Program Characteristics Associated With Testing for HIV and Hepatitis C in Veterans Substance Use Disorder Clinics

HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections are leading causes of death and disability in the United States. Much of the morbidity and mortality from these conditions is due to late detection and late entry into care ( 1 , 2 ), which could be addressed by more widespread screening and testing. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest provider of HIV and HCV care in the United States. Despite efforts to increase testing among veterans ( 3 , 4 ), rates of HIV and HCV testing remain suboptimal, even among those with known risk factors. Substance use disorders increase the risk of infection by HCV ( 5 ) and HIV ( 6 , 7 ). Despite this increased risk, a recent study in the Pacific Northwest found that only 19% of VA patients with substance use disorders had been tested for HIV and only 60% had been tested for HCV ( 8 ).

Beginning in 1999 the VA mandated its health facilities to conduct universal screening for HCV risk factors (and to conduct antibody testing if risk factors were present), created a computerized clinical reminder in the electronic medical record, which prompts providers to screen and test their patients for HCV, and made HCV risk screening a quality performance measure ( 3 ). The VA has also devoted resources to increasing HIV screening rates ( 4 ). Recent research has shown that quality improvement initiatives such as provider feedback and provider activation can increase HIV testing rates among at-risk patients ( 4 ). Little is known, however, about how these policies and characteristics of substance use disorder programs may affect infectious disease testing rates in substance use disorder programs.

The Drug and Alcohol Program Survey (DAPS) collects data about the VA's substance use disorder programs, which treat over 120,000 patients annually. In 2006 all VA substance use disorder clinics (N=232) responded to the DAPS survey, which for the first time included questions about HIV and HCV testing and about system-level initiatives to increase testing rates (for example, computerized reminders and provider feedback). We describe HIV and HCV testing rates by substance use disorder program type. We also evaluate whether quality improvement systems are related to HIV and HCV testing rates.

Methods

We surveyed every VA program that was designed to treat patients who have substance use disorders, had at least two full-time staff, and could be distinguished from other programs on the basis of unique staffing, patients, clinical services, or policies. The survey response rate was 100% (N=232). Of these, nine programs did not meet the above inclusion criteria, resulting in 223 programs in our analyses.

The survey was mandated in all VA substance use disorder programs, was conducted between October 1, 2006, and January 31, 2007, and was completed by the substance use disorder program director or designee. It covered patient characteristics, treatments, staffing, continuity of care, HIV and HCV screening and testing, and quality improvement systems in use. For most items, respondents were asked to describe programs and characteristics in place during September 2006. Program directors were asked about services directly delivered within their substance use disorder programs. Information gathered included the outcome measures of the percentage of clinic patients who, between October 1, 2005, and September 30, 2006, received HIV testing and HCV testing from program staff. We combined conceptually related items into indices.

The six quality improvement systems assessed were provider education, computerized reminders, computerized templates to guide test orders, provider performance profiling and feedback, presence of a clinical champion to promote and monitor the progress of testing, and presence of a designated clinician for testing. All of these variables were dichotomous. They were selected because they are commonly used quality improvement methods that have been used to increase infectious disease testing ( 4 , 9 , 10 ).

Treatments and services provided in the substance use disorder programs were assessed through two variables. Supplementary services referred to smoking cessation and vocational training, and the variable was calculated by summing the percentages of patients engaged in a smoking cessation program or in vocational training and then dichotomizing at the median (a code of 1 indicated more patients receiving services). Evidence-based medication therapy was a dichotomous variable, where 1 indicated use of any of five treatments (methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone for opioid use, and naltrexone or acamprosate for alcohol use) and 0 indicated that none of these treatments were used.

Six variables described program characteristics, such as program type (such as inpatient or residential), staffing, patients, and emphasis on infectious disease testing. The priority a clinic places on infectious disease testing was assessed by asking respondents to compare HIV testing (for the first regression model) and HCV testing (for the second regression model) with the "assessment and treatment of other common conditions (mental health care, diabetes monitoring, cancer screening, chronic pain management)," scored as 0, not important; 1, somewhat important; and 2, very important. Substance use disorder programs were uniquely assigned to one category according to type of treatment and services they provided ( 11 ). Inpatient programs provided 24-hour acute care. Residential programs provided round-the-clock care but without 24-hour medical staff. Intensive outpatient programs provided at least three hours of programming three days per week, and standard outpatient programs (the reference category in multivariate models) provided care that did not meet the frequency criteria of intensive treatment for outpatients. All programs provided psychosocial rehabilitation.

Medical staff was assessed by the number of physicians, physician assistants, and nurses divided by total staff and then dichotomized at the median; social welfare staff was quantified as the sum of psychologists, social workers, addiction therapists, and psychiatric technicians or aides divided by total staff and then dichotomized at the median (with 1 indicating more staff). Number of unique patients represented patients admitted to the program during the 2006 fiscal year. Patients with complex needs represented five summed variables—percentages of patients who were homeless (or in unstable living arrangements), nicotine dependent, opioid dependent, or not married (or in a long-term relationship) or who had a major psychiatric disorder, with results dichotomized at the median (with 1 indicating more patients with complex needs).

Descriptive statistics were estimated for total respondents and for each program type (inpatient, residential, intensive outpatient, or standard outpatient). We compared program types by organizational characteristics by using analysis of variance and chi square tests. Next, we estimated differences in the use of quality improvement systems for HIV testing versus HCV testing using chi square tests.

Multivariate regression analyses were conducted with HIV and HCV testing rates as the dependent variables. In the models, we retained variables that in bivariate analyses were significantly associated (p≤.05) with either HIV testing or HCV testing. In addition, despite bivariate nonsignificance, for conceptual reasons we retained clinical champion, inpatient program, intensive outpatient program, and number of patients in multivariate models. We examined interactions between designated clinician for screening and medical staffing levels, between designated clinician for screening and number of patients, and between evidence-based medication treatments and medical staffing levels. We conducted sensitivity analyses to see whether our results differed when the outcome variables (HIV and HCV testing rates) were dichotomous instead of continuous. We used three cut points for dichotomization: 75%, 50%, and 25% of patients tested. This study was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board and Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System Research and Development Committee.

Results

In all programs combined (N=223), mean±SD reported testing rates were lower for HIV (35%±40% of patients in the program, median 10%) than for HCV (57%±44%, median 80%) (t=8.61, df=222, p<.001 for difference of means). Residential programs (N=65) reported testing the largest proportion of patients for HIV and HCV. For HIV, residential programs tested 51%±44% of patients, versus 23%±35% for outpatient programs (N=97) (F=6.52, df=3 and 219, p<.001). For HCV, residential programs tested 73%±39% of patients, versus 45%±45% for outpatient programs (F=5.63, df=3 and 219, p=.001). Inpatient programs (N=19) tested 40%±42% and 63%±43% of patients, on average, for HIV and HCV, respectively, whereas intensive outpatient programs (N=42) tested 36%±39% and 55%±44% of patients, respectively. About one-third of programs (N=77 or 35%) tested more than half of their patients for HIV, 131 programs (59%) tested more than half for HCV, and 74 programs (33%) tested more than half of their patients for both HIV and HCV. The Pearson correlation between HIV and HCV testing was .61 (p<.01). Residential programs, compared with the other types of program, rated the importance of HIV testing (F=5.29, df=3 and 217, p=.002) and HCV testing (F=4.75, df=3 and 216, p=.003) highest compared with testing for other conditions, and outpatient and inpatient programs rated the importance of HIV and HCV testing lowest.

On average, of the quality improvement systems, programs used computerized reminders most frequently (91 programs, 41%, for HIV and 164 programs, 74%, for HCV) ( χ2 =22.28, df=1, p<.01), followed by provider education (122 programs, 55%, for HIV versus 131 programs, 59%, for HCV), computerized templates (92 programs, 41%, for HIV versus 106 programs, 48%, for HCV), designated clinician for testing (78 programs, 35%, for HIV versus 84 programs, 38%, for HCV), performance profiling (32 programs, 14%, for HIV versus 41 programs, 18%, for HCV), and clinical champion for testing (19 programs, 9%, for HIV versus 34 programs, 15%, for HCV). These systems were used more for HCV than for HIV, although the difference was significant for computerized reminders only.

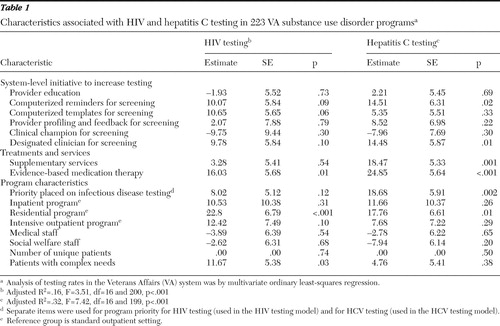

Results of multivariate models are shown in Table 1 . Computerized templates were positively associated with HIV testing, although the association was not quite significant (p=.06). For HCV testing, use of computerized reminders (p=.02) and use of a designated clinician for screening (p=.01) were significant. Provision of supplementary services (smoking cessation services and vocational training) was positively associated with HCV testing (p=.001), and use of evidence-based medication therapy was positively associated with both HIV testing (p=.01) and HCV testing (p<.001). Among program characteristics, priority placed on infectious disease testing was significantly associated with HCV testing (p=.002), residential programs (compared with standard outpatient programs) were more likely to test for both HIV (p<.001) and HCV (p=.01), and the variable patients with complex needs was positively associated with HIV testing (p=.03). None of the interactions we examined (between designated clinician and medical staffing levels, between designated clinician and number of patients, and between evidence-based medication treatments and medical staffing levels) were statistically significant. Our sensitivity analyses with dichotomous outcome variables produced substantially the same results as with continuous outcomes.

|

Discussion

In the first nationwide survey of HIV and HCV testing in VA substance use disorder programs, 223 program directors reported testing, on average, 35% of patients for HIV and 57% for HCV. The highest rates of testing were in residential programs (51% for HIV and 73% for HCV), and the lowest rates were in standard outpatient programs (23% for HIV and 45% for HCV). Computerized templates to guide test orders were associated with higher reported HIV testing rates, although the relationship did not achieve statistical significance (p=.06). Computerized reminders and designated clinician for screening were associated with higher reported HCV testing rates. There was substantial variation in the use of the quality improvement systems, ranging from computerized reminders used by 91 (41%) and 164 (74%) programs, respectively for HIV and HCV testing, to clinical champions for testing used by 19 (9%) and 34 (15%) programs, respectively.

Reported testing rates for both HIV and HCV are strikingly low, especially given that patients with substance use disorders are at high risk for both conditions and that guidelines supporting testing of these groups are widely endorsed and disseminated. There are several possible explanations for low testing rates. Providers with many demands may focus on their immediate job of treating substance use disorders. Especially with opioid-dependent patients, providers may feel a sense of urgency to stabilize their patients above all else, in order to prevent relapse and possible death from overdose. Other providers may not be aware of the importance of viral screening. Also, patients' refusal of testing could contribute to low testing rates.

The 22% gap we found between mean reported HIV and HCV testing rates may reflect HIV testing policies in the VA at the time that made HIV testing more of a clinical burden than other blood tests by requiring written informed consent and pre- and posttest counseling. Also, until recently, VA policy strongly emphasized HCV testing by mandating computerized clinical HCV testing reminders. Also, the greater prevalence of HCV infection among veterans may lead to greater provider awareness and higher priority for HCV testing and treatment. The positive association between percentage of patients with complex needs and HIV testing rates may similarly reflect greater interest in infectious disease screening when clinicians and managers perceive, on the basis of patient characteristics, that HIV prevalence may be high in their patient population.

Of interest is that use of evidence-based medication therapies for opioid and alcohol use was significantly associated with both HIV and HCV testing rates. We suspect that programs using evidence-based medication therapies are more medically (versus behaviorally) oriented and thus may order more medical diagnostic tests, such as those for HIV and HCV. Also noteworthy, computerized templates were positively associated with only HIV testing, whereas computerized reminders were significantly associated with only HCV testing. The former may indicate that computerized templates were well suited for HIV testing in the VA because of the multiple steps and forms required when we conducted our survey (the process in the VA has been streamlined since then), and the latter may reflect the VA's implementation of the HCV testing reminder in the electronic medical record ( 3 ). The association of a designated clinician for HCV screening may indicate that providers are more likely to order tests if they know that a responsible clinician will ensure their implementation.

Our study has several limitations. Data were collected cross-sectionally, which limits our ability to make causal inferences. We used reports from program directors to assess HCV and HIV testing rates. The rates we observed may be subject to reporting bias (such as inflated estimates). Our findings for HIV testing, however, are similar to recent, separate analyses of VA administrative data that suggest that about 28% of veterans treated in substance use disorder programs receive HIV testing ( 12 ). Thus it is likely that the rates of testing shown here, although generally low, may have been even lower if we used different methods. Our independent variables were also based on respondent report and were not independently verified. It is important to note, however, that substance use disorder programs are the only repository of information about services and testing provided to patients in those programs. VA administrative data structures do not allow unambiguous matching of patients to specific substance use disorder programs. Thus this survey represented the most efficient means of examining system-level issues in substance use disorder programs and enabled the comparison of program-level testing rates with program-level characteristics, such as services provided and staffing levels.

Conclusions

Despite limitations, these national survey results suggest strikingly low rates of testing in VA substance use disorder programs, with 35% of patients tested for HIV and 57% tested for HCV. The gap between the rates may reflect differences in VA policies (at the time of the survey, written informed consent was required for HIV testing) or greater awareness, among providers, of HCV because of its higher prevalence. Our finding of an association between quality improvement systems and higher testing rates is encouraging for substance use disorder programs interested in increasing testing rates. Most promising were computerized templates for HIV testing and computerized reminders and designated clinicians for HCV testing.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative HIV/hepatitis C; VA Bedford Center for Health Quality, Outcomes and Economic Research; VA Palo Alto Center for Health Care Evaluation; and the VA Palo Alto National Center for PTSD.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Mallette C, Flynn MA, Promrat K: Outcome of screening for hepatitis C virus infection based on risk factors. American Journal of Gastroenterology 103:131–137, 2008Google Scholar

2. Caring for Veterans With HIV Disease: Characteristics of Veterans in VA Care. Washington, DC, US Department of Veterans Affairs, Public Health Strategic Health Care Group, Center for Quality Management in Public Health, 2003Google Scholar

3. Huckans MS, Blackwell AD, Harms TA, et al: Management of hepatitis C disease among VA patients with schizophrenia and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services 57:403–406, 2006Google Scholar

4. Goetz MB, Bowman C, Hoang T, et al: Implementing and evaluating a regional strategy to improve testing rates in VA patients at risk for HIV utilizing the QUERI process as a guiding framework. Implementation Science 3:16, 2008Google Scholar

5. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: management of hepatitis C. Hepatology 36:S3–S20, 2002Google Scholar

6. Rees V, Saitz R, Horton NJ, et al: Association of alcohol consumption with HIV sex- and drug-risk behaviors among drug users. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 21:129–134, 2001Google Scholar

7. Strathdee SA, Sherman SG: The role of sexual transmission of HIV infection among injection and non-injection drug users. Journal of Urban Health 80:iii,7–14, 2003Google Scholar

8. Huckans MS, Blackwell AD, Harms TA, et al: Integrated hepatitis C virus treatment: addressing comorbid substance use disorders and HIV infection. AIDS 19:S106–S115, 2005Google Scholar

9. Renders CM, Valk GD, Griffin S, et al: Interventions to improve the management of diabetes mellitus in primary care, outpatient and community settings. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4:CD001481, 2001Google Scholar

10. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, et al: Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Affairs 20(6): 64–78, 2001Google Scholar

11. Tracy SW, Trafton JA, Humphreys K: The Department of Veterans Affairs Substance Abuse Treatment System: Results of the 2003 DAPS. Washington, DC, US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2004Google Scholar

12. Dookeran NM, Burgess JF, Bowman C, et al: HIV screening among substance abusing veterans in care. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 37:286–291, 2009Google Scholar