Self-Help and Community Mental Health Agency Outcomes: A Recovery-Focused Randomized Controlled Trial

Consumer-operated programs are varied: they include drop-in centers, case management programs, outreach services, businesses, job search and training, housing, crisis services, and education and advocacy programs ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ). Typically organized as nonprofits, these programs are defined by the role of consumers, who serve as executive director, constitute at least 50% of the governing board, and may plan and provide services, offer mutual support to participants, and make decisions about how money is spent ( 5 ). These programs are thought to engage consumers who may be hesitant to seek traditional services.

The federal government has supported the development, evaluation, and financing of consumer-operated programs ( 6 , 7 ). State and local public mental health systems also support these programs, which are increasingly called on to coordinate their efforts with community mental health agencies (CMHAs) ( 7 , 8 ).

Until recently, most research on the effectiveness of consumer-operated programs has been cross-sectional in nature, limited by small samples, or otherwise compromised by lack of methodological rigor ( 9 , 10 ). Recent randomized controlled trials indicate mixed to modest positive outcomes favoring program participation. In one study, consumer-operated crisis residential services, compared with traditional mental health inpatient services, resulted in more rehospitalizations in the follow-up period but showed no difference in the length of stay and showed a modest positive initial but unsustained symptom improvement and higher satisfaction scores ( 11 ). In a second study, investigators found fewer hospital admissions, shorter hospital stays, and reduced symptomatology among participants in a consumer-operated program ( 12 ). In other studies, participants receiving joint consumer-operated and CMHA services had higher levels of subjective well-being ( 13 ) and personal empowerment than those receiving CMHA services alone, although overall effects were modest ( 9 ). Researchers speculate that different program types within and across studies may be related to observed differences in salutary outcomes ( 9 , 10 ).

Studies using consumer consensus have attempted to identify common or critical elements of consumer-operated programs in terms of program structure, environment, service elements, and values. One study found consumer control to be a key structural element, which encompasses consumer choice and decision making, consumer involvement in determining policies and procedures, nonhierarchical program structure, and respect for members ( 14 ). Another study found consumer involvement in hiring decisions, governance, and budget control to be among the core structural components ( 15 ). These studies, however, did not address the procedural elements of consumer control—specifically, the processes by which nonstaff and non-board members exert influence over organizational decisions.

Given empirically validated differences in their program environments, consumer-operated drop-in centers may be classified as either self-help agencies (SHAs)—programs run as participatory democracies where members can help make significant organizational decisions—or board-and staff-run programs where member decision making is confined to program content ( 16 ). Whereas the latter may provide services more efficiently, the former is structured to allow members wider opportunities for organizational decision making ( 17 ). In this study we looked at SHA multiservice centers that include a drop-in component, which is a model advocated in the consumer literature ( 18 ), to determine the effectiveness of the combined-service efforts of SHAs and CMHAs compared with CMHA services alone. We looked at outcomes that fit well within the recovery model framework—a framework endorsed by the mental health consumer movement and public mental health systems.

SHAs, like other consumer-operated programs, may be incorporated as nonprofit organizations and are managed and staffed by current patients, former patients, or both. They are run as participatory democracies emphasizing self-help through a community meeting process that allows members to vote on all aspects of the organization's operations, including the agency's budget, personnel issues, funding decisions, and planning. The SHA program theory is that individuals empowered to run their own helping organization will become more empowered in their own lives ( 18 ). The theory has received some empirical support; in a study of 254 individuals in 20 diverse consumer-operated programs, structural equation modeling showed that "there is a positive effect of an empowering participation experience on recovery …, suggesting that people who are more involved in the organizational operations of [the agency] tend to benefit more from participation ( 10 )." Also, in a study of 310 long-term users of four SHA drop-in centers, individuals who were more organizationally empowered at baseline were more likely to show greater gains in personal empowerment at a six-month follow-up ( 19 ).

SHA drop-in centers, in addition to promoting high levels of client participation in organizational decision making, provide social support, material assistance, and vocational opportunities ranging from volunteer roles to staff positions. They provide easy access to a nonthreatening environment and day shelter in a setting that requires minimal disclosure of personal information, allows the client to accept help at his or her own pace, makes no service dependent on the acceptance of another, and permits clients to pick and choose which services are appropriate for them ( 20 ).

CMHAs are frontline professional mental health treatment organizations serving individuals with serious mental illnesses. They operate as public agencies or as nonprofits under contract with public entities, and they provide inpatient and outpatient treatment, medication management, and case management services. Because studies have found little difference between consumer and professional case management efforts ( 21 ), cost-conscious mental health governing bodies are delegating socially based interventions to SHAs, leaving CMHAs to focus primarily on clinical interventions ( 22 ). This study assessed how this division of labor affects new clients who seek help from these organizations.

Recovery has been described as a personal journey that may involve developing hope, a secure base and sense of self, supportive relationships, social inclusion, empowerment, and increased control over one's symptoms ( 23 , 24 , 25 ). We hypothesized that combining SHA and CMHA services would improve client empowerment, social function, symptomatology, social inclusion, self-efficacy, and hope for recovery. The study sought to determine the contribution of combined services toward enhancing these recovery-focused outcomes.

Methods

The study design was a two-group randomized controlled trial at five SHA-CMHA program pairs serving the same geographic areas. SHA-CMHA pairs were chosen for their geographic proximity (median distance between sites was 2.5 miles). Agency pairs were often within walking distance of each other in urban settings and within a short ride in suburban or rural settings, allowing for successful referrals and comparisons of local SHA-CMHA service utilization.

Between 1996 and 2001 all new CMHA clients accepted for service under California medical necessity criteria (without private insurance, with a diagnosis covered by Medicaid, and with a significant impairment or probability of deterioration in an important area of life functioning) were invited by research staff to enroll in the study ( 26 ). Eighty-six percent (N=1,042) agreed to participate and provided their informed consent. Clients were then randomly assigned, at a ratio of approximately 1 to 4, respectively, to continued CMHA outpatient treatment or a combination of SHA-CMHA services. Service assignment was predetermined in a sealed envelope and unknown to the clinician or the researcher. After receiving the client's consent, the researcher opened the envelope, which revealed either that the client would receive services at the CMHA and also be asked to attend a self-help program or simply that he or she would receive services at the CMHA.

Interviews were conducted at baseline and at one, three, and eight months with 80% (N=834) successful follow-up. There were no crossovers to the SHA-CMHA sample from the CMHA-only sample. No significant differences in gender, race-ethnicity, and housing status were found between participants and those who refused participation. No differences were observed between those successfully followed and those not. All study procedures had institutional review board approval.

Participating agencies

On average, SHAs were open 5.3 days a week and served 43 clients a day. All had a consumer director and a governing board with a majority of consumer-members and allowed consumers the right to hire and fire staff.

The SHAs provided consumer-operated services guided by a self-help ideology. Common service elements included peer support groups, material resources, drop-in socialization, and direct services. The physical facilities varied from a large common room with a small number of meeting rooms and offices to more enhanced facilities, including a kitchen, dining area, and shower and locker areas. Services included help in obtaining survival resources (food, shelter, and clothing), money management, counseling, payeeship services, case management, peer counseling, and provision of information or referral. All SHAs provided physical space for socializing and developing ongoing peer support networks. They also offered opportunities for involvement in local, state, and national advocacy efforts ( 27 ).

An independent sample of 237 consumers self-referred to the SHAs at the same time as the study sample rated the organizational environments of the SHAs and the extent to which they were empowered by participation in the settings ( 16 ). After one month of service, the members of this sample indicated that these organizations emphasized the exchange of mutual support and practiced a high degree of participatory governance, with low scores on the staff control subscale of the Community-Oriented Programs Environment Scale ( 16 ).

CMHAs were county mental health organizations providing outpatient mental health services for people with serious mental illness who were believed to have characteristics similar to those of members of the paired SHAs. CMHA assistance included assessment, medication review, individual and group therapy, case management, and referral.

Assessment and measurement

Interview schedules included questions on demographic characteristics and recovery indicators as well as the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, version IV (DIS-IV). These were pretested with a sample of 310 long-term users of SHAs in northern California ( 19 ) and with 30 CMHA clients. Interviews were conducted by trained research staff at the Center for Self Help Research in Berkeley, California.

Member-clients were assessed on five recovery-focused outcome measures: empowerment of the individual in everyday life was assessed with the Personal Empowerment Scale ( 28 ); self-efficacy with the Self-Efficacy Scale ( 29 ); individual social integration—including social presence, access, participation, production (employment plus education involvement), and consumption behaviors—was measured with the Independent Social Integration Scale ( 30 , 31 ); psychological functioning was assessed with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) ( 32 ); and lack of hope was measured with the Hopelessness Scale ( 33 ). Higher scores on all scales indicate more of the named characteristic; for example, higher BPRS scores indicate greater severity of psychiatric symptoms. Scale alphas ranged from .83 to .95; stability scores, from r=.48 to .69 across a six-month period; and all scales possessed independently established validity ( 28 ). BPRS interrater reliability was maintained throughout the study at a minimum of .80 (according to repeated assessments of interviewers' ratings of filmed clinical interviews).

Analyses

Analyses were completed with SPSS, version 16.0 ( 34 ). Frequencies and means were computed for the sample's descriptive characteristics. Differences in individual characteristics between the SHA-CMHA and CMHA samples at baseline were evaluated by inspection to avoid redundant significance testing.

The SPSS general linear model (GLM) multivariate analysis of covariance for repeated measures was used to evaluate differences between groups and across time. Sample analyses were weighted by the inverse of the probability of reaching eight months of service in the client's assigned service or services. The referred SHA-CMHA sample was weighted by the inverse of the joint probability of completing eight months of service in both service agencies. The model assessed the impact of service condition (combined SHA-CMHA versus CMHA only) and program (the county program in which services were received) on five recovery outcome variables (noted above and measured at four points in time). Because of differences observed after the random assignment of the participants, demographic characteristics (reported below), including race (Caucasian versus other), gender, homelessness, and failure to complete high school, were included in the model. Also included was a propensity score accounting for self-selection into an SHA or a CMHA. The latter score was derived from analyses comparing the characteristics of new clients self-referring to the SHAs versus the CMHAs ( 35 ). Observed mean differences were considered significant at .05. The GLM repeated-measures model was evaluated without mean substitution.

Results

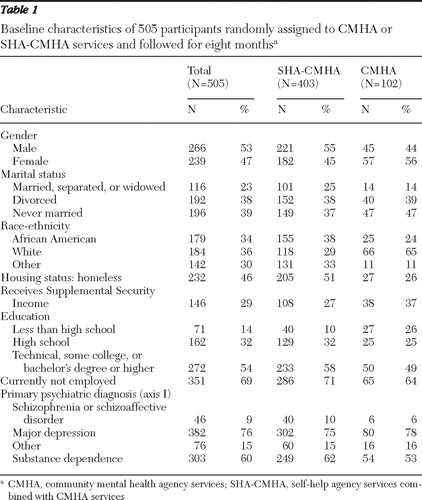

Of the 1,042 individuals in the weighted sample at baseline, 48% (N=505) continued using the services to eight months, including 51% (N=403) in the combined SHA-CMHA service condition and 46% (N=102) in the CMHA-only condition. No one in the latter group visited the SHA as a self-referral during the study. The mean±SD number of visits per month to the SHA was 6.50±9.34 (median=2; mode=2), and the mean number of visits to the CMHA was 3.21±2.72 (median=2; mode=1). Age was 41.0±7.8 in the SHA-CMHA sample and 38.0±10.0 in the CMHA sample. Of those followed up at eight months, 53% were men and 47% were women; 34% were African American, 36% were Caucasian, and 30% were of other racial-ethnic identities. A majority of the sample, 76%, had a DSM-IV diagnosis of major depression, as assessed with the DIS-IV ( Table 1 ).

|

Despite random assignment, some demographic differences were observed between the SHA-CMHA and CMHA conditions. Notably, fewer men, a greater proportion of Caucasians, fewer homeless persons, and fewer individuals who did not complete high school were assigned to the CMHA condition.

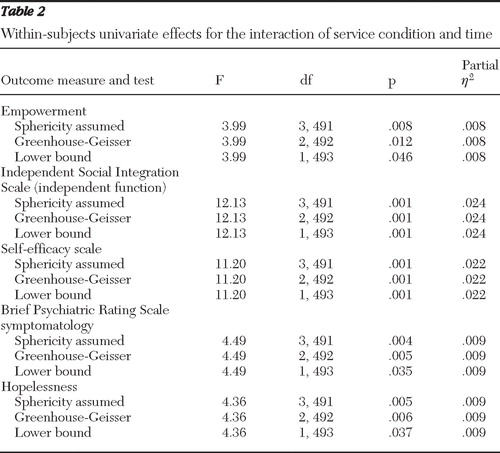

In a repeated-measures multivariate analysis of covariance, the overall results demonstrated that combined SHA-CMHA services were significantly better able to promote recovery of client-members than CMHA services alone. The results indicated that the two service condition groups changed significantly across time (service condition, Wilks' λ =.90, F=9.26, df=6 and 489, p<.001, η2 =.10; time, Wilks' λ =.71, F=10.63, df=18 and 477, p<.001, η2 =.29; and service condition × time interaction, Wilks' λ =.74, F=9.06, df=18 and 477, p<.001, η2 =.25). All of the five individually assessed outcomes showed significant change across time in interaction with service condition (see Table 2 ). The combined SHA-CMHA sample showed greater improvements in personal empowerment (F=3.99, df=3 and 491, p<.008), self-efficacy (F=11.20, df=3 and 491, p<.001), and independent social integration (F=12.13, df=3 and 491, p<.001). BPRS symptoms (F=4.49, df=3 and 491, p<.004) and hopelessness (F=4.36, df=3 and 491, p<.005) dissipated more quickly and to a greater extent in the combined-services condition than in the CMHA-only condition. [The marginal means derived from the model are presented in a figure available as an online supplement to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

|

The combined overall effect sizes measured by eta-squared were 10% of the variance for the service conditions, 29% for time, and 26% for the interaction of time with service condition. The individual outcomes for the interaction of time and service condition yielded eta-squared values in 1% to 2% of the variance range. Given recognized guidelines, the overall effect size can be characterized as medium to large (medium, 6% to 13.8%; large, <13.8%); the effect size for each of the individual outcomes was small (<6%) ( 36 , 37 ).

On the basis of the improvement shown in the BPRS, the difference in average improvement between the SHA-CMHA and CMHA conditions (the absolute risk reduction, or ARR) was 16.1%. The number of member-clients needed to engage in the combined condition in order to see a 16.1% improvement in one individual in BPRS scores was 6.2. Similarly, for independent social integration the ARR was 10% and the number needed to engage was 10.

Discussion

Combined SHA-CMHA services produced more positive results than CMHA services alone. Although the recovery process is nonlinear and is accompanied by both successes and failures, this study addressed the relative effectiveness of combined SHA-CMHA efforts in promoting recovery outcomes over time. Improvements were observed in many aspects of recovery, including increased personal empowerment, self-efficacy, and social integration and more rapid remission of psychological symptoms and hopelessness. The results further support the principle of using the empowering process of the SHA in enhancing positive outcomes.

The results pose significant challenges to public mental health systems regarding financing, policy development, and quality assurance of such approaches. Results also pose challenges to CMHAs that may have reservations about SHA involvement in providing mental health services and to the consumer movement itself. Although the study results represent the most positive outcomes attributable to such SHA-CMHA programs to date, they were derived from a select group of consumer-run agencies, SHAs that use participatory processes to empower their members. Though considerable knowledge exists on how to develop successful cooperative organizations in business and agriculture ( 38 , 39 ), the consumer movement acknowledges that consumer-operated mental health programs have met considerable challenges in implementing participatory processes ( 40 ). Although board- and staff-run programs may operate more efficiently by delegating major decision making to a consumer-led governing body, consumer-director, and consumer staff, their relative effectiveness in service provision remains an open question. This question has yet to be addressed in the consumer-operated program literature.

The strength of the study outcomes could still be improved. Although the overall effect size for improvement seemed very satisfactory in the medium-to-large range, all the effect sizes for the individual recovery measures across time were small. Also, although these findings are encouraging, they must be tempered by the fact that they gave weight to those staying with the program for the full eight-month period. Furthermore, although empowerment objectives seem to be important mediators of recovery, problems with symptomatology and social integration are the issues that bring people to mental health services and are what these services must address to claim success. Study results indicate that in order to see the type of enhanced improvement in BPRS symptoms for one individual through receiving combined services rather than CMHA services alone, six individuals needed to be served in the combined condition. To achieve observed improvement in independent social integration for one individual in the combined condition, ten individuals needed to be served. Local CMHAs need to determine whether allocating ever-diminishing resources to SHAs for complementary services is feasible, given the number of participants these SHAs (in collaboration with CMHAs) would have to serve in order to get marginal improvement over CMHA services alone for one client.

Conclusions

Study results generalize only to the universe of SHA-CMHA efforts in the San Francisco Bay Area approximately ten years ago. The study included a high proportion of enrollees with major depression ( 41 ). Consequently, positive results need replication with other general admission samples and with particular sociodemographic and diagnostic subgroups. Further investigations should document the linkage between the empowering process and participant outcomes. These results, however, within their limits, reflect most positively on the potential of the consumer-operated SHA as an integral part of the spectrum of mental health services and on successful SHA-CMHA collaboration in promoting recovery of people with serious mental illness.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by research grant RO1-MH-37310 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by the Mack Center on Mental Health and Social Conflict.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Long L, Van Tosh L: Program Descriptions of Consumer-Run Programs for Homeless People With Mental Illness. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1988Google Scholar

2. National Resource Center on Homelessness and Mental Illness: Self-Help Programs for People Who Are Homeless and Mentally Ill. Delmar, NY, Policy Research Associates, 1989Google Scholar

3. Van Tosh L, del Echo P: Consumer-Operated Self-Help Programs: A Technical Report. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, 2001Google Scholar

4. Campbell J: The historical and philosophical development of peer-run support programs; in On Our Own, Together. Edited by Clay S. Nashville, Tenn, Vanderbilt University Press, 2005Google Scholar

5. Goldstrom I, Campbell J, Rogers J, et al: National estimates for mental health mutual support groups, self-help organizations, and consumer-operated services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 33:92–103, 2006Google Scholar

6. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 1999Google Scholar

7. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003. Available at www.mentalhealthcommission.gov/reports/reports.htm Google Scholar

8. Proposition 63: the Mental Health Services Act. Available at www.dmh.ca.gov/prop_63/MHSA/default.asp Google Scholar

9. Rogers ES, Teague GB, Lichenstein C, et al: Effects of participation in consumer-operated service programs on both personal and organizationally mediated empowerment: results of multisite study. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development 44:785–800, 2007Google Scholar

10. Brown LD, Shepherd MD, Merkle EC, et al: Understanding how participation in a consumer-run organization relates to recovery. American Journal of Community Psychology 42:167–178, 2008Google Scholar

11. Greenfield T, Stoneking BC, Humphreys K, et al: Randomized trial of a mental health consumer-managed alternative to civil commitment for acute psychiatric crisis. American Journal of Community Psychology 42:135–144, 2008Google Scholar

12. Dumont J, Jones K: Findings from a consumer/survivor defined alternative to psychiatric hospitalization. Outlook 3:4–6, 2002Google Scholar

13. Campbell J: Effectiveness Findings of a Large Multi-Site Study of Consumer-Operated Services (1998–2006). University of Illinois, Department of Psychiatry, 2009. Available at www.psych.uic.edu/uicnrtc/nrtc4.webcast1.jcampbell.slides.pdf Google Scholar

14. Holter MC, Mowbray CT, Bellamy CD, et al: Critical ingredients of consumer run services: results of a national survey. Community Mental Health Journal 40:47–63, 2004Google Scholar

15. Johnsen M, Teague G, Herr EM: Common ingredients as a fidelity measure; in On Our Own, Together. Edited by Clay S. Nashville, Tenn, Vanderbilt University Press, 2005Google Scholar

16. Segal SP, Silverman C, Temkin T: Assessing Consumer-Operated and Self-Help Agency Program Environments. Berkeley, Calif, Mental Health and Social Welfare Research Group, 2010Google Scholar

17. Chamberlin J: Direct democracy as a form of program governance; in Reaching Across II: Maintaining Our Roots/The Challenge of Growth. Edited by Harp HT, Zinman S. Sacramento, California Network of Mental Health Clients, 1994Google Scholar

18. Zinman S, Harp HT, Budd S (eds): Reaching Across, Mental Health Clients Helping Each Other. Riverside, California Network of Mental Health Clients, 1987Google Scholar

19. Segal SP, Silverman C, Temkin T: Characteristics and service use of long-term members of self-help agencies for mental health clients. Psychiatric Services 46:269–274, 1995Google Scholar

20. Segal SP, Baumohl J: The community living room. Social Casework 66:111–116, 1985Google Scholar

21. Solomon P, Draine J: The efficacy of a consumer case management team: 2-year outcomes of a randomized trial. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:135–146, 1995Google Scholar

22. Allness D, Knoedler W: The PACT Model of Community-based Treatment for Persons With Severe and Persistent Mental Illnesses: A Manual for PACT Start-up. Arlington, Va, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 1998Google Scholar

23. National Consensus Statement on Mental Health Recovery: 2004. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, 2004. Available at download.ncadi.samhsa.gov/ken/pdf/SMA05-4129/trifold.pdf Google Scholar

24. Ramon S, Healy B, Renouf N: Recovery from mental illness as an emergent concept and practice in Australia and the UK. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 53:108–122, 2007Google Scholar

25. Bellack AS: Scientific and consumer models of recovery in schizophrenia: concordance, contrasts, and implications. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:432–442, 2006Google Scholar

26. Title 9. California Code of Regulations, Chapter 11.1830.205 Medical Necessity Criteria for Specialty Mental Health Services. Available at www.dmh.cahwnet.gov/DMHDocs/docs/letters01/01-01_enclosure1.pdf Google Scholar

27. Chamberlin J: The ex-patient's movement: where we've been and where we're going. Journal of Mind and Behavior 11:323–336, 1990Google Scholar

28. Segal SP, Silverman C, Temkin T: Measuring empowerment in client-run self-help agencies. Community Mental Health Journal 31:215–227, 1995Google Scholar

29. Bandura A: Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review 84:191–215, 1977Google Scholar

30. Segal SP, Aviram U: The Mentally Ill in Community-Based Sheltered Care. New York, Wiley, 1978Google Scholar

31. Segal SP, Kotler PL: Personal outcomes and sheltered care residence: ten years later. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 63:80–91, 1993Google Scholar

32. Overall J, Gorham D: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799–812, 1962Google Scholar

33. Zimmerman MA: Toward a theory of learned hopefulness: a structural model analysis of participation and empowerment. Journal of Research in Personality 24:71–86, 1990Google Scholar

34. SPSS 16.0 for Windows. Chicago, SPSS Inc, 2009Google Scholar

35. Segal SP, Hardiman ER, Hodges JQ: Characteristics of new clients at self-help and community mental health agencies located in geographic proximity. Psychiatric Services 53:1145–1152, 2002Google Scholar

36. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1988Google Scholar

37. Pallant JF: SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis, 3rd ed., rev. New York, Allen & Unwin, 2007Google Scholar

38. What's a Co-op? Petaluma, Calif, Alverado Street Bakery. Available at www.alvaradostreetbakery.com/coop.html Google Scholar

39. Starting a Co-op. Davis, University of California, Davis, Rural Cooperatives Center. Available at www.cooperatives.ucdavis.edu/starting/index.htm Google Scholar

40. Zinman S: Issues of power; in Reaching Across, Mental Health Clients Helping Each Other. Edited by Zinman S, Harp HT, Budd S. Riverside, California Network of Mental Health Clients, 1987Google Scholar

41. Kashner TM, Rush AJ, Surís A, et al: Impact of structured clinical interviews on physicians' practices in community mental health settings Psychiatric Services 54:712–718, 2003Google Scholar