Lifestyle Interventions for Adults With Serious Mental Illness: A Systematic Literature Review

The elevated rates of morbidity and mortality among adults with serious mental illness (for example, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder) constitute a public health crisis ( 1 ). Individuals with serious mental illness die on average 25 years before persons in the general population, largely because of preventable medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes ( 2 ). Modifiable risk factors, including high rates of smoking, poor dietary habits, obesity, and a sedentary lifestyle, cause and aggravate the physical health needs of adults with serious mental illness ( 3 , 4 ). Moreover, medication side effects, such as secondary weight gain and metabolic alterations linked to the use of second-generation antipsychotic agents, contribute to the high prevalence of medical comorbidities and poor health outcomes documented in this population ( 5 ). These physical health needs of persons with serious mental illness are exacerbated by a lack of access to high-quality medical care ( 1 ).

In an effort to mobilize action to address these serious health disparities, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's Center for Mental Health Services formulated the "Pledge for Wellness," which promotes national efforts to prevent and reduce early mortality among persons with serious mental illness by ten years within the next decade ( 6 ). The promotion of healthy lifestyles and wellness among individuals living with serious mental illness is an integral part of the recovery process ( 7 ). A critical step in improving the physical health of adults affected by these conditions is to develop and implement effective, culturally appropriate, and sustainable lifestyle interventions. We define lifestyle interventions as structured approaches that help individuals engage in physical activity, manage their weight, eat a balanced and healthier diet, and engage in health promotion activities.

What is the current state of the U.S. literature examining lifestyle interventions for adults living with serious mental illness? This article seeks to address this question by systematically reviewing studies that report the health outcomes of lifestyle interventions evaluated in this population. Past reviews of the literature have focused mainly on weight management treatments among individuals with schizophrenia ( 8 , 9 ) or on the efficacy of behavioral interventions in managing weight gain associated with the use of second-generation antipsychotic medications ( 10 ). The review presented here builds on this previous work and provides a comprehensive literature review of interventions that not only focuses on weight but also examines exercise, health promotion, and self-management activities; expands the patient population to include other diagnostic categories (for example, bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorder) represented in the population with serious mental illness ( 11 ); and assesses the inclusion of persons from racial and ethnic minority groups in these studies. The aims of our review are to rate the methodological quality of lifestyle intervention outcome studies, summarize intervention strategies, examine health outcomes, and evaluate the inclusion of persons from racial and ethnic minority groups in these studies and the cultural and linguistic adaptations used in these interventions.

Methods

Study selection

We searched the Medline, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Cochrane Collaboration databases for lifestyle intervention studies of adults with serious mental illness conducted in the United States and published between January 1980 and January 2010. Our search strategy included combinations of the following key words: schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, serious mental illness, serious and persistent mental illness, psychiatric disorders, bipolar disorder, depression, obesity, lifestyle intervention, weight management, weight management education, cognitive-behavioral treatment, physical activity, exercise, randomized controlled trial, program evaluation, case study. This search strategy was supplemented with manual searches of the reference sections of articles, book chapters, and government reports to identify overlooked studies.

Our search yielded a total of 53 articles. The first two authors (LJC and JME) screened all articles for relevance. Eligible articles needed to be published in peer-reviewed journals between January 1980 and January 2010 and had to be written in English and conducted in the United States. In addition, these articles needed to report the physical health outcomes (for example, weight and body mass index [BMI]) or health promotion outcomes (for example, self-efficacy and health-related quality of life) of lifestyle interventions and had to include adults diagnosed or classified by the study as having serious mental illnesses, which included but was not limited to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. Thirty articles were excluded; 24 were conducted outside the United States, five were not lifestyle interventions (for example, pharmacotherapy), and one did not report physical health outcomes. In total, 23 articles were included in our review.

Analytical strategies

A data abstraction form was developed based on Lipsey and Wilson's ( 12 ) recommendations, and it was used to systematically code study characteristics, such as study aims and hypotheses, study sites, designs, sampling and randomization methods, measures, analytical strategies, sample characteristics, findings, and study limitations. We coded intervention characteristics, including intervention format, type of staff delivering the intervention, duration of the intervention, and any dimension of the interventions describing the dietary, exercise, health promotion, and behavioral modification strategies or activities employed. To rate the methodological quality of studies, we used an adapted version of the Methodological Quality Rating Scale (MQRS) ( 13 , 14 ). [An appendix showing the adapted version of the Methodological Quality Rating Scale is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org .] This instrument assesses the methodological quality of studies across 12 dimensions (for example, study design and follow-up rate). One dimension was added to the scale to assess for the presence or absence of cultural or linguistic adaptations in the lifestyle interventions. This added dimension has been used in previous systematic literature reviews ( 15 ) and enabled us to rate whether studies explicitly discussed strategies to adapt lifestyle interventions to the needs of participants from racial and ethnic minority groups. Cumulative MQRS scores for each study could range from 1, poor quality, to 17, high quality. Working independently, the first two authors (LJC, JME) used the MQRS to rate each of the 23 studies included in this review. We calculated an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) to examine the interrater reliability of the two coders on the total MQRS scores for each study. Agreement between the two coders was excellent, with an ICC of .78 (95% confidence interval=.49–.91). Differences in MQRS rating were resolved through consensus.

Results

Study characteristics

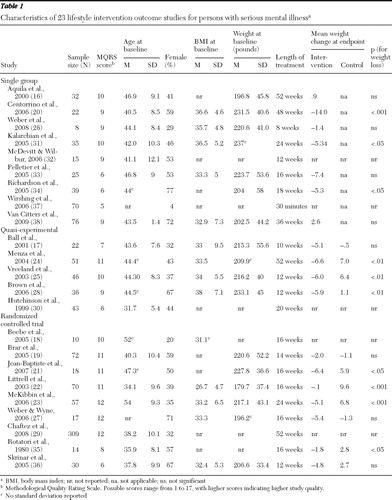

Table 1 displays study characteristics. Study samples ranged in size from eight to 309 adult participants, with a median of 35. Participants' average age across studies ranged from 32 to 54 years (median=44). The percentage of female participants ranged from 4% to 77% (median=44%). The mean±SD weight at baseline across studies was 213.9±15 pounds, and the mean BMI at baseline was 33.6±2.7. (A BMI score <18.5 indicates that the person is underweight; 18.5–24.9, normal weight; 25.0–29.9, overweight; and ≥30, obese.) Twelve studies (52%) restricted their sample to individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders ( 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ). The other 11 studies investigated other mental disorders, which included but were not limited to major depression, bipolar disorder, alcohol dependence, and anxiety disorders ( 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ). Intervention sites included a range of treatment settings, such as inpatient units, day treatment programs, outpatient clinics, residential facilities, clubhouses, and vocational agencies.

|

Six studies did not specify inclusion criteria that required participants to take specific psychotropic medications at the time of enrollment and did not enumerate the type of medication that participants were taking ( 28 , 29 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 38 ). Four studies did not specify medication inclusion criteria, but they did enumerate in a general manner (for example, second-generation antipsychotic medications) the type of medications that participants were taking at the time of enrollment ( 18 , 23 , 30 , 33 ). The rest of the studies specified medication inclusion criteria that were either restricted to monotherapy with one antipsychotic medication at the time of enrollment ( 26 , 27 ) or combination treatment of one antipsychotic with other psychotropics ( 16 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 25 , 31 , 32 , 36 ). Three studies restricted their intervention to patients taking olanzapine ( 17 , 19 , 22 ). Only one study was designed to test the weight loss effects of a lifestyle intervention among patients who switched from olanzapine to risperidone ( 19 ).

Methodological characteristics and quality ratings

The majority of studies reviewed were single-site studies (N=20, 87%), counted treatment dropouts (N=20, 87%), and used a manualized intervention design (N=16, 70%). Treatment retention rates varied markedly, ranging from 31% to 100%, with a mean of 70%±17%. Study endpoints ranged in duration from 30 minutes to 18 months, with a median of 16 weeks. The majority of studies (N=19, 83%) did not use assessors who were blind to study participants' treatment condition. In addition, no study included interviews with collaterals, such as study participants' relatives or friends, to assess process or outcome measures. Follow-up assessments consisted of self-report measures, structured interviews, laboratory tests, and physical examinations. Statistical procedures used to evaluate intervention outcomes included but were not limited to paired t tests, mixed-model analysis of variance, and multilevel regressions.

MQRS scores for each study are reported in Table 1 . The total MQRS score across studies ranged from 5 to 12, with a mean score of 9.1±2.2, suggesting a wide spectrum of methodological quality. At the lower end of the spectrum are nine studies (39%) that utilized a single-group, pre-post design and received a mean MQRS score of 8.1±1.9. The majority of these nine studies were single-site studies (N=8, 89%), many did not use manualized interventions (N=4, 44%), and none used blind assessors. In the middle of the methodological quality spectrum are five studies (22%) that used quasi-experimental designs that compared a treatment condition with a usual care or waitlist group. The mean MQRS score for these studies was 8.6±2.1. Most of these five studies were also single-site studies (N=4, 80%), two (40%) did not use manualized interventions, and none used blind assessors. In contrast to the single-group studies, quasi-experimental studies provided more details about their intervention and study procedures. All of these studies counted treatment dropout rates and used anthropometric assessments instead of self-reports to measure health outcomes (for example, BMI). At the highest level of the quality spectrum are nine studies (39%) that were randomized controlled trials. These studies had the highest MQRS scores (mean of 10.3±2.1). Compared with the other types of studies, a higher proportion of randomized controlled trials used assessors that were blinded to participants' group assignments (N=4, 44%) and used manualized interventions (N=8, 89%).

Intervention characteristics

Lifestyle interventions ranged in duration from 30 minutes ( 37 ) to 52 weeks ( 16 , 24 ). Intervention formats featured individual sessions ( 29 ) and group sessions ( 16 , 17 , 19 , 21 , 23 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 37 ), with some integrating both approaches ( 20 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 38 ). Interventions were delivered by a range of staff, including registered nurses, exercise physiologists, registered dieticians, trained fitness instructors, case managers, and master's- and doctoral-level health care practitioners. All interventions provided general information about diet, exercise, and health promotion. Interventions that focused on dietary practices included the following strategies: teaching participants about reading food labels and counting calories; food diaries; portion control; meal planning; eating slowly; increasing intake of fruits, vegetables, water, and diet sodas; and decreasing consumption of foods high in fat, sodium, and sugar. Several interventions incorporated more action-oriented approaches to model and enhance dietary skills, such as grocery store visits ( 20 , 21 ) and cooking demonstrations ( 21 ). Interventions that incorporated exercise elements included warm-up and stretching exercises, aerobic exercises (for example, walking and riding a stationary bike), and individualized fitness training. The physical activity goal across interventions was to gradually increase physical activity to 30–45 minutes three to five times a week. Some interventions gave participants pedometers, heart rate monitors, or both to monitor physical activity. A few interventions taught participants how to take their pulse. Most interventions incorporated behavioral strategies, including goal setting, feedback, skills training, problem solving, social support, motivational counseling, stress management, relapse prevention, assertiveness training, rewards or token reinforcements, stimulus control, and risk and benefit comparisons. Finally, several interventions incorporated specific teaching techniques to address the motivational impairment and cognitive deficits associated with serious mental illness. These techniques were used to enhance retention and comprehension among participants and included simplification of handout materials and printing the material with large font sizes, using educational games, repetition of lessons and modules, frequent homework or quizzes, reading aloud, and integrating mnemonic aides and visual materials.

Weight loss outcomes

Eighteen studies—seven single-group pre-post designs, four quasi-experimental trials, and seven randomized controlled trials—conducted statistical analyses to determine whether the lifestyle intervention resulted in significant weight loss from baseline to follow-up or between treatment conditions. Ten of these 18 studies reported statistically significant weight loss findings ( Table 1 ). Weight loss outcomes by study type are reported below.

Among the seven single-group studies, the average weight change at the completion of treatment ranged from losing 14 pounds to gaining 2.6 pounds, with a mean loss of 4.3±5.6 pounds. Four of the seven studies did not find statistically significant weight loss outcomes: two were weight management studies ( 16 , 26 ), one was an exercise program ( 33 ), and the fourth was a health promotion program ( 38 ). The other three studies—all weight loss programs ( 20 , 31 , 34 )—reported statistically significant weight loss outcomes. For example, Richardson and colleagues ( 34 ) found a significant pre-post weight loss of five pounds among participants who completed their 18-week physical activity intervention (N=10). Centorrino and colleagues ( 20 ) found that patients who completed 24 weeks of treatment lost an average of 14 pounds and reduced their BMI from 36.6 to 34.5. These decreases in weight and BMI were statistically significant from baseline to 24 weeks and were sustained at 48 weeks.

Among the four quasi-experimental studies, the average weight loss for the intervention groups at study endpoints ranged from 6.6 to 5.1 pounds, with a mean loss of 5.9±.6 pounds. All were weight loss programs. Three of the four studies reported that their intervention groups achieved statistically significant weight loss when they were compared with usual care groups. Vreeland and colleagues ( 25 ) and Brown and colleagues ( 28 ) reported an average weight loss of approximately six pounds and an average reduction in BMI of 1.0 at the end of 12 weeks of treatment. Similarly, Menza and colleagues ( 24 ) reported that treatment resulted in significant weight loss and change in BMI, compared with usual care, averaging 6.6 pounds at 52 weeks and an average BMI reduction of 1.7.

Among the seven randomized controlled trials, the average weight loss for the intervention groups at study endpoints ranged from 6.4 to .1 pounds, with a mean loss of 3.7±2.3 pounds. Three of the seven randomized controlled trials did not find statistically significant weight loss outcomes. Two were weight loss programs ( 10 , 27 ), and one was a fitness intervention ( 36 ). The other four randomized controlled trials—all weight loss programs—reported that their program participants achieved statistically significant weight loss when they were compared with their respective control groups. Rotatori and colleagues ( 35 ) and Jean-Baptiste and colleagues ( 21 ) reported significant between-group differences favoring their lifestyle intervention groups, with the lifestyle intervention groups having an average weight loss of 7.3 and 6.4 pounds, respectively, at the completion of treatment. Littrell and colleagues ( 22 ) found that compared with a usual care group, their intervention group gained significantly less weight at the end of a 16-week treatment (average gain of .81 pounds versus an average gain of 7.2 pounds) and that this trend continued through a 24-week follow-up period (average loss of .06 pounds versus an average gain of 9.6 pounds). Similarly, McKibbin and colleagues ( 23 ) reported that compared with individuals in a usual care group, those randomly assigned to a 24-week intervention achieved a statistically significant weight loss averaging 5.1±2.8 pounds, with a .70±.2 reduction in BMI.

Metabolic syndrome risk factor outcomes

Thirteen studies assessed whether lifestyle interventions improved risk factors for metabolic syndrome, including systolic blood pressure (sBP) and diastolic blood pressure (dBP), heart rate, blood glucose, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and waist and hip circumference ( 19 , 20 , 21 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 38 ). Seven studies reported statistically significant improvements on at least one of these risk factors.

Three studies reported significant effects on sBP ( 19 , 20 , 24 ), and two reported significant effects on dBP ( 20 , 24 ). Centorrino and associates ( 20 ) reported a significant mean reduction of sBP (11%) and dBP (11%) in their intervention group from baseline to the end of treatment at 28 weeks. Brar and colleagues ( 19 ) found a statistically significant reduction in sitting sBP (4%) and standing sBP (5%) from baseline to the end of their 14-week intervention. These reductions in sBP were not observed in their usual care group. Similarly, Menza and colleagues ( 24 ) reported that their intervention group had a statistically significant reduction in both sBP (3%) and dBP (7%) from baseline to the conclusion of their 52-week program. Other risk factors (for example, sBP, dBP, and triglyceride levels) besides weight and BMI in this study were collected only for the intervention group and not the comparison group.

Two studies reported significant improvements in blood glucose levels or hemoglobin A1C. In post hoc analyses that included only participants in their weight loss program who lost weight, Jean-Baptiste and colleagues ( 21 ) found that these individuals also had statistically significant decreases in mean fasting blood glucose levels between baseline (102.8±5.4 mg/dl) and the six-month follow-up (92.8± 9.3 mg/dl), representing a 10% overall reduction. (Normal fasting blood glucose levels range from 70 to 90 mg/dl.) Menza and colleagues ( 24 ) also reported statistically significant reductions in hemoglobin A1C (5%) from baseline to the end of their 52-week program.

One study reported significant improvements in triglyceride levels ( 23 ), and four studies reported significant improvement in central adiposity levels (that is, waist or hip circumference or both) ( 23 , 24 , 28 , 38 ). McKibbin and colleagues ( 23 ) found that after the analysis adjusted for baseline triglyceride levels and negative psychiatric and depressive symptoms across study groups, the intervention group achieved a statistically significant 16% reduction in mean triglyceride levels by the end of the 24-week program. Brown and colleagues ( 28 ) and McKibbin and colleagues ( 23 ) found that compared with the respective control groups, their interventions produced statistically significant reductions in waist circumference from baseline to study endpoints, averaging 3%. Menza and colleagues ( 24 ) also reported that within their intervention groups there was a statistically significant reduction in waist circumference, averaging 3%; they also reported a hip measurement reduction averaging 3% from baseline to intervention endpoint at 52 weeks. Finally, Van Citters and colleagues ( 38 ) reported that participants in their health promotion program lost an average of 3.2 cm (1.3 in) in waist circumference from baseline to the study endpoint at the nine-month follow-up, which was a significant change.

Cultural adaptations for racial and ethnic minority groups

Fourteen studies (61%) reported the racial and ethnic makeup of their sample. The total sample size across these 14 studies was 776: 415 (53%) were non-Hispanic whites, 183 (24%) were African Americans, 45 (6%) were Hispanics, 29 (4%) were Asian Americans, and 104 (13%) were from other racial or ethnic groups. In regard to cultural and linguistic adaptations, only one study—a case report of eight Spanish-speaking Hispanic patients—explicitly adapted a program for a minority group; the Diabetes Prevention Program ( 39 ) was adapted for this group ( 26 ). This was the only study to include non-English-speaking participants. Adaptations by Weber and colleagues ( 26 ) entailed changing the format of the intervention from individual to group sessions to increase socialization and enhance the usability of the intervention in community mental health settings with limited resources, shortening the intervention from 16 to eight weeks, delivering the intervention in Spanish, and modifying the Diabetes Prevention Program content to accommodate local needs, such as obtaining menus from frequented fast-food restaurants and suggesting the healthiest options. Only one study examined racial and ethnic differences in treatment outcomes. Littrell and colleagues ( 22 ) reported that in both the intervention and control groups, African Americans gained more weight than non-Hispanic whites. However, these racial differences were not statistically significant. In sum, these results point to a serious underrepresentation of persons from racial and ethnic minority groups in lifestyle intervention studies among adults with serious mental illness and a lack of attention to cultural and linguistic factors in this area of research.

Discussion

Aims of study

Lifestyle interventions are essential in lowering the risk and morbidity associated with preventable medical conditions (for example, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes) experienced by adults with serious mental illness. The goal of this study was to provide a systematic literature review of lifestyle interventions tested in the United States aiming to improve the physical health of this at-risk population. To this end, we found 23 studies and focused our review on four key aspects.

Our first aim was to rate studies' methodological quality. The findings from the MQRS ratings suggest three levels of evidence corresponding to the degree of internal validity of the studies. At the lowest level were the nine uncontrolled studies that relied on single-group pre-post designs. These studies tended to have small sample sizes and to vary in treatment length (treatment length ranged from 30 minutes to 52 weeks). In addition, many of these studies (N=4, 44%) did not use manualized interventions. At the second level of evidence were the five studies that utilized quasi-experimental methods. Similar to the uncontrolled studies in level 1, these quasi-experimental studies consisted of open trials with small samples that varied in treatment length (ten to 52 weeks), and two did not use a manualized intervention. These trials, however, controlled for more threats to internal validity than studies in level 1 by comparing treatment effects between an intervention group and a comparison group (for example, usual care group) and by employing statistical controls to adjust for group differences and minimize selection bias.

At the highest level of methodological quality were the nine randomized controlled trials. These studies ranged in sample size from ten to 309 participants, most used manualized interventions, and treatment ranged from 12 to 52 weeks. A major limitation of these randomized controlled trials was that four did not use blind assessors to measure treatment outcomes, thus introducing the possibility of assessment bias. Future randomized controlled trials in this area should consider using assessors blinded to participants' assignment in order to reduce unintended bias in data collection.

Studies' methodological ratings also suggest that this literature is mostly based on small, single-site efficacy trials, thus limiting the external validity of this evidence to real-world mental health settings. Aside from the study by Chafetz and colleagues ( 29 ), the studies had small samples ranging from eight to 76 participants. Moreover, most studies were single-site trials, usually in academic settings, limiting the generalizability of these findings to community settings that have limited resources and infrastructure to support these interventions. Finally, the small number of persons from racial and ethnic minority groups included in these studies restricts the generalizability of their results to diverse populations. These methodological findings suggest that more rigorous methods are needed to advance the knowledge base in this area, particularly multisite randomized controlled trials that include racially and ethnically diverse samples and are conducted in collaboration with providers and organizations outside the confines of academic institutions.

Our second aim was to examine intervention characteristics. Across the studies reviewed, goals of the interventions were to enhance participants' knowledge of nutrition, physical activity, and general health promotion; to impart skills regarding healthy eating, weight management, and exercise; and to provide support for sustaining lifestyle behavioral changes. Twelve studies reported statistically significant improvements in either weight loss or metabolic syndrome risk factors associated with their lifestyle interventions. These interventions for individuals with serious mental illness were informed and adapted from existing lifestyle interventions originally developed and used in the general population. All used a group format or a combination of group and individual sessions to deliver the intervention. Similar to the approaches proven effective in the general population for reducing weight ( 40 , 41 ) and decreasing risk factors for chronic medical conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes ( 39 , 42 ), most interventions used dietary counseling and an exercise regimen of light-to-moderate physical activity (for example, walking). Finally, all of these studies incorporated common behavioral techniques (for example, problem solving, goal setting, and self-monitoring) into their interventions. It is difficult to tease out from the existing studies which of these intervention features accounted for the greatest variance in health outcomes for individuals with serious mental illness because of the differences in samples, sites, and outcome measures used across studies. Findings of this nature make inferences untenable. More work in this area is needed to identify the core intervention elements that are most beneficial and cost-effective for improving the health of persons with serious mental illness.

Our third aim was to examine the effects that lifestyle interventions had on health outcomes, particularly weight loss and risk factors for preventable medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Both types of outcomes are important health indicators for individuals with mental illnesses because they are linked to the elevated mortality and morbidity reported in this population ( 43 ).

Ten of the 18 studies that reported data on weight loss found statistically significant reductions in weight associated with receiving a structured lifestyle intervention. However, the average weight loss in these ten studies varied by study design. The mean weight loss for the three single-group studies ( 20 , 31 , 24 ) was 8.2±5 pounds, whereas the three quasi-experimental studies ( 24 , 25 , 28 ) and four randomized controlled trials ( 21 , 22 , 23 , 35 ) showed more modest average weight loss (6.2±.4 pounds and 3.4±2.9 pounds, respectively). The mean for the randomized controlled trials reviewed falls below the mean weight loss reported in meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of lifestyle interventions tested in the general population, which was eight to 11 pounds ( 44 , 45 ). The difference in weight loss outcomes between the general population and persons with serious mental illness may be due to variability in treatment intensity, worse health status at baseline among persons with serious mental illness, or methodological differences across studies. Our review shows that persons with serious mental illness may benefit from lifestyle interventions, although possibly to a lesser extent than the general population, but variability in study design and rigor limits the identification of the most beneficial interventions for achieving weight loss in this at-risk population. More research in this area is warranted to understand and enhance the weight loss outcomes of lifestyle interventions for individuals with serious mental illness.

Seven of the 13 studies that examined the benefits of lifestyle interventions on metabolic syndrome risk factors had statistically significant findings. These seven studies used a range of methodologies. Two were single-group studies ( 20 , 28 ), two were quasi-experimental studies ( 24 , 28 ), and three were randomized controlled trials ( 19 , 21 , 23 ). These studies reported positive effects on sBP and dBP, blood glucose and triglyceride levels, and central adiposity. Methodological variability among these studies prevented us from identifying the most effective interventions for reducing the risk of metabolic syndrome among persons with serious mental illness. Even though these risk factors were secondary outcomes and only a limited number of studies explored these effects, these findings seem promising because improvements in these risk factors may exert a bigger health benefit than weight loss ( 46 ). Because of the high prevalence of obesity and chronic medical illnesses among persons with serious mental illness and the negative metabolic alterations associated with second-generation antipsychotics ( 43 , 47 ), future trials need to be properly powered to examine the effect of lifestyle interventions on these risk factors.

Our fourth and last aim was to examine the inclusion of persons from racial and ethnic minority groups in these studies and the cultural and linguistic adaptations of these interventions. Our findings show a serious underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minorities in the studies reviewed, particularly for Hispanics, Asian Americans, and the non-English-speaking populations in the United States. There is also a true neglect of cultural and linguistic issues within this literature. Only one study included non-English-speaking participants and culturally adapted the lifestyle intervention to fit the needs of a small group of Spanish-speaking Hispanic patients ( 26 ). Aside from Weber and colleagues' study ( 26 ), we know of one other quasi-experimental study that was recently completed that also adapted a lifestyle intervention for Hispanic outpatients with serious mental illness ( 48 ). More work in this area is clearly needed given the prevalence of racial and ethnic health disparities in the United States ( 49 ).

Linguistic and cultural adaptations are essential to make lifestyle interventions relevant and effective for persons from racial and ethnic minority groups. The most basic level of cultural sensitivity is to provide the intervention and its materials in the dominant language of the target group ( 50 ). Linguistic accessibility is essential to achieve cultural competence, but it is not sufficient. Attention to linguistic strategies alone could create a situation in which access to a lifestyle intervention is improved but the approach and content of the intervention is incongruent with patients' cultural norms, values, and preferences, which makes the intervention culturally inappropriate and ineffective ( 51 ). For instance, diet is inherently cultural. A lifestyle intervention that presents dietary options that are in conflict with participants' cultural traditions and their socioeconomic reality in regard to food choices and meal preparation will most likely result in resistance to dietary changes and dropout from the program. In addition, ideal body image varies across cultures, with some African-American and Hispanic groups favoring a fuller body ideal ( 52 , 53 ). Unaddressed, this can lead to the perception among participants that the lifestyle intervention is insensitive or even racist. Attention to key cultural elements that have an impact on lifestyle intervention, such as diet, exercise, body image, and health promotion need to be carefully considered in order to make interventions culturally appropriate. This can also enhance treatment engagement, retention, and ultimately physical health outcomes. More work in this area is needed to identify which intervention elements require cultural adaptation and to test the efficacy of these interventions with minority populations.

Limitations

Our review has several limitations. The differences in outcome measures (particularly for metabolic syndrome risk factors), small samples, and the heterogeneity of study designs prevented us from conducting a meta-analysis. In any systematic review, there is always the possibility of missing published studies that met preset inclusion criteria. We used multiple databases and manual searches to reduce this possibility. Another limitation is that very few studies examined and controlled for the confounding effects of antipsychotic medications on health outcomes ( 19 , 22 ). More rigorous studies are needed to control for these confounding medication effects. An important area of future work is to compare the safety and efficacy of combining different treatment regimens (for example, switching medication alone versus switching plus lifestyle intervention) for improving the physical health of persons living with serious mental illness. Publication bias of positive trials may overestimate the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions included in this review. Finally, no measurement technique is free of error. To minimize errors in our ratings of studies' methodological quality, we used an established measure, multiple independent raters, and resolved rating differences through specified consensus procedure.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that lifestyle interventions that combine exercise, dietary counseling, and health promotion show promise in addressing some of the physical health needs of people with serious mental disorders. These interventions can be integrated into health and wellness efforts to improve the health and well-being of individuals living with serious mental illness, enhance their recovery, and ultimately reduce premature mortality. As the evidence in this area continues to grow, studies are needed to assess the cultural congruence, cost-effectiveness, implementation, and sustainability of these lifestyle interventions in real-world community settings to close the gap between research and practice. The growth of the unmet health needs of adults with serious mental illness requires systematic efforts by mental health professionals of all disciplines to enhance their training, knowledge, and skills in these critical health issues and use evidence-based approaches to improve patients' recovery and quality of life.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by the New York State Office of Mental Health through funds to the New York State Center of Excellence for Cultural Competence at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. The authors thank Hannah Carliner, M.P.H., Pamela Y. Collins, M.D., M.P.H., Rebeca Aragón, B.S., Andel Nicasio, M.S.Ed., Angela Parcesepe, M.P.H., M.S.W., Denise Reed, M.B.A., M.P.H., Elizabeth Siantz, M.S.W., Ron Turner, B.A., Madeline Tavarez, B.S., and Nelson Cordero, M.D., for providing comments on previous versions of this article.

Dr.Lewis-Fernández has received research grant support from Eli Lilly and Company. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Druss BG: Improving medical care for persons with serious mental illness: challenges and solutions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 68(suppl 4):40–44, 2007Google Scholar

2. Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, et al (eds): Morbidity and Mortality in People With Serious Mental Illness. Alexandria, Va, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, Medical Directors Council, 2006Google Scholar

3. Compton MT, Daumit GL, Druss BG: Cigarette smoking and overweight/obesity among individuals with serious mental illnesses: a preventive perspective. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 14:212–222, 2006Google Scholar

4. Richardson CR, Faulkner G, McDevitt J, et al: Integrating physical activity into mental health services for persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 56:324–331, 2005Google Scholar

5. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, et al: Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:267–272, 2004Google Scholar

6. Manderscheid RW: The 10 by 10 goal. Behavioral Healthcare, Jan 2008Google Scholar

7. Silverstein SM, Bellack AS: A scientific agenda for the concept of recovery as it applies to schizophrenia. Clinical Psychology Review 28:1108–1124, 2008Google Scholar

8. Faulkner G, Soundy AA, Lloyd K: Schizophrenia and weight management: a systematic review of interventions to control weight. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 108:324–332, 2003Google Scholar

9. Loh C, Meyer JM, Leckband SG: A comprehensive review of behavioral interventions for weight management in schizophrenia. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 18:23–31, 2006Google Scholar

10. Gabriele JM, Dubbert PM, Reeves RR: Efficacy of behavioural interventions in managing atypical antipsychotic weight gain. Obesity Reviews 10:442–455, 2009Google Scholar

11. Kessler RC, Berglund PA., Bruce ML, et al: The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Services Research 36:987–1007, 2001Google Scholar

12. Lipsey MW, Wilson DB: Practical Meta-Analysis. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 2001Google Scholar

13. Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M: The efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 71:843–861, 2003Google Scholar

14. Vaughn MG, Howard MO: Integrated psychosocial and opiod-antagonist treatment for alcohol dependence: a systematic review of controlled evaluations. Social Work Research 28:41–53, 2004Google Scholar

15. Cabassa LJ, Hansen M: A systematic review of depression treatments in primary care for Latino adults. Research on Social Work Practice 17:494–503, 2007Google Scholar

16. Aquila R, Emanuel M: Interventions for weight gain in adults treated with novel antipsychotics. Primary Care Companion, Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2:20–23, 2000Google Scholar

17. Ball MP, Coons VB, Buchanan RW: A program for treating olanzapine-related weight gain. Psychiatric Services 52:967–969, 2001Google Scholar

18. Beebe LH, Tian L, Morris N, et al: Effects of exercise on mental and physical health parameters of persons with schizophrenia. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 26:661–676, 2005Google Scholar

19. Brar JS, Ganguli R, Pandina G, et al: Effects of behavioral therapy on weight loss in overweight and obese patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66:205–212, 2005Google Scholar

20. Centorrino F, Wurtman JJ, Duca KA, et al: Weight loss in overweight patients maintained on atypical antipsychotic agents. International Journal of Obesity 30:1011–1016, 2006Google Scholar

21. Jean-Baptiste M, Tek C, Liskov E, et al: A pilot study of a weight management program with food provision in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 96:198–205, 2007Google Scholar

22. Littrell KH, Hilligoss NM, Kirshner CD, et al: The effects of an educational intervention on antipsychotic induced weight gain. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 35:237–241, 2003Google Scholar

23. McKibbin CL, Patterson TL, Norman G, et al: A lifestyle intervention for older schizophrenia patients with diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Schizophrenia Research 86:36–44, 2006Google Scholar

24. Menza M, Vreeland B, Minsky S, et al: Managing atypical antipsychotic-associated weight gain: 12-month data on a multimodal weight control program. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:471–477, 2004Google Scholar

25. Vreeland B, Minsky S, Menza M, et al: A program for managing weight gain associated with atypical antipsychotics. Psychiatric Services 54:1155–1157, 2003Google Scholar

26. Weber M, Colon M, Nelson M: Pilot study of a cognitive behavioral group intervention to prevent further weight gain in Hispanic individuals with schizophrenia. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association 13:353–359, 2008Google Scholar

27. Weber M, Wyne K: A cognitive/behavioral group intervention for weight loss in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics. Schizophrenia Research 83:95–101, 2006Google Scholar

28. Brown C, Goetz J, Van Sciver A, et al: A psychiatric rehabilitation approach to weight loss. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 29:267–273, 2006Google Scholar

29. Chafetz L, White M, Collins-Bride G, et al: Clinical trial of wellness training: health promotion for the mentally ill. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 196:475–483, 2008Google Scholar

30. Hutchinson DS, Skrinar GS, Cross C: The role of improved physical fitness in mental health and recovery. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 22:355–359, 1999Google Scholar

31. Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Levine MD, et al: Behavioral treatment of obesity in patients taking antipsychotic medications. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66:1058–1063, 2005Google Scholar

32. McDevitt J, Wilbur J: Exercise and people with serious, persistent mental illness. American Journal of Nursing 106:50–54, 2006Google Scholar

33. Pelletier JR, Nguyen M, Bradley K, et al: A study of a structured exercise program with members of an ICCD Certified Clubhouse: program design, benefits, and implications for feasibility. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 29:89–96, 2005Google Scholar

34. Richardson CR, Avripas SA, Neal DL, et al: Increasing lifestyle physical activity in patients with depression or other serious mental illness. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 11:379–388, 2005Google Scholar

35. Rotatori AF, Fox R, Wicks A: Weight loss with psychiatric residents in a behavioral self control program. Psychological Reports 46:483–486, 1980Google Scholar

36. Skrinar GS, Huxley NA, Hutchinson DS, et al: The role of a fitness intervention on people with serious psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 29:122–127, 2005Google Scholar

37. Wirshing DA, Smith RA, Erickson ZD, et al: A wellness class for inpatients with psychotic disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 12:24–29, 2006Google Scholar

38. Van Citters AD, Pratt SI, Jue K, et al: A pilot evaluation of the In SHAPE individualized health promotion interventions for adults with mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, Dec 10, 2009 [Epub ahead of print]Google Scholar

39. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al: Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. New England Journal of Medicine 346:393–403, 2002Google Scholar

40. Dansinger ML, Tabsioni A, Wong JB, et al: Meta-analysis: the effect of dietary counseling for weight loss. Annals of Internal Medicine 147:41–50, 2007Google Scholar

41. Tsai AG, Wadden TA: Systematic review: an evaluation of major commercial weight loss programs in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine 142:56–66, 2005Google Scholar

42. Elmer PJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, et al: Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on diet, weight, physical fitness, and blood pressure control: 18-month results of a randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine 144:485–495, 2006Google Scholar

43. Allison DB, Newcomer JW, Dunn AL, et al: Obesity among those with mental disorders: a National Institute of Mental Health Meeting Report. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 36:341–350, 2009Google Scholar

44. Douketis JD, Macie C, Thabane L, et al: Systematic review of long-term weight loss studies in obese adults: clinical significance and applicability to clinical practice. International Journal of Obesity 29:1153–1167, 2005Google Scholar

45. Franz MJ, Vanwormer JJ, Crain AL, et al: Weight-loss outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 107:1755–1767, 2007Google Scholar

46. Lee CMY, Huxley R, Wildman R, et al: Indices of abdominal obesity are better discriminators of cardiovascular risk factors than BMI: a meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 61:646–653, 2008Google Scholar

47. Newcomer JW, Haupt DW: The metabolic effects of antipsychotic medications. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 51:480–491, 2006Google Scholar

48. Mangurian C, Chaudhry S, Amiel J, et al: Adaptation of a weight loss program for Latino patients in a community mental health clinic. Poster presented at Critical Research Issues in Latino Mental Health Annual Conference, New Brunswick, NJ, June 11, 2009Google Scholar

49. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR (eds): Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2002Google Scholar

50. Rogler LH, Malgady RG, Constantino G, et al: What do culturally sensitive mental health services means? The case of Hispanics. American Psychologist 42:565–570, 1987Google Scholar

51. Kreuter MW, Lukwago SN, Bucholtz DC, et al: Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: targeted and tailored approaches. Health Education and Behavior 30:133–146, 2003Google Scholar

52. Fitzgibbon ML, Blackman LR, Avellone ME: The relationship between body image discrepancy and body mass index across ethnic groups. Obesity Research 8:582–589, 2000Google Scholar

53. Befort CA, Thomas JL, Daley CM, et al: Perceptions and beliefs about body size, weight, and weight loss among obese African American women: a qualitative inquiry. Health Education and Behavior 35:410–426, 2008Google Scholar