms. Mannion is technical director and Ms. Meisel is executive director of the Training and Education Center Network of the Mental Health Association of Southeastern Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

|

Table 1. Involvement with resources in the past month of 225 family members with a mentally ill relative assigned to individual consultation, a group intervention, or a waiting list (control group), at baseline, at the termination of the intervention, and at follow-up six months after termination1

|

Table 2. Extent of contact in the past month with three types of services of 225 family members with a mentally ill relative assigned to individual consultation, a group intervention, or a waiting list (control group), at baseline, at the termination of the intervention, and at follow-up six months after termination1

1. Grella CE, Grusky O: Families of the seriously mentally ill and their satisfaction with services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:831-835, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Solomon P: Families' views of service delivery: an empirical assessment, in Helping Families Cope With Mental Illness. Edited by Lefley HP, Wasow M. Chur, Switzerland, Harwood, 1994Google Scholar

3. Solomon P, Draine J: Subjective burden among family members of mentally ill adults: relation to stress, coping, and adaptation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 65:419-427, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hatfield AB, Gearon JS, Coursey RD: Family members' ratings of the use and value of mental health services: results of a national NAMI survey. Psychiatric Services 47:825-831, 1996Link, Google Scholar

5. Hatfield AB: What families want of family therapists, in Family Therapy in Schizophrenia. Edited by McFarlane WR. New York, Guilford, 1983Google Scholar

6. Holden DF, Lewine RRJ: How families evaluate mental health professionals, resources, and effects of illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 8:626-633, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Bernheim KF, Switalski T: Mental health staff and patient's relatives: how they view each other. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:63-68, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Solomon P, Marcenko M: Families of adults with severe mental illness: their satisfaction with inpatient and outpatient treatment. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16:121-134, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Mueser KT, Gingerich S: Coping With Schizophrenia. Oakland, Calif, New Harbinger, 1994Google Scholar

10. Hatfield AB: Help-seeking behavior in families of schizophrenics. American Journal of Community Psychology 7:563-569, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Solomon P: Moving from psychoeducation to family education for families of adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 47:1364-1370, 1996Link, Google Scholar

12. Posner C, Wilson K, Kral M, et al: Family psychoeducational support groups in schizophrenia. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 62:206-208, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Reilly J, Rohbaugh M, Lachner J: A controlled evaluation of psychoeducation workshops for relatives of state hospital patients. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 14:429-432, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Smith J, Birchwood M: Specific and non-specific educational intervention with families living with a schizophrenic relative. British Journal of Psychiatry 150:645-652, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Pickett SA, Cook JA, Laris A: The Journey of Hope: Final Evaluation Report. Chicago, University of Illinois at Chicago, National Research and Training Center on Psychiatric Disability, 1997Google Scholar

16. Solomon P, Draine J, Mannion E, et al: Impact of brief family psychoeducation on self-efficacy. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:41-50, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Solomon P, Draine J, Mannion E, et al: Effectiveness of two models of brief family education: retaining gains by family members of adults with serious mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:177-186, 1987Google Scholar

18. Bernheim K: Supportive family counseling. Schizophrenia Bulletin 8:634-640, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Bernheim K: The role of family consultation. American Psychologist 44:561-564, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Bernheim K, Lehman A: Working With Families of the Mentally Ill. New York, Norton, 1985Google Scholar

21. Kanter J: Consulting with families of the chronic mentally ill. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 27:21-32, 1985Google Scholar

22. Mannion E, Meisel M: Reducing culture clash in family-provider relationships: a bilateral perspective. New Directions for Mental Health Services, in pressGoogle Scholar

23. Wright ER: The impact of organizational factors on mental health professionals' involvement with families. Psychiatric Services 48:921-927, 1997Link, Google Scholar