Co-occurring Disorders and Learning Difficulties: Client Perspectives From Two Community-Based Programs

The combination of learning disabilities and mental illness is a social problem in the United States. Using 2004 U.S. Census data, the National Institute of Mental Health estimated that 57.7 million people (26%) in this country have a mental disorder ( 1 ). Although it is difficult to estimate the number of adults with learning disabilities, the prevalence of learning disabilities among school-age children is approximately 6% of the total student population and about half of all students in special education ( 2 ). However, prevalence rates of learning disabilities among adolescents in mental health treatment programs have ranged from 40% to 70% ( 3 ) and to as high as 80% among adolescents in a shelter ( 4 ). The National Institute for Literacy estimates that 40% to 50% of people in social service programs have a learning disability ( 5 ).

Despite overrepresentation of people with learning disabilities in social service agencies and mental health treatment programs, the needs of adults with learning disabilities are often overlooked. Although there has been a focus on learning disabilities as a problem of childhood and adolescence, recent research findings suggest that learning disabilities continue to have an impact on work, education, and independent living skills throughout adulthood ( 6 ). Adults have reported that a number of areas of functioning are affected by their learning disability ( 7 ). People with a learning disability who also have a mental illness or a substance use disorder or both present a challenging co-occurring diagnosis profile that needs further study.

This exploratory study examined the experience of adults in the mental health system with possible learning disabilities and co-occurring disorders of mental illness and substance abuse. Qualitative interviews focused on six areas of functioning that, on the basis of previous research ( 8 ), may be affected by learning disabilities.

Methods

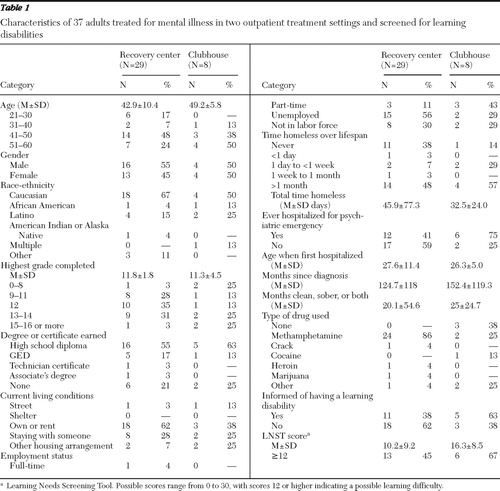

The sample was obtained through criteria sampling after institutional review board approval. Clients from two county social service agencies providing outpatient treatment—a dual-diagnosis recovery center and a clubhouse—constituted the study population. Data collection for this study began in October 2007 and continued through February 2008. Clients at each agency voluntarily listened to the study announcement. Most clients attending treatment on the day of the study agreed to participate in it and provided written consent. They were then given two instruments to determine whether they may have learning difficulties: a background questionnaire, which was a 19-item instrument that included demographic and social characteristics, and the Learning Needs Screening Tool (LNST) ( 9 ). The LNST is a 14-item screening tool standardized in social service settings and includes a subset of questions most predictive in determining learning disabilities ( 10 ). The term "learning difficulties" rather than "learning disability" will be used to reference participant outcomes on the LNST. The study did not exclude any clients from participating.

Participants who scored 12 or higher (out of a possible 30 points) on the LNST were considered to have a possible learning difficulty and were asked to participate in a semistructured, audiotaped interview. The interview was designed to gather information about participants' experiences regarding education, relationships, vocation, housing, mental health, and access to social services. The recordings were transcribed and then coded by the researcher and an independent reviewer to elicit macro-level themes (representing broad categories of experiences) and subthemes.

Results

Results from the Background Questionnaire and the LNST were obtained for 37 participants (29 at the recovery center, eight at the clubhouse) and are presented in Table 1 . Nineteen participants scored 12 or higher on the LNST and were considered to have a possible learning difficulty, and nine of this group agreed to be interviewed. Among the 19 who met criteria, analyses revealed no significant differences between those who were interviewed and those who were not. Interview participants (six from the recovery center and three from the clubhouse) had an average age in the mid-40s (M±SD=43.9±8.4) and included individuals identifying as Caucasian, Latino, African American, and being of mixed race. Less than half of interview participants had a high school diploma (N=4, 44%). Most participants owned or rented a house or apartment (N=5, 56%). Seven out of nine (78%) interview participants were not working, and three (33%) reported lifetime homelessness averaging over 1.5 months (45.9±77.3 days).

|

Seven of nine interview participants (78%) had been hospitalized for a psychiatric emergency, typically when in their late 20s (M±SD age=28±10). Participants described having a diagnosis of mental illness for an average of over 13 years (158±127 months). Methamphetamine was the clear drug of choice among interview participants (N=7, 78%). Additional diagnostic information was unavailable, but both agencies provide services to people with serious mental illness.

Eight out of nine participants had been told that they had a learning disability. One participant knew she had a learning disability because of frustration when reading but attended school before 1974, when Public Law 94-142 mandated school interventions for students with learning disabilities. The LNST verified data reported by interview participants. The average score on the LNST in this subsample was 20.8±5.2.

Macro-level themes of education, relationships, vocation, housing, mental health, and social services were explored in the interviews. Education included the subtheme of frustration in school. All participants reported that they experienced frustration and obstacles because of their learning disability. Client J: "Hard, frustrated, I just felt a lot of anger because I couldn't understand. … I didn't feel good about myself. … I thought that people were just downgrading at me." Feeling different was reported in eight of the interviews as participants discussed how they viewed themselves, often in comparison with peers without learning difficulties. Client P: "It's frustrating … you feel less than." Dropping out of school was reported by five of nine participants. Client J: "I didn't have to worry about people looking at me, laughing at me, or teasing me." Reading strategies were noted as participants considered their educational experience and their adult experience with learning difficulties. Client P: "I can't retain stuff very well if I'm reading them. But if someone reads to me or shows me something, I pick it up right away." Reflecting on educational goals, Client J stated, "I want to get back on some computers and learn the basics, learn how to read and pronounce some words and stuff."

Relationships represented both support and stress. The relationships cited involved parents, friends, spouses, ex-spouses, children, special education teachers, and therapeutic relationships. All nine participants identified lack of intimacy and lack of trust in others that often began in early relationships with family and peers and continued into adult relationships. Client J: "The more you let a person know about you, the more that they have against you to destroy you." Five participants identified the impact of a relationship with a special education teacher, stating roles such as "miracle worker" and "giving attention." Five expressed relationships broadly as a desire to be a responsible parent. Client J: "I figured that I would try and help myself; then I would be able to help them."

Vocational issues were reported by six participants as they described their extensive history of job instability. Client J: "I didn't have a job until I got out of the prison." Eight participants noted job skill preference. Client P: "I've always done sales, because I was good at selling drugs, too." Four participants described ways in which a learning difficulty affects job performance, such as the need to be able to read a menu in a job. Client J: "I was getting frustrated because it reads it on there and my reading isn't that good."

Housing instability was reported by all participants who struggled to maintain stable housing throughout life, and all had experienced periods of homelessness, which ranged from, "I slept in the streets" to "sleeping on other people's couches." Obstacles to housing included money, work, mental illness, and education.

Mental health referred to issues of mental illness, which was an admissions requirement for clients at the recovery center and the clubhouse. Seven participants identified low self-esteem and attributed its cause to mental illness, learning difficulties, or both. Client B: "I think when you have a difficulty, it lowers your self-esteem. … I don't know if it brings on the mental [illness] and more intensifies it." Seven participants described their level of understanding about the impact of having a learning disability as ranging from "beginning to question" what it has meant to being able to state specific impacts, such as challenges with reading in adulthood. Client P: "I get mad sometimes; I wish I did not have to ask somebody, 'What is this word and what is the definition of it?'"

Social services issues concerned participant interaction with the system. Paperwork at social service agencies was seen by eight participants as an obstacle to obtaining supporting documents. Client P: "I don't fill it out. … I just get mad and leave." Five participants discussed limited public transportation, which connected participants to housing, social services, jobs, and family. Client J: "I didn't want to go back to my furniture job because I didn't have no transportation and it required transportation." Suggestions for improvement in service delivery to meet clients' learning needs included technology innovations, early identification of learning disabilities, and reading material at low comprehension level. Client P: "For those that couldn't read, they should have audios."

Discussion

Adults with possible learning difficulties in combination with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders seek treatment in mental health agencies, creating a service delivery gap that ignores the obstacles of having a learning difficulty while navigating the mental health system. Significant prevalence rates of learning difficulties among people in the social service programs studied demonstrate a need for intervention. Participants described how their learning difficulties affected their education, relationships, housing, and mental health and served as a major barrier in accessing social services. Addressing learning needs at the agency and direct service levels may facilitate identification and intervention. Partnerships between mental health agencies and literacy centers could increase appropriate referrals.

The findings of this study of adults support the long-term impact of emotional challenges faced by children and adolescents with learning disabilities. Although our sample was small, the results from this study also support a lifespan approach to understanding how a learning disability affects people in the mental health system. The lifespan approach hypothesizes that those with a learning disability struggle in school and then leave the education system and struggle with employment, housing, relationships, and mental health before or concurrent with seeking treatment ( 11 ).

Generalizability of findings is limited because of this study's small sample. Themes common to participants interviewed at the two mental health agencies may not represent those of a larger treatment population, and participation may differ at each agency on a particular day. No interviews were conducted with those who did not meet criteria for possible learning difficulties. It is beyond the scope of this exploratory study to determine causality or the relationship of learning problems and mental health problems. Age, education, time homeless, age at first hospitalization, LNST score, years since first diagnosis, and months of sobriety were compared; only the LNST score was significantly different between the group interviewed and all others who were screened, suggesting that the groups were roughly similar demographically and clinically.

Conclusions

Participants with a learning disability began mental health treatment with a lifetime of experiences—beginning with school experiences—that represented frustration, embarrassment, and feeling different because of their learning challenges, all of which created an emotional overlay that has continued throughout their lives. Understanding the impact of learning disabilities on a client's life experience enhances the mental health providers' conceptualization of the person in treatment and creates opportunities for more comprehensive interventions.

This study continues the shift of the "learning disabilities" paradigm from a childhood problem toward a lifespan developmental perspective and begins to reveal the experience of adults with learning disabilities and co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders in the mental health setting. Future research should include mixed-methods longitudinal studies with large representative samples engaged in various treatment programs. Future studies examining the impact of substance use and learning difficulties could examine causality. This would contribute to the growing body of knowledge regarding adults with learning disabilities and mental illness through a lifespan perspective.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Statistics. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 2008. Available at www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics . Acessed Feb 2, 2008 Google Scholar

2. To Assure the Free Appropriate Public Education of All Children With Disabilities: 23rd Annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act. Washington, DC, US Department of Education, 2002Google Scholar

3. Yu JW, Buka SL, Fitzmaurice GM, et al: Treatment outcomes for substance abuse among adolescents with learning disorders. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 33:275–286, 2006Google Scholar

4. Barwick M, Siegal L: Learning difficulties in adolescent clients of a shelter for runaway and homeless street youths. Journal of Research on Adolescence 6:649–670, 1996Google Scholar

5. Bridges to Practice. Washington, DC, National Institute for Literacy, 2008. Available at www.nifl.gov/nifl/ld/bridges/bridges.html . Accessed Jan 18, 2008 Google Scholar

6. Mellard DF, Lancaster PE: Incorporating adult community services in students' transition planning. Remedial and Special Education 24:359–368, 2003Google Scholar

7. Roffman AJ: Meeting the Challenge of Learning Disabilities in Adulthood. Baltimore, Brookes, 2000Google Scholar

8. Markos P, Strawser S: The relationship between learning disabilities and homelessness in adults. Guidance and Counseling 19(2):46–56, 2004Google Scholar

9. Payne N: Learning Needs Screening Tool. Olympia, Wash, Payne & Associates, 2007. Available at www.ncwd-youth.info/assets/guides/assessment/sample_forms/learning_needs_screening_tool_word.doc . Acessed June 7, 2007 Google Scholar

10. Giovengo M, Moore EJ (eds): Washington State Division of Social Services Learning Disabilities Initiative: Final Report. Olympia, Wash, Department of Social and Health Services Economic Services Administration, Workfirst Division, 1998Google Scholar

11. Gerber PJ: Researching adults with learning disabilities from an adult-development perspective. Journal of Learning Disabilities 27(1):6–9, 1994Google Scholar