Childhood Experiences and Current Adjustment of Offspring of Indigent Patients With Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study reports the childhood experiences, current life situation and level of adjustment, and prior mental health service use of offspring of indigent people with schizophrenia. METHODS: Sixty-eight patient-parents were asked for consent for researchers to contact their adolescent and adult offspring. Thirty-nine consenting offspring were interviewed with an assessment battery that included measures of current occupational and social functioning, psychiatric status, and mental health service use. RESULTS: Interviewed offspring were raised in an average of three different settings from birth to 18 years of age. Relatives, particularly grandparents and aunts, were more likely to provide surrogate parenting than were nonkin foster parents and were more significant nurturing figures than biological parents. The typical offspring had a high school diploma, was gainfully employed, and was involved with a spouse or household partner or had a close friend. Twenty-three of the 39 offspring had children, and most were raising their children alone. Ten offspring had a diagnosis of major depression, schizoaffective disorder, or drug or alcohol abuse, but none had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Four of the ten offspring with a psychiatric diagnosis had never been treated. CONCLUSIONS: Findings underscore the need for long-term studies of families with a parent who is a psychiatric patient. Rehabilitation efforts should include extended family who play a critical role in raising offspring during periods when patient-parents are unable to do so. Offspring should be included in efforts to educate families about schizophrenia.

Parenthood was an uncommon life experience among people with severe mental illness during the era before deinstitutionalization, when they spent much of their adult lives within the walls of mental institutions. Before the late 1950s, fertility rates for people with schizophrenia were far below that of the general population (1), but marked increases have been observed in the era of deinstitutionalization (2-4). Some researchers have estimated that the fertility rate among women with severe mental illness is comparable to that of women in the general population (2).

We have no national estimates of the frequency with which men and women with severe mental illness procreate and care for their children. However, descriptive studies based on small, selected samples reveal that pregnancies are not always carefully planned (5-7), that a minority are responsible for care of their children (8), and that interruptions in parenting often occur in association with a chronic illness course and the need for hospitalization (9,10).

Severe mental illness has been linked to dysfunctional parenting (10-14). However, mental health professionals have become increasingly aware that the service system must address the fact that people with severe mental illness share the universal aspirations to form intimate relationships and have children (15-18). As clinicians put forth proposals to teach effective parenting skills to patients who are parents and who wish to raise their children (15,18), there is a need for more information on the life experiences of such offspring to guide policy and program development. Toward this end, we present data on the childhood experiences, current life situation and level of adjustment, and prior mental health service use of 39 adolescent and adult offspring of economically disadvantaged people with schizophrenia.

Methods

Procedures

Offspring contacted for this study were the sons and daughters of people with chronic schizophrenia who had been interviewed between 1988 and 1992 in New York City for an investigation of risk factors for homelessness (19,20). Among the interviewees were 158 parents—111 mothers and 47 fathers. We attempted to reach all of them one to two years after the original interview to ask for their consent to contact their children over age 13 and to elicit their help in locating the children. Offspring of consenting parents were located, and written voluntary informed consent (or written assent for subjects age 16 years or younger) was obtained.

Offspring were interviewed in 1994-1995 in New York City by mental health professionals trained to administer the assessment battery. Interviews lasted about two hours and were conducted in English or Spanish. Participants were paid an honorarium of $20 at the completion of the interview. The interview was designed to elicit information on childhood experiences, current physical and mental health and social adjustment status, and prior use of mental health services.

Instruments

A major objective of the study was to obtain a clear picture of an offspring's childhood experiences, particularly those that might be related to the parent's mental illness. We obtained a history of the offspring's living arrangements from birth to the present. The family section of the Community Care Schedule (21) was used to explore family characteristics during the subject's childhood and youth. This semistructured instrument gathers family historical data including family type (for example, single-parent or two-parent); episodes of neglect, abuse, or homelessness; and foster care placement.

A second objective was to describe the offspring's educational attainment, occupational status, level of social and psychological adjustment, and relationships with family and friends. The Community Care Schedule (21) elicited information on education, occupation, coping skills, family relationships, contacts with the criminal justice system, health status, and conjugal and parental adjustment, if applicable.

We used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (22) to probe for lifetime and current psychiatric diagnoses. The instrument allows evaluation of several domains of psychopathology, including affective disorders, psychotic disorders, alcohol and drug abuse or dependence, posttraumatic stress disorder, and conduct disorder or antisocial personality disorder.

To evaluate mental health service use, we asked about the offspring's experiences with mental health professionals who treated the parent, including what the offspring was told about the parent's illness and whether the offspring ever participated in family therapy with the parent. We also gathered information on the offspring's use of mental health services for a problem of his or her own.

We used descriptive statistics to examine the characteristics and experiences of offspring.

Findings

Getting access to offspring

We were able to gather information on the fate of 93 of the 158 patients who were parents. It was more difficult to locate patients with a history of homelessness, alcohol or drug abuse, or antisocial personality disorder. Our ability to locate patients was not related to whether the patient had ever lived with his or her offspring or whether the offspring had ever been placed in foster care.

From the pool of 93 subjects who could be relocated on follow-up, we eliminated patients with underage offspring and patients who had moved outside the region, who were currently hospitalized, or who were deceased. Of the remaining 68 patients who could be asked for permission to contact their offspring, 41, or 60 percent, agreed, and 27, or 40 percent, refused. We noted no differences in participation based on whether the patient had ever lived with his or her children, had ever been homeless, or had a child placed in foster care.

Characteristics of offspring

Demographic characteristics.

When we contacted the offspring of the 41 consenting parents, 39 (95 percent) agreed to be interviewed and two refused. Thirty-six of the 39 offspring who were interviewed (92 percent) were children of women patients.

Offspring were primarily female (29 offspring, or 74 percent), American born (37 offspring, or 95 percent), and raised in New York City (32 offspring, or 82 percent). The majority were members of a minority group: 23 were African American (59 percent), and 15 were Hispanic (38 percent). Most indicated that their religious preference was Protestant (17 offspring, or 44 percent) or Catholic (11 offspring, or 28 percent).

The age range was 13 to 48 years, and the median age was 26 years. More than two-thirds were single (27 offspring, or 69 percent), but nearly one-fifth were married or living with a partner (seven offspring, or 18 percent). Fourteen offspring, or 36 percent, had one child, and nearly one-fourth (nine offspring, or 23 percent) had two or more children. Only two offspring had ever served in the military.

The median level of education was 12 years, but nearly half had attended college. The majority (22 offspring, or 61 percent) were employed full or part time. The apparent success in educational endeavors for the group as a whole occurred even though a substantial minority had dropped out of high school (nine offspring, or 23 percent), were left back a grade (11 offspring, or 28 percent), were suspended from school (12 offspring, or 31 percent), or were often truant (14 offspring, or 36 percent). Only three offspring—two sons and one daughter—had ever spent time in prison or jail.

Childhood experiences.

Nearly all offspring were raised by the patient-parent for some time from birth to 18 years of age. However, changes in childhood living settings and relationships with nurturing adults were common. Only three offspring, or 8 percent, experienced no such changes. The offspring were raised in an average of three different settings, with a range from one to seven settings. Residential instability was typically associated with the patient's inability to care for offspring, precipitating foster care placement for ten offspring, or 29 percent, or care by relatives for 18 offspring, or 51 percent.

Corporal punishment was common in the settings in which offspring were raised. About half of the offspring (21 respondents, or 54 percent) reported having been hit with a belt, stick, or fist, and six offspring (15 percent) stated that they had been bruised or beaten. There were no gender differences in these reports. Eight subjects (21 percent) reported that they were raised in a setting in which one or more children was physically injured or sexually abused by a parent or adult in the household. For two offspring, the abuse was severe enough to have resulted in a child's being removed from the home by civil authorities. Only three offspring, or 8 percent, indicated that they had ever run away from home.

Experiences with parents with mental illness.

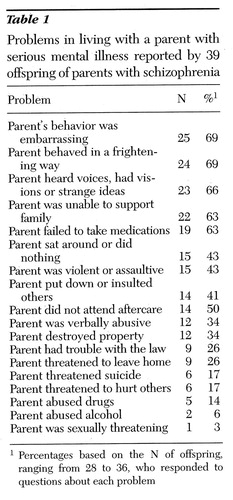

The offspring reported many problems in living with their parent who was a patient, even though they lived together intermittently. Evaluating their overall experience, more than three-quarters reported some problems with their parent (30 offspring, or 77 percent), and 21 offspring (54 percent) stated that there were many problems or serious problems. When asked about the most common problems, half or more of the offspring indicated that the parent's behavior was embarrassing or that the parent behaved in a frightening way, heard voices or had visions or strange ideas, was unable to support the family, or failed to take medications. Other common problems were that the parent sat around and did nothing all day, was violent or assaultive, put down or insulted others, and failed to attend aftercare. A list of these problems from most to least often reported is shown in Table 1.

Although all of the offspring we interviewed were aware that their parent suffered from a disabling emotional illness, their level of knowledge, attitudes, and specific experiences related to the disorder varied considerably. Only half (19 offspring, or 49 percent) had ever had an opportunity to talk about the illness with a mental health professional involved in the parent's treatment. Only one-quarter (ten offspring, or 24 percent) reported that as a child he or she had been told by a doctor that the parent suffered from schizophrenia. Others were given no specific information about the illness or no information at all. Slightly more than one-third (14 offspring, or 36 percent) reported receiving counseling from a mental health professional to help them deal with the parent's illness.

It is of interest that one in four (ten offspring, or 26 percent) believed that their parent would recover. The majority seemed convinced that their parent suffered from a lifelong illness.

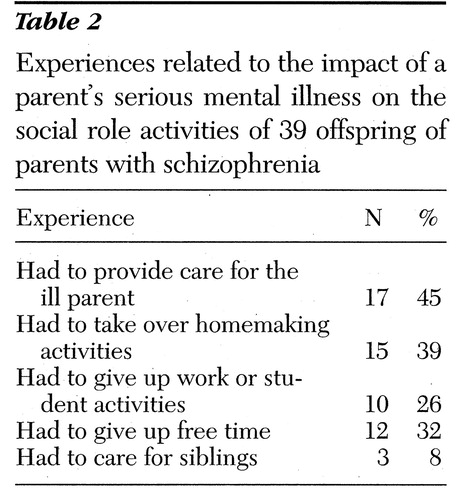

A substantial minority of the offspring played a caretaking role. Seventeen offspring, or 45 percent, indicated that they cared for their parent at some time. Nearly as many (15 offspring, or 39 percent) stated that their parent's inability to function demanded that they take over homemaking activities, a role shift requiring some to give up work or school activities (ten offspring, or 26 percent) or free time (12 offspring, or 32 percent). The impact of the parent's illness on the offspring's social role activities is shown in Table 2.

Relationship with the nonpatient parent.

We asked offspring about their relationship with their nonpatient parent, who was primarily their father. Slightly more than half (21 offspring, or 54 percent) had ever lived with their father for any period of time throughout childhood and adolescence. Living arrangements involving the father tended to be unstable, as the fathers of one-third of the offspring (13 respondents, or 33 percent) had never married the offspring's mother, and nearly one-half of the fathers (of 19 offspring, or 49 percent) were divorced or separated from the mother during the offspring's childhood.

About one-quarter (ten offspring, or 26 percent) did not know the current whereabouts of their father, and seven (18 percent) believed that their father was no longer living. Although nearly one in four had no information about their father's health status, 14 offspring, or 36 percent, indicated that he had an alcohol problem; 12, or 31 percent, that he was violent or abusive at home; 12, or 31 percent, that he had a serious health problem; seven, or 18 percent, that he had a mental or emotional problem; six, or 15 percent, that he had a drug problem; six, or 15 percent, that he had been in jail or prison; and four, or 10 percent, that he had been treated in a psychiatric hospital. Slightly more than one of four offspring with at least occasional contact with their father stated that they got along well or moderately well.

The most significant nurturing adult.

Only two offspring, or 5 percent, indicated that their nonpatient parent was the most significant nurturing adult during childhood and adolescence. Eleven offspring, or 28 percent, revealed that the parent with mental illness played this role in their lives.

However, biological parents were not as important for most offspring as were other relatives. Fifteen offspring, or 39 percent, told us that a grandparent was the most significant nurturing adult, and eight, or 21 percent, indicated that this person was an aunt or an uncle. Only one offspring reported that a foster parent played this role. Nearly three-quarters of the offspring (28 respondents, or 72 percent) stated that they currently got along well or moderately well with the most significant adult, and that this person gave them material support, including food, clothing, and shelter, as well as emotional support and companionship.

Current adjustment of offspring.

Most offspring were living in city apartments shared with family members. More than one-third (15 respondents, or 39 percent) were currently residing with the parent with mental illness. Although none of the offspring was currently homeless, nearly one-fifth (seven respondents, or 18 percent) reported an earlier episode of homelessness with an average duration of three to four months. Nearly half of those respondents experienced the episode of homelessness in the company of the parent with mental illness.

The majority of offspring (34 respondents, or 87 percent) had at least one close friend with whom to share life's ups and downs. Typically, the relationship was close enough to involve free and open discussions of important issues, including the nature and impact of the parent's illness. Few avoided discussing the parent's illness with a close friend because of embarrassment or fear of being misunderstood.

Eleven offspring, or 28 percent, were currently living with a partner who was gainfully employed and able to contribute to the household income. Eight offspring, or 21 percent, reported that they had experienced violence in their relationships with partners. Many offspring (23 respondents, or 59 percent) had children, and most were raising their children alone.

One in three offspring (13 respondents, or 33 percent) reported a current health problem that was usually not serious. The respondents varied considerably in overall mental health status. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores, which measure the extent to which any psychiatric symptom interferes with the ability to function in usual social roles, ranged from 38 to 90. The median score was 74, indicating that symptoms, if present, are transient and cause only slight impairment in social, occupational, or school functioning.

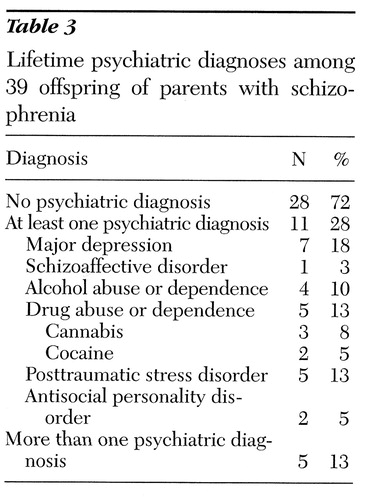

Depression was the most common symptom and syndrome. Fourteen offspring, or 36 percent, reported at least one episode in their lives when they felt depressed, sad, or blue most of the time every day for at least two weeks. For seven offspring, or 18 percent, the depression was severe enough to qualify them for a diagnosis of major depression (see Table 3). The prevalence of affective disorder among these offspring was nearly twice the lifetime prevalence in the general population (23).

Posttraumatic stress disorder was experienced by five offspring, or 13 percent. Four subjects, or 10 percent, received a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence, and five, or 13 percent, had a diagnosis of drug abuse. Thus the prevalence of drug abuse among these offspring was about double the lifetime prevalence in the general population (24). Only two offspring, or 5 percent, received a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder. It is of interest that one offspring received a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, and none received a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Three offspring, or 8 percent, had concurrent major depression or schizoaffective disorder and substance abuse.

Mental health treatment.

More than one-third of the offspring (15 respondents, or 39 percent) had received outpatient psychiatric treatment. Two offspring, or 5 percent, had received treatment in a psychiatric hospital, and four, or 10 percent, received some type of psychiatric medication.

Of the ten offspring with psychiatric diagnoses of major depression, schizoaffective disorder, or drug and alcohol abuse, six, or 60 percent, received some form of treatment, and four, or 40 percent, remained untreated. All untreated offspring had a diagnosis of major depression, and one also had concurrent substance abuse.

Discussion and conclusions

The mental health system long ignored the role of parenthood in the lives of people with severe mental illness (17,25). Recent studies have attempted to describe the parenting experiences of mothers with serious mental illness caring for their children (26). These exploratory studies have not included fathers who are patients and have no long-term follow-up data (9,16,27). Information on the fate of children of parents with severe mental illness has been lacking.

The study reported here contributes much-needed data about the life experiences and long-term adjustment of children of indigent patients with schizophrenia. It is, however, limited by the small sample size and the sample's lack of representativeness of the larger offspring group. The offspring we interviewed, daughters and sons of primarily residentially stable mothers, were functioning remarkably well and showed considerable resilience in the face of the difficult life circumstances they experienced in childhood and youth. Because of the way that subjects were selected for this study, it is possible that relatively well-adjusted offspring were overrepresented.

We would have liked to obtain information about the fate of more offspring of fathers with serious mental illness and of those whose parents were homeless or who had comorbid substance abuse or antisocial personality disorder. Because of the difficulty of relocating parents with these characteristics after a year or two, it may have been more feasible to study the offspring of patients currently enrolled in homeless shelters and mental health treatment programs.

Our study reveals that few parents who were patients were able to provide consistent, long-term parenting. Offspring were reared in several settings by different nurturing adults throughout childhood and adolescence. Any rehabilitation program focused solely on the relationship between patients and their offspring will be unlikely to reach the substantial numbers of offspring being reared in these out-of-home settings. Rehabilitation programs for parents with severe mental illness (18,28,29) should attempt to include the extended family, including grandparents and aunts and uncles, who play a critical role in caring for offspring during periods when the parents are unable to do so.

Future studies of patients' offspring should include control groups of children of people without severe mental illness. This comparison would facilitate examination of whether extended kin's often being the most significant nurturing adults for children of patients differs from normative child-rearing practices in various social and ethnic groups. It is our impression that in some groups the nurturing of children by extended kin is quite common.

Providers of mental health care should routinely gather information about the conjugal and parental aspects of patients' lives and should intervene to ensure that offspring are adequately cared for during periods of crisis in the patient's illness. Education about psychiatric illness and its treatments should be made available to offspring whenever they express an interest. Such education should incorporate research findings on the impact of severe mental illness on the lives of family members and offspring.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the New York Community Trust. The authors thank Omayra Bonilla, Louis Caraballo, Andrea Cassells, Boanerges Dominguez, Barbara Holton, and Elizabeth Margoshes.

Dr. Caton, Dr. Cournos, and Dr. Felix are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, 722 West 168th Street, New York, New York 10032. Dr. Wyatt is with the neuropsychiatry branch of the National Institute of Mental Health at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C. An earlier version of this paper was presented May 8, 1996, at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association held in New York City.

|

Table 1. Problems in living with a parent with serious mental illness reported by 39 offspring of parents with schizophrenia

1Percentages based on the N of offspring, ranging from 28 to 36, who responded to questions about each problem

|

Table 2. Experiences related to the impact of a parent's serious mental illness on the social role activities of 39 offspring of parents with schizophrenia

|

Table 3. Lifetime psychiatric diagnoses among 39 offspring of parents with schizophrenia

1. Erlenmeyer-Kimling L, Rainer JD, Kallman FJ: Current reproductive trends in schizophrenia, in Psychopathology of Schizophrenia. Edited by Hoch PH, Zubin J. New York, Grune & Stratton, 1966Google Scholar

2. Burr WA, Falek A, Strauss LT, et al: Fertility in psychiatric outpatients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 30:527-531, 1979Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Erlenmeyer-Kimling L, Nichol S, Rainer JD, et al: Changes in fertility rates in schizophrenic patients in New York State. American Journal of Psychiatry 125:916-927, 1969Link, Google Scholar

4. Shearer ML, Cain AC, Finch SM, et al: Unexpected effects of an "open door" policy on birth rates of women in state hospitals. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 138:413-417, 1968Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Coverdale JH, Aruffo JF: Family planning needs of female chronic psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:1489-1491, 1989Link, Google Scholar

6. Rudolph B, Larson GL, Sweeny S, et al: Hospitalized pregnant psychotic women: characteristics and treatment issues. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:159-163, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Miller LJ, Finnerty M: Sexuality, pregnancy, and childbearing among women with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services 47:502-506, 1996Link, Google Scholar

8. Test MA, Burke SS, Walisch LS: Gender differences of young adults with schizophrenic disorders in community care. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16:331-334, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. White CL, Nicholson J, Fisher WH, et al: Mothers with severe mental illness caring for children. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183:398-403, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Grunbaum L, Gammeltoft M: Young children of schizophrenic mothers: difficulties of intervention. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 63:16-27, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Rutter M: Children of Sick Parents: An Environmental and Psychiatric Study. Maudsley Monograph no 16, Institute of Psychiatry. London, Oxford University Press, 1966Google Scholar

12. Silverman M: Children of psychiatrically ill parents: a prevention perspective. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1257-1265, 1989Medline, Google Scholar

13. Quinton D, Rutter M: Family psychopathology and child psychiatric disorder: a four-year prospective study, in Longitudinal Studies in Child Psychology and Psychiatry: Practical Lessons From Research Experience. Edited by Nichol AR. Chichester, England, Wiley, 1984Google Scholar

14. Watt N, Anthony EJ, Wynne LC, et al (eds): Children at Risk for Schizophrenia: A Longitudinal Perspective. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1984Google Scholar

15. Apfel RJ, Handel MH: Madness and Loss of Motherhood: Sexuality, Reproduction, and Long-Term Mental Illness. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

16. Sands RG: The parenting experience of low-income single women with serious mental disorders. Journal of Contemporary Human Services 76:86-96, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Schwab B, Clark RE, Drake RE: An ethnographic note on clients as parents. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 15:95-99, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Nicholson J, Blanch A: Rehabilitation for parenting roles for people with serious mental illness. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 18:109-119, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Caton CLM, Shrout PE, Eagle PF, et al: Risk factors for homelessness among schizophrenic men: report of a case-control study. American Journal of Public Health 84:265-270, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Caton CLM, Shrout PE, Dominguez B, et al: Risk factors for homelessness among women with schizophrenia. American Journal of Public Health 85:1153-1156, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Caton CLM: The Community Care Schedule. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1989Google Scholar

22. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, First MB, et al: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

23. Weissman MM, Bruce ML, Leaf PJ, et al: Affective disorders, in Psychiatric Disorders in America. Edited by Robins LN, Regier DA. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

24. Anthony JC, Helzer JE: Syndromes of drug abuse and dependence, ibidGoogle Scholar

25. De Chillo N, Matorin S, Hallahan C: Children of psychiatric patients: rarely seen or heard. Health and Social Work 12:296-302, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Mowbray CT, Oyserman D, Zemencuk JK, et al: Motherhood for women with serious mental illness: pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 65:21-38, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Wang AR, Goldschmidt VV: Interviews of psychiatric inpatients about their family situation and young children. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 90:459-465, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Cohler B, Musick J (eds): Intervention With Psychiatrically Disabled Parents and Their Young Children. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 24, 1984Google Scholar

29. Blanch AK, Nicholson J, Purcell J: Parents with severe mental illness and their children: the need for human service integration. Journal of Mental Health Administration 21:388-396, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar