Trends in Recognition of and Service Use for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Britain, 1999–2004

Although attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common childhood disorder, epidemiological research suggests that most children with ADHD in Britain have not been identified or treated ( 1 ). British practitioners have traditionally used the narrower category of hyperkinetic disorder, which requires the presence of hyperactive, impulsive, and inattentive symptoms, and British psychiatrists have tended to be less likely than American psychiatrists to diagnose hyperactivity disorders when assessing the same children ( 2 ).

There is increasing evidence that childhood ADHD persists into adolescence and adulthood and is associated with a range of adverse outcomes, including other psychiatric disorders, poor academic attainment, and impaired social adjustment ( 3 ). Appropriate identification and treatment of affected children might reduce their long-term risks. However, any increases in the identification and diagnosis of children with ADHD will have implications for clinical services. National British data from 1999 indicated that less than one-third of children with ADHD had been seen by specialist health services ( 1 ). Data indicated that few parents of children with ADHD had consulted primary health care services, and parental factors, such as recognition of problems and perceived burden, were the main determinants of service use ( 1 ).

Policy and research developments in recent years might have altered this situation, by advocating for an increase in the availability of services and highlighting the added value of using medication for children with ADHD, particularly when symptoms are severe. These developments include the dissemination of findings from a large-scale trial of treatments for ADHD, national clinical guidance on the use of methylphenidate, and the availability of long-acting medications for ADHD ( 4 , 5 ). Although medication use for ADHD has increased globally ( 6 ), few nationally representative studies have investigated the service use patterns of children who meet criteria for ADHD ( 1 , 7 , 8 ). Population-based comparisons across time points enable the investigation of changes in rates and correlates of service use and provide useful data for service planners.

By operationalizing the stages of service use employed in our previous study ( 1 ) and using comparable national British data collected in 2004, we investigated changes in recognition and service use for ADHD over a five-year period (1999–2004). Using the cross-sectional 2004 data, we also examined predictors of parental recognition of problems and the use of various services. On the basis of earlier work ( 1 ), we expected that parental rather than child factors would be associated with service use.

Methods

Sample

The 2004 British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey. Data from the 2004 British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey (B-CAMHS) were used. It had a nationally representative sample of 7,977 children aged five to 16 who were identified through child benefit records (76% response rate). The sampling methodology was similar to that used in the 1999 survey, and details of recruitment and representativeness have been reported elsewhere ( 9 , 10 , 11 ). Diagnostic information in both surveys was based on the reliable and well-validated Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA) package that included a teacher questionnaire and a structured interview with the parent and child (if age 11 or older) that was administered by trained lay interviewers, who also recorded verbatim accounts of reported problems ( 10 , 12 ). Participants provided written informed consent. Most families (94%) gave permission to contact teachers, and teachers provided information for 83% of children.

To emulate the clinical diagnostic process as closely as possible, experienced clinicians reviewed all the available information and assigned diagnoses of ADHD using DSM-IV criteria ( 13 ) and hyperkinetic disorder using ICD-10 criteria ( 14 ). When relevant, they also took medication information into account to ensure that children receiving treatment for ADHD were given a research diagnosis of ADHD if appropriate. For this study, we focused on the 176 children who met criteria for ADHD (weighted prevalence rate of 2.2%). In keeping with British clinical guidelines ( 15 ), we did not exclude children who also met criteria for an autistic spectrum disorder (N=18). Ethical approval for the clinical rating and secondary analysis of these data was obtained from local and multicenter research ethics committees.

The 1999 British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey. This different sample of children aged five to 15 with ADHD (N=238) was identified by using a methodology similar to that used for the 2004 survey, which has been described elsewhere ( 1 ). To ensure equivalent samples in comparative analyses across the two periods, we also included children who met criteria for both ADHD and an autistic spectrum disorder (N=6).

Measures

Outcome measures. We report three main outcomes. First, before the DAWBA interview was carried out, we assessed parental recognition of problems. Parents were asked whether they thought that their child had any of the following current problems: hyperactivity, behavioral problems, emotional problems, learning difficulties, and dyslexia. Second, parents were asked whether they or their child had been in contact over the past year with professionals (such as teachers, professionals in specialist education services, primary health care providers, specialist health care providers, social workers, or others) about concerns relating to emotions, behavior, or concentration. Parents could indicate all applicable services.

We focused on contact with education-based professionals (teachers, educational psychologists, and school counselors), primary health care providers (general practitioners and nurses), and specialist health care providers (in pediatric services or child or adult mental health services). Clinical practice guidelines recommend that only specialist health care services should carry out diagnostic assessments and initiate medication for ADHD ( 5 , 15 ). In the 1999 survey, service use information reflected lifetime contact with services. Third, information about medication use was elicited by showing parents a list of commonly used psychoactive drugs with both nonproprietary and brand names.

Predictor measures. Sociodemographic measures included child gender, child age, living in a single-parent family, and house ownership. Parents rated their child's general health on a 5-point scale: very good, good, fair, bad, or very bad. This item, which was developed for these surveys, was dichotomized for analyses as good and very good versus fair, bad, and very bad health. Parental recognition of problems (as defined above) was examined as a predictor of service use. The General Health Questionnaire, a well-validated 12-item self-report questionnaire with established psychometric properties, was used to measure parental mental health ( 16 ). Each item is scored 0 or 1, and the B-CAMHS used a cutoff score of ≥3 as an indicator of screening positive for emotional disorder. This cutoff has high sensitivity and specificity for common psychological disorders.

Clinical measures were taken from the DAWBA. Severe ADHD was indicated if the child met criteria for hyperkinetic disorder; clinical guidelines in Britain have conceptualized hyperkinetic disorder as "severe ADHD" ( 15 ). Compared with children with ADHD, children who also meet criteria for hyperkinetic disorder have more severe symptoms and impairment in academic and cognitive functioning and have a greater response to medication treatment ( 17 ). Comorbidity reflected the presence of a comorbid anxiety, depressive, or oppositional-conduct disorder ( 14 ). To assess parent and teacher ratings of hyperactivity-related burden, informants were asked whether the difficulties placed a burden on them or the family or class (if relevant) on a 4-item scale: not at all, only a little, quite a lot, and a great deal. This measure of burden is specific to hyperactivity-related symptoms. The wording is the same as the burden item in the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire ( 18 ). The rating correlates well (r=.74) with the Child and Adolescent Impact Assessment, which is a standardized interview rating of the impact of the difficulties on the caregiver ( 18 , 19 ).

Analyses

For the 2004 ADHD sample, we carried out three main sets of comparisons: between parents who did and did not recognize a problem, between children who had used particular types of services and those who had not, and between children who did and did not receive medication. Previous analyses of data from these surveys have shown that weights are not necessary to investigate risk ( 9 ). Therefore, we used unweighted data, which reflect the sample of 176 children with ADHD.

The number and choice of predictor measures for specific outcomes reflected the sample size for each comparison and findings reported in the literature ( 1 , 8 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ). For the outcome of parental recognition of problems, on the basis of the literature ( 1 , 20 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 26 ), we examined the predictive roles of gender and age of the child, severity of the disorder, comorbidity, parental mental health, marital and housing status (as markers of socioeconomic status), and adult-reported burden. For the service use and medication outcomes, on the basis of the literature ( 1 , 8 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ), we examined the predictive roles of severity of ADHD, comorbidity, parental mental health, parental recognition of problems, and adult-reported burden. The main differences in the choice of predictor measures for service use reflected the possible roles of teacher-reported burden for contact with education and the child's general health for contact with health services.

We initially examined the univariable relationships between predictor and outcomes measures using logistic regression analyses to provide odds ratio (OR) estimates. Predictors with an association (p<.05) were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model to provide adjusted ORs.

To compare the ADHD samples from 1999 and 2004, before we combined the two data sets, ten 16-year-olds were excluded from the 2004 sample to ensure equivalent samples (five- to 15-year-olds) in comparative analyses. First, to investigate statistical changes in correlates of service use over time, we assessed for interactions between the sample (1999 or 2004) and individual predictors, and we report any associations (p<.05). The samples from 1999 and 2004 were then compared by using logistic regression analyses to provide OR estimates. Finally, multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to investigate the roles of year, severity of ADHD, parental recognition that the child has hyperactivity, and parental burden as predictors of specialist service use.

Results

Data for the 2004 sample characteristics are presented in Table 1 . Parents varied in their use of explanatory terms for their child's symptoms. Most parents (N=153, 87%) reported that they or their child had contacted at least one service in the previous year about concerns relating to emotions, behavior, or concentration: 130 (74%), education-based professionals; 90 (51%), specialist health services; 69 (39%), primary health care; and 29 (17%), social services.

|

Parental recognition of problems

In Table 2 the relationship between parental recognition of problems and the potential predictors is examined. Of the four predictors in the univariable analysis, only comorbidity was associated with parental recognition of problems in the multivariable logistic regression (OR=4.27, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.16–15.75, p=.029).

|

Contact with education-based professionals

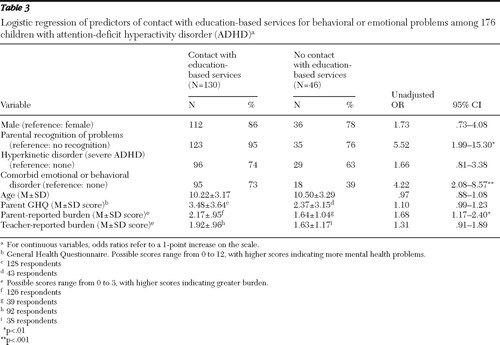

Most contacts with education-based professionals (92%, 119 of the 130 parents who reported contacts with this group) involved teachers. Table 3 presents findings from the analysis of predictors of contact with education-based professionals for behavioral or emotional problems. Only one of the four predictors remained significant in the multivariable logistic regression; comorbidity was associated with a greater likelihood of contacts (OR=2.71, CI=1.20–6.09, p=.016). Analyses of any interactions between the two samples (1999 and 2004) and individual predictors showed that the predictive role of comorbidity was greater in 2004 than in 1999 (interaction term OR=4.68, CI=1.85–11.81; p=.001; data not reported in Table 3 ).

|

Contact with health services

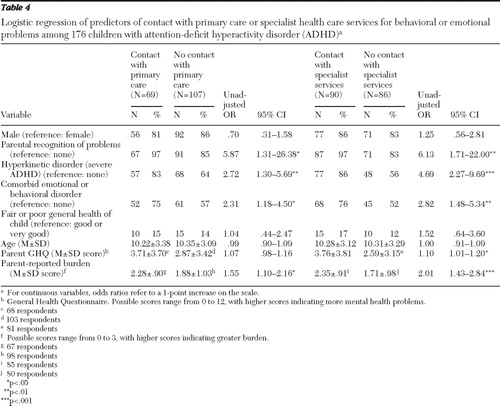

Table 4 presents findings from the analysis of predictors of contact for behavioral or emotional problems with primary care and specialist care. In the multivariable logistic regression, only severity of ADHD was associated with contact with primary care (OR=2.17, CI=1.00–4.70; p=.05). Because the predictor variables are likely to be collinear, a stepwise-forward (likelihood ratio) multivariable logistic regression was also carried out to determine whether the findings were similar. This analysis confirmed the association between severity and contact with primary care (OR=2.30, CI=1.08–4.94, p=.032), but it also found an association between parental burden and contact with primary care (OR=1.48, CI=1.05–2.08, p=.025). In the multivariable logistic regression for specialist service use, the same two factors—severity (OR=3.68, CI=1.64–8.24, p=.002) and parental burden (OR=1.83, CI=1.25–2.67; p=.002)—also predicted contact with specialist services.

|

Receipt of medication

Fifty-six children (32%) were taking medication: 52 were taking methylphenidate (alone or with something else), and one each was taking dexamphetamine, clonidine, risperidone, or amitriptyline. Time on medication ranged from one month to 11 years (median 20 months). Seven children taking medication had not been seen by a specialist service in the previous year. About half of the children being seen in a specialist health service (N=49, 54%) were taking medication. The main predictor of medication use was hyperkinetic disorder, which was present for 55 of the 56 children taking medication (98%) and 70 of the 120 children not taking medication (58%) (OR=39.29, CI=5.26–293.41, p<.001).

Trends in service use

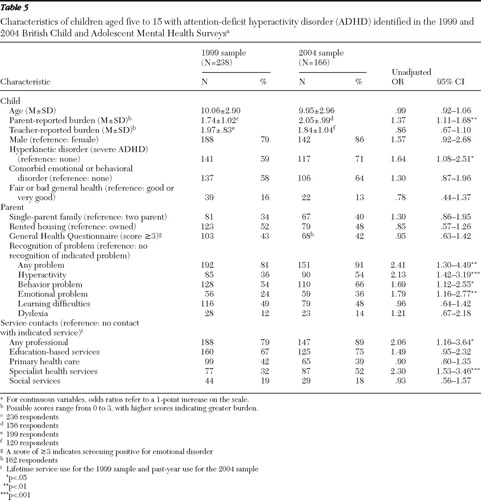

Table 5 presents data for the ADHD samples in 1999 and 2004. A multivariable logistic regression was conducted to investigate the roles of year, severity of ADHD, parental recognition that the child has hyperactivity, and parental burden as predictors of specialist service use. All four factors were associated with specialist service use: year (2004 versus 1999) (OR=1.76, CI=1.13–2.75, p=.013), severity (OR=1.68, CI=1.02–2.77, p=.043), parental recognition that the child has hyperactivity (OR=2.98, CI=1.87–4.73, p<.001), and parental burden (OR=1.35, CI=1.08–1.69, p=.009). These findings indicate that there was an increase in specialist service use by children with ADHD over the five-year period after the analysis adjusted for severity, parental recognition, and burden.

|

Discussion

Over a five-year period, specialist health service use increased among children with ADHD. This increase persisted after adjustment for factors such as severity of problems and parental perceptions. The increase was not related to change in the prevalence of ADHD between 1999 and 2004. We may have underestimated the magnitude of this increase because we compared use of services in the previous year for the 2004 sample with lifetime use of services for the 1999 sample. Our findings are in keeping with similar studies from the Netherlands and Finland that also reported increased rates of mental health service use among children over periods ranging from six to ten years and found that greater severity of symptoms predicted service use ( 27 , 28 , 29 ). However, these studies did not specifically investigate changes in service use by children who met criteria for a psychiatric disorder, and they reported mixed findings for children with more severe symptoms.

In 2004 more parents of children with ADHD recognized the presence of a problem, compared with parents in 1999. The increase was greatest for conceptualization of the problem as hyperactivity, suggesting that parental awareness of ADHD has increased over the five years. In 2004 parents of three-quarters of children with ADHD had been in contact with education-based professionals in the previous year about concerns relating to emotions, behavior, or concentration. The proportion of parents who had made health service contacts was lower, suggesting that schools and education-based professionals are the primary source of support for these families ( 29 ). This might reflect the ready visibility of behaviors related to hyperactivity in the school setting, or it might suggest that teachers are the preferred choice of professional for consultation ( 28 ). However, British teachers often do not conceptualize problems involving hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention as constituting ADHD ( 30 ). Our data highlight a role for health services in providing support and training in schools to assist with recognition and management of children who have ADHD.

In 2004 one-third of children in Britain with ADHD were taking medication for ADHD, which provides little empirical support for public concerns that such medication is overused among children. In addition, data from the wider 2004 survey provide no evidence that stimulant medication was being used inappropriately for children who did not meet criteria for hyperkinetic disorder ( 11 ). The main predictor of medication use was severity of symptoms ( 31 , 32 ). The proportion of children with ADHD taking medication is slightly higher than proportions reported for epidemiological samples in Australia and the Netherlands and for some but not all such samples in the United States ( 7 , 8 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ). However, comparisons across studies need to account for the age of the sample, the year the study was conducted, and the choice of diagnostic criteria and measures to determine the presence of ADHD. Although the prevalence of 2.2% for ADHD in the B-CAMHS is lower than in many previous studies, it is in keeping with a U.S.-based epidemiological sample ( 36 ). In Britain national guidelines have recommended that only professionals in specialist health services should make a diagnosis of ADHD and initiate medication ( 5 , 15 ). This model of diagnosis and treatment by specialists might explain why most children with ADHD in the sample were not taking medication. Medication use may decrease in the future after recent national recommendations that parent education and training should be a first-line treatment for ADHD ( 15 ).

Over the five-year period, there were notable changes in the correlates of service use. In 1999 the predictors of service use mainly reflected parental factors, such as parental recognition of problems and perceived burden ( 1 ). In contrast, in 2004 comorbidity was the main predictor of both parental recognition of problems and contact with education-based services. Health service use was predicted by severity of the disorder (the presence of hyperkinetic disorder) and parental burden. Our findings are in keeping with data from Australia showing that the combined subtype of ADHD (the closest equivalent in DSM-IV to hyperkinetic disorder) and impact on parents best predicted contact with any health services ( 8 ). Parental burden has also been found to predict recent contact with mental health services ( 20 , 21 , 37 ). Overall, our findings are encouraging because they suggest that child-related factors appear to be the main determinants of which children receive services. This suggests the possibility that key adults, such as parents, teachers, and clinicians, are increasingly taking these disorder-related factors into account in their decisions about referral and treatment.

Strengths and limitations

Particular strengths of our study include the use of two nationally representative cross-sectional surveys of nonoverlapping samples carried out in similar ways five years apart. Many studies have used pharmacoepidemiological data as a proxy for the proportion of children in the population receiving treatment for ADHD, but these studies did not provide validated information on whether the diagnostic status was accurate, relying, for example, on patient databases, prescription rates, or parent reports of clinical diagnoses ( 38 , 39 ). Population-based epidemiological studies that compare treatment information against diagnostic status at an individual level are more useful in determining treatment and medication rates. Most such studies that investigated service use for ADHD have had a regional focus, and local prescribing practices and service models might have influenced the findings ( 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ). Although a few nationally representative studies have been conducted ( 1 , 7 , 8 ), none have investigated changes in service use for ADHD over time.

We used a reliable and validated diagnostic interview measure and data from multiple informants to determine the presence of disorders. However, developmental disabilities were not formally assessed, even though they are often comorbid with ADHD. We were able to study differences over only a five-year interval. Although it is possible that some of our findings might reflect changes in how participants respond to questionnaires and interviews over time, the similar prevalence rates of ADHD in the two samples suggest that this is unlikely. The analyses were based on an a priori empirical framework used previously. Our findings from the 2004 survey overcome possible limitations of recall bias in the 1999 survey by establishing the proportion of children with ADHD in recent contact with services or using medication at the time of the interview. Although information on service and medication use was obtained from parent reports, these have been shown in British samples to be valid when compared with service records ( 40 ).

Service implications

Large-scale nationally representative studies provide useful descriptive data on use of services and treatment. Service planners at both local and national levels need accurate information on which and how many children with ADHD are identified and about factors that influence the receipt of services. The findings provide information about the effectiveness of policy and service developments, such as the availability of evidence-based treatments and, if coupled with a longitudinal component, about changes in outcome. Our data also provide a baseline for future assessment of the impact of recent national clinical guidelines in Britain.

Conclusions

In Britain the proportion of children with ADHD accessing services has increased in recent years. However, medication for ADHD appears to be used cautiously, and this study provided little empirical evidence for concerns that medication is overused among children with ADHD. There is a need for health services to support education-based professionals to help them recognize and manage ADHD among children.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Sayal K, Goodman R, Ford T: Barriers to the identification of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 47:744–750, 2006Google Scholar

2. Prendergast M, Taylor E, Rapoport JL, et al: The diagnosis of childhood hyperactivity: a US-UK cross-national study of DSM-III and ICD-9. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 29:289–300, 1988Google Scholar

3. Willoughby MT: Developmental course of ADHD symptomatology during the transition from childhood to adolescence: a review with recommendations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 44:88–106, 2003Google Scholar

4. MTA Cooperative Group: A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for ADHD. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:1073–1086, 1999Google Scholar

5. Guidance on the Use of Methylphenidate (Ritalin, Equasym) for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Childhood. Technology appraisal guidance no 13. London, National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2000Google Scholar

6. Scheffler RM, Hinshaw SP, Modrek S, et al: The global market for ADHD medications. Health Affairs 26:450–457, 2007Google Scholar

7. Froehlich TE, Lanphear BP, Epstein JN, et al: Prevalence, recognition, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a national sample of US children. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 161:857–864, 2007Google Scholar

8. Sawyer MG, Rey JM, Arney FM, et al: Use of health and school-based services in Australia by young people with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 43:1355–1363, 2004Google Scholar

9. Meltzer H, Gatward R, Goodman R, et al: Mental Health of children and adolescents in Great Britain. London, Stationery Office, 2000Google Scholar

10. Ford T, Goodman R, Meltzer H: The British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey 1999: the prevalence of DSM-IV disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 42:1203–1211, 2003Google Scholar

11. Green H, McGinnity A, Meltzer H, et al: Mental Health of Children and Young People, Great Britain 2004. London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2005Google Scholar

12. Goodman R, Ford T, Richards H, et al: The Development and Well-Being Assessment: description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 41:645–655, 2000Google Scholar

13. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

14. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1992Google Scholar

15. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Management of ADHD in Children, Young People, and Adults. Clinical Guideline 72. London, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2008Google Scholar

16. Goldberg D, Williams P: User's Guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor, United Kingdom, NFER-Nelson, 1988Google Scholar

17. Santosh PJ, Taylor E, Swanson J, et al: Refining the diagnoses of inattention and overactivity syndromes: a reanalysis of the Multimodal Treatment Study of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) based on ICD-10 criteria for hyperkinetic disorder. Clinical Neuroscience Research 5:307–314, 2005Google Scholar

18. Goodman R: The extended version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 40:791–799, 1999Google Scholar

19. Messer SC, Angold A, Costello EJ, et al: The Child and Adolescent Burden Assessment (CABA): measuring the family impact of emotional and behaviour problems. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 6:261–284, 1996Google Scholar

20. Angold A, Messer SC, Stangl D, et al: Perceived parental burden and service use for child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Public Health 88:75–80, 1998Google Scholar

21. Bussing R, Zima BT, Belin TR: Differential access to care for children with ADHD in special education programs. Psychiatric Services 49:1226–1229, 1998Google Scholar

22. Bussing R, Zima BT, Gary FA, et al: Barriers to detection, help-seeking, and service use for children with ADHD symptoms. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 30:176–189, 2003Google Scholar

23. Ford T, Hamilton H, Meltzer H, et al: Predictors of service use for mental health problems among British school children. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 13:32–40, 2008Google Scholar

24. Sayal K, Taylor E, Beecham J: Parental perception of problems and mental health service use for hyperactivity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 42:1410–1414, 2003Google Scholar

25. Verhulst FC, van der Ende J: Factors associated with child mental health service use in the community. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:901–909, 1997Google Scholar

26. Teagle SE: Parental problem recognition and child mental health service use. Mental Health Services Research 4:257–266, 2002Google Scholar

27. Tick NT, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC: Ten-year increase in service use in the Dutch population. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 17:373–380, 2008Google Scholar

28. Sourander A, Santalahti P, Haavisto A, et al: Have there been changes in children's psychiatric symptoms and mental health service use? A 10-year comparison from Finland. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 43:1134–1145, 2004Google Scholar

29. Sourander A, Niemelä S, Santalahti P, et al: Changes in psychiatric problems and service use among 8-year-old children: a 16-year population-based time-trend study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 47:317–327, 2008Google Scholar

30. Groenewald C, Emond A, Sayal K: Recognition and referral of girls with ADHD: case vignette study. Child: Care, Health and Development 35:767–772, 2009Google Scholar

31. Reich W, Huang H, Todd RD: ADHD medication use in a population-based sample of twins. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 45:801–807, 2006Google Scholar

32. Tremmery S, Buitelaar JK, Steyaert J, et al: The use of health care services and psychotropic medication in a community sample of 9-year-old schoolchildren with ADHD. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 16:327–336, 2007Google Scholar

33. Angold A, Erkanli A, Egger HL, et al: Stimulant treatment for children: a community perspective. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:975–984, 2000Google Scholar

34. Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, et al: How common is attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Incidence in a population-based birth cohort in Rochester, Minn. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 156:217–224, 2002Google Scholar

35. Jensen PS, Kettle L, Roper MT, et al: Are stimulants overprescribed? Treatment of ADHD in four US communities. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:797–804, 1999Google Scholar

36. Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, et al: Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:837–844, 2003Google Scholar

37. Sayal K: The role of parental burden in child mental health service use: longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 43:1328–1333, 2004Google Scholar

38. Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, Marcus SC, et al: National trends in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1071–1077, 2003Google Scholar

39. Visser SN, Lesesne CA, Perou R: National estimates and factors associated with medication treatment for childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 119(suppl 1):S99–S106, 2006Google Scholar

40. Ford T, Hamilton H, Dosani S, et al: The Children's Services Interview: validity and reliability. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 42:36–49, 2007Google Scholar