Mental Health Staffing in Managed Care Organizations: A Case Study

Abstract

This paper examines temporal changes in staffing ratios and configuration of mental health providers per 100,000 members within two full- service staff-model health maintenance organizations (HMOs). Overall workforce reductions in all classes of mental health professionals occurred in the two HMOs from 1992 to 1995. Staffing ratios decreased in both HMOs for psychiatrists and psychologists. In one HMO, the ratio of clinical social workers also decreased over this period. Provider ratios from 1995 are benchmarked against state ratios per 100,000 population. Workforce mix for the two HMOs is contrasted with a single-year average for a large managed behavioral health (carve-out) organization. The authors discuss potential implications of the findings for training of several categories of mental health professionals.

Researchers who have studied the health care workforce have recognized that group- and staff-model health maintenance organizations (HMOs) may provide valuable clues about the future size and composition of the U.S. health care workforce (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11). Most studies of clinical staffing have been limited to cross-sectional analyses and have not focused on the range of mental health professionals used to staff integrated HMOs. The bulk of the literature has examined the impact of managed care on physicians (5,6,10), ignoring the impact of the managed care market on other professionals. Our data and analysis help fill this gap.

We begin by describing the current trends in mental health managed care. Then we present data on mental health staffing and mix of providers from a case study of two large staff- or group-model HMOs located in different Western states for the years 1992 to 1995. These staffing figures are then compared with those from a single behavioral health organization and with the ratio of providers per 100,000 population in the respective states where the HMOs are located. Finally the changes in ratios and distribution patterns of mental health professionals in the two HMOs are discussed.

Background

Integrated managed care organizations attempt to avoid fragmentation in the delivery of patient care, reduce utilization, and limit the organization's financial risk by the use of gatekeepers. This practice limits the number of contacts between specialty providers and patients (12,13). The use of gatekeepers, however, raises the concern of mental health providers that patients' access to appropriate mental health services may be curtailed (14). In addition, whether primary care physicians or mental health professionals should function as gatekeepers for mental health care has been of concern.

The rise in contracting between managed care organizations, managed behavioral health care plans, and providers has been largely responsible for the recent changes in the organization of mental health care delivery. In these carve-out arrangements, the delivery or administration of mental health services is not integrated into the managed care organization's main benefit plan but is instead contracted separately to a managed behavioral health firm. Managed behavioral health firms may accept a prearranged payment to perform only management functions, or they may accept financial risks for providing all mental health services as part of the contract through capitation arrangements. In a 1997 national survey of behavioral health organizations and HMOs, Oss and associates (15) found that 110.2 million members were enrolled in non-risk-bearing organizations and 58.4 million members were enrolled in risk-bearing organizations, which included risk-bearing behavioral health networks and mental health services within integrated HMOs.

All models have in common the use of utilization review and gatekeepers to contain cost and improve efficiency. Under managed care arrangements, control over services is being shifted from independent mental health providers to the managed care organizations that organize and deliver the care (16,17,18).

As more providers and managed behavioral health plans assume the risk of capitation, organizations responsible for care delivery will have a strong financial incentive to utilize the mix of professional staff that is most cost-effective. Purchaser-driven price competition in the managed care industry has increased dramatically since 1990 and has served to motivate mature HMOs to implement clinical staffing innovations that reduce costs (19).

Expected staffing changes in organizations that provide mental health services include the use of nonphysician mental health providers who act as economic substitutes or complements for physicians, including psychiatrists (20). Economic substitution, in which one worker may perform certain duties of another worker, also occurs among mental health specialists. For example, clinical social workers may be substituted for doctoral-level psychologists in providing such services as counseling. The use of the term "substitution" is not meant to imply these providers are exactly alike. Moreover, researchers have pointed out concerns about the quality and appropriateness of care when lower-cost clinicians or primary care physicians are substituted for better-trained specialists (21,22). In contrast to substitution, complementary roles are roles one provider performs that are not commonly performed by another provider. For example, psychiatrists may prescribe medication and clinical social workers may be expert at case management; thus their roles complement each other.

Before the 1990s, physicians provided most care in managed care organizations. In recent years, managed care organizations have increased their use of nonphysician mental health providers. The appropriate degree of economic substitution of one type of provider for another remains controversial. However, the financial savings realized by using lower-paid nonphysician health professionals to deliver mental health services could also serve as an incentive for the development of a more collaborative medical practice. In such a practice each mental health provider would assume a special role in the delivery of care using his or her unique skills to meet the patient's mental health care needs (23). The workforce dynamics we report in this paper suggest that notable changes are under way in the staffing of managed care organizations as they develop new configurations for the delivery of mental health services.

Case study

To examine the staffing of mental health professionals in integrated managed care systems, we collaborated with the Institute of Medicine to collect staffing data for the period from 1992 to 1995 from two large not- for-profit, well-established HMOs in two Western states. We studied examples of group- or staff-model organization because this model has been used as a prototype for efficient workforce staffing in the health care system (2,10,24).

The two HMOs are located in separate metropolitan areas, each with a population of more than 1 million. Each HMO is located in a metropolitan market where price competition among health plans has intensified in recent years. Each is a full-service HMO that is capitated for all care, including mental health care, and thus fully at risk for such care.

The first (HMO A) is a group-model HMO that contracts with one large multispecialty medical group for most physician services, including psychiatry and behavioral health services. The second (HMO B) is a staff-model HMO that directly employs most of its physicians. Both organizations can be described as closed-panel HMOs in that most of their medical staff treat HMO members exclusively. However, each organization relies to some extent on outside physicians for emergency treatment and specialty services. Both HMOs are not-for-profit, mature organizations, each with more than 250,000 members. The two organizations are similar in the gender and age of their enrollees and in the percentage of enrollees in Medicare and Medicaid.

Because mental health care is increasingly delivered by managed behavioral health organizations through carve-out arrangements (25), we also collected data on the mix of providers at one large behavioral health carve-out plan from the same area where HMO A is located. The plan provided data on the numbers of providers in each specialty. Data for only 1995 were available.

Data collection

Part of the data used in this analysis was collected in 1994 and 1995 by the Institute of Medicine to explore the future of primary care (26). Surveys that requested detailed data on clinical staffing and organizational features over a three-year period (1992 through 1994) were mailed to 12 geographically dispersed, nonrandomly selected HMOs, two of which provided comprehensive data about staffing for mental health services provision. With the permission of the Institute of Medicine, we directly contacted the two HMOs selected for this study. We obtained additional information to fill gaps in the data reported to the Institute of Medicine, collected data for a fourth year (1995), and interviewed key executives within each organization.

The HMO staffing figures presented here represent the average number of full-time-equivalent (FTE) clinical staff—those directly involved in patient care—for each calendar year. FTE figures were requested for psychiatrists and nonphysician mental health workers in the following categories: master's-level counselors, clinical social workers, doctoral-level psychologists, and clinical nurse specialists. We excluded physicians and other health professionals who perform primarily administrative roles or other non-patient-care roles (24). Part-time staff were reflected as partial FTE staff in the data analysis.

The gross number of providers reported for the carve-out plan located near HMO A reflects the fact that providers may have contracts with such organizations without providing full-time services or any services. Thus it is difficult to estimate from contract data the number of lives covered per provider. Therefore we compared the percentages of contracting providers in various professional categories affiliated with the carve-out plan with the percentages of providers in the same professional categories at HMO A and B. This strategy focused the comparison on overall staffing configurations rather than the absolute numbers of providers.

Results

Overall enrollment and staffing trends

HMO A experienced a 5 percent decline in overall membership from 1992 to 1995 that was accompanied by almost a 6 percent decline in the total number of patient care physicians. In contrast, HMO B showed a 10 percent growth in membership over the same period, but experienced an 8 percent decline in total number of patient care physicians. Thus, while the two HMOs differed in their enrollment changes, both experienced a decline in the number of patient care physicians. For both HMOs, analysis of the members' age and gender and of the percentage of Medicaid enrollees among members revealed little change over a four-year period (Ivey SL, Scheffler R, unpublished data, 1996).

Changes in staffing of mental health professionals

Comparisons between HMOs.

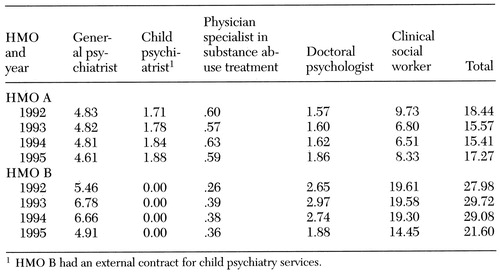

Table 1 shows the numbers of FTE mental health providers per 100,000 enrollees in HMO A and B. We examined changes between 1992 and 1995 for each of the following provider groups: psychiatrists, doctoral-level psychologists, and clinical social workers.

In 1995, the staff of HMO A included 4.6 FTE general psychiatrists and 1.9 FTE child psychiatrists, for a total of 6.5 FTE psychiatrists per 100,000 covered lives. This ratio was about half the 1995 national average ratio of 12.5 clinically active FTE general and child psychiatrists per 100,000 U.S. population (27). (This figure excluded residents, fellows, and physicians practicing outside the 50 states and the District of Columbia.) HMO A's ratio also was about half the 1996 ratio of psychiatrists per 100,000 population in the state where that HMO is located (28). Over the study period, the overall number of general psychiatrists in HMO A decreased by 9.5 percent, and the ratio of psychiatrists per 100,000 members decreased by 4.6 percent (from 4.8 per 100,000 in 1992 to 4.6 per 100,000 in 1995). The number of child psychiatrists increased by 4.4 percent during the study period, and the number of child psychiatrists per 100,000 members increased by 10 percent.

During this same period, HMO B also reduced its ratio of general psychiatrists, from 5.5 to 4.9 per 100,000 covered lives, a drop of about 10 percent. However, HMO B had a separate external contract for child psychiatry. Although the exact number of FTE child psychiatrists at HMO B was unknown, the overall percentage of all physicians with external contracts (external FTEs) was 15 percent. Using that percentage, we can interpolate a total of .75 FTE child psychiatrists per 100,000 members. For 1995, the ratio of general psychiatrists per 100,000 members of HMO B was similar to that of HMO A (4.9 and 4.6, respectively). In 1995, HMO B's ratio of psychiatrists per 100,000 members was about half the state's 1996 average number of psychiatrists per 100,000 population (28).

The ratio of doctoral-level psychologists for HMO A in 1995 was 1.9 per 100,000 covered lives, compared with the 1996 ratio of nearly 24 per 100,000 population for the state in which the HMO is located. Similarly, the ratio of doctoral-level psychologists for HMO B was 1.9 per 100,000 members in 1995. This ratio is nearly ten times lower than the 1996 average per 100,000 population for the state in which HMO B is located (28). Between 1992 and 1995, HMO B reduced the number of psychologists from 2.7 per 100,000 members to 1.9 per 100,000 members, the same ratio of psychologists at HMO A in 1995. However, HMO A had been increasing its use of psychologists between 1992 and 1995.

HMO A showed a small decline from 1992 to 1994 in the ratio of licensed clinical social workers per 100,000 covered lives, and a slight increase between 1994 and 1995. The ratio for 1995 was 8.3 per 100,000, less than one-quarter of the 1996 national average of 35.9 licensed clinical social workers per 100,000 population and roughly one-third of the 1996 ratio in the state where HMO A is located. HMO B used more licensed clinical social workers than HMO A—an average of 14.5 per 100,000 in HMO B in 1995. The ratio of licensed clinical social workers at HMO B fell about 26 percent between 1992 and 1995, constituting a large portion of overall staffing decreases. The 1995 ratio for HMO B was about 46 percent of the 1996 ratio for the state in which the HMO is located (27).

In summary, the two HMOs had much lower staffing ratios for all mental health workers than the provider ratios in the states where each is located. Changes in staffing ratios did not appear to be related to changes in the demographic characteristics of HMO enrollees over the study period (Scheffler R, Ivey SL, unpublished data, 1996).

Comparisons between HMOs and the mental health carve-out plan.

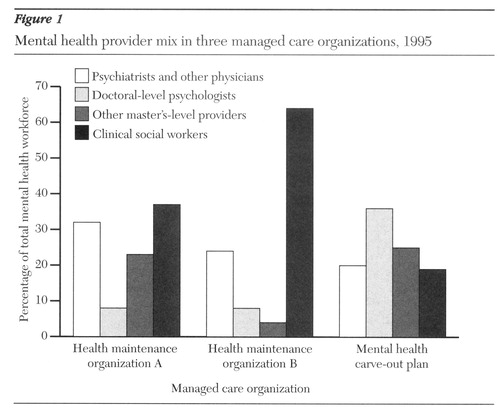

Data from 1995 for a specific geographic area from a large multistate mental health carve-out plan were obtained. For this analysis, we used data on a group of providers who had contracts with this plan and who practiced in a metropolitan area that covered roughly the same geographic area served by HMO A. We compared the percentages of various types of mental health clinicians in the workforce of HMO A, HMO B, and the carve-out plan. Figure 1 shows these data.

The physician mix included psychiatrists and any physicians who practice primarily in the area of mental health. For example, physicians specializing in treating substance use disorders were included. Primary care physicians who provide mental health care but who do not practice exclusively in the area of mental health were excluded from the analysis. In 1995, 32 percent of the specialty mental health workforce in HMO A were physicians, compared with 24 percent of the workforce in HMO B and 20 percent of the workforce in the carve-out plan.

Doctoral-level psychologists constituted 8 percent of all mental health clinicians in HMO A and B and 36 percent of the clinicians in the carve-out plan. Thirty-seven percent of HMO A's mental health clinicians were licensed clinical social workers, compared with 64 percent of HMO B's clinicians and 19 percent of the carve-out plan's clinicians. In HMO A, other master's-level workers, such as marriage and family therapists and clinical nurse specialists, constituted 23 percent of providers; only 4 percent of HMO B's workforce was in this category. HMO B reported a much lower ratio of clinical nurse specialists and psychiatric nurse practitioners than HMO A. However, HMO B appeared to use more licensed clinical social workers. In the carve-out plan, other master's-level health professionals constituted 25 percent of the workforce.

These differences may indicate that other master's-level workers were being substituted for either licensed clinical social workers or doctoral-level psychologists, as the percentage of physicians in the workforce seemed to be relatively similar across these organizations. However, the difference in health care workforce ratios may also result from disparities in the provision of services and acuity of patient-mix between organizations, in the financial structure of the organizations, or in the likelihood that certain providers are more willing to contract with managed care organizations.

Conclusions

Recent data from two HMOs and one mental health carve-out plan show the breadth of staffing configurations for mental health professionals operating within managed care settings. Data on trends from 1992 to 1995 in two group- or staff-model HMOs in Western states also demonstrate changes over time in the mental health workforce in integrated full-service HMO settings. The data show decreases in the number of psychiatrists as well as overall workforce reductions for other classes of mental health professionals in these two organizations in competitive markets.

The competitive climate of the managed care market may partially explain the observed changes in staffing ratios and the decline in the overall workforce. Markets with a high level of managed care penetration and increasing competition would seem to hold stronger economic incentives for economic substitution of certain workers for others. Furthermore, an increase in managed care penetration and the possibility that staffing ratios for certain mental health providers may be lower in staff-model HMOs than overall state or national ratios raise issues about the job market for recent mental health graduates. The growth in the number of new graduates of doctoral psychology programs (both Ph.D. and Psy.D. programs) and master's-level and doctoral programs in clinical social work far exceeds the number of recent U.S. medical graduates selecting psychiatry training (29,30).

The actual number of new doctoral-level psychology graduates totaled about 3,000 in 1996. This total included individuals trained in research psychology who will not enter clinical practice. The American Psychological Association estimated that 2,400 of these graduates trained in clinical specialties (30,31). In 1995 there were nearly 13,000 new graduate master's-level social workers and about 300 new graduate doctoral social workers. A smaller number of graduates are clinical social workers (personal communication, Council on Social Work Education, 1996).

The supply of graduates may reflect the needs of managed care organizations and behavioral health care plans and the reconfiguration of the market's demand for certain mental health professionals. Clearly graduates of all types may be entering markets with a shrinking demand for certain providers, at least in competitive markets in which the level of managed care penetration is high (20).

Data were not available for paraprofessionals nor for the level of direct provision of mental health services by primary care gatekeeper physicians. Nor were we able to obtain specific diagnostic code data that might illustrate a change in type or frequency of mental health services by provider type, though such changes have been occurring in the industry in general (32,33,34).

In light of this case study, some overarching questions come to mind: First, what staffing configuration will provide optimal efficiency and quality of mental health care, and does this configuration vary by organization type? How do these changes, seen in managed care settings at a local level, interrelate with reconfigurations in the national mental health workforce? Last, how could an increased focus on collaboration among provider types (including explicit training) improve the delivery and quality of services to patients and clients?

Evaluation, including outcomes measurement for newer models and teams of workers, is needed. Researchers within a practice setting could contribute to this effort. In addition, an important role for both psychiatrists and doctoral-level psychologists in hospital and managed care settings has become the supervision of master's-level mental health workers trained in such fields as psychology and marriage and family counseling (35). Further research in managed care settings may demonstrate that economic substitution of nonspecialist physicians contributes to workforce reductions among mental health specialists. Research on staffing in other types of managed care organizations, such as carve-out behavioral health care organizations, as well as on workforce needs in the public mental health sector is needed.

In addition, documentation of decreases in staffing in competitive markets suggests that the output of all types of postbaccalaureate providers warrants reexamination. Rising numbers of clinical nurse specialists certified in psychiatry and capable of prescribing in many states represent another scenario ripe for economic substitution, but also the possibility of nursing specialists' forging a complement to other provider types.

Unlike the predominance of restricted provider panels in managed care organizations in the late 1980s, it now appears that all types of mental health professionals are practicing in managed care settings (36). Directions for further research include continued monitoring of workforce reconfiguration in various types of managed care organizations and investigation of optimally efficient workforces that maintain patients' access to high-quality mental health care. With no one group of mental health professionals having a lock on service delivery, new, more collaborative models for care could evolve, reintegrating comprehensive mental health care into primary care settings.

Psychiatric Services Resource Center Releases Compendium on Families

A compendium of 13 articles on families and their involvement in mental health treatment has just been released by the Psychiatric Services Resource Center. All of the articles originally appeared inPsychiatric Services and Hospital and Commmunity Psychiatry.

Lisa B. Dixon, M.D., a Baltimore psychiatrist who is active in the family advocacy movement, wrote the introduction to the 72-page compendium, entitled Families&Mental Health Treatment.The articles focus on the needs and concerns of families of adults with severe and persistent mental illness, highlight the family and parenting needs of persons suffering from mental disorders and their children, and examine the costs to families associated with severe mental illness.

A copy of the compendium will be sent free to mental health facilities enrolled in the Psychiatric Services Resource Center. Staff in Resource Center facilities may order additional single copies (regularly priced at $13.95) for $8.95. For ordering information, call the Resource Center at 800-366-8455 or fax a request to 202-682-6189.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Center for Mental Health Services Research through grant P50 MH436 94-10 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Scheffler and by research training grant T32 MH18828-10 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Ivey. The authors thank Angela Ip, M.P.H., for her comments.

Dr. Scheffler is professor of health economics and public policy in the School of Public Health and the Goldman School of Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley. Dr. Ivey is a family and emergency physician and research specialist at the Center for Family and Community Health in the School of Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley, California 94506 (e-mail, [email protected]). Address correspondence to Dr. Ivey.

Figure 1. Mental health provider mix in three managed care organizations, 1995

|

Table 1. Number of full-time-equivalent mental health providers per 100,000 covered lives in two staff-model health maintenance organizations (HMOs), 1992-19951

1. Anderson G, Han C, Miller R, et al: A comparison of three methods for estimating the requirements for medical specialists: the case of otolaryngologists. Health Services Research 32:139-153, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

2. Goodman K, Fisher E, Bubolz T, et al: Benchmarking the US physician workforce: an alternative to needs-based or demand-based planning. JAMA 276:1811-1817, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Schroeder S: How can we tell whether there are too many or too few physicians? The case for benchmarking. JAMA 276:1841-1843, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Council on Graduate Medical Education (COGME): Managed Health Care: Implications for Physician Workforce and Medical Education. COGME's Sixth Report to Congress and the HHS Secretary. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1995Google Scholar

5. Cooper RA: Perspectives on the physician workforce to the year 2020. JAMA 274:1534-1543, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Dial TH, Palsbo SE, Bergsten C, et al: Clinical staffing in staff- and group-model HMOs. Health Affairs 14(2):168-180, 1995Google Scholar

7. Kronick R, Goodman D, Wennberg J, et al: The marketplace in health care reform: the demographic limitations of managed competition. New England Journal of Medicine 328:148-152, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Steinwachs D, Weiner J, Shapiro S, et al: Comparison of the requirements for primary care physicians in HMOs with projections made by the GMENAC. New England Journal of Medicine 314:217-222, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Weiner J, Steinwachs D, Williamson J: Nurse practitioner and physician assistant practices in three HMOs: implications for future US health manpower needs. American Journal of Public Health 76:507-511, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Weiner JP: Forecasting the effects of health reform on US physician workforce requirement: evidence from HMO staffing patterns. JAMA 272:222-230, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Wennberg JE, Goodman DC, Nease RF, et al: Finding equilibrium in US physician supply. Health Affairs 12(2):89-103, 1993Google Scholar

12. Shortell SM, Gillies RR, Anderson DA, et al: Remaking Health Care in America: Building Organized Delivery Systems. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1996Google Scholar

13. Sullivan S, Flynn T: Reinventing Health Care: The Revolution at Hand. Washington, DC, National Committee for Quality Health Care, 1992Google Scholar

14. DeGruy F: Mental Health Care in the Primary Care Setting, in Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era. Edited by Donaldson MS, Yordy KD, Lohr KN, et al. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1996Google Scholar

15. Oss M, Drissel A, Clary J: Managed Behavioral Health: Market Share in the United States, 1997-98. Gettysburg, Penn, Open Minds Publications, 1997Google Scholar

16. Robinson J, Casalino L: Vertical integration and organizational networks in health care. Health Affairs 15(1):7-22, 1996Google Scholar

17. Robinson J, Casalino L: The growth of medical groups paid through capitation under managed care in California. New England Journal of Medicine 333:1684-1687, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Shortell S, Hull K: The new organization of health care: the evolution of managed care and organized delivery systems, in Strategic Choices for a Changing American Health System. Edited by Altman S, Reinhardt U. Chicago, Health Administration Press, 1996Google Scholar

19. Miller RH, Luft HS: Estimating health expenditure growth under managed competition: science, simulations, and scenarios. JAMA 273:656-662, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Ivey SL, Scheffler R, Zazzali JL: Supply dynamics of the mental health workforce: implications for health policy. Milbank Quarterly 76:25-58, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Kirmayer L, Robbins J, Dworkind M, et al: Somatization and the recognition of depression and anxiety in primary care. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:734-741, 1993Link, Google Scholar

22. Mechanic D: Treating mental illness: generalist versus specialist. Health Affairs 9(4):61-75, 1990Google Scholar

23. Scheffler RM: Life in the kaleidoscope: the impact of managed care on the US health care work force and a new model for the delivery of primary care, in Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era. Edited by Donaldson MS, Yordy KD, Lohr KN, et al. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1996Google Scholar

24. Hart G, Wagner E, Pirzada S, et al: Physician staffing ratios in staff-model HMOs: a cautionary tale. Health Affairs 16(1):55-70, 1997Google Scholar

25. Scheffler R, Ivey S, Garrett B: Changing supply and earnings patterns of the mental health workforce. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, in pressGoogle Scholar

26. Donaldson MS, Yordy KD, Lohr KN, et al (eds): Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1996Google Scholar

27. AMA Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US, 1996-97 edition. Chicago, American Medical Association, 1997Google Scholar

28. Manderscheid R, Sonnenschein S (eds): Mental Health, United States, 1996. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1997Google Scholar

29. AAMC Data Book: Statistical Information Related to Medical Education. Washington, DC, American Association of Medical Colleges, 1995Google Scholar

30. Committee for the Advancement of Professional Practice, Practice Directorate, American Psychological Association: CAPP Practitioner Survey Results. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1996Google Scholar

31. Kohout J: Employment opportunities in psychology: current and future trends. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, Los Angeles, August 12-16, 1994Google Scholar

32. Dorwart R, Schlesinger M, Davidson H, et al: Changing Psychiatric Hospital Care: A National Study. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1990Google Scholar

33. Steenbarger B, Budman S: Group psychotherapy and managed behavioral health care: current trends and future challenges. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 46:297-309, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

34. Levenson H, Speed J, Budman S: Therapist's experience, training, and skill in brief therapy: a bicoastal survey. American Journal of Psychotherapy 49:95-117, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

35. Cummings N: Impact of managed care on employment and training: a primer for survival. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 26:10-15, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

36. Anderson D, Berlant J: Managed mental health and substance abuse services, in Essentials of Managed Health Care. Edited by Kongstvedt P. Gaithersburg, Md, Aspen, 1995Google Scholar