The Status of States' Policies to Support Evidence-Based Practices in Children's Mental Health

Since 1982, when Knitzer ( 1 ) documented the failure of the public systems to provide service access and high-quality care for children and youths with psychiatric conditions and their families, states have struggled to implement responsive public policies. More than 25 years later, national data show that many children and youths with mental health conditions do not receive needed services ( 2 ). Those who receive services often receive suboptimal care ( 3 ).

State policy makers see the adoption of evidence-based practices as a major strategy to improve service quality for children and youths with psychiatric conditions. In children's mental health services research, the term evidence-based practices refers to practices for which there is rigorous research that demonstrates repeated effectiveness ( 4 ). States have tried to translate proven methods into practice for children and youths through implementation of evidence-based practices ( 5 ). Although states are in a position to lead implementation efforts for evidence-based practices, they face many challenges, especially in large systems ( 6 ). These challenges center on workforce development, organizational capacity, and practice fidelity and consistency ( 7 ). However, nationally we know little about how states promote evidence-based practices. The purpose of this study was to describe states' strategies to promote the implementation of empirically supported practices in service delivery for children and youths in a national sample of state children's mental health directors.

Methods

This study draws on data from Unclaimed Children Revisited: Survey of State Children's Mental Health Directors, a national survey conducted in fall 2006 ( 8 ). This study is part of a multipronged initiative to generate new knowledge about policies across the United States that promote or inhibit the delivery of high-quality mental health services and supports to children, youths, and families in need. It includes a national survey of state children's mental health directors and advocates and a case study of mental health delivery systems for children and youths in California and Michigan.

The Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board provided a waiver of documentation of written consent for the surveys and telephone interviews. All respondents received an information sheet about the study. The state directors' survey was administered electronically by mail and the telephone.

Surveys were sent to 50 states, the District of Columbia, and four U.S. territories. Fifty states, two territories, and the District of Columbia responded (N=53), which resulted in a 96% response rate. (In this brief report we use the term "states" to refer to states, territories, and the District of Columbia.) Forty-seven respondents (89%) were state children's mental health directors or persons with similar levels of authority (titles varied depending on the state's structure of the children's mental health administration), and six respondents (11%) were the designees of directors; the positions of designees varied from assistant director to program coordinator. Fifteen respondents (28%) had been in their position for more than ten years, 11 (21%) for four to six years, eight (15%) for more than seven years, seven (13%) for one to three years, and six (11%) for less than one year. Six respondents (11%) did not state the length of their tenure.

The research protocol for the national survey was developed with assistance from state leaders in the child-serving systems, family members, advocates, and researchers and practitioners in children's mental health services through a series of meetings. A subcommittee of the Division of Children, Youth, and Families of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) reviewed draft questions for face validity. The finalized survey included 36 questions regarding states' policies, including questions on infrastructure and finance components related to the delivery of children's mental health services. The survey included both closed-ended and open-ended questions.

The survey was attached to a letter that NASMHPD sent to state children's mental health directors to encourage their state's participation. Invitations included information on participants' rights as human subjects, a survey, and a profile of utilization and resource data. These were sent by mail and electronically. Three general reminder notices were sent by e-mail for those who did not respond. Phone reminders followed. In the case of four states, the survey was administered by phone. For Puerto Rico, the survey was translated into Spanish, and the responses were returned in English. Data from returned surveys were compiled for individual states and returned to the states for verification. In this brief report, we focus on the survey questions related to states' strategies to implement evidence-based practices.

Results

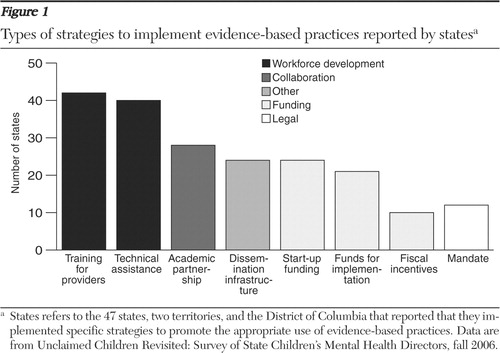

All respondents (N=53) reported on whether their state mental health authority promoted the use of evidence-based practices. Fifty states (94%) reported that their state mental health authorities are implementing specific strategies to promote the appropriate use of evidence-based practices. Three states (6%) reported that they are not engaged in any specific strategies. States' responses regarding specific strategies that they used to implement evidence-based practices fell under one of the following four categories: mandates, workforce development, funding, and collaboration. These four categories are instrumental to the dissemination of innovation ( 7 ). Strategies that fell outside of these categories were also identified through open-ended questions. States are implementing a range of strategies, from mandates (N=12) to providing fiscal incentives (N=10) or startup funding (N=24) to providing technical assistance (N=40) and training for providers (N=42) ( Figure 1 ).

As shown in Figure 1 , the most frequently identified strategies were related to workforce development and the least frequently identified were related to legal mandates. Less than half of the 50 states with strategies for promoting evidence-based practices (N=24, 48%) reported that they provide start-up funds, and only ten states (20%) reported that they make fiscal incentives available to implement evidence-based practices. Many states were unable to identify how much of their funding supports specific services, including evidence-based practices for children's mental health services, thereby making it difficult to track the impact or long-term sustainability of the services. States most frequently reported that they provide training for providers and technical assistance as a method of promoting evidence-based practices, but the nature, quality, and impact of these strategies were not described. Three of the 28 states (11%) that reported using academic partnerships as a vehicle for promoting evidence-based practices are also actively developing and supporting centers of excellence charged with the dissemination and implementation of evidence-based practices. Such centers are fully or partially funded by state children's mental health authorities. The three states that reported that they developed and support these centers were New York, California, and Ohio.

Regional differences were apparent in the type of strategies that states reported that they employ to promote, support, or require evidence-based practices. For example, states with mandates represent all regions except the Northeast. Two-thirds of states with mandates are states with populations of five million or more (N=8 of 12, 67%). Of the ten states that reported that they used fiscal incentives, four of them are from the Northeast and seven are larger states (population of five million or more).

Investigators identified three ways to gauge intentional state policy action related to implementation of evidence-based practices. These included whether there was promotion, support, or a mandate designed to further adoption of evidence-based practices. Consequently states were queried about the type of evidence-based practices that they promoted, supported, or required in open-ended questions. Most states' strategies related to evidence-based practices are not statewide. Eighteen of the 50 states with strategies for promoting evidence-based practices (36%) reported that their children's mental health authority promotes or requires the implementation of specific evidence-based practices on a statewide basis. Of the 12 states with mandates for evidence-based practices, only half (N=6, 50%) reported that they promote or require the implementation of specific evidence-based practices. Most states (N=31, 62%) promote or require implementation for limited geographic areas or pilot programs. Among the top four most frequently cited evidence-based practices that states reported they promote, support, or require are positive behavioral interventions and supports (N=18, 36%), multisystemic therapy (N=16, 32%), cognitive-behavioral therapy (N=11, 22%), and functional family therapy (N=10, 20%). Eleven states (22%) also reported using the wraparound process, a best practice in service delivery. Of the 50 states with strategies, four (8%) did not comment on the specific evidence-based practices that they promote, support, or require. [A figure showing the most frequently reported evidence-based practices is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

Research suggests that information systems facilitate the adoption and implementation of evidence-based practices and quality initiatives ( 9 ). However, few states reported that they link their approaches for evidence-based practice implementation to efforts to improve information systems and outcomes tracking. Over one-third of states (N=16, 32%) described their information technology infrastructure as rudimentary. One-fourth (N=13, 26%) reported limited capacity for making outcome-based decisions. Linking efforts to improve and monitor quality varied. Eight states (16%) mandate the use of evidence-based practices and require specific practices statewide. Only one of these states also reported having both advanced information systems and the capacity to make outcome-based decisions. Between 50% and 86% of states reported having specific information systems-related strategies designed to promote the use of mechanisms to ensure quality, ranging from efforts to promote electronic health records to cross-systems outcomes and indicators ( Figure 2 ). The most frequently reported methods include those designed to improve administrative data or outcome management systems and quality assurance within the children's mental health agency (N=43, 86%). Further, the majority of states responded that they had developed specific initiatives to improve automated data information systems for clinical decision making within the children's mental health system (N=29, 58%) and to increase access to state data and its analysis for community-based planning (N=39, 78%).

On the other hand, approximately half of states with strategies for promoting evidence-based practices (N=26, 52%) have specific infrastructural support programs to promote the use of cross-system outcome indicators or electronic records. Outcome measurement and electronic record systems also facilitate implementation of evidence-based practices ( 10 ). When we examined whether the type of information technology strategies are nested within the type of strategies to implement evidence-based practices, we found that states with a focus on workforce development were more likely than other states to develop promotion efforts linked to the use of electronic records (N=23, 55%, among 42 states with training for providers; N=21, 53%, among 40 states with technical assistance). In addition, states with academic partnerships also had a higher proportion of electronic records use (N=19, 68% of 28 states with academic partnerships designed to adopt evidence-based implementation).

Further, children's mental health directors ranked the implementation of evidence-based practices high when they were asked to name the top three critical policy challenges that they faced. Eleven of the 53 state children's mental health directors (21%) identified implementation of evidence-based practices as one of the top three state- or federal-level challenges for their states. Specifically, they pointed to workforce development, capacity, and reimbursement as challenges related to uptake of these practices. Respondents were also queried on policy reforms. Seven of the 53 responding states (13%) indicated that use of evidence-based practices is one of the top three policy reforms that they would implement from either a state or federal perspective to improve children's mental health.

Discussion and conclusions

States' efforts to improve quality of care through policy face limitations in three areas: the scope of the state-driven strategies, structural supports, and funding. First, our findings suggest that many of the state-driven strategies related to evidence-based practices in children's mental health remain limited in scope. Our data identified only a limited number of states with plans for widespread dissemination of evidence-based practices, which reduces the potential impact on the quality of mental health care. Second, critical supports for the implementation of evidence-based practices are also limited. We found that even though states strongly support implementing evidence-based practices, many states do not provide the policy and infrastructural supports to ensure broad adoption and sustainability. In particular, our data indicate the need for state strategies to link to up-to-date information systems. Studies have shown that most states do not have a workforce in place to implement evidence-based practices. In addition, available advanced information systems to support evidence-based practice implementation are inferior. Furthermore, there is insufficient fiscal support for continuous capital upgrades, and there are few statewide efforts to implement outcome-based decisions ( 11 , 12 , 13 ).

Third, financing is a major obstacle to implementing evidence-based practices. Other research suggests that current funding streams and rules compel states to develop intricate strategies to support costly evidence-based practices ( 14 ). Any continuation of prior federal movement toward audit-driven and compliance-based policies may undermine states' efforts to implement and sustain these efforts. There is a need for the creation of flexibility within current payment mechanisms to reimburse for evidence-based practices as well as a need for funding that supports the implementation, particularly related to provider training and quality assurance. Future research should explore funding mechanisms to sustain the use of evidence-based practices.

The findings of our study have other policy implications. Children's mental health as a field is well-poised to join general medical care in improving quality of care. If this new energy that focuses on implementing evidence-based practices is to be sustained and linked to quality, there needs to be both federal and state commitment that focuses on statewide implementation of evidence-based practices, invests in information technology development and outcome-based measurements, and facilitates the application of the effective practices through financial incentives.

The two major limitations of this study are that it did not query states on other efforts to promote effective care beyond evidence-based practices and it relied on the informed perspectives of state children's mental health directors. The information is not otherwise verified. However, a survey of mental health advocates indicates widespread knowledge among state mental health advocates that states are promoting evidence-based practices. Sixty percent of advocates were aware of their state's efforts to promote evidence-based practices, but few knew about their state's specific strategies ( 8 ). This study provides a current snapshot of the status of states' strategies in implementing evidence-based practices.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation through grant number 204.007 and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation through grant number 64-81785-000. The authors thank Jane Knitzer, Ed.D., and Sarah Dababnah, M.P.H., who offered helpful suggestions on earlier versions of this brief report.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Knitzer J: Unclaimed Children: The Failure of Public Responsibility to Children in Need of Mental Health Services. Washington, DC, Children's Defense Fund, 1982Google Scholar

2. Kataoka S, Zhang L, Wells K: Unmet need for mental health care among US children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1548–1555, 2002Google Scholar

3. Weisz JR, Sandler IN, Durlak JA, et al: Promoting and protecting youth mental health through evidence-based prevention and treatment. American Psychologist 60:628–648, 2005Google Scholar

4. De los Reyes A, Kazdin AE: Conceptualizing changes in behavior in intervention research: the range of possible changes model. Psychological Review 113:554–583, 2006Google Scholar

5. Walrath CM, Sheehan A, Holden EW, et al: Evidence-based treatments in the field: a brief report on provider knowledge, implementation, and practice. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 33:244–253, 2006Google Scholar

6. Bruns E, Hoagwood K: State implementation of evidence-based practice for youths. part I: responses to the state of the evidence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 47:369–373, 2008Google Scholar

7. Greenhalgh T, Robert G, MacFarlane F, et al: Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Quarterly 82:581–625, 2004Google Scholar

8. Cooper JL, Aratani Y, Knitzer J, et al: Unclaimed Children Revisited: The Status of Children's Mental Health Policy in the United States. New York, National Center for Children in Poverty, 2008Google Scholar

9. Dorr D, Bonner LM, Cohen AN, et al: Informatics systems to promote improved care for chronic illness: a literature review. Journal of the American Informatics Association 14:156–163, 2007Google Scholar

10. Hensing J, Dahlen D, Warden M, et al: Measuring the benefits of IT-enabled care transformation. Health Care Financial Management 62:74–80, 2008Google Scholar

11. Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, et al: Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Annals of Internal Medicine 144:742–752, 2006Google Scholar

12. Hunsley J: Training psychologists for evidence-based practice. Canadian Psychology 48:32–42, 2007Google Scholar

13. Power K: Strategies for Transforming Mental Health Care Through Data-Based Decision-Making in Mental Health, United States, 2004. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, 2008Google Scholar

14. Cooper JL: Towards Better Behavioral Health for Children, Youth and Their Families: Financing That Supports Knowledge in Unclaimed Children Revisited. New York, National Center for Children in Poverty, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, 2008Google Scholar