Association Between Staff Factors and Levels of Conflict and Containment on Acute Psychiatric Wards in England

For some time our research group has been conducting a research program that aims to elucidate staff factors contributing to conflict and containment rates on wards. By conflict we mean violence, verbal abuse, rule breaking, use of alcohol or illegal drugs, self-harm, medication refusal, and absconding by patients. Containment refers to methods used by professionals to manage or prevent such behaviors—for example, seclusion, special observation, detention during hospitalization, searching procedures, restrictions on inpatients, intensive care, manual restraint, and enforced medication. The inclusion of self-harm means that treatment refusal and disruption can also be included under the umbrella of "conflict." A conceptual analysis ( 1 ) has shown that the fundamental ideas underlying these events are the threat to safety (patients, staff, or others) and the use of safety practices by the staff.

This grouping is more coherent than other conceptual frameworks, such as "challenging behavior," because it makes the critical criterion the potential consequences of the behaviors concerned—not the patients' motivations or some scheme of moral judgment. It is supported by good levels of internal consistency across differing types of conflict, both for patients as well as for wards and shifts. That analysis also showed that although some containment was reactive to patient conflict behaviors, other containment events were preventive or therapeutic in nature. Furthermore, the analysis showed that some proportion of all conflict events were reactive to the containment endeavors of the staff, meaning that there is a reciprocal relationship between conflict and containment on wards.

The aim of our research program was to determine the most effective means to reduce both conflict and containment, while preserving the optimum level of safety. Early studies on absconding ( 2 ), ward rules ( 3 ), and nurses' attitudes toward patients with personality disorder ( 4 ) have led to the development of research instruments and a working model of the staff factors influencing conflict and containment rates. The instruments used in the research program were the Attitude to Personality Disorder Questionnaire (APDQ) ( 5 ), which sought to capture a representation of the feelings evoked by patients who behave in a difficult and challenging manner, and the Patient-Staff Conflict Checklist (PCC-SR) ( 6 ), a tool to assess the frequency of carefully defined conflict events. The interim theory, or working model that was derived from our previous empirical research, suggested that three staff factors are important in the determination of conflict rates on wards: positive appreciation of patients, self-regulation of emotional responses to patient behavior (particularly anger and fear), and provision of an effective structure of rules and routines for patients. These three factors were specified to rely upon psychiatric philosophy (high importance given to psychosocial factors in the cause and treatment of illness, psychological understanding of behavior, and individualized formulations of problems), moral commitments (honesty, equality, and courage), technical mastery (social skills and extent of behavioral repertoire), teamwork skill (consistency, cohesion, and mutual support), and organizational support (policy clarity about rules for patient conduct, training provision, and clinical supervision structures). A full description of the working model has been published previously ( 4 ). A longitudinal study to test some of the central hypotheses has also recently been completed ( 7 ).

The City-128 study, conducted from 2000 to 2005, provided an opportunity to test these theoretical ideas. This cross-sectional multivariate study of a large number of acute psychiatric wards, with their personnel and patients, utilized the instruments described above and had the primary aim of assessing the relationship between the use of special observation and self-harm. It was informed by the working model, and the staff attitude and group functioning measures were selected for their fit with it. Specific results in relation to observation and self-harm have been published elsewhere ( 8 ). The large data set collected during the study also allows a number of interesting secondary analyses, including the one presented here.

This study tested the hypothesis that staff factors have a significant influence on conflict and containment rates on wards. Specifically, better attitudes toward patients who behave in a difficult and challenging manner, team functioning, leadership, and ward structure were hypothesized to be associated with lower rates of conflict and containment.

Methods

Sample

A multivariate cross-sectional study was conducted. The sample comprised 136 acute psychiatric wards with their patients and staff in 67 hospitals within 26 National Health Service (NHS) Trusts (organizational units with common clinical policies and investment levels) in England in 2004–2005. These hospitals were proximate to three regional centers. Acute psychiatric wards were defined as those that primarily serve adults with acute mental disorders, that mostly take admissions directly from the community, and that do not offer long-term care or accommodation. Wards organized on a specialty basis were excluded, as were wards that planned to change the population served, location, or function or that were scheduled for refurbishment during the course of the study. Each center identified all eligible wards within reasonable traveling distance of its research base. The initial intent was to randomly sample wards, with replacement for refusals to participate. However, the geographical dispersion of wards outside of London meant that to achieve the requisite sample size, two centers had to recruit all available wards within practical reach for data collection. In London, it was possible to randomly sample from a list of 112 wards. The 136 acute psychiatric wards that participated in the study represented 25% of the estimated total of 551 wards in England. The study was approved by the North-West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee.

Instruments and response rates

The PCC-SR, an end-of-shift report by nurses on the frequency of conflict and containment events ( 9 ), was used to collect data for a six-month period on all participating wards. At the end of each shift, all nurses on a ward were asked to complete the PCC-SR. Upon entry to the study, ward nursing staff received training in the use of the PCC-SR, and each ward was provided with a handbook giving definitions of items. In recent tests based on use with case note material, the PCC has demonstrated an interrater reliability of .69 ( 9 ) and has shown a significant association with rates of officially reported incidents ( 10 ). This form was also used to collect a limited amount of data on patients (age, gender, ethnicity, diagnosis, reason for admission, and postal code). Postal codes were matched with local area social deprivation data (for example, income, employment, crime, and educational attainment) to yield deprivation scores for each hospital ward (Index of Multiple Deprivation) ( 11 ). Information on the physical environment of the ward (including scoring of hygiene, décor, time since last redecoration, and number of repairs pending) was summed into a physical environment quality score; the policies in operation were collected on a site visit by a researcher and a form completed by the ward manager.

Additional instruments used included the Attitudes to Containment Measures Questionnaire (ACMQ), which had been used in three countries to measure the relative acceptability of different containment methods and had been found to be related to traditional usage patterns of containment ( 12 , 13 ); the APDQ, which measures staff's attitude toward persons with a personality disorder and has been found to be related to job performance, stress, and burnout and to be sensitive to change over time and to have good test-retest reliability ( 5 , 14 , 15 ); the Ward Atmosphere Scale (WAS), which has been utilized in many studies and has been found to be related to outcomes and to display good reliability ( 16 , 17 ); the Team Climate Inventory (TCI), which has been validated with 121 teams from oil companies, psychiatric services, primary health care, and social services ( 18 ); the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ), which is underpinned by the theory of transactional and transformational leadership and has demonstrated good reliability and validity ( 19 ); and the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), which has been utilized in many studies and has been found to be related to a range of outcomes, including intention to quit ( 20 ). For nearly all these instruments, higher scores represent more of the quality measured—that is, greater approval of containment or more positive attitudes toward patients with a personality disorder. Only in the case of the MBI do two scores represent greater negative qualities: emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. The scales have been widely used and have well-established validity and reliability. These were distributed to participants by the researchers and were returned anonymously via a research "post box" provided to each ward.

Response rates for the study were good overall, averaging 51% across all questionnaires, although these response rates did vary by ward. More than 50,000 questionnaires and PCC-SRs were collected during the study ( Table 1 ). In addition, information was collected on 11,128 admissions, of which 4,112 had valid postal codes that could be matched to local area geographical data. The possibility of PCC-SR response bias was assessed by examining the relationship between total conflict and containment frequency by ward and the number of PCC-SRs submitted. An inverse correlation was found between response rate and mean total conflict events per day (r=-.27, p=.002), and there was a trend toward a similar relationship with mean containment events per day (r=-.15, p=.08). PCC-SR response rates were also highly associated with good teamwork (all TCI subscales—for example, the participative safety subscale, r=.24, p=.004) and good ward leadership (all MLQ subscales—for example, the transformational leadership subscale, r=.34, p<.001). In combination, this suggests that wards that lacked effective structure and order had high rates of conflict and had more difficulty in participating in research. A small number of wards had a very low rate of questionnaire response (not always the same wards for the different questionnaires); however, three or more questionnaires were returned in all cases for the ACMQ completed by patients and the WAS, 99% of cases for the APDQ, 98% of cases for the TCI and MBI, 97% of cases for the ACMQ completed by staff, and 93% of cases for the MLQ. The rate of missing data within the questionnaires was low, averaging 5%, and was dealt with through mean interpolation. A full analysis of the response rates in relation to data validity and reliability can be found elsewhere ( 8 ).

|

Data analysis

The response rate is described and descriptive statistics are provided for total conflict and total containment (simple sum of all conflict or containment events during a shift). We have previously developed and tested a weighting scheme for the different types of conflict and containment ( 1 ), but we found that scheme to be very highly correlated with scores based on simply summing items and found that use of either method makes no difference to analytic outcomes ( 10 ). The analysis was conducted at the level of wards (N=136). Conflict and containment rates are therefore mean rates across the six-month sample period, standardized to wards of 20 beds to adjust for patient numbers (that is, [rate/number of beds] × 20) and equally weighted for each of the three shifts (morning, afternoon, and overnight). Questionnaires were scored, and mean scores were calculated for each ward. Significant univariate relationships with other variables were identified and are reported. Conflict and containment were then used as the dependent variables in backward stepwise multiple regression analysis (p=.05 as the criterion for continued inclusion), with statistical allowance being made for clustering by NHS Trust ( 21 ).

This analysis was first conducted separately for each domain (patient, service environment, physical environment, patient routines, conflict, containment, staff demographic characteristics, and staff group factors). Variables found to be significant in these domain analyses were then entered into a further regression analysis, resulting in a final model across all domains. Both the domain and across-domain results may report valid findings, because some variables in the across domain may be intervening (caused by some and causal of others entered in the same analysis) ( 20 ). Raw coefficients are reported, because standardized betas are not available when a clustering procedure is applied. For event-count variables, coefficients have a straightforward interpretation—for example, if medication conflict increases by one event per day, then total containment per day will increase by .245 unit, or approximately one additional containment event every four days. Adjusted r 2 is reported as a measure of model fit. Regression diagnostics utilized include the calculation of variance inflation factors, residual plots, and Cook's distance as a measure of leverage. The final modeling was repeated after outlier deletion to test the robustness of the findings. Sensitivity analysis to missing data was also completed. These analyses were conducted with Stata, version 9.

Results

The 136 wards covered diverse areas, including inner-city and rural areas. Most provided mixed-sex accommodation (N=99, 73%), with the remainder serving only males (N=18, 13%) or only females (N=19, 14%). The mean±SD number of beds on a ward was 21±3.8, and the mean number of nursing staff per bed was .99±.22 (full-time equivalents on the staffing rota for the ward), with a majority (61%±12%) holding a specific qualification in psychiatric nursing. Most wards (N=65, or 48%) had been built in the 1980s and 1990s, 23 (17%) were built in 2000 or later, 26 (19%) were built in the 1960s and 1970s, and the rest (N=22, 16%) were built before the 1960s. Only 20 (15%) wards had their own seclusion room, although 48 (35%) had access to a seclusion room on another ward; just over half (N=73, 54%) had access to an on-site psychiatric intensive care unit (a secure ward with high staff-patient ratios for the management of high-risk patients).

The mean daily rate of total conflict was 14.4±7.2, and it was 9.8±5.8 for total containments. Conflict has six components, and their mean daily frequencies are displayed in Figure 1 . The most frequent conflict component was rule breaking (50%), followed by aggression (25%), and the least frequent was self-harm (3%). Cronbach's alpha for standardized scores for these six components was .68, indicating a substantial level of consistency and reliability. Containment has ten components. The most frequently reported component was intermittent observation (53%), followed by medication when needed (22%), and the least frequent were the use of seclusion (1%) and psychiatric intensive care (<1%). Cronbach's alpha for standardized scores for these ten components was .69, also indicating a substantial level of consistency and reliability. The linear correlation between total conflict and total containment was .25 (Pearson r), which was significant at p=.003.

The distribution of total conflict and total containment had a slight positive skew (more cases at lower frequencies, tailing off into fewer cases at high frequency levels). Both were transformed to a zero skewness and normal distribution before multivariate analysis.

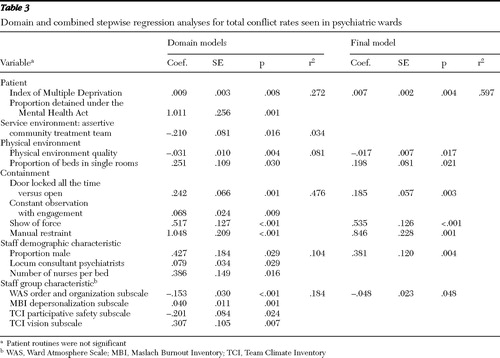

Table 2 lists the statistically significant univariate associations of total conflict and containment with other variables. As described above, models were first constructed for each domain (for example, patient characteristics and service environment). Then significant variables from these models were used to construct an overarching model. A full list of all variables included in the modeling exercise can be found elsewhere ( 8 ). Domain and full models for total conflict and containment can be found in Tables 3 and 4 .

|

|

|

A large number of patient characteristics showed univariate associations with conflict but not containment. Deprivation, social fragmentation, youth, male gender, detention under the Mental Health Act, and diagnosis of schizophrenia all showed positive associations with conflict rates. Some racial-ethnic minority categories also showed positive associations with conflict, and a greater proportion of white British admissions was inversely associated with conflict rates. However, these relationships were more complex when other factors were taken into account in a multivariate analysis. For conflict, the proportion of patients detained under the Mental Health Act and levels of deprivation remained significant, but race-ethnicity did not. For containment, the proportion of patients detained under the Mental Health Act became significant, and the characteristic of being white and British showed a positive association.

Variables tested as features of the service environment included the provision of early intervention and crisis teams, size of the ward, and availability of psychiatric intensive care. Of these, the provision of an assertive community treatment service was associated with lower rates of conflict in both the univariate and multivariate analyses, suggesting that problematic patients were being maintained outside of the hospital by this service. A similarly consistent picture was apparent for high-quality physical environment, which was associated with reduced conflict rates.

Several types of conflict showed univariate associations with total containment, but multivariate analysis confirmed that medication-related conflict was chief of these. Many types of containment were positively related to total conflict in the univariate analysis, with the most important of these being the locking of the ward door, show of force (assembly of a nursing team to promote compliance), and manual restraint.

In the univariate analysis, staff race-ethnicity appeared to be associated with total containment rates, with greater numbers of white British staff associated with higher levels of containment and greater numbers of several groups of minority staff associated with lower levels. The multivariate analysis confirmed the importance of the proportion of white staff members. In relation to total conflict, greater staff numbers and the proportion of male staff showed positive associations, as did the number of locum (temporary staff) psychiatrists.

The staff group functioning scores were closely associated with total conflict and containment in the univariate analysis: teamwork, order and organization, and feelings of security were inversely associated, whereas burnout was positively associated. These links were broadly confirmed in the multivariate analysis, with high scores on the order and organization subscale of the WAS proving to be the most robust factor associated with reduced conflict rates, and high scores on the program clarity subscale of the WAS were associated with reduced containment rates.

The highest variance inflation factor was 3.6, substantially under the level of 10 judged to represent unacceptable multicollinearity ( 22 ). Charting of the residuals indicated no other distributional problems. The use of Cook's D to identify outlying cases with high leverage located six cases for conflict and three cases for containment. Deletion of these cases for conflict led to the additional inclusion of the participative safety and vision subscales on the TCI in the final model, and deletion of these cases for containment led to the substitution of staff race-ethnicity for patient race-ethnicity in the final model.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted in order to address the potential influence of missing data on the findings. The ten lowest responding wards (returning fewer than 196 PCC-SRs) were excluded, and the analyses were repeated. For total conflict, this resulted in the exclusion of physical environment quality and proportion of beds in single rooms from the final model and the inclusion of the patient ACMQ score, security subscale of the APDQ, and acceptance subscale of the APDQ. For total containment this resulted in the exclusion of the proportion of white staff and the inclusion of the proportion of African patients.

Discussion

The main hypothesis and working model are supported by these findings, in that staff factors were significantly related to total conflict and containment rates on wards; however, the situation was more complex than the initial model suggested. That initial model indicated that many positive staff factors would contribute to lower rates of conflict and containment, such as high levels of positive feelings toward problematic patients, emotional regulation, and effective structure. Thus the model predicted that good leadership, teamwork, organization, and positive feelings about patients who behave in a difficult and challenging manner would all be inversely related to conflict and containment. This was not the case. Instead our findings showed that effective structure and order on the ward (the order and organization subscale and the program clarity subscale of the WAS) was the element of the model most strongly predictive of lower conflict and containment rates. The importance of structure relative to other staff factors is also supported by the results of a longitudinal study ( 7 ).

In addition, staff factors related to conflict and containment were different in their emphases, suggesting different (although related) causative factors. The inverse association of the program clarity subscale of the WAS and the transactional leadership subscale of the MLQ with containment might suggest that clarity of tasks and boundaries for staff may enable a sense of security that promotes less recourse to the use of containment methods with patients. Such an interpretation is further supported by the univariate inverse association of the security subscale of the APDQ with containment.

Staff group and attitude variables were intercorrelated and clearly related with each other in a complex fashion. These strong relationships may have obscured the true nature of associations with conflict and containment, particularly if some scores mediated others—for example, perhaps leadership influenced teamwork, which then influenced structure, which in turn influenced conflict and containment rates. Such underlying processes can lead to unpredictable results with multiple regression, even when multicollinearity is within acceptable levels, and this may explain the positive and negative associations of teamwork with conflict in the domain analysis. Further analytical work to disentangle the nature of these relationships will be the topic of a future publication.

In the univariate analysis, patient race-ethnicity was related to total conflict rates, with a greater proportion of patients from minority groups associated with raised rates, whereas for total containment it was staff race-ethnicity that was associated with containment rates, with a greater proportion of white staff being associated with more containment use. In the multivariate model for conflict, patient race-ethnicity was no longer significant when deprivation and formal detention rates were taken into account. However, for containment use, the relationship with staff ethnicity remained significant in the final combined model. The relationship of staff and patient race-ethnicity to conflict is complex. Our previous work with this data set has shown that patients from minority groups are more likely to be admitted for perceived risk of harm to others and formally detained, whereas white patients are more likely to be admitted informally for perceived risk of harm to self ( 23 ). Moreover, it appears that the racial-ethnic concordance of staff and patients might be more important than simple proportions in the production of conflict events on the wards (unpublished manuscript, Bowers L, Allan T, Simpson A, et al., 2008).

Patient factors were associated with conflict but not containment in the final model. This might be because patient factors have an impact on the containment rate through conflict incidents (another intervening variable problem); however, it might also suggest that containment rates are determined by local custom and practice to a greater degree. This is perhaps further supported by the differing r 2 values for the final models. Although 60% of the variance in conflict rates was explained by our model, only 32% of the variance in containment rates was similarly explained. It is known that containment usage varies greatly between hospitals and countries ( 9 , 24 , 25 ) and that even within countries certain types of containment are not available or used in some regions (for example, many wards in this study had no seclusion rooms).

The proportion of patients compulsorily admitted under mental health legislation was associated with conflict and containment. This variable may be a proxy indicator of difficult behavior, resistance to treatment, and dangerousness of the patient population on a ward. The association with containment might be through raised levels of conflict, because the relationship did not persist when conflict rates were accounted for in the final model. However, it is also possible that a significant amount of containment is about the enforcement of detention. Research on manual restraint has shown that this intervention is used more to enforce detention and treatment than to manage violence ( 26 ). This finding also suggests the possibility that conflict rates on wards might be reduced through community-based interventions, such as joint crisis plans, to reduce rates of formal detention ( 27 ). The type of conflict most strongly associated with containment rates was the refusal of medication, not aggressive behaviors or self-harm. This raises the prospect that more systematic and psychosocial ways of promoting treatment compliance might also serve to reduce containment use.

The relationship between conflict and containment was weak, with 18% of the variance in containment rates being explained by conflict, possibly because only a small proportion of containment use is an immediate response to conflict. Containment may be about the enforcement of detention and treatment and may also be preventive, being used to avert incidents that threaten staff or patient safety. However, it is also possible that containment use by staff precipitates aggression and resistance from patients. Thus, although conflict leads to containment, containment may also lead to conflict, through resistance to that conflict or through raised levels of arousal and fear among patients. Witnessing as well as undergoing containment is known to be distressing for patients ( 28 , 29 , 30 ). The model we present shows a close relationship between conflict and the harsher, more intrusive forms of containment. Not only that, but a greater proportion of the variance in conflict was explained by specific containment measures rather than vice versa (48% versus 18%) ( Tables 3 and 4 ). If a significant proportion of conflict is caused in this way, projects to reduce containment use may also serve to reduce conflict levels on the wards ( 31 , 32 , 33 ).

The main limitation of this study is the cross-sectional nature of the data set. The significant correlations reported cannot identify the direction of causality. Therefore, firm conclusions cannot be drawn from these correlations, which are subject to a variety of different interpretations. In addition, the modeling strategy used is likely to identify some variables as significant purely by chance. However, the large scale of the study, the number of potential confounding variables incorporated in the analysis, and the statistical allowance made for the clustering of responses by organization all increase the accuracy and the reliability of the findings. On a minority of wards, response rates to questionnaires were low; in isolated cases only one or two questionnaires of certain types were returned. This is likely to have affected the reliability of summary scores for these wards to an unknown extent. Further research confirming these findings is therefore desirable.

Conclusions

The findings support the theoretical validity of the concepts of total conflict and total containment as features of acute psychiatric wards, in that they show a strong reliability and give meaningful results in analysis with other variables. The findings also confirm our previous working model in that staff variables are associated with conflict and containment rates. However, only one element of the working model, the importance of effective structure, was well supported by the findings.

There are a numbers of ways in which conflict on wards might be reduced, including a greater emphasis on the production of effective structure and order on the ward, quality improvement initiatives aimed at reducing the use of harsher containment methods, improvements to the physical environment of the wards, and work in the community to reduce the numbers of compulsory admissions.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was funded by the National Institute of Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation Programme. However, the views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funding body. The funding body approved the design of the study and received regular reports on the data collection. Although other results of this study have been subject to peer review arranged by the study funding body, the analysis reported here has not. The funding body has received an advance copy of the manuscript but is not entitled to require, nor has it requested, any alterations.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Bowers L: On conflict, containment and the relationship between them. Nursing Inquiry 13:172–180, 2005Google Scholar

2. Bowers L, Jarrett M, Clark N, et al: Absconding: why patients leave. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 6: 199–205, 1999Google Scholar

3. Alexander J: Patients' feelings about ward nursing regimes and involvement in rule construction. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 13:543–553, 2006Google Scholar

4. Bowers L: Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder: Response and Role of the Psychiatric Team. London, Routledge, 2002Google Scholar

5. Bowers L, Allan T: The Attitude to Personality Disorder Questionnaire: psychometric properties and results. Journal of Personality Disorders 20:281–293, 2006Google Scholar

6. Bowers L, Simpson A, Alexander J: Patient-staff conflict: results of a survey on acute psychiatric wards. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 38:402–408, 2003Google Scholar

7. Bowers L, Hackney D, Nijman H, et al: A Longitudinal Study of Conflict and Containment on Acute Psychiatric Wards: Report to the Department of Health. London, City University, 2007Google Scholar

8. Bowers L, Whittington R, Nolan P, et al: The City 128 Study of Observation and Outcomes on Acute Psychiatric Wards: Report to the NHS SDO Programme. London, National Health Service, Service Delivery and Organisation Programme, 2007Google Scholar

9. Bowers L, Douzenis A, Galeazzi G, et al: Disruptive and dangerous behaviour by patients on acute psychiatric wards in three European centres. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 40:822–828, 2005Google Scholar

10. Bowers L, Flood C, Brennan G, et al: Preliminary outcomes of a trial to reduce conflict and containment on acute psychiatric wards: city nurses. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 13:165–172, 2006Google Scholar

11. Noble M, Wright G, Dibben C, et al: The English Indices of Deprivation 2004. West Yorkshire, United Kingdom, Office of the Deputy Prime Minister Publications, 2004Google Scholar

12. Bowers L, Simpson A, Alexander J, et al: Cultures of psychiatry and the professional socialization process: the case of containment methods for disturbed patients. Nurse Education Today 24:435–442, 2004Google Scholar

13. Bowers L, Van der Werf B, Vokkolainen A, et al: International variation in attitudes to containment measures for disturbed psychiatric inpatients. International Journal of Nursing Studies 44:357–364, 2007Google Scholar

14. Bowers L, Carr-Walker P, Paton J, et al: Changes in attitudes to personality disorder on a DSPD unit. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health 15:171–183, 2005Google Scholar

15. Bowers L, Carr-Walker P, Allan T, et al: Attitude to personality disorder among prison officers working in a dangerous and severe personality disorder unit. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 29:333–342, 2006Google Scholar

16. Moos R: Ward Atmosphere Scale Manual. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1974Google Scholar

17. Moos R: Evaluating Treatment Environments. New Brunswick, Transaction Publishers, 1997Google Scholar

18. Anderson N, West M: Team Climate Inventory (TCI): User's Guide. Windsor, United Kingdom, NFER-NELSON Publishing, 1999Google Scholar

19. Bass B, Avolio B: Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. Redwood City, Calif, Mind Garden, 1995Google Scholar

20. Maslach C, Jackson S: The Maslach Burnout Inventory. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1981Google Scholar

21. Rogers W: Regression standard errors in clustered samples. Stata Technical Bulletin 13:19–23, 1993Google Scholar

22. Neter J, Kutner M, Nactsheim C, et al: Applied Linear Statistical Models. Boston, McGraw-Hill, 1996Google Scholar

23. Bowers L, Jones J, Simpson A: The demography of nurses and patients on acute psychiatric wards in England. Journal of Clinical Nursing, in pressGoogle Scholar

24. Forquer SL, Earle KA, Way BB, et al: Predictors of the use of restraint and seclusion in public psychiatric hospitals. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 23:527–532, 1996Google Scholar

25. Sourander A, Ellila H, Valimaki M, et al: Use of holding, restraints, seclusion and time out in child and adolescent psychiatric inpatient treatment. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 11:162–167, 2002Google Scholar

26. Ryan C, Bowers L: An analysis of nurses' post-incident manual restraint reports. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 13:527–532, 2006Google Scholar

27. Henderson C, Flood C, Leese M, et al: Effect of joint crisis plans on use of compulsory treatment in psychiatry: single blind randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal 329:136, 2004Google Scholar

28. Bonner G, Lowe T, Rawcliffe D, et al: Trauma for all: a pilot study of the subjective experience of physical restraint for mental health inpatients and staff in the UK. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 9:465–473, 2002Google Scholar

29. Frueh B, Knapp RG, Cusck KJ, et al: Patients' reports of traumatic or harmful experiences within the psychiatric setting. Psychiatric Services 56:1123–1133, 2005Google Scholar

30. Robbins CS, Sauvateot JA, Cusack KJ, et al: Consumers' perceptions of negative experience and "sanctuary harm" in psychiatric settings. Psychiatric Services 56:1134–1138, 2005Google Scholar

31. Curie CG: SAMHSA's commitment to eliminating the use of seclusion and restraint. Psychiatric Services 56:1139–1140, 2005Google Scholar

32. Donat D: Encouraging alternatives to seclusion, restraint, and reliance on PRN drugs in a public psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric Services 56:1105–1108, 2005Google Scholar

33. Learning From Each Other: Success Stories and Ideas for Reducing Restraint/Seclusion in Behavioral Health. Arlington, Va, American Psychiatric Association, 2003Google Scholar