Predictors of Perceived Benefit Among Patients Committed by Court Order in the Netherlands: One-Year Follow-Up

A review of the outcomes of compulsory admission showed that between 39% and 81% of patients later regarded their involuntary admission to have been justified or beneficial ( 1 ). Patients who realize in retrospect that they have benefited from commitment might be better able to derive greater benefit from future psychiatric treatment. If main factors associated with benefit perception could be identified, specific interventions might help alleviate negative effects of involuntary admission. However, few studies have examined predictors of retrospective evaluations of compulsory admission ( 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ). Study results on associations between perceived benefit and age, gender, marital status, diagnosis, and past admissions were inconclusive. Living alone, poor global functioning at the time of admission, and initial satisfaction with treatment have been found to be associated with a more positive retrospective judgment of involuntary admission ( 6 ), but these factors create little opportunity for further improvement. Additional patient characteristics and aspects of service delivery have to be identified to develop and tailor intervention programs that support a positive assessment of compulsory admission.

The study presented here aimed to identify main baseline factors associated with perceived benefit of involuntary hospitalization. The study involved all psychiatric inpatient services in a circumscribed catchment area in the Netherlands, the greater Rotterdam district. The district has a mix of urban and rural areas and about 1.2 million inhabitants. In line with common patterns of legal regulations across Europe ( 7 ), the Dutch Act on Exceptional Admissions to Psychiatric Hospitals stipulates that persons with mental illness who are aged 12 or older can be involuntarily hospitalized if their mental disorder poses a danger to themselves or others and if involuntary admission is the only way to prevent this danger. Recognition of the civil rights of psychiatric patients includes their right to refuse treatment. Additional types of coercive treatment, such as seclusion or forced medication, are documented and reported to the national Healthcare Inspectorate. In most cases, patients will first be detained in psychiatric admission wards under an emergency procedure, after which a court-ordered admission can provide a legal basis for a prolonged involuntary stay in a general psychiatric hospital. At the request of the public prosecutor, an appointed judge can authorize detention, initially allowing hospitalization for a maximum of six months.

In a prospective observational study of court-ordered admissions, we evaluated four groups of variables as possible predictors of perceived benefit: demographic variables (including ethnicity, education level, and housing), psychiatric history, clinical variables (including severity of symptoms, substance dependence, and reason for admission), and psychosocial variables (illness insight, service engagement, and perceived coercion).

Methods

Over an 18-month period from January 2005 until July 2006, patients from all of the psychiatric services in the greater Rotterdam district (three general psychiatric hospitals and the psychiatric department of a university medical center) were asked to participate in our study. Clinicians registered court-ordered admissions for 403 individual patients. Study participants had to meet the following inclusion criteria: court-order procedure had officially started, patients were 18 years or older at the time that they were asked to participate, and baseline measurements were able to be gathered within one month of patient agreement to participate. Inclusion terms were applied strictly to achieve comparable admission duration at baseline. In 127 cases (32%) researchers were unable to contact the patient soon after hospitalization, mainly because of logistical problems. Diagnosis of organic psychiatric disease (such as Alzheimer's disease) was an exclusion criterion. We also excluded patients who themselves had requested a court-ordered admission, patients who had already been committed on this basis, and patients for whom a prolongation of a court order had been requested by the clinician.

The research protocol was approved by the local research ethics committee (Erasmus MC, Rotterdam). Patients were given a complete description of the study, and written informed consent was obtained.

A total of 276 eligible patients were contacted for participation in the study. Fourteen patients (5%) were reluctant to sign the informed consent but were included because they orally agreed to participate. Sixty-nine patients (25%) refused to participate, in most cases because they did not want to be interviewed. In terms of age, sex, and diagnosis, nonrespondents did not differ from respondents. Twenty-eight of the 207 participants were excluded because the request for the index court-ordered admission was rejected (N=21) or because an outpatient commitment order was issued (N=7). The remaining 179 patients (86%) were all committed by court order and were interviewed at baseline. Five patients (3%) were lost to follow-up, leaving a final sample of 174 patients.

Data on demographic characteristics and the use of psychiatric services were collected from medical records. Psychiatric diagnosis was established with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview ( 8 ), and symptom severity was scored with the 24-item version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) ( 9 , 10 ). (Possible BPRS scores range from 24 to 168, with higher scores indicating more severe psychopathology.) Functioning was assessed with the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) ( 11 ). (Possible GAF scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning.) Reasons for admission (whether patients were dangerous to themselves or others) were documented as part of the involuntary admission procedure. Psychosocial data consisted of illness insight, which was measured by the Schedule for the Assessment of Insight ( 12 , 13 ); service engagement, which was measured by the 14-item Service Engagement Scale ( 14 ); and perceived coercion, which was measured with a 15-item questionnaire ( 15 ). (Possible Schedule for the Assessment of Insight scores range from 0 to 28, with higher scores indicating more illness insight. Possible Service Engagement Scale scores range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating lower engagement. Possible scores on the perceived coercion questionnaire range from 15 to 75, with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived coercion.)

Perceived benefit from involuntary hospitalization was assessed at the six- and 12-month follow-ups. Participants were asked, "Do you think you have benefited from your index court-ordered admission?" Answering options ranged from 5, disagree greatly, to 1, agree greatly, and included an answer of "don't know/neutral" (score of 3). Level of perceived benefit at 12 months was dichotomized into moderate or full perceived benefit (score of 1 to 2) versus neutral or no perceived benefit (score of 3 to 5).

SPSS for Windows, version 15.0, was used for correlations and logistic regression analyses. [Tables showing characteristics at baseline and correlations with perceived benefit and positive change in perceived benefit (defined as a negative or neutral response at the six-month follow-up and a positive response at the 12-month follow-up) are available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

Results

The sample consisted of 118 (68%) men and 56 (32%) women; the mean±SD age was 35±14 years. In line with findings from an earlier study on compulsory admission in Rotterdam (22), we found that most patients were of non-Dutch origin (N=101, 58%). Most patients were not married (N=127, 73%) and had a lower level of education (lower-secondary education: N=88, 51%). (Lower-secondary education is equivalent to seventh to tenth grade in the United States.) Twenty-one patients (12%) were homeless. Almost half of the patients had previously been hospitalized voluntarily (N=82, 47%). The mean length of hospitalization was 28±20 weeks. Most patients were involuntarily hospitalized because they were a danger to themselves (N=109, 63%); 65 (37%) were considered to be dangerous to others or to public safety. A majority of patients (N=138, 79%) had schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder. The average BPRS sum score at baseline was 58±12, and the mean GAF score at admission was 28±10, indicating a group of markedly ill patients. The mean score for illness insight was 12±6, and service engagement scores averaged 25±9, indicating a moderate impairment of insight and somewhat poor engagement with mental health services. At baseline, patients reported medium-high levels of perceived coercion (mean score of 55±12 on the perceived coercion questionnaire).

At the six-month follow-up, 75 patients (43%) reported that they had derived benefit from their commitment, 42 (24%) did not know or gave a neutral answer, and 57 (33%) felt they had not benefited. At the 12-month follow-up, we found modest improvement: 90 patients (52%) reported perceived benefit from their commitment. Twenty-two of the 99 patients (22%) who did not respond positively after six months reported at least some benefit at 12 months.

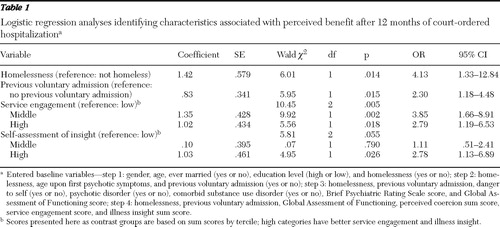

Results of logistic regression analyses identifying characteristics associated with perceived benefit are summarized in Table 1 . We included all candidate predictors that were significantly associated with perceived benefit at an alpha level of .10. Clinical characteristics were included in the regression model because psychotic disorder and symptom severity at baseline were correlated with an improved perception of benefit (Pearson's r=-.13 and -.18, respectively). The final regression model included homelessness, previous voluntary hospitalization, service engagement, and illness insight (Nagelkerke R 2 =.24; Hosmer-Lemeshow test χ2 =4.85, df=8, p>.10). Patients who reported perceived benefit were more likely to be homeless (odds ratio [OR]=4.13) or to have been previously hospitalized voluntarily (OR=2.30). Perceived benefit was also more likely to be reported by patients with a high level of service engagement (OR=2.79) or with more illness insight (OR=2.78). Sensitivity analyses were performed in which the neutral response category was moved to the moderate or full perceived benefit category, and similar patterns were seen.

|

Discussion

Preventing negative consequences of compulsory admission can help reduce the number of patients who are reluctant to accept treatment. This prospective study identified several predictors combining information on demographic, administrative, clinical, and psychosocial factors. All inpatient services in the area participated in the study, and all admissions were regulated by the same judicial procedures, thereby limiting confounding effects of specific admission policies and varying implementations of the judicial process. There was minimal loss to follow-up, even though this group of patients is often difficult to contact. However, a limitation of the study was the loss of nearly one-third of 403 patients because of the inclusion criteria or patients' refusal to participate. Although in most cases patients were excluded for logistical reasons, some patients actively hid from staff or escaped just after the court-ordered admission request had been issued. In addition, although refusal to participate in the study was relatively low (25%), selection bias could have occurred. Patients who are more reluctant to be in contact with mental health care might be in a worse mental state and have more negative views about compulsory admission. We also lacked data on additional types of compulsion that could mitigate patients' perspective on involuntary admission. However, perceived coercion as a subjective indicator of the use of compulsory measures did not independently contribute to perceived benefit.

Studies on perceived effects of compulsory admission are difficult to compare because of differences in design and study characteristics. These differences may account for inconsistencies in research outcomes. Kane and colleagues ( 4 ) found that more female patients evaluated the involuntary hospitalization as beneficial, and Beck and Golowka ( 2 ) reported that younger age predicted a perception of benefit. Effects of age or gender may have been confounded by service use or psychosocial factors not accounted for in studies with small samples. Other studies found no significant relationship between age, gender, or marital status and perceived benefit ( 3 , 5 ). In the study by Priebe and colleagues ( 6 ) perceived justification for involuntary hospitalization was related to living condition and satisfaction with treatment. In accordance with these findings, our study showed that homelessness and psychosocial factors—for example, service engagement and illness insight—were associated with perceived benefit. The living conditions of homeless patients before hospitalization were likely in sharp contrast to the structured setting of the psychiatric hospital. Previous voluntary admission was also associated with perceived benefit—this group of patients may have had a better understanding of the course of their illness and the circumstances in which compulsory admission is justified. In addition, service engagement and illness insight contributed to a perception of a positive benefit. These factors seem to reflect willingness and cognitive ability to create a working alliance between patients and staff that supports quality of care.

Bradford and colleagues ( 3 ) and Kjellin and colleagues ( 5 ) found no association between perceived benefit and types of symptom or diagnosis. Beck and Golowka ( 2 ) found that more patients with a diagnosis of either schizophrenia or affective disorders reported benefit. Priebe and colleagues ( 6 ) reported that patients with higher levels of functioning were less likely to view their involuntary admission as justified. We found no relationship between diagnosis or symptom level and perceived benefit one year after involuntary hospitalization, although clinical characteristics were related to a positive change in benefit perception between the six- and 12-month follow-up. These findings indicate that causality of associations needs further attention before effective intervention programs can be developed.

Conclusions

Twelve months after court-ordered admission about half the patients (52%) reported at least some benefit from involuntary hospitalization. Higher level of service engagement and illness insight were associated with more perceived benefit from involuntary hospitalization. After a request for involuntary commitment is issued, clinicians might focus more on strategies to improve psychosocial factors.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The study was carried out with the support of the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sports (ZonMw research grant 100-002-004). The authors thank all of the participating patients, caregivers, and medical and paramedical staff of Parnassia Bavo Group, Delta Psychiatric Center, Delfland Mental Health Center, and the Department of Psychiatry at Erasmus MC.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Katsakou C, Priebe S: Outcomes of involuntary hospital admission: a review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 114:65–71, 2006Google Scholar

2. Beck JC, Golowka EA: A study of enforced treatment in relation to Stone's "thank you" theory. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 6:559–566, 1988Google Scholar

3. Bradford B, McCann S, Merskey H: A survey of involuntary patients' attitudes towards their commitment. Psychiatric Journal of the University of Ottawa 11:163–165, 1986Google Scholar

4. Kane J, Quitkin F, Rifkin A, et al: Attitudinal changes of involuntarily committed patients following treatment. Archives of General Psychiatry 40:374–377, 1983Google Scholar

5. Kjellin L, Andersson K, Candefjord IL, et al: Ethical benefits and costs of coercion in short-term inpatient psychiatric care. Psychiatric Services 48:1567–1570, 1997Google Scholar

6. Priebe S, Katsakou C, Amos T, et al: Patients' views and readmissions 1 year after involuntary hospitalisation. British Journal of Psychiatry 194:49–54, 2009Google Scholar

7. Dressing H, Salize HJ: Compulsory admission of mentally ill patients in European Union Member States. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 39:797–803, 2004Google Scholar

8. Composite International Diagnostic Interview, Version 2.1 Auto. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1997Google Scholar

9. Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J: Manual for expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): Appendix A. Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:594–602, 1986Google Scholar

10. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799–812, 1962Google Scholar

11. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, Text Revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

12. Kemp R, David A: Insight and compliance; in Treatment Compliance and the Therapeutic Alliance in Serious Mental Illness. Edited by Blackwell B. Newark, NJ, Harwood Academic Publishers, 1997Google Scholar

13. Sanz M, Constable G, Lopez-Ibor I, et al: A comparative study of insight scales and their relationship to psychopathological and clinical variables. Psychological Medicine 28:437–446, 1998Google Scholar

14. Tait L, Birchwood M, Trower P: A new scale (SES) to measure engagement with community mental health services. Journal of Mental Health 11:191–198, 2002Google Scholar

15. Gardner W, Hoge SK, Bennett N, et al: Two scales for measuring patients' perceptions of coercion during mental hospital admission. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 11:307–321, 1993Google Scholar