Criminal Justice Involvement of Armed Forces Veterans in Two Systems of Care

Increasing concern regarding the mental health and substance abuse treatment needs of armed forces veterans has spurred discussion of services provided to veterans outside the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) ( 1 ). A growing body of research has added to our understanding of veterans' choice of service system ( 2 , 3 ). However, few studies have compared the outcomes of services provided to veterans by VHA programs with the outcomes of services provided by other community-based programs. The study reported here addressed that area of concern by comparing rates of criminal justice involvement of two groups: VHA service recipients and veterans receiving services from the Department of Mental Health (DMH) in the same state.

Criminal justice involvement is one of the ten national outcome measures established by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and has been identified by major advocacy groups as a core measure of community program performance ( 4 ).

Criminal justice involvement of behavioral health service recipients has been the focus of substantial research, although research has tended to focus on either the VHA ( 5 ) or other public behavioral health systems of care ( 6 ). Research has also compared rates of incarceration for veterans and nonveterans ( 7 ). This study adds to previous research by comparing rates of criminal justice involvement for veterans in two systems of community-based care in the same state during the same period.

Methods

This study relied exclusively on analysis of anonymous extracts from databases maintained by the Vermont DMH, VHA, and the Vermont Center for Justice Research. All three data sets include date of birth, gender, and county of residence. The DMH and VHA databases include information regarding veterans who received community-based behavioral health services during 2007. Veterans with traumatic brain injury and other general medical diagnoses were not excluded from the study. The Center for Justice Research data include the type of crime for all individuals charged in a Vermont district court during 2006 and 2008. Because the data extracts used in the analysis were anonymous and the data sets did not share a common system for identifying unique persons, probabilistic population estimation ( 8 ) was used to provide valid and reliable estimates of the unduplicated number of people represented in the behavioral health treatment data sets who were also represented in the criminal charging data set. This approach is particularly useful where concerns about the confidentiality of medical records limit the use of person-identifying information ( 9 ).

Rates of criminal charging reflect the percentage of all veterans served who were charged during the specified period (before or after receipt of services). A simple pre-post measure of the rate of criminal charging was calculated by dividing the 2008 charge rate by the 2006 charge rate. The results were converted to a rate of change by subtracting 1 and expressing this rate of change as a percentage. A rate of change significantly less than zero indicates a significant decrease in criminal charging, and a rate significantly greater than zero indicates a significant increase.

The White River Junction Veterans Affairs Medical Center-Dartmouth Medical School Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this research. The Vermont Agency of Human Services IRB found that this research qualified for exemption from review.

Results

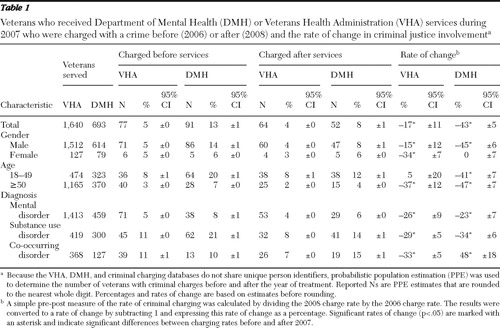

Participants included 1,640 veterans who received outpatient behavioral health services during 2007 from a VHA program and 693 people who were identified as veterans by the DMH program from which they received services ( Table 1 ). Probabilistic population estimation of caseload overlap indicated that only 64 of these veterans were served by both sectors during the study period; these individuals were included in both service sectors. Ninety-two percent of VHA service recipients and 89% of DMH service recipients were male. Seventy-one percent of VHA recipients and 53% of DMH recipients were at least 50 years old. More than two-thirds of veterans in both groups received services for mental disorders, and less than half in each group received services for substance use disorders. Individuals with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders represented less than 25% of each group.

|

VHA and DMH recipients both experienced significant decreases in criminal charging after receiving services. This overall positive outcome, however, was not experienced equally by VHA and DMH veterans or by veterans in different demographic and clinical categories ( Table 1 ). During the study period, criminal charging rates for VHA veterans decreased by 17%, from 5% during the year before the treatment year to 4% during the year after, whereas criminal charging rates for DMH veterans decreased by 43%, from 13% to 8%.

Male veterans receiving DMH services experienced a 45% reduction in criminal charging, and female veterans experienced no change. Among VHA service recipients, male veterans experienced a 15% reduction in criminal charging, and female veterans experienced a 34% reduction. In the DMH system, young veterans and older veterans experienced similar reductions in criminal justice involvement (41% and 47%, respectively). In the VHA system, however, older veterans experienced a substantial decrease in criminal justice involvement (37%), whereas younger veterans did not experience significant change (5%).

Criminal justice outcomes for service recipients with co-occurring disorders were very different in the two systems of care. These veterans experienced a 33% decrease in criminal charging in the VHA system and a 48% increase in the DMH system. Criminal charging rates for veterans with mental disorders decreased by 26% in the VHA system and by 23% in the DMH system; the respective decreases in rates for those with substance use disorders were 29% and 34%.

Discussion

This study found significant differences between the VHA and DMH service sectors in one northeastern state with regard to change in veterans' criminal justice involvement in the years before and after a year during which they received community-based behavioral health services. These differences may be related to differences in the individuals who choose to participate in one or the other system of care, to differences in the culture of the two organizations, or to the interaction of personal, demographic, and organizational factors.

It is important to note that this research focused on veterans who reside in one predominately white, rural New England state. These findings may not apply to urban areas, to more ethnically diverse areas, or to other regions. For this reason, it is important to conduct similar studies in geographical areas with other cultural characteristics. Similarly, this research focused on only one of many important treatment outcomes. Differences between systems of care with regard to outcomes such as rates of hospitalization, employment, homelessness, and other core measures of service system performance should be explored. Finally, this research focused on two important service sectors (VHA and DMH) but provided no information on veterans' use of private-sector community-based behavioral health services.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that there are important differences in the performance of these two community-based behavioral health service delivery systems with regard to the criminal justice involvement of service recipients. These differences and other potential differences in treatment outcomes should be considered in plans to provide behavioral health care to veterans, both within and outside the VHA system of care. Expansion of behavioral health services to veterans should be based on evidence regarding the strengths of each service sector. This evidence base should inform decisions at both the client level and the service sector level so that systems of care can work together both intelligently and collaboratively.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported in part by Data Infrastructure Grant 1HR1SM058069-03 from the Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The contents of this brief report are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of SAMHSA's Center for Mental Health Services. The authors express their appreciation to Charles D. Allard of the Vermont VA Medical Center and Joan M. Owen, B.S., of the Vermont Center for Justice Research for providing the data sets used in this analysis.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Burnham MA, Meredith LS, Tanielian T, et al: Mental health care for Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans. Health Affairs 28:771–782, 2009Google Scholar

2. Gamache G, Rosenheck RA, Tessler R: Factors predicting choice of provider among homeless veterans with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 51:1024–1028, 2000Google Scholar

3. Carey K, Montez-Rath ME, Rosen AK, et al: Use of VA and Medicaid services by dually eligible veterans with psychiatric problems. Health Services Research 43:1164–1183, 2008Google Scholar

4. Principles of Managed Care. Arlington, Va, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 1995Google Scholar

5. Erickson SK, Rosenheck RA, Trestmen RL, et al: Risk of incarceration between cohorts of veterans with and without mental illness discharged from inpatient units. Psychiatric Services 59:178–183, 2008Google Scholar

6. Pandiani JA, Banks SM, Schacht LM: Using incarceration rates to measure mental health program performance. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 25:300–311, 1998Google Scholar

7. Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA, Desai RA: Risk of incarceration among male veterans and nonveterans. Armed Forces and Society 33:337–350, 2007Google Scholar

8. Banks SM, Pandiani JA: Probabilistic population estimation of the size and overlap of data sets based on date of birth. Statistics in Medicine 20:1421–1430, 2001Google Scholar

9. Pandiani JA, Banks SM, Schacht LM: Personal privacy versus public accountability: a technological solution to an ethical dilemma. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 25:456–463, 1998Google Scholar