Trends in Mental Health Admissions to Nursing Homes, 1999–2005

Mental illness is common among nursing home residents. The high prevalence of dementia among residents is well known, but major mental illness other than dementia is also common. Indeed, an estimated 560,000 nursing home residents in 2002 had a mental illness other than dementia—a number that dwarfs the 51,000 ( 1 ) individuals in beds at psychiatric hospitals in that year. Mental illness is one factor—and sometimes the decisive factor—contributing to nursing home placement ( 2 ). Addressing the needs of nursing home residents with behavioral symptoms associated with dementia, such as decreasing the rate of use of physical and chemical restraints, has been a principal focus of research in nursing homes ( 3 , 4 ). However, less is known about individuals in nursing homes who have major mental illness.

Estimates of the rate of significant depressive symptoms among nursing home residents range from 10% to 44% ( 5 , 6 , 7 ). Estimates of the prevalence of schizophrenia in nursing homes range from 4% to 13% ( 8 , 9 ). Among persons with mental illness, a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder was found to be associated with a greater likelihood of admission to a nursing home over a three-year period ( 10 ), and depression was shown to increase the risk of nursing home admission of elderly persons both from the community and after an acute hospitalization ( 11 , 12 , 13 ). Depression and behavioral symptoms among nursing home residents are associated with high rates of functional impairment, disability, poor health outcomes, increased rates of hospitalization and mortality, and greater emergency service use ( 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ). High rates of comorbid general medical conditions, deficits in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living, cognitive impairment, and lack of available family members predict admission to nursing homes among older adults with mental illness ( 19 , 20 ).

The nursing home sector has undergone a remarkable transformation over the past two decades with respect to payers and patient mix. Until the early 1980s, nursing homes largely provided custodial care to long-stay residents. The short-stay, postacute side of the nursing home market was negligible. Medicare, the primary payer for postacute services, accounted for only 1.6% of total nursing home expenditures in 1980 ( 21 ). A series of policy changes, however, expanded the postacute side of the market. By 2006 Medicare accounted for 15.7% of all nursing home expenditures. Further, federal standards for Medicaid reimbursement were repealed, and social work services were bundled into the nursing home's per diem rate. Growth in the population of short-stay nursing home residents and decreased reimbursement for social work may have led to important changes in the relative proportions of nursing home residents admitted with mental illness and dementia.

Little is known about recent trends in admission of individuals with mental illness to nursing homes. This observational study used longitudinal data on the census of new nursing home admissions to describe trends in mental illness. We regard this as a first step in directing research and policy attention to the largest population of vulnerable persons with mental illness in institutionalized settings. More specifically, we examined admissions to nursing homes from 1999 to 2005 of individuals diagnosed as having mental illness, dementia, or both. We compared the demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and treatment of individuals with and without mental illness.

Methods

Data

We used the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) national registry of nursing home resident assessments from the Minimum Data Set (MDS) to examine the prevalence of mental illness among new nursing home admissions. The MDS resident assessment instrument contains nearly 400 data elements, including cognitive functioning, physical functioning, psychosocial well-being, diagnoses, and treatment variables. In describing annual trends, we examined all first-time admissions from 1999 to 2005 (N=7,364,470) and short-stay and long-stay admissions from 1999 to 2004 (N=6,368,159). We used 2005 data (996,311 first-time admissions) to examine demographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, and treatments received. Institutional review board permission was obtained for this study from Brown University.

Measures

Mental illness diagnosis. We used the MDS full assessment form to identify a behavioral health diagnosis on admission. We grouped individuals into four overall categories: mental illness only (section I1dd, I1ee, I1ff, or I1gg indicated on admission MDS), dementia only (including Alzheimer's and other dementia) (section I1q or I1u indicated), both mental illness and dementia, and neither. Mental illness only was further categorized into four hierarchical categories: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and anxiety disorders (in this order). For example, an individual with a diagnosis of both schizophrenia and an anxiety disorder was categorized in the schizophrenia group. Because the MDS does not include the primary reason for admission, a mental illness diagnosis can represent either the primary reason for admission or a comorbid condition.

Demographic characteristics, comorbidity, and mental health treatment. Age, sex, race-ethnicity, marital status, and educational status are documented on the MDS full assessment form. We categorized race-ethnicity as white, black, Hispanic, and other (American Indian or Alaskan Native and Asian or Pacific Islander). Marital status was classified as never married, married, widowed, and separated or divorced. Educational status was categorized as less than high school (no schooling, grade 8 or less, and grades 9 to 11), graduated from high school (a high school, technical school, or trade school, and possibly some college), graduated from college, graduate degree, or unknown (not reported). We identified the following comorbid conditions: diabetes, other endocrine, cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, neurological excluding dementia, pulmonary, sensory, and other diseases.

Limitations in activities of daily living were calculated with use of a scale ranging from 0 to 28, with higher values indicating greater disability. We used CMS's definition of cognitive impairment as having impaired short-term memory (MDS item B2a=1) and not being independent in regard to daily decision making (MDS item B4<0). Treatment variables included both medication treatment and other treatments provided within the past seven or 14 days. Medication treatment variables included average number of medications and any receipt of antipsychotics, antidepressants, or anxiolytics-hypnotics in the past seven days. Other treatments consisted of residence in an Alzheimer's and dementia special care unit (in the past 14 days), receipt of skills training to return to the community (in the past 14 days), and evaluation or treatment by a mental health specialist (in the past seven days). We also examined episodes of restraint (in the past seven days).

Short stay versus long stay. We followed the method of Mor and colleagues ( 22 ) to categorize length of stay. Residents discharged within 90 days were categorized as short-stay residents. Those who remained in the nursing home at least 90 days were categorized as long-stay residents.

Analysis

We examined overall trends from 1999 to 2005 in the number of persons admitted with mental illness, dementia, or both in short-stay and long-stay populations. We calculated overall prevalence rates of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and anxiety disorders among individuals admitted to nursing homes during this period. We describe the demographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, and treatments by mental illness category. Statistical comparisons for categorical variables were made with an overall chi square test.

Results

In 2005 the number of persons with a mental illness newly admitted to a nursing home exceeded the number with dementia. Of the 996,311 persons newly admitted to U.S. nursing homes in 2005, 19% (N=187,478) were admitted with mental illness only, 12% (N=118,290) had dementia only, 6% (N=64,669) had both a mental illness and dementia, and 63% (N=625,874) had neither mental illness nor dementia.

The relative proportions of persons newly admitted to nursing homes with mental illness and dementia, as well as the absolute number, reflect important changes over recent years ( Figure 1 ). In 1999 the number of new admissions with dementia exceeded the number with mental illness. By 2005 the number with mental illness exceeded the number with dementia. Residents admitted with mental illness increased from 168,721 in 1999 to 187,478 in 2005, and the number admitted with dementia fell from 208,505 to 118,290. The percentage of individuals admitted with both mental illness and dementia was roughly constant.

In 1999 long-stay residents accounted for 38.5% of all nursing home admissions. By 2005 this proportion was 25.3%. Trends similar to those described above can be seen among both short-stay and long-stay residents ( Figure 1 ). As expected, the percentage of residents admitted with dementia only was higher in the long-stay population. From 1999 to 2004, the proportion of residents admitted with only dementia decreased in both the short-stay population (by 4.4 percentage points) and the long-stay population (by 3.4 percentage points). In contrast, the proportion of residents admitted with only mental illness increased in both the short-stay population (by 4.7 percentage points) and the long-stay population (by 3.2 percentage points). In both cases, the trends were stronger in the short-stay population. Finally, the proportion of residents admitted with both dementia and mental illness increased in the long-stay population (by 3.8 percentage points).

Between 1999 and 2005 the number of individuals admitted with depression increased 4.5 percentage points, from 11.0% (N=128,566) to 15.5% (N=154,262) ( Figure 2 ). Over the same period, there was a .1 percentage point increase in residents admitted with bipolar disorder, from .4% (N=4,597) to .5% (N=5,299). Admissions of residents with an anxiety disorder declined by .2 percentage points, from 2.5% (N=29,221) to 2.3% (N=22,513). The percentage of newly admitted residents with schizophrenia remained roughly constant at .5%. Thus the large increase in admissions of persons with mental illness from 1999 to 2005 was primarily due to the increase in residents with a diagnosis of depression.

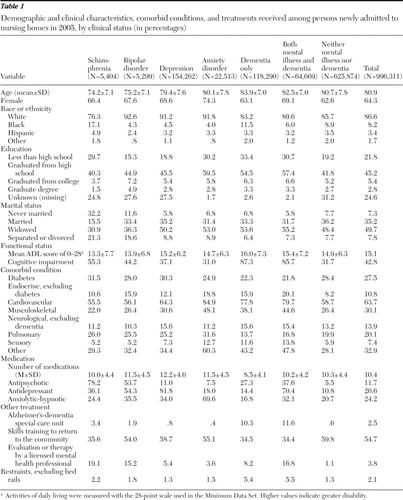

As shown in Table 1 , individuals admitted with mental illness or dementia differed from other nursing home residents (and from one another) in their demographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, and treatments received. Compared with those who had neither mental illness nor dementia, those with a mental illness were generally younger and white (except for those with schizophrenia). Those admitted with schizophrenia, an anxiety disorder, or dementia were more poorly educated, and those with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were less likely to be married. Individuals admitted with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder had lower activities of daily living scores and higher levels of cognitive impairment than those with depression, an anxiety disorder, or neither mental illness nor dementia.

|

Individuals with anxiety, depression, or dementia were more likely to have cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, or neurological comorbidities. Individuals in each category of mental illness were more likely to have pulmonary disease than those with dementia and those without dementia or mental illness. Individuals with schizophrenia or dementia were on fewer medications than those with other mental illnesses and those without dementia or mental illness. As expected, individuals with depression had higher rates of antidepressant treatment. Individuals with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, and to a lesser extent those with dementia, had higher rates of antipsychotic use. Those with an anxiety disorder had higher rates of anxiolytic-hypnotic use. Those with schizophrenia and dementia were less likely than those with bipolar disorder, depression, or an anxiety disorder to receive training in skills required to return to the community and more likely to be physically or chemically restrained. Finally, those with mental illness or dementia were more likely to receive evaluation or therapy by a licensed mental health professional than those without mental illness or dementia.

Because of the substantial increase over time in individuals admitted with depression, we examined demographic, clinical, and treatment variables for 1999 and for 2005. Age, gender, and racial-ethnic make-up of new admissions with depression were largely the same. An increase was found in the proportion of depressed individuals who were married (31.7% to 35.2%), and a decrease was noted in the proportion who were widowed (55.1% to 50.2%). Functional status was similar. With the exception of diabetes and lung disease, both of which increased, all other comorbid conditions decreased from 1999 to 2005. In 2005 individuals were taking more medications than in 1999 (12.2 compared with 10.4 medications); a greater proportion used psychotropic medications (antipsychotics, 11.0% in 2005 and 8.3% in 1999; antidepressants, 81.8% and 77.8%; and anxiolytics, 34.0% and 32.5%); and they experienced fewer episodes of restraint (1.3 and 2.4). Finally, a larger percentage of depressed residents received skills training to return to the community in 2005 (58.7% compared with 41.8% in 1999), and a smaller proportion were evaluated by a mental health professional in 2005 (5.4% compared with 10.4%). Given the large numbers involved, all overall differences were statistically significant at a p<.001 level.

Discussion

Between 1999 and 2005, admissions to nursing homes of individuals with dementia decreased and admissions of individuals without dementia who had a mental illness, primarily depression, increased. As expected, those admitted with mental illness or dementia differed from one another and from other nursing home residents in demographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, and treatments received.

These findings raise two important questions. First, what factors account for the change in mix of admissions? And second, what does this new mix of patients imply for nursing homes and the treatment of persons with mental illness?

One explanation for the decrease of admissions with dementia (and the increase in admissions with depression) is the growth in postacute, short-stay nursing home residents. Individuals with dementia are more likely to be admitted for long-stay placement, and nursing homes have increasingly shifted away from the long-stay population. Higher payments for postacute stays by Medicare and to lower payments by Medicaid for long-term care contribute to this shift. A second factor is the increased development of alternatives to nursing homes for individuals with dementia. In particular, assisted living facilities and increased home support for individuals with dementia have attracted some away from nursing homes ( 23 , 24 ).

The number of individuals admitted with depression (either as a primary or secondary diagnosis) increased markedly from 1999 to 2005. Studies have shown increases in the diagnosis of depression among community-dwelling elderly persons during the 1990s. Crystal and colleagues ( 25 ) found that the percentage of elderly Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed as having depression increased from 2.8% in 1992 to 5.8% in 1998 ( 25 ). Follow-up studies found that this increase was consistent with the use of new treatment modalities, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors ( 25 , 26 , 27 ). Increased rates of either recognition or prevalence could explain observed increases in the number of persons admitted with depression.

The numbers of elderly individuals admitted to nursing homes with serious mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, has remained roughly constant. Medicaid waivers for developing home- and community-based services for individuals with mental illness have been negligible ( 28 ). Studies have shown that cognitive impairment, limitations in activities of daily living, and social isolation place individuals at risk both of being admitted to a nursing home and of becoming long-stay residents ( 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ). Individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder have high rates of cognitive impairment and social isolation, as we found in this study, which places them at greater risk of nursing home admission.

What are the implications for nursing homes and for treatment of this new mix of patients? Nursing homes are coping with a large influx of postacute patients with comorbid depression. The effects of depression on nursing home use, hospital readmission from nursing homes, and reintegration into the community of nursing home residents are questions that have only begun to be explored. Studies have shown that depression places elderly individuals hospitalized for stroke at higher risk of nursing home placement; depression prolongs nursing home care and increases costs in acute and rehabilitation services; and depression increases the risk of rehospitalization among elderly persons ( 33 , 34 , 35 ). In addition, the increased morbidity often associated with depression, which can lead to poor medication compliance, poor self-care, and increased mortality, places individuals with depression at greater risk of requiring nursing home care ( 12 , 13 ). Whether or not more intensive treatment of depression can improve outcomes for elderly nursing home residents is unknown.

Given these issues, a key concern is the quality of care received by individuals with a mental illness in nursing homes. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 was the most recent major policy reform directly addressing the need for appropriate mental health services in nursing homes. These regulations mandated a Pre-Admission Screening and Annual Resident Review to identify nursing home residents with a history of mental illness. However, studies have reported low rates of implementation of recommended mental health services ( 36 , 37 ). One study found that only 35% of preadmission screening recommendations for new mental health services were followed ( 38 ). A study conducted in 1997 found that among nursing home residents with an identified psychiatric diagnosis, only 36% received a mental health visit during that year ( 39 ). More recent data indicate that approximately one-fifth of all nursing homes receive a deficiency citation each year for mental health care as part of the federal survey and certification process ( 40 , 41 ).

The MDS data have limitations. The MDS depends on accurate recording of information by assessment nurses, including diagnoses. Studies have generally confirmed the reliability and validity of these data, with some variability across nursing homes ( 42 ). A recent examination shows that rates of diagnosis of mental illness are higher in the MDS (46%) than in a cross-sectional analysis of data from the National Nursing Home Survey (33.1%) ( 43 ). Unlike a standard diagnostic interview, the recorded diagnosis is not a validated method for assigning a diagnosis. This may lead to misclassification of individuals as having or not having depression. Both diagnostic biases should be systematic over time; however, it is possible that the trends reported here result from an increase in these biases over time.

Further, we were not able to verify diagnosis, treatment, or functional measures from outside sources. The linkage of the MDS to other data sources (for example, claims data) would help to address this limitation. However, the fact that the medication patterns largely supported the disease classifications is reassuring. Finally, our sample represented first-time nursing home admissions rather than a cross-section of residents at a given point each year. As such, our data reflect the flow of residents into nursing homes but not the resident population that remains over time.

Conclusions

Over the past decade the mix of patients with mental illness and dementia in nursing homes has changed. The number of admissions of patients with dementia has fallen dramatically, and the number admitted with mental illness, particularly depression, has increased. Given the high rates of comorbidity and mixed treatment success in nursing homes, increased focus should be placed on understanding the role played by mental illness in nursing home placement and the quality and cost of care for these nursing home residents. In particular, research that focuses on understanding the impact of depression and depression treatment on nursing home costs, community reintegration, and hospital readmissions will be particularly important as the rates of depression in postacute care nursing homes increase.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Dr. Fullerton was supported in part by grant 5T32-MH019733 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Dr. McGuire was supported by grant P60-MD002261 from the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities and NIMH grant P50 MH073469. Dr. Feng and Dr. Mor were supported in part by grant R01-AG26465 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA), which also supported the data use agreement for this work (DUA 15293). Dr. Grabowski was supported in part by NIA career development award K01-AG024403.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Frank RG, Glied SA: Better but Not Well: Mental Health Policy in the United States Since 1950. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006Google Scholar

2. Black BS, Rabins PV, German PS: Predictors of nursing home placement among elderly public housing residents. Gerontologist 39:559–568, 1999Google Scholar

3. Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB, et al: Estimating prognosis for nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA 291:2734–2740, 2004Google Scholar

4. Phillips CD, Spry KM, Sloane PD, et al: Use of physical restraints and psychotropic medications in Alzheimer special care units in nursing homes. American Journal of Public Health 90:92–96, 2000Google Scholar

5. Devanand DP, Jacobs DM, Tang MX, et al: The course of psychopathologic features in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:257–263, 1997Google Scholar

6. Burrows AB, Satlin A, Salzman C, et al: Depression in a long-term care facility: clinical features and discordance between nursing assessment and patient interviews. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 43:1118–1122, 1995Google Scholar

7. Lyketsos CG, Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, et al: Mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: findings from the Cache County Study on Memory in Aging. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:708–714, 2000Google Scholar

8. Mechanic D, McAlpine DD: Use of nursing homes in the care of persons with severe mental illness: 1985–1995. Psychiatric Services 51:354–358, 2000Google Scholar

9. McCarthy JF, Blow FC, Kales HC: Disruptive behaviors in Veterans Affairs nursing home residents: how different are residents with serious mental illness? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52:2031–2038, 2004Google Scholar

10. Miller EA, Rosenheck RA: Risk of nursing home admission in association with mental illness nationally in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Medical Care 44:343–351, 2006Google Scholar

11. Onder G, Liperoti R, Soldato M, et al: Depression and risk of nursing home admission among older adults in home care in Europe: results from the Aged in Home Care (AdHOC) study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 68:1392–1398, 2007Google Scholar

12. Harris Y: Depression as a risk factor for nursing home admission among older individuals. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 8:271, 2007Google Scholar

13. Harris Y, Cooper JK: Depressive symptoms in older people predict nursing home admission. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 54:593–597, 2006Google Scholar

14. Gates DM, Fitzwater E, Meyer U: Violence against caregivers in nursing homes: expected, tolerated, and accepted. Journal of Gerontological Nursing 25:12–22, 1999Google Scholar

15. Forsell Y, Winblad B: Major depression in a population of demented and nondemented older people: prevalence and correlates. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 46:27–30, 1998Google Scholar

16. Kales HC, Blow FC, Copeland LA, et al: Health care utilization by older patients with coexisting dementia and depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:550–556, 1999Google Scholar

17. Clyburn LD, Stones MJ, Hadjistavropoulos T, et al: Predicting caregiver burden and depression in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Gerontology B: Psychological Science and Social Science 55:S2–S13, 2000Google Scholar

18. Bartels SJ, Horn SD, Smouth RJ, et al: Agitation and depression in frail nursing home elderly patients with dementia: treatment characteristics and service use. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 11:231–238, 2003Google Scholar

19. Bartels SJ, Mueser KT, Miles KM: A comparative study of elderly patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in nursing homes and the community. Schizophrenia Research 27:181–190, 1997Google Scholar

20. Kilbourne AM, Cornelius JR, Han X, et al: General-medical conditions in older patients with serious mental illness. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 13:250–254, 2005Google Scholar

21. Health, United States, 2007, With Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, 2007Google Scholar

22. Mor V, Zinn J, Gozalo P, et al: Prospects for transferring nursing home residents to the community. Health Affairs 26:1762–1771, 2007Google Scholar

23. Leon J, Moyer D: Potential cost savings in residential care for Alzheimer's disease patients. Gerontologist 39:440–449, 1999Google Scholar

24. Kopetz S, Steele CD, Brandt J, et al: Characteristics and outcomes of dementia residents in an assisted living facility. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 15:586–593, 2000Google Scholar

25. Crystal S, Sambamoorthi U, Walkup JT, et al: Diagnosis and treatment of depression in the elderly Medicare population: predictors, disparities, and trends. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 51:1718–1728, 2003Google Scholar

26. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, et al: National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA 287:203–209, 2002Google Scholar

27. Sambamoorthi U, Olfson M, Walkup JT, et al: Diffusion of new generation antidepressant treatment among elderly diagnosed with depression. Medical Care 41:180–194, 2003Google Scholar

28. Shirk C: Rebalancing Long-Term Care: The Role of the Medicaid HCBS Waiver Program. Washington, DC, National Health Policy Forum, 2006Google Scholar

29. Reschovsky JD: The demand for post-acute and chronic care nursing in nursing homes. Medical Care 36:475–490, 1998Google Scholar

30. Coughlin TA, McBride TD, Liu K: Determinants of transitory and permanent nursing home admissions. Medical Care 28:616–631, 1990Google Scholar

31. Liu K, McBride TD, Coughlin TA: Risk of entering nursing homes for long versus short stays. Medical Care 32:315–327, 1994Google Scholar

32. Greene V, Ondrich J: Risk factors for nursing home admissions and exits: a discrete-time hazard function approach. Journal of Gerontology 45:S250–S258, 1990Google Scholar

33. Nuyen J, Spreeuwenberg PM, Groenewegen PP, et al: Impact of preexisting depression on length of stay and discharge destination among patients hospitalized for acute stroke: linked register-based study. Stroke 39:132–138, 2008Google Scholar

34. Bula CJ, Wietlisbach V, Burnand B, et al: Depressive symptoms as a predictor of 6-month outcomes and services utilization in elderly medical inpatients. Archives of Internal Medicine 161:2609–2615, 2001Google Scholar

35. Webber AP, Martin JL, Harker JO, et al: Depression in older patients admitted for postacute nursing home rehabilitation. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 53:1017–1022, 2005Google Scholar

36. Borson S, Loebel P, Kitchell M, et al: Psychiatric assessments of nursing home residents under OBRA-87: should PASARR be reformed? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 45:1173–1181, 1997Google Scholar

37. The Impact of PASARR. Washington, DC, Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, 1996Google Scholar

38. Snowden M, Roy-Byrne P: Mental illness and nursing home reform: OBRA-87 ten years later. Psychiatric Services 49:229–233, 1998Google Scholar

39. Shea D, Russo PA, Smyer MA: Use of mental health services by persons with a mental illness in nursing facilities: initial impacts of OBRA87. Journal of Ageing and Health 12:560–578, 2000Google Scholar

40. Castle NG: Deficiency citations for mental health care in nursing homes. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 29:157–171, 2001Google Scholar

41. Castle NG, Myers S: Mental health care deficiency citations in nursing homes and caregiver staffing. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 33:215–225, 2006Google Scholar

42. Mor V, Angelilli J, Jones RN, et al: Inter-rater reliability of nursing home quality indicators in the US. BMC Health Services Research 3:20, 2003Google Scholar

43. Bagchi A, Verdier J, Simon SE: How many nursing home residents live with a mental illness? Presented at Academy Health Annual Research Meeting, Washington, DC, June 8–10, 2008Google Scholar