Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Other Predictors of Health Care Consumption by Vietnam Veterans

Abstract

A total of 641 randomly selected Australian veterans of the Vietnam War were interviewed about their use of health care in the previous two weeks to determine what factors contributed to health care consumption. Seventy-three variables were examined by univariate linear regression and then grouped into seven categories relating to age, physical and mental health, predisposition to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), deployment and repatriation experiences, and membership in veterans groups. PTSD was associated with an additional cost of $79 in health care for the two-week period. Each physical diagnosis was associated with an additional $28. Alcohol consumption was not related to health care costs. Other important variables contributing to costs were depression, educational status, the quality of the repatriation experience, and social support.

In support of the U.S. intervention in South Vietnam, Australia sent 50,000 combat troops to the war. Half were conscripts. It has been demonstrated in many previous studies internationally that war service takes a heavy toll on the physical and mental health of many participants (1). One of the more common disorders among veterans is posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (2).

For war veterans, variables related to health care consumption include age, exposure to combat (in terms of both recentness and intensity), the presence of injuries or other physical illnesses, subjects' attitudes toward their Vietnam service, and the availability of social supports (3).

Because most health care is focused on treatment of specific diagnosed disorders, our starting hypothesis was that the number of diagnoses veterans reported would relate closely to their health care consumption. The study reported here was designed to examine this relationship and also the relative effects of mental health and other factors on health care consumption.

Methods

Between January 1990 and April 1992, we interviewed 641 Vietnam veterans from a random sample of 1,000 veterans from the nominal roll of Australian soldiers who had been exposed to combat in Vietnam. The 641 veterans represented 87 percent of the 737 living veterans who could be located out of the group of 1,000 veterans (4).

Questionnaires about health and psychological state were administered to each subject. These were supplemented with psychological data from army personnel records and enlistment records held by the Defense Force. Health care consumption was calculated from veterans' self-reports of seven types of health services used in the two weeks before the interview weighted by the fee scheduled for payment by the federal government or the average cost of the service in 1991-1992. Costs are reported in U.S. dollars on the basis of the 1991-1992 exchange rate. We used the two-week period before the interview because it has been determined to be a robust recall period for self-report (5).

Outliers, or high users of services, were retained in the calculations to ensure that this small but important group would contribute to the aggregate cost estimates. Even though a short reporting window was used, only 14.5 percent of subjects were nonconsumers of any health care during the period because information about use of all health care, including medication (prescribed and self-obtained), was elicited.

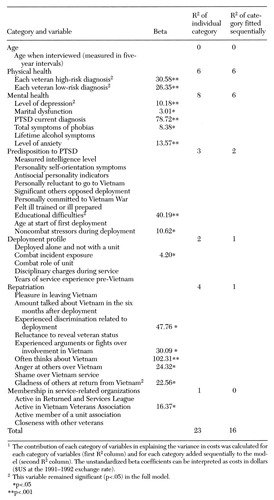

We examined 73 predictor variables (6) that were relevant to the constructs to be examined. We omitted 36 from the final regression model because they were collinear with the variables that were included. The remaining 37 variables were grouped into the seven categories listed in Table 1. A univariate linear regression approach was taken in examining all variables individually because the unstandardized beta coefficients generated by these analyses can be interpreted as the dollar costs associated with the variable concerned.

The seven categories of factors were then examined in a linear regression model to assess the amount that each category contributed to the variance in costs. The categories were then fitted to the model hierarchically, and variance was observed to identify how distinct from each other the categories were in their effects.

Results

Table 1 lists the 37 factors examined in the full regression model for their influence on health care consumption. For the physical health factors, we found that the presence of each diagnosis commonly found in veterans (high-risk diagnoses) added $31 to the fortnightly health care consumption cost per veteran (p<.001). Each low-risk diagnosis added $26 (p<.001).

Because the sample was concentrated in a narrow age range, the age variable was not significantly associated with reported health care consumption.

All the mental health variables except symptoms of alcohol dependence and abuse related individually to health care consumption. When the effects of other factors were not controlled, the presence of a clinical diagnosis of PTSD predicted an additional $79 of health care consumption per fortnight (p<.001). However, depression was the only mental health variable that continued to be significantly associated with health care consumption in the full model.

Of the variables predisposing a veteran to PTSD, educational difficulties were strongly associated with health care use, even after all other variables were controlled. Stressors not related to combat during deployment, such as the death of a parent, were also related to health care use in the univariate analysis, as were the attitudes of significant others toward the veteran's deployment.

Only one of the deployment variables was significantly related to health care consumption—the intensity of the veteran's combat exposure (beta=$4.20, p<.05).

Among the repatriation variables, the one that stands out is whether veterans thought frequently of their Vietnam service (beta=$102, p<.001). Veterans' belief that they had been discriminated against because of their Vietnam service added $48 to the fortnightly service cost (p<.05). Having been involved in fights because of their veteran status added $30 (p< .05). Continuing anger about Vietnam added $24 (p<.05), and lack of welcome from significant others on return from Vietnam added $23 (p<.05).

Analyses of the next category of factors, membership in service-related groups, indicated that only membership in the Vietnam Veterans Association was associated with higher use of health care (beta=$16, p<.05).

The first R2 column in Table 1 shows the variance accounted for by each category of variables when the category is considered individually. The other R2 column shows the increase in variance when each category of factors is added sequentially to the model.

When examined individually, each category was found to explain at least 1 percent of the variance. Mental health variables explained the largest amount of variance (8 percent). If each of the categories is considered independently, we might look for a total effect of up to 23 percent of variance explained. In the full model, the overall R2 of 16 percent indicates a significant overlap between the categories of factors.

Discussion and conclusions

These results demonstrate that health care consumption is related not only to the number of diagnoses that a person reports but also to his or her reported mental health status and social supports. Although lifetime alcohol abuse problems were detected in 74 percent of subjects, they were not related to reported health care consumption, contrary to what we expected based on the results of earlier clinical studies (7).

It appears that a proportion of the additional health care used by veterans with PTSD was at least nominally related to physical comorbidity. In previous studies, a strong relationship between PTSD and other symptom clusters has been reported (8,9). Consistent with these findings, we observed overlap between the effects of physical and mental health variables.

It might be suggested that the relationship between educational difficulties and higher health care consumption is mediated by intelligence. However, no relationship between health care consumption and lower intelligence scores was observed when the analysis controlled for physical health. Therefore, the observed effects of educational disadvantage may have been due to acquired information and learned skills rather than intellectual ability.

The strong association between health care consumption and the lack of welcome on homecoming from Vietnam, which added $11,732 to per-person health care costs in the 20 years since deployment, remained after the analysis controlled for mental health. So many years since the war, the strong relationship between higher health care consumption and veterans' perception of a lack of support from others emphasizes the importance of positive affirmation of veterans' service when they return.

This study demonstrates that the mental and physical health problems of Vietnam veterans and other peacekeeping veterans continue to warrant particular attention in their health care planning. The clear link between PTSD and a high level of health care consumption indicates the importance of prevention and effective management of this disorder (10). We also urge defense and repatriation authorities to give particular attention to social support factors relating to defense deployments. Further investment in prevention programs and deployment support appears to have significant potential for health outcomes and cost savings.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a case mix education and study grant from the Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services. Data collection was partly supported by grants from the public health research and development committee of the National Health and Medical Research Council, the Australian Vietnam War Veterans Trust Ltd., the Department of Veterans' Affairs, the Westmead Research Institute, and the Australian War Memorial. The authors are grateful for assistance from the Department of Defense (Army) and, in particular, the department's first psychological research unit in Canberra, which provided facilities and support for data extraction and analysis.

Mr. Marshall and Dr. Jorm are affiliated with the Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Centre of the National Health and Medical Research Council at Australian National University, Canberra, New South Wales, Australian Capital Territory 0200, Australia (e-mail, [email protected]). Mr. Marshall is also with the first psychological research unit of the Australian Department of Defense in Canberra. Dr. Grayson is with the Centre for Education and Research on Ageing at the University of Sydney. Dr. O'Toole is with the department of public health and community medicine of the University of Sydney and the department of marketing of the University of Western Sydney.

|

Table 1. Regression analyses of seven categories of variables examined for associations with health care consumption by 641 Australian combat veterans of the Vietnam War1

1. Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, et al: Trauma and the Vietnam Generation: Report of Findings From the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study, vol 1. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1990Google Scholar

2. O'Toole B, Marshall RP, Grayson DA, et al: War and mental health, in Men and Mental Health. Edited by Jorm AF. Canberra, National Health and Medical Research Council, 1995Google Scholar

3. Blaume CS, Liang J, Liu X: The relationship of chronic disease and health status to the health services utilization of older Americans. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 42:1087-1093, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. O'Toole BI, Marshall RP, Grayson DA, et al: The Australian Vietnam veterans health study: I. study design and response bias. International Journal of Epidemiology 25:307-318, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. 1989-90 National Health Survey: User's Guide. Catalogue no 4363.0. Canberra, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1991Google Scholar

6. Marshall RP, Grayson DA, Jorm AF, et al: Help seeking in Vietnam veterans: post-traumatic stress disorder and other predictors. Australian Journal of Public Health 21:211-213, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Kent S, Fogarty M, Yellowlees P: Heavy utilization of inpatient and outpatient services in a public mental health service. Psychiatric Services 46:1254-1257, 1995Link, Google Scholar

8. Van der Kolk BA, McFarlane AC, Weisaeth L: Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Overwhelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society. New York, Guilford, 1996Google Scholar

9. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:1048-1060, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Dobson M, Marshall RP: Surviving the war zone experience: preventing psychiatric casualties. Military Medicine 162:283-287, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar