Outcomes of Homeless Mentally Ill Chemical Abusers in Community Residences and a Therapeutic Community

Abstract

Objectives: The feasibility and effectiveness of treating homeless mentally ill chemical abusers in community residences compared with a therapeutic community were evaluated. METHODS: A total of 694 homeless mentally ill chemical abusers were randomly referred to two community residences or a therapeutic community. All programs were enhanced to treat persons with dual diagnoses. Subjects' attrition, substance use, and psychopathology were measured at two, six, and 12 months. RESULTS: Forty-two percent of the 694 referred subjects were admitted to their assigned program and showed up for treatment, and 13 percent completed 12 months or more. Clients retained at both types of program showed reductions in substance use and psychopathology, but reductions were greater at the therapeutic community. Compared with subjects in the community residences, those in the therapeutic community were more likely to be drug free, as measured by urine analysis and self-reports, and showed greater improvement in psychiatric symptoms, as measured by the Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression Scale and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Their functioning also improved, as measured by the Global Assessment of Functioning scale. CONCLUSIONS: Homeless mentally ill chemical abusers who are retained in community-based residential programs, especially in therapeutic communities, can be successfully treated.

Large numbers of mentally ill chemical abusers counted in hospitals (1), drug rehabilitation centers (2), city streets (3), and general population surveys (4) are challenging traditional approaches to the delivery of psychiatric care (5). Historically, major mental illness and substance abuse have been treated in separate systems with differing and sometimes contradictory orientations (6). Due to structural divisions in the delivery of psychiatric and substance abuse treatment, mentally ill chemical abusers, who need both types of help, are not likely to find it in either system (7).

In traditional psychiatric settings, substance abuse is underdiagnosed, downplayed, or treated ineffectively (8); in drug rehabilitation centers, mental illness is overlooked or treated in a cursory manner (9). Often mentally ill chemical abusers are shuffled between psychiatric and substance abuse rehabilitation programs, using scarce resources from both types of facilities but benefiting from neither (10).

Successfully treating these individuals is further complicated in both settings by their severe and complicated symptoms (11) and by the fact that a significant proportion are chronically homeless (12), which may diminish the odds of their being retained in treatment (13).

Innovative models for integrating mental illness and substance abuse services have been implemented in a variety of outpatient settings (14), and a literature is emerging on the effectiveness of treating mentally ill chemical abusers in various types of programs (15-21). However, research has been hampered by methodological problems, especially high attrition rates from studies with initially small sample sizes, and the effectiveness of treating this population in any type of treatment modality has not been demonstrated sufficiently (22).

Against this background of debate about where and how mentally ill chemical abusers should be treated, we report the results of a large-scale, quasiexperimental study designed to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of treating this population in two contrasting community-based milieus—a community residence program and a therapeutic community (23). Both were enhanced to treat mental illness and substance abuse simultaneously. In most communities a variety of options exist for treating mentally ill chemical abusers, including case management, outpatient therapies, and 12-step programs. However, a comparative analysis of the community residence program and the therapeutic community is important because of the radically different approaches to treatment in these two types of programs.

Community residences were started in the 1960s by middle-class families of deinstitutionalized mental patients, and they have emerged as an important modality for treating mental disorders in metropolitan areas (24). The aim of such programs is to provide the least restrictive alternative to psychiatric hospitals, with appropriate levels of counseling, supervision, and medical assistance. Abstinence from alcohol and other drugs is expected, but relapses are tolerated. Residents commute to day programs, and they are therefore in daily contact with the outside world. Community residences are widely regarded as effective alternatives to inpatient psychiatric hospitalization (25), but the success of this treatment modality among mentally ill persons with a history of homelessness has been questioned (13).

The two community residences included in this study previously treated only persons with psychiatric disorders, but they have been enhanced by the addition of substance abuse counselors and training for the staff in the treatment of mentally ill chemical abusers. The projected duration of treatment is about 18 months.

Therapeutic communities were started in North America in the 1960s for the treatment of substance abuse, but they are becoming increasingly popular modalities in treating a broad array of psychiatric disorders (26). In contrast to community residences, the therapeutic community may be characterized as a "high-demand" environment where privileges and rules of conduct are well defined, abstinence from alcohol or other drugs is a principal prerequisite, and a global change in lifestyle is the ultimate goal (27).

Treatment in a therapeutic community occurs in an "extended family" of peers, counselors, and professionals where emotional support is exchanged while values of abstinence and self-reliance are upheld (28). The provision of support in the context of well-defined values forms the basis for a renewed sense of motivation and self-esteem and, ultimately, abstinence from drugs and improved mental health. All treatment is provided in-house, and the residents are therefore insulated from the outside world.

The therapeutic community in this study was modified by addition of psychiatric treatment amenities to the substance abuse treatment components generally found in traditional therapeutic communities. The staff includes psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric social workers, and substance abuse counselors who together have developed an integrated model for treating mentally ill chemical abusers. The particular therapeutic community in this study, described by McLaughlin and Pepper (29), is the long-term traditional type (26). The projected duration of treatment is 18 months.

Although the traditional, long-term therapeutic community has been proclaimed effective in treating a broad range of psychiatric disorders (26,27, 30), the high levels of environmental stimuli found in such communities have been deemed inappropriate for some mentally ill persons (31,32). Indeed, substance abusers with severe psychiatric impairment were found to be poor candidates for a short-term therapeutic community associated with a Veterans Affairs hospital (33).

We examined the extent to which homeless mentally ill chemical abusers randomly referred to a community residence or a therapeutic community were successfully enrolled in their assigned program and, if they started treatment, the extent to which they experienced reduced levels of substance use and psychopathology.

Methods

Sample and research design

In 1990 Argus Community, Inc., in the South Bronx launched one of the pioneer initiatives to provide and evaluate treatment for mentally ill chemical abusers in New York City (23). Homeless men with a major mental disorder and a history of substance abuse were recruited for this treatment evaluation from hospitals, clinics, shelters, the court system, and other agencies in contact with mentally ill chemical abusers. Data collection for the study began in June 1990 and ended in June 1995. To be included in the treatment evaluation, clients had to be male, homeless, and at least 21 years of age. They had to have a major DSM-III-R diagnosis, at least two psychiatric hospitalizations, and a confirmed history of abusing alcohol or other drugs.

Clients were excluded from the evaluation based on broadly defined admission standards of the participating community residences and therapeutic community. They included lack of motivation for long-term treatment, inability to complete the screening interview (due typically to cognitive disorganization), extreme psychotic ideation, and a history of violence. Using these broad screening criteria, 694 homeless mentally ill chemical abusers were randomly referred to either a therapeutic community or a community residence for treatment of their psychiatric and substance abuse problems.

Comparing different types of treatment with an experimental design is seldom possible in field studies of substance abuse treatment (34), and, indeed, our study deviates from a true experiment in certain respects. Random assignment was designed generally to achieve equal numbers of referrals to both treatment modalities, but variations in bed availability at the two programs made an equal assignment formula unworkable.

During periods when beds were relatively unavailable at the community residences, the allocation proportions were shifted toward the therapeutic community—75 percent to the therapeutic community and 25 percent to the community residences—resulting in a larger number of referrals to the former. The proportions of screened mentally ill chemical abusers starting treatment in the two programs were skewed further toward the therapeutic community because clients referred there were more likely to enter treatment, primarily because of the longer waiting and processing delays at the community residences.

Finally, even though clients were screened with regard to broadly defined admission policies, the treatment facilities retained the final say about acceptance of referred clients. The selection of screened clients into treatment by the facilities, in addition to the client's self-selection to treatment, is analyzed in some detail in this report, and the evaluations of treatment outcomes among those engaged in treatment are considered in the context of this broad analysis.

Measurement of variables

All clients were screened by interviewers who carried out a baseline assessment before the client was assigned to a program. The interviewers were trained and monitored by one of the authors (JJR), a clinical psychologist. They conducted follow-up interviews after clients had been in treatment for two, six, and 12 months. For pragmatic reasons, the interviewers were not blind to the client's treatment modality at the follow-up assessments. Most interviews were conducted at Argus Community. Baseline interviews lasted about one hour and 45 minutes; follow-up interviews lasted about an hour. Baseline and follow-up interviews with a client were not necessarily conducted by the same interviewer.

Pretreatment severity of alcohol and other drug problems was measured using two subscales of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (35). Following the investigators' coding protocol, we combined measurements of the number of days that substances were used during the past month (for hospitalized clients the 30 days before hospitalization), the client's self-perceived problem with the drug, and the self-perceived need for treatment, with equal weighting, yielding a score ranging from .00 to 1.00, with higher scores indicating greater severity. The two scales, for alcohol and other drugs, are combined in the analysis below.

During the course of treatment, substance abuse was monitored by both urine analysis and self-reported use. In both treatment settings, urine analyses were conducted to detect or verify suspected substance use. Results of these tests are reported here for a subsample of residents at the community residences and the therapeutic community. Self-reports of substance use after two, six, and 12 months of treatment, based on a subsection of the ASI, are also provided.

Assessments of psychopathology were obtained during the screening interview and again after two, six, and 12 months of treatment. Depression, anxiety, agoraphobia, psychotic ideation, general psychiatric status, and level of functioning were examined.

The 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to measure depressive symptoms (36). Typical items refer to mood, energy level, appetite, and self-esteem. The response categories range from 0, rarely, to 3, most or all of the time. CES-D scores of 20 or higher have been indicative of clinical depression in studies of the general population (37). Items were added to form an internally consistent scale; baseline scores for the sample ranged from 0 to 58 (Cronbach's alpha=.86).

Agoraphobia was measured by four items, devised for the study, that reflected the anxiety potential of public encounters. For example, one item asked, Have you avoided the subway or being in a crowd because you might get an attack of fear or anxiety? Response categories ranging from 0, never, to 4, very often, were summed to form a total score; baseline scores for the sample ranged from 0 to 16 (Cronbach's alpha=.75).

Psychotic ideation (hallucinations, delusions, and paranoid thinking) was measured by ten items adapted from an instrument developed by Dohrenwend and associates (38). Response categories range from 0, never, to 4, very often. Items were summed to form a highly reliable scale; baseline scores ranged from 0 to 40 (Cronbach's alpha = .88). The time frame for both the psychotic ideation and the agoraphobia scales, which was one year during the screening interview, was changed to "the period of time since the last interview" for the follow-up evaluations.

The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) was used to measure current psychiatric status (39). Self-reports were elicited about nine psychiatric symptoms, such as exaggerated somatic preoccupation, unreasonable feeling of guilt, and hallucinatory behavior. Behavioral ratings were coded for emotional withdrawal, motor retardation, disorientation, and so forth. The 18 self-reported or interviewer-observed items, with coding categories from 1, not reported or not observed, to 7, very severe, were combined to form an aggregate BPRS score; baseline scores for the sample ranged from 18 to 60 (Cronbach's alpha=.73).

Anxiety was measured using a subscale of the BPRS. Items included were the self-report of feeling "anxious or tense" during the past week and ratings of excitement (heightened emotional tone) and tension (motor restlessness) made during the interview. The three items were summed to form a total scale; baseline scores ranged from 3 to 19, with a weak but acceptable level of reliability (Cronbach's alpha=.52).

The Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF) was used to rate overall psychiatric disturbance (40). Interviewers rate clients on a scale ranging from 1, the sickest possible individual, to 100, the healthiest. The GAF is divided into ten equal intervals based on clinical protocols describing individuals within each decile. Baseline scores for the sample ranged from 30 to 61.

The validity of the high-demand versus low-demand distinction between the therapeutic community and the community residence was examined empirically with the 100-item Community-Oriented Programs Environment Scale (COPES) (41), which reflects ten dimensions of the treatment climate, such as program involvement, support, autonomy, and program clarity. The items, with response categories of no (scored 0) and yes (scored 1), were reverse coded as necessary and added to form ten internally consistent subscales for the client's perception of the treatment environment. Higher scores indicated more demand.

Statistical procedures

The analysis was performed using STATA, Release 3.1, for DOS (42). Changes in substance abuse were gauged from reductions in the percentages of substance users at various time points. Changes in psychopathology were analyzed by using paired t tests to compare baseline mean scores on the measures of psychopathology with mean scores observed during treatment. The effects of the treatment modality on changes in psychopathology were quantified with a regression approach to the analysis of change.

The effects on attrition of baseline measurements of homelessness, substance abuse, and psychopathology, both before and after admission to treatment, were examined with multinomial logistic regression (43). Unlike ordinary logistic regression, which analyzes dichotomous outcomes, multinomial logistic regression incorporates multicategory outcomes. The comparisons are between a predictor variable (for example, years of homelessness) and a particular outcome category, using a base category as a reference point (for example, attrition between two and six months relative to the reference category of "no attrition"). The associations are expressed in terms of risk ratios.

The analysis entailed multiple comparisons across variables and time points, which inflated the chances of type I error, falsely observing untrue associations. This bias was controlled with a Bonferroni correction (p value of .05 divided by the number of comparisons in a particular analysis). Because of reductions in the number of clients remaining in treatment at later time points (attrition), type II error, failing to observe true associations, was also a problem in this data set. Associations statistically significant at the .05 and .01 levels are therefore reported here, with the caveat that they should be viewed as tentative.

Results

Sample description

The 694 treatment candidates were typically young, poorly educated, and nonwhite. Their mean±SD age was 31±5.2 years. Only 11.7 percent had more than a high school education. A total of 57.9 percent were African American, and 21.3 percent were Hispanic. Almost half (42 percent) had five or more previous psychiatric hospitalizations.

The major substance of abuse was crack for 43.9 percent, alcohol for 21.2 percent, and cocaine (not crack or freebase) for 13.2 percent. Most of these mentally ill chemical abusers (87.6 percent) reported multiple substance use, and 45.8 percent of them were classified in their psychiatric dossiers as "chronically addicted."

About half of the treatment candidates (48.8 percent) had a primary diagnosis of a nonaffective psychotic disorder (schizophrenia, all types, and delusional disorders). About a fourth (22.3 percent) had a primary diagnosis of a depressive disorder (major depression, bipolar disorder, and dysthymia). Most of the mentally ill chemical abusers also had a second diagnosis, which was in most cases a substance use disorder (abuse or dependence) (63.5 percent).

Following our research protocol, all of the treatment candidates were, in a broad sense, homeless. About a fourth (25.3 percent) lived on the streets or stayed in a city-provided shelter at least 14 of 60 days immediately before their hospitalization or referral to Argus Community. About a third (37.4 percent) were deemed to be currently homeless because of difficulties in securing living arrangements.

High levels of psychopathology were observed during the screening interview. The typical respondent reported a level of depressive symptoms that indicated clinical depression; among the 694 referrals the mean± SD score on the CES-D was 22.9± 8.2. The need for psychiatric care and supervision was reflected in the mean±SD rating of 43.26±15.2 on the GAF. Because of random assignment, no statistically significant difference in psychopathology was found at baseline between those referred to the community residences and the therapeutic community.

Description of the treatment environments

Differences in the two treatment environments were found on six of the COPES subscales, which were administered to residents who were in treatment at least six months. Consistent with the distinction between high and low demand, the mean rating of the therapeutic community residents indicated a higher level of order and organization than the rating of those in the community residences (7.44±2.78 versus 6.74±2.71; t=2.06, df=154, p= .032). Staff control was also rated higher (7.87±2.51 versus 6.85±2.31; t= 2.16, df=154, p=.028).

The therapeutic community was portrayed as an extended family by its residents' higher mean ratings on involvement (6.96±2.81 versus 5.80± 2.58 for those in the community residences; t=2.20, df=154, p=.021), support (7.10±2.96 versus 5.67±2.15; t=3.20, df=154, p=.002), and personal problem orientation (7.10±2.52 versus 5.60±1.14; t=2.40, df=154, p= .019). The higher mean rating on anger and aggression among the therapeutic community residents (6.26±2.36 versus 5.47±2.14; t=2.06, df=154, p= .032) reflects the therapeutic community's emphasis on the expression of emotion during treatment.

Treatment attrition

More than half (58 percent) of the screened clients did not start treatment in the assigned program. Among the 373 referrals to the therapeutic community, 84 (23 percent) were rejected for admission by the facility, and 120 (32 percent) failed to show up at the facility either before or after the scheduled placement interview. Of the 321 referrals to the community residences, 73 (23 percent) were rejected by the facilities, and 127 (40 percent) failed to show up for treatment.

Of the 169 residents who started treatment in the therapeutic community, 123 (73 percent) completed two months of treatment, 72 (43 percent) completed six months, and 43 (25 percent) completed 12 months. Of the 121 residents who started treatment in the community residences, 106 (88 percent) completed two months of treatment, 67 (55 percent) completed six months, and 45 (37 percent) 12 months.

Postadmission attrition arose mostly from clients' leaving treatment against medical advice. However, about 10 percent of the dropouts were discharged by the facility for failure to comply with rules.

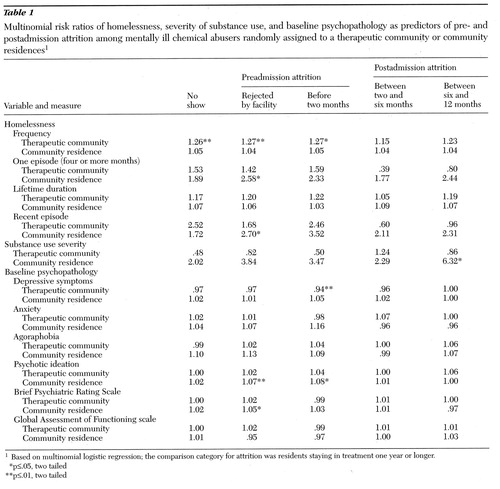

Table 1 shows the multinomial risk ratios between measurements of homelessness, substance abuse severity, and baseline psychopathology and pre- and postadmission attrition by clients assigned to the two treatment modalities. Mentally ill chemical abusers who were frequently homeless were lost from treatment at the therapeutic community. (Being lost from treatment was defined as failure to keep the initial appointment, rejection by the facility, or dropout during the first two months). Recently homeless persons and those with a long episode of homelessness (four months or more) were disproportionately rejected for admission at the community residences.

Mentally ill chemical abusers with severe levels of substance abuse, as measured by the ASI subscales, were somewhat less likely to be lost from treatment at the therapeutic community than those with less severe levels (p≤.10). However, those with severe levels of substance abuse tended to be lost from treatment at the community residences (a risk ratio of 6.32 for dropout between six and 12 months).

Highly depressed individuals, as measured by the CES-D, were less likely to drop out of the therapeutic community during the first two months of treatment (risk ratio=.94); 1-point increments on the CES-D (range of 0 to 58) were associated with 6 percent reductions in the odds of dropout. Highly psychotic clients, as measured by the scale adapted from Dohrenwend's study (38), tended to be rejected for admission to the community residence (risk ratio=1.07), and, if admitted, they tended to drop out of treatment during the first two months (risk ratio=1.08).

None of the risk ratios cited above were statistically significant with the conservative Bonferroni correction (.05/110=.0005). The general conclusion is that homelessness, substance use, and psychopathology were generally not associated with attrition at the therapeutic community or the community residence. The different effects of depressive symptoms on attrition at the therapeutic community and the community residence are nonetheless noteworthy.

Reductions in substance use

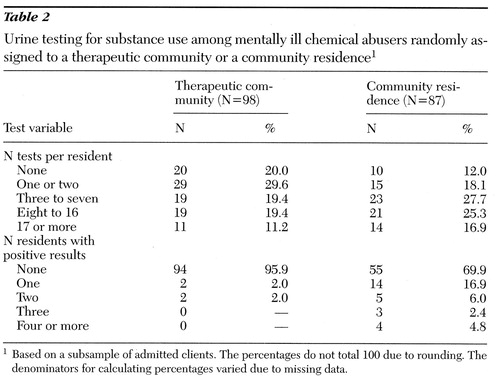

Table 2 summarizes the results of urine testing for substance use, using a subsample of subjects at the community residences (N=87) and the therapeutic community (N=98). The median number of tests during the course of treatment was six at the community residences and 2.50 at the therapeutic community (p≤.01, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for the difference between distributions). Among the 87 clients tested in the community residences, 30.1 percent had a positive urine screen at some point during treatment; this figure was 4.1 percent among the 98 clients tested in the therapeutic community (p≤.01, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). The two comparisons shown in Table 2 were significant with the Bonferroni correction (.05/2=.025).

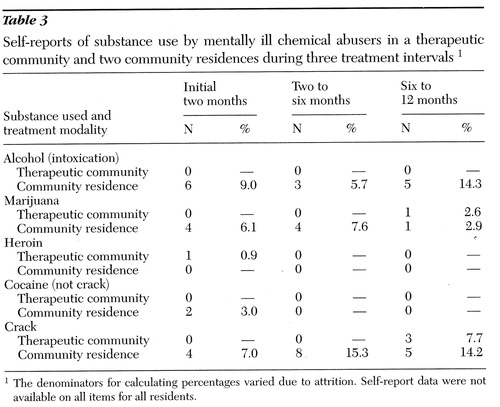

Table 3 summarizes the self-reported use of substances during treatment among residents who completed two, six, and 12 months of treatment. Between six and 12 months, 14.3 percent of clients in the community residences reported using alcohol, 2.9 percent reported using marijuana, and 14.2 percent reported crack use. During the same time frame, none of the therapeutic community residents reported alcohol use, 2.6 reported marijuana use, and 7.7 percent reported using crack. Chi square tests indicated that the differences in alcohol and crack use between treatment modalities were significant (p≤.05). However, none of the differences between treatment modalities shown in Table 3 were statistically significant with a Bonferroni correction (.05/15=.003) because of the number of comparisons and low frequencies.

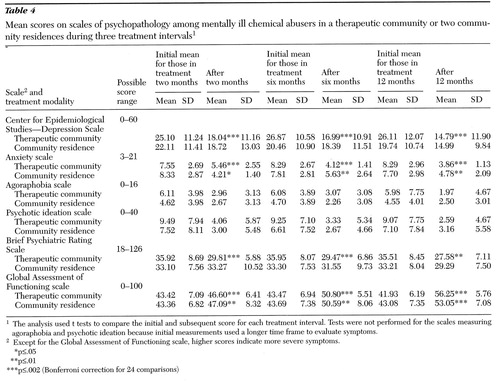

Reductions in psychopathology

Mean values for the measures of psychopathology were compared across three time intervals of treatment—baseline to two months, two to six months, and six to 12 months. As Table 4 shows, across all the time periods, reductions in depressive symptoms measured by the CES-D and reductions in general psychiatric symptoms measured by the BPRS were significant for residents in the therapeutic community but not for those in the community residences. Improvements in anxiety and functioning as measured by the GAF were significant across all time intervals in both treatment modalities. The reductions in psychopathology for therapeutic community residents were statistically significant with the Bonferroni correction (.05/24=.002).

Tests of statistical significance were not performed for changes in symptoms of agoraphobia and psychotic ideation because of altered time periods for evaluating these symptoms before and after treatment. However, reductions in the mean values for those symptoms were more pronounced for residents of the therapeutic community.

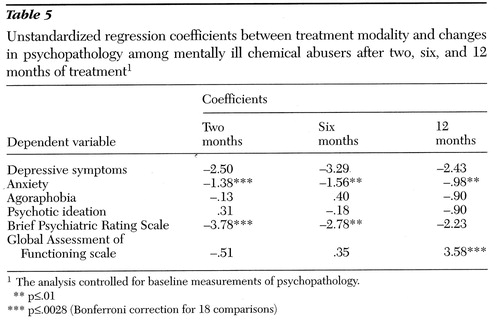

A regression analysis for the effects of the treatment modality (the therapeutic community) on changes in psychopathology after two, six, and 12 months of treatment is summarized in Table 5. Levels of psychopathology at a given time during treatment were predicted from the treatment modality, with baseline measurements of psychopathology statistically controlled. Treatment type, the independent variable in the analysis, was dummy coded, with the therapeutic community coded high (therapeutic community=1, community residences=0).

In this analysis, treatment at the therapeutic community was associated with comparatively greater improvement in anxiety, psychiatric symptoms measured by the BPRS, and level of functioning measured by the GAF. The Bonferroni correction indicated that improvements in anxiety and BPRS symptoms after two months and the level of functioning after 12 months were significantly greater among therapeutic community residents.

Discussion and conclusions

We studied the treatment of mentally ill chemical abusers in community residences and a therapeutic community. Treatment was enhanced in all programs to provide both psychiatric and substance abuse services. Program descriptions of the community residence as a low-demand approach to treatment and the therapeutic community as a high-demand approach were validated based on residents' perceptions of the treatment environment as measured by the COPES (41).

The effectiveness of treating mentally ill chemical abusers with these contrasting approaches to treatment was based on a quasiexperimental design in which screened clients were randomly referred to either a therapeutic community or a community residence and subsequently monitored in terms of attrition, substance use, and psychopathology. The study was based on males only, and the findings may not apply to females.

High rates of attrition both before and after admission to treatment compromised the experimental design. However, the associations between attrition and the outcome variables for this study were examined, and the extent to which attrition may have biased our findings may therefore be evaluated. Initial levels of psychopathology only weakly predicted which clients would be lost to treatment—that is, those who did not keep the initial admission appointment, who were rejected by the facility, or who dropped out during the first two months of treatment. Indeed, severely depressed residents were inclined to stay in the therapeutic community.

Our detailed analysis of pre- and postadmission attrition has both substantive and methodological implications. Substantively, the generally weak associations between attrition and psychopathology suggest that rather impaired mentally ill chemical abusers can be successfully placed and engaged in community-based residential programs. Methodologically, these data suggest that the observed reductions in substance abuse or dependence and psychopathology were not artifacts of selective attrition; that is, they did not occur only because the most impaired left treatment.

Because of differences in preadmission attrition, clients starting treatment at the therapeutic community and at the community residences were not identical in psychopathology. Therapeutic community clients tended to be somewhat more impaired initially, especially with regard to depressive symptoms. Because therapeutic community clients initially had higher scores than community residence clients, the differences in changes in these scores during treatment may partly reflect a regression to the mean—the tendency for extreme scores to be less extreme when remeasured. However, it seems unlikely that regression to the mean would have entirely accounted for the greater reductions in psychopathology among therapeutic community residents given the small differences between groups in baseline psychopathology.

The mentally ill chemical abusers in this study were severely impaired initially in terms of both mental illness and chemical abuse, but marked reductions in these afflictions were observed during the course of treatment at both the community residences and the therapeutic community. Most but not all of the residents achieved abstinence from alcohol and other drugs during treatment, as measured by both urine analysis and self-reports. Clients in both programs showed improvements on broad measures of psychopathology (the BPRS and GAF).

However, reductions in both substance use and psychopathology were generally more significant among therapeutic community residents. They were more likely to achieve and maintain sobriety. They showed greater reductions in depressive symptoms and anxiety and a greater improvement in general functioning (measured by the GAF).

The comparative effectiveness of the therapeutic community in reducing substance use and psychopathology must be viewed in conjunction with the higher postadmission attrition in that setting compared with the community residences, especially during the two-month orientation phase. On balance, however, the effectiveness of treating mentally ill chemical abusers in the therapeutic community was nonetheless surprising given the widely accepted notion that severely impaired individuals are poor candidates for high-demand treatment approaches; more specifically, McLellan (33) found that substance abusers with severe psychiatric symptoms were poor candidates for treatment in a short-term therapeutic community associated with a VA hospital. Unlike McLellan's subjects, the subjects in the study reported here suffered from multiple problems of mental illness, substance abuse, and homelessness, and the therapeutic community was the traditional long-term type, shown to be the most effective in previous studies (26), which was modified to treat individuals with dual disorders.

The effectiveness of treating mentally ill chemical abusers in the therapeutic community centered around depressive symptoms in two ways: residents with initially high scores on the CES-D were inclined to stay in the therapeutic community, and marked declines in CES-D scores were observed during the course of treatment. How do we explain the affinity of depressed mentally ill chemical abusers for the high-demand therapeutic community in this study? We suggest that it is because this modality combines a demanding approach to treatment with other aspects of treatment that depressed residents in particular may find appealing, such as social support and coordination of services. The "resocialization" of therapeutic community residents entails the mutual exchange of emotion and support. Rebuilding motivation and self-esteem, even in a context of highly structured rules, may resonate with the needs of highly depressed individuals.

The in-house delivery of psychiatric services may also be important. At the therapeutic community, psychiatrists, psychologists, and nurses provide professional care and assistance on demand, an approach that may resonate with the needs of highly depressed individuals.

The issue of matching clients and treatment facilities is much debated in the literature (44). Despite concerns about treating mentally ill persons and mentally ill chemical abusers in traditional therapeutic communities, this study suggests that matching severely depressed mentally ill chemical abusers with this type of treatment may offer advantages.

In sum, like findings of previous studies, our findings highlight the problem of treatment attrition among mentally ill chemical abusers. However, if these severely impaired individuals are maintained in treatment, there is some reason for optimism about treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jacob Cohen for reviewing an earlier draft of the paper. This research was supported by award DA-06968-93 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

When this work was done, Dr. Nuttbrock was a research scientist, Dr. Rivera was a clinical psychologist, and Ms. Ng-Mak was a research associate at Argus Community, Inc., in New York City, where Dr. Rahav is director of research. Dr. Nuttbrock is currently a project director at the National Development and Research Institutes, 2 World Trade Center, New York, New York 10048. Dr. Rivera is now affiliated with the Mt. Sinai School of Medicine. Ms. Ng-Mak is a fellow in the psychiatric epidemiology training program at Columbia University. Dr. Link is a research scientist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and associate professor at the Columbia University School of Public Health.

|

Table 1. Multinomial risk ratios of homelessness, severity of substance use, and baseline psychopathology as predictors of pre- and postadmission attrition among mentally ill chemical abusers randomly assigned to a therapeutic community or community residences1

1Based on multinomial logistic regression; the comparison category for attrition was residents staying in treatment one year or longer.

|

Table 2. Urine testing for substance use among mentally ill chemical abusers randomly assigned to a therapeutic community or a community residence1

1Based on a subsample of admitted clients. The percentages do not total 100 due to rounding. The denominators for calculating percentages varied due to missing data.

|

Table 3. Self-reports of substance use by mentally ill chemical abusers in a therapeutic community and two community residences during three treatment intervals 1

1The denominators for calculating percentages varied due to attrition. Self-report data were not available on all items for all residents.

|

Table 4. Mean scores on scales of psychopathology among mentally ill chemical abusers in a therapeutic community or two community residences during three treatment intervals1

1The analysis used t tests to compare the initial and subsequent score for each treatment interval. Tests were not performed for the scales measuring agoraphobia and psychotic ideation because initial measurements used a longer time frame to evaluate symptoms.

2 Except for the Global Assessment of Functioning scale, higher scores indicate more severe symptoms.

*p≤.05

**p≤.01

***p≤.002 (Bonferroni correction for 24 comparisons)

|

Table 5. Unstandardized regression coefficients between treatment modality and changes in psychopathology among mentally ill chemical abusers after two, six, and 12 months of treatment1

1The analysis controlled for baseline measurements of psychopathology.

**p≤.01

***p≤.0028 (Bonferroni correction for 18 comparisons)

1. Kiesler CA, Simpkins CG, Morton TL: The prevalence of dual diagnoses of mental and substance abuse disorder in general hospitals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:400-403, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Rounsaville BJ, Antoa SF, Carroll K, et al: Psychiatric diagnoses of treatment-seeking cocaine abusers. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:43-51, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Susser E, Struening EL, Canover S: Psychiatric problems in homeless men: lifetime psychosis, substance use, and current distress in new arrivals at New York City shelters. Archives of General Psychiatry 46:845-850, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhoa S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19, 1995Google Scholar

5. Osher FC, Kofoed LL: Treatment of patients with psychiatric and psychoactive substance use disorders. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1025-1030, 1994Google Scholar

6. Kofoed LL, Kanla J, Walsh T, et al: Outpatient treatment of patients with substance abuse and co-existing psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 143:467- 472, 1986Google Scholar

7. Thacker S, Mandelbrote B: System issues in serving the mentally ill substance abuser: Virginia's experience. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:146-149, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Galanter M, Engelko M, Engelko S, et al: Crack/cocaine abusers in the general hospital: assessment and initiation of care. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:810-815, 1992Link, Google Scholar

9. Hoffman GW, DiRito DC, McGill EC: Three-month follow-up of 28 dual diagnosis inpatients. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 19:79-86, 1992Google Scholar

10. Ridgely MS: Creating integrated programs for severely mentally ill persons with substance abuse problems. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 50:29-41, 1991Google Scholar

11. Carey MP, Carey KB, Meisler AW: Psychiatric symptoms in mentally ill chemical abusers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 179:136-138, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Rahav M, Link BG: When social problems converge: homeless, mentally ill, chemical misusing men in New York City. International Journal of the Addictions 30:1019- 1042, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Caton CL, Wyatt RJ, Felix A, et al: Follow-up of chronically homeless mentally ill men. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1639- 1642, 1993Link, Google Scholar

14. Kline J, Harris M, Bebout RR, et al: Contrasting integrated and linkage models of treatment for homeless, dually diagnosed adults. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 50:95-106, 1991Google Scholar

15. Jerrell JM, Ridgely MS: Evaluating changes in symptoms and functioning in dually diagnosed clients in specialized treatment. Psychiatric Services 46:233-238, 1995Link, Google Scholar

16. Wolpe PR, Gortor G, Serota R, et al: Predicting compliance of dual diagnosis inpatients with aftercare treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:45-49, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

17. Teague GB, Drake RE, Ackerson TH: Evaluating use of continuous treatment teams for persons with mental illness and substance abuse. Psychiatric Services 46:689-695, 1995Link, Google Scholar

18. Bartels SJ, Drake RE, Wallach MA: Long-term course of substance use disorders among patients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:248-251, 1995Link, Google Scholar

19. Moos RH, Moos BS: Stay in residential facilities and mental health care as predictors of readmission for patients with substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services 46:66-72, 1995Link, Google Scholar

20. Bartels SJ, Drake RE: A pilot study of residential treatment for dual diagnoses. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 184:368- 381, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Walker RD, Howard MO, Lambert MD, et al: Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of veterans with substance use disorders. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:232-2 37, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

22. Drake RE, Meuser KT, Clark RE, et al: The course, treatment, and outcome of substance disorder in persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:42-51, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Rahav M, Rivera J, Collins JC, et al: Bringing experimental research designs into existing treatment programs: the case of community-based treatment for the dually disordered, in Innovative Treatment Strategies. Edited by Inciardi JA, Timms F, Fletcher B. Westport, Conn, Greenwood, 1992Google Scholar

24. Arce AA, Vergare M: An overview of community residences as alternatives to hospitalization. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 8:423-436, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Coursey RD, Ward-Alexander L, Katz B: Cost-effectiveness of providing insurance benefits for post-hospital psychiatric halfway house stays. American Psychologist 45:1118-1126, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. DeLeon G: Residential therapeutic communities in the mainstream: diversity and issues. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 27:3-16, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. DeLeon G: Therapeutic communities for substance abuse: overview of approach and effectiveness. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 3:140-147, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Sturz EL: Dealing With Disruptive Adolescents and Drugs. New York, Argus Community, Inc, 1990Google Scholar

29. McLaughlin P, Pepper B: Modifying the therapeutic community for the mentally ill substance abuser. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 50:85-93, 1991Google Scholar

30. Zuckerman M, Sola S, Masterson J, et al: MMPI patterns in drug abusers before and after treatment in therapeutic communities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 43:286-296, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Van Putten T: Milieu therapy: contraindications? Archives of General Psychiatry 29:640-643, 1973Google Scholar

32. Islam A, Turner KL: The therapeutic community: a critical appraisal. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 143:467-472, 1982Google Scholar

33. McLellan AT: Psychiatric severity as a predictor of outcomes from substance abuse treatment, in Psychopathology and Addictive Disorders. Edited by Meyer RE. New York, Guilford, 1986Google Scholar

34. Gottheil E, McLellan AT, Druley KA: Reasonable and unreasonable standards in evaluation of substance abuse treatment, in Matching Patient Needs and Treatment Methods in Substance Abuse. Edited by Gottheil E, McLellan AT, Druley KA. New York, Pergamon, 1981Google Scholar

35. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, O'Brien CP, et al: An improved evaluation instrument for the substance abuse patient: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26-33, 1981Google Scholar

36. Radloff LS: The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1:365-401, 1977Google Scholar

37. Robinson JP, Shaver PR, Wrightsman LA: Measures of Personality and Social and Psychological Attitudes. New York, Academic Press, 1980Google Scholar

38. Dohrenwend BP, Levav I, Shrout PE: Screening scales for the Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Instrument (PERI), in Community Surveys of Psychiatric Disorder. Edited by Meyers JK, Ross C. New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers University Press, 1986Google Scholar

39. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799-812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

40. Endicott JE, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, et al: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766-771, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Moos RH: Community-Oriented Programs Environment Scale Manual, 2nd ed. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1983Google Scholar

42. Stata Corporation: State Reference Manual, Release 3.1, 6th ed. College Station, Tex, 1993Google Scholar

43. Hosmer KW, Lemeshow S: Applied Logistic Regression. New York, Wiley, 1989Google Scholar

44. Miller WR, Cooney NL: Designing studies to investigate client-treatment matching. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 12:38-45, 1994Google Scholar