Predictors of Likelihood and Intensity of Past-Year Mental Health Service Use in an Active Canadian Military Sample

Understanding access-related issues in mental health treatment among military personnel has become increasingly important. Indeed, the mental health toll of military service in recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan ( 1 , 2 , 3 ) has highlighted the salience of access-related issues such as barriers to and disparities in treatment access. Unfortunately, only a handful of studies have examined correlates of mental health service use in military samples. With the exception of two studies ( 4 , 5 ), previous research has examined correlates of mental health service use among veterans, as opposed to active military samples.

The paucity of research on correlates of mental health service use in active military samples has meant that the role of military service variables (for example, number of deployments, duration of service, force type [that is, regular versus reserve forces], and rank) in predicting mental health service use is not well understood. A recent study of soldiers returning from the Iraq war suggests, however, that military variables such as force type can indeed have an impact on various aspects of mental health service use ( 5 ). In addition, previous studies of military samples have almost exclusively examined use versus nonuse (that is, likelihood of service use). Almost no attention has been devoted to examining associations of military variables with intensity of service use (for example, number of treatment visits). Distinguishing between mental health service use likelihood and intensity is extremely important, because it is possible that variables related to treatment use likelihood may be different from those related to treatment use intensity ( 6 ).

The study presented here attempted to address these gaps in research by looking at both a categorical aspect (use versus nonuse) and a dimensional aspect (the number of visits) of mental health care use in a large, nationally representative active military sample, using a comprehensive set of predictor variables, including those that relate specifically to the military context.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Data were drawn from the Canadian Community Health Survey-Canadian Forces Supplement (CCHS-CF), a cross-sectional population-based survey of the Canadian Forces, conducted by Statistics Canada in 2002. The target population for CCHS-CF was defined in May 2001 and included all full-time regular members (N=57,000) and reservists (N=24,000). Each target population (that is, regular force members and reservists) was stratified by gender and rank. Rank was collapsed into three categories (private, sergeant, and officer) for men and two categories (private and officer) for women. Within each design stratum, the units were sorted by geographic region (Atlantic, Central, Western, and Quebec) and Canadian Forces environment (land, air, and sea), and the final sample was obtained by using a systematic sampling scheme. After removing out-of-scope units, 6,487 regular members and 3,957 reservists were selected for interview. The interviews were conducted face to face between May 2002 and December 2002. A response was obtained for 5,155 regular members and 3,286 reservists, yielding an overall response rate of 79.5% for regular members and 83.0% for reservists and resulting in a nationally representative sample of 8,441 ( Table 1 ). A more detailed description of the study design and the sampling frame can be found in earlier publications that used this data set ( 4 , 7 , 8 ).

|

Measures

Sociodemographic and military characteristics. In the nondiagnostic section of the interview, participants were asked about their age, gender, racial and ethnic background, educational background, current employment, marital status, military force type, rank, environment, geographic region, service duration, and number of deployments.

Diagnostic assessment. The diagnostic section was based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) ( 9 ), a structured interview (administered in person by lay interviewers) that generates DSM-IV diagnoses ( 10 ) and includes a screening for the following mental disorders: alcohol dependence, major depressive disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Past-year diagnoses were used for all analyses.

Mental health service utilization. The CCHS-CF inquired about past-year contact with a variety of health care providers for "emotions, mental health, or use of alcohol or drugs" (yes or no response options). The providers fell into the following eight categories: psychiatrist; family doctor, general practitioner, or medical officer; other medical doctor, such as a cardiologist, gynecologist, or urologist; psychologist; nurse, nurse practitioner, physician's assistant, or medic; social worker, counselor, or psychotherapist; religious or spiritual advisor, such as a priest, chaplain, or rabbi; and other type of professional. For each professional, the number of visits in the past year was assessed (range 1–365). The methodology for assessing mental health service utilization was very similar to that of previous epidemiological surveys such as the National Comorbidity Survey ( 11 ). On the basis of past research ( 6 ), we summed visit counts for two overarching provider categories: mental health providers (psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, counselors, and psychotherapists) and medical providers (family doctors, general practitioners, medical officers, other medical doctors, nurses, nurse practitioners, physician's assistants, and medics). We excluded religious or spiritual advisor and other type of professional categories because they did not fit into the two provider categories and were endorsed by only a small number of respondents, leading to problems with using maximum likelihood estimation methods for these two provider types.

Statistical analyses

To produce estimates from the survey data that are representative of the Canadian Forces population, a final survey weight was created and applied to each respondent and used in all statistical analyses. This weight reflects adjustments for initial sampling, sample reduction, removal of out-of-scope units, and nonresponse. Details regarding the final survey weight can be found in prior publications using this data set ( 4 , 7 ). Sample distributions (Ns) throughout the manuscript reflect the weighted number of respondents and are rounded to the nearest whole number.

Prediction of past-year mental health service use

Theoretical framework. In predicting service use likelihood and intensity, we used a well-established theoretical model, Andersen's behavioral model of health service use ( 12 ), which explains why people use health services. According to the behavioral model ( 13 ), three factors explain health care use: predisposing characteristics, involving sociodemographic variables, such as gender; enabling characteristics, involving factors related to one's ability or access to treatment resources, such as employment status; and need variables, encompassing one's perceived or objectively assessed health impairment, such as a mental health diagnosis.

Predictor variables. Predisposing predictor variables included the sociodemographic variables of age, gender, racial or ethnic background, educational background, and marital status, as well as the military variables of military force type, rank, environment, military geographic region, service duration, and number of deployments. One enabling predictor variable was used—current employment status. Need predictor variables included the presence or absence of past-year psychiatric disorders, including major depressive disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and alcohol dependence.

Outcome variables. Outcome variables were the number of unique mental health visits in the past year across the two provider categories: mental health providers and medical providers.

Univariate and multivariate analyses. Because the distributions of the two outcome variables were substantially skewed and kurtotic (for number of visits with mental health providers, the skewness and kurtosis were 7.23 and 73.24; for medical providers, 10.48 and 160.50), and because log transformations did not sufficiently normalize the distributions, linear analytic techniques were not optimal for our data. We therefore used zero-inflated negative binomial regression (ZINB), a regression analysis for count data ( 14 , 15 , 16 ) to examine univariate and multivariate associations between the predictor and outcome variables. In multivariate analyses, we controlled for predisposing and enabling variables in step 1, and we assessed the incremental contribution of the need variables in step 2 within Andersen's behavioral model of health care use ( 13 ), using the Cragg-Uhler-(Nagelkerke) R 2 statistic. Analyses were two-tailed and were performed with Stata, version 9 ( 17 ). For multivariate analyses we did not use any data imputation methods to replace missing data.

Results

Descriptive analyses of past-year service use

Past-year service use was summarized here first for the whole sample (N=8,441); it was then summarized separately for those who met (N=1,220) or did not meet (N=7,221) criteria for at least one mental disorder in the past year. Of the whole sample, only 943 (11.2%) saw either a mental health professional or a medical professional in the past year. More military members consulted a mental health provider (N=767, 9.1%) than a medical provider (N=539, 6.4%). Of the whole sample, 395 (4.7%) had one to five visits, whereas 372 (4.4%) had six or more visits with a mental health provider. Of the whole sample, 361 (4.3%) had one to five visits, whereas 178 (2.1%) had six or more visits with a medical provider.

Of those who met criteria for at least one mental disorder in the past year, 472 (38.7%) saw either a mental health provider or a medical provider. More military members consulted a mental health provider (N=396, 32.5%) than a medical provider (N=324, 26.6%).

Of those who did not meet criteria for any disorder in the past year, 471 (6.5%) saw either a mental health provider or a medical provider. More military members consulted a mental health provider (N=371, 5.1%) than a medical provider (N=215, 3.0%).

Prediction of past-year service use

Univariate analyses: mental health providers. In univariate analyses to predict past-year service use versus nonuse (that is, service use likelihood) with mental health providers, the predisposing variables of older age and longer military service duration and the need variables of past-year major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder were associated with an increased likelihood of service use. In univariate analyses to predict service use visit counts (that is, service use intensity) with mental health providers, the predisposing variables of older age, longer military service duration, and lower military rank were associated with fewer visits, whereas the predisposing variable of being in the land troops and the need variables of past-year major depressive disorder, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and social phobia were associated with more visits ( Tables 2 and 3 ).

|

|

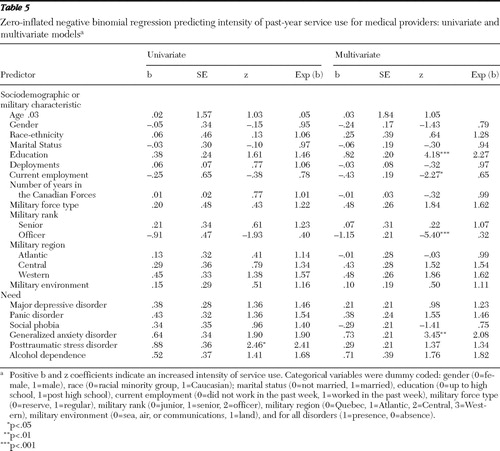

Univariate analyses: general medical providers. When using univariate analyses to predict service use likelihood with medical providers, we found that the predisposing variables of greater number of military deployments and longer military service duration and the need variables of past-year major depressive disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder were associated with increased likelihood of service use. In univariate analyses for medical providers, only the need variable of past-year posttraumatic stress disorder was associated with more visits ( Tables 4 and 5 ).

|

|

Multivariate analyses: mental health providers. In multivariate analyses to predict past-year service use with mental health providers, the predisposing and enabling factors in step 1's overall ZINB regression model were significant ([N=8,092] likelihood ratio [LR] χ2 =267.16, df=31, p<.001), contributing 4.6% variance. Variables significantly associated with greater service use likelihood included being in the regular forces and lower military rank. Variables significantly associated with greater service use intensity included being unemployed, being in the regular forces and the land troops, and having a lower rank. Step 2 added a significant amount of variance (14.2%) ([N=8,092] LR χ2diff =879.75, df=12, p<.001). Thus, the final model accounted for 18.9% of the variance in service use with mental health providers ([N=8,092] LR χ2 =1,146.91, df=43, p<.001). In the final model, older age, being in the regular forces, female gender, lower rank, past-year major depressive disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder were all associated with greater likelihood of service use. Being in the regular forces, nonmarried status, fewer deployments, unemployment, lower rank, and past-year panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder were all associated with more visits ( Tables 2 and 3 ).

Multivariate analyses: general medical providers. In multivariate analyses to predict past-year service use with medical providers, step 1's overall ZINB regression model was significant ([N=8,092] LR χ2 =211.85, df=31, p<.001), contributing 4.7% variance. Significant predictors of greater service use likelihood included the predisposing variables of being in the regular forces and unemployment. Variables significantly associated with greater service use intensity included higher education and lower rank. Step 2 added a significant amount of variance (16.7%) ([N=8,092] LR χ2diff =803.85, df=12, p<.001). Thus the final model accounted for 21.4% of the variance in likelihood of service use with medical providers [N=8,092]LR χ2 =1,015.69, df=43, p<.001). In the final model, female gender, lower rank, past-year major depressive disorder, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder were associated with greater likelihood of service use. Higher education, lower rank, unemployment, and past-year generalized anxiety disorder were associated with more visits ( Tables 4 and 5 ).

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to identify patterns and predictors of past-year mental health service use likelihood and intensity in an active military sample.

Patterns and predictors of service use likelihood versus intensity

In this study, we found that only a small portion of the whole sample accessed available mental health services in the past year. Specifically, 9.1% of the whole sample saw a mental health provider and 6.4 % saw a general medical provider in the past year. A recent study that used data from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R) study found past-year contact with mental health providers and medical providers to be 9.5% and 11.2%, respectively, in the U.S. civilian population ( 6 ). Thus our results indicate that contact with mental health providers in the Canadian military may be similar to what has been reported in the U.S. civilian population but that contact with medical providers (for mental health problems) is lower in the Canadian military than in the U.S. civilian population.

In this study, among military members with a mental disorder, less than four out of ten accessed available mental health services in the past year. This finding parallels findings from a recent study in the U.S. military that showed that only 23% to 40% of military members who served in Iraq or Afghanistan and met criteria for a disorder sought care for their condition ( 3 ).

A significant portion of contacts for both mental health and general medical providers in this sample were initiated by those without a mental disorder in the past year. This finding parallels those from civilian studies both in the United States ( 18 ) and Canada ( 19 ). Such a finding, as discussed elsewhere ( 20 ), suggests that meeting diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder is not a perfect measure of need for services for a variety of reasons, including imprecision of diagnosis and lack of specific need measures. This also suggests that unmet need (that is, the proportion of the sample that needs services but has not accessed them) is likely to be underestimated in this study.

In our univariate and multivariate analyses we found that across general medical and mental health providers, psychiatric need variables—especially anxiety disorders—were consistently related to both service use likelihood and intensity, whereas predisposing and enabling variables were not consistent in predicting of mental health service use likelihood and intensity. These findings replicate results from earlier studies in this Canadian military population that found that psychiatric need factors were the most consistent predictors of lifetime and past-year service use likelihood. Our findings extend this literature by showing that psychiatric need factors—especially anxiety disorders—are the most consistent predictors of service use intensity as well ( 4 , 7 ). The relative importance of psychiatric need variables in predicting service use has important clinical and administrative implications in the military health care context, especially for general medical providers who typically function as gatekeepers to mental health services: medical providers should carefully assess the presence of mood and anxiety disorders to determine the mental health service needs of active military members. Such "routine" assessment of psychiatric need can both minimize delays in getting to treatment and ensure the appropriate allocation of resources to various mental health services.

Relative contribution of variables in predicting service use

In multivariate analyses, we estimated the incremental contribution of mental health variables to the prediction of past-year service use, after controlling for predisposing and enabling variables. For past-year service use with mental health providers, only a small amount of variation (5%) was explained by predisposing and enabling variables. In contrast, psychiatric need variables explained approximately three times more variation (14%) above and beyond that accounted for by predisposing and enabling variables. The findings were strikingly similar when past-year service use with medical providers was explored: predisposing and enabling variables explained only 5% of the variation, whereas psychiatric need variables explained 17%. In sum, regardless of provider category type, we found that psychiatric need variables added incrementally to the prediction of past-year service use in this active military population and explained about three times as much variation in our outcomes as all other variables did. These findings again underscore the relative importance of psychiatric need variables in predicting mental health service use in various populations ( 13 ).

Military variables

In this study, in univariate analyses we found that longer military service duration was associated with increased likelihood of service use across the two provider types. This finding may in part be explained by the fact that in military populations, individuals may delay seeking treatment for fear that it may prematurely end their military career ( 3 , 21 , 22 , 23 ), especially before completing the number of years of military service required for pension or retirement eligibility. Given that pension and retirement eligibility and benefit amounts depend, in part, on the number of years the individual has served in the military, it makes sense that those with longer military service duration—having met pension eligibility requirements—would be more likely to use services. It is also possible, however, that longer service duration may be associated with greater likelihood of developing a mental disorder (and using mental health services as result). In additional analyses to test this hypothesis (available on request), support was found for the idea that longer military service duration is associated with increased likelihood of having a mental disorder. It is also noteworthy that in multivariate analyses that controlled for the effects of mental disorders, the association between military service duration and likelihood of mental health service use became nonsignificant. Together, these observations suggest that in this study, mental disorders may very well account for the relationship between military service duration and mental health service use.

In multivariate analyses, military rank also emerged as a significant predictor of service use likelihood and intensity, even after the analyses controlled for the effects of mental disorders and sociodemographic factors. The association between higher military rank and decreased service use likelihood and intensity may be due to the fact that military members with higher rank hold more publicly scrutinized positions within the military and as a result may feel both a greater fear of stigma and a greater sense of obligation to overcome their mental health symptoms on their own ( 3 ). Unfortunately, we did not possess sufficient data on stigma or other service barrier variables to test this hypothesis.

Strengths and limitations

Our study had a number of strengths. First, our study, with its active military sample, is a significant addition to the literature on mental health service use, which until now has been mostly limited to civilian and veteran populations. Second, our study used data from a large, epidemiological survey that yielded a nationally representative sample of an active military population. Existing studies on mental health service use in military populations have been conducted in small samples representing various service eras or larger samples of personnel who have served in specific deployments (primarily Vietnam), which have limited their generalizability. Finally, our study went beyond simple rates of service use and attempted to predict both service use likelihood and intensity in a military population.

Our study also had a number of limitations that should be considered in interpreting the results. First, the cross-sectional nature of our study precludes drawing any conclusions on causality. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine the direction of the associations observed. Second, respondents were asked to recall past-year service utilization behaviors. Recall bias could have led those who use services to exaggerate and those who did not use services to underreport their psychiatric symptoms. As has been suggested elsewhere ( 24 ), recall bias can lead to underestimation of the prevalence of a disorder and overestimation of service utilization. In addition, when queried about past-year service use, individuals have a tendency to forget the number of visits and estimate downward, leading to a possible underestimation of service use intensity ( 25 , 26 ). Military members may also be reluctant to report mental health problems and contact with mental health professionals for fear this may have an adverse impact on their military career. In our regression analyses we used presence of a disorder as the sole indictor of need for treatment. However, as shown by our descriptive analyses, many military members in our sample who did not meet criteria for a disorder still felt a need for treatment and accessed services. This suggests that there are other indicators of need for treatment which should be included in future studies that attempt to predict mental health service use in military populations. Finally, the sample for our study was drawn from the Canadian military, which may have a different health care system than that of other military or civilian samples.

Conclusions

Within the limitations outlined, our study shows that many active military members did not use available mental health services. This finding underscores the importance of continued efforts to destigmatize mental health treatments in the military context. In this study, psychiatric need variables consistently predicted mental health service use, and predisposing military variables also contributed to the prediction of mental health service use, albeit in a less consistent manner. This finding highlights the relative importance of psychiatric need factors in predicting service use and suggests that military variables deserve closer examination as potential predictors in future studies.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Dr. Fikretoglu acknowledges a postdoctoral fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) while working on the manuscript. The authors of this article acknowledge that they gained access to the CCHS-CF data set after it became publicly available, but they were not involved in the design of the study or the collection of the data. The study was designed under the leadership of the Department of Defense, Canada, and the data were collected by Statistics Canada. The secondary analyses presented in this article were supported by a small, internal grant from Veterans Affairs Canada.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Hoge C, Terhakopian A, Castro C, et al: Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with somatic symptoms, health care visits, and absenteeism among Iraq war veterans. American Journal of Psychiatry 164:150–153, 2007Google Scholar

2. Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS: Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA 295:1023–1032, 2006Google Scholar

3. Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, et al: Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine 351:13–22, 2004Google Scholar

4. Fikretoglu D, Brunet A, Guay S, et al: Mental health treatment seeking by military members with PTSD: findings on rates, characteristics, and predictors from a nationally representative Canadian military sample. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 52:103–110, 2007Google Scholar

5. Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW: Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. JAMA 298:2141–2148, 2007Google Scholar

6. Elhai J, Ford J: Correlates of mental health service use intensity in the National Comorbidity Survey and National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychiatric Services 58:1108–1115, 2007Google Scholar

7. Fikretoglu D, Brunet A, Schmitz N, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder and treatment seeking in a nationally representative, military sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress 19:847–858, 2006Google Scholar

8. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al: Combat and peacekeeping operations in relation to prevalence of mental disorders and perceived need for mental health care. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:843, 2007Google Scholar

9. Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): Version 2.1. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1997Google Scholar

10. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

11. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:593–602, 2005Google Scholar

12. Andersen RM, Newman JF: Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Memorial Quarterly—Health and Society 51:95–124, 1973Google Scholar

13. Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1–10, 1995Google Scholar

14. Elhai J, Ford J: Statistical procedures for analyzing mental health services and costs data. Psychiatry Research 160:129–136, 2008Google Scholar

15. Hall D, Zhengang Z: Marginal models for zero inflated clustered data. Statistical Modeling 4:161–180, 2004Google Scholar

16. Long J: Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables. Thousand Oaks, California, Sage, 1997Google Scholar

17. Stata. College Station, Texas, StataCorp, 2005Google Scholar

18. Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D: Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety or substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:77–84, 2002Google Scholar

19. Sareen J, Stein MB, Campbell DW, et al: The relationship between perceived need for mental health treatment, DSM diagnosis and quality of life: a Canadian population-based survey. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 50:87–94, 2005Google Scholar

20. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al: Perceived need for mental health treatment in a nationally representative Canadian sample. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 50:643–651, 2005Google Scholar

21. French C, Rona RJ, Jones M, et al: Screening for physical and psychological illness in the British Armed Forces: II. barriers to screening—learning from the opinions of service personnel. Journal of Medical Screening 11:153–157, 2004Google Scholar

22. Rona RJ, Hyams KC, Wessely S: Screening for psychological illness in military personnel. JAMA 293:1257–1260, 2005Google Scholar

23. Rona RJ, Jones M, French C, et al: Screening for physical and psychological illness in the British Armed Forces: I. the acceptability of the programme. Journal of Medical Screening 11:148–153, 2004Google Scholar

24. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629–640, 2005Google Scholar

25. Roberts RO, Bergstralh EJ, Schmidt L, et al: Comparison of self-reported and medical record health care utilization measures. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 49:989–995, 1996Google Scholar

26. Wallihan DB, Stump TE, Callahan CM: Accuracy of self-reported health services use and patterns of care among urban older adults. Medical Care 37:662–670, 1999Google Scholar