Randomized Controlled Trial of Illness Management and Recovery in Multiple-Unit Supportive Housing

The President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health report of 2003 called for a sweeping transformation of the mental health system, guided by the vision of recovery as a legitimate goal of treatment ( 1 ). As part of this transformation, the commission recommended a shift from traditional, hierarchical decision making about treatment by mental health professionals to collaborative decision making between the consumer and mental health professionals about the consumer's mental health treatment. It also emphasized the importance of improving access to evidence-based practices for the treatment of mental illness.

Coincidentally with the commission's recommendations, the illness management and recovery program was developed and standardized as a cohesive intervention incorporating empirically supported methods for teaching people how to manage their psychiatric disorders ( 2 ). The program begins with an exploration of the meaning of "recovery" with the consumer, followed by the identification of personal goals related to that individual's own concept of recovery. Goals are broken down into steps, and the clinician then teaches illness self-management skills using a combination of psychoeducational, cognitive-behavioral, and motivational teaching strategies to help the consumer make progress toward achieving those goals. Five empirically supported practices for teaching illness self-management, identified in a comprehensive review of controlled research literature ( 3 ), have been incorporated into the program, including psychoeducation about mental illness and its treatment, behavioral training to improve medication adherence by teaching strategies for incorporating the taking of medication into one's daily routine, relapse prevention planning, coping skills training to manage persistent symptoms, and social skills training to improve social support. The program can be provided in an individual or group format and usually requires nine to ten months of weekly sessions or four to five months of semiweekly sessions to complete.

Research has demonstrated that the program can be implemented with good fidelity to the model ( 4 ), and open clinical trials support the program's feasibility and suggest that it is associated with improved outcomes in illness self-management and functioning ( 5 ). In addition, one randomized controlled trial has been conducted in Israel, which provided support for the effects of the program on illness self-management outcomes ( 6 ). Thus preliminary research suggests that the program is feasible to implement in routine mental health treatment settings and has beneficial effects on illness-related outcomes. However, no controlled research on the program has been conducted and published in the United States. This article describes the results of the first controlled study of the program in the United States.

Methods

The study was a randomized controlled trial to compare the illness management and recovery program with a waitlist control. The trial was conducted at an agency that provides a broad range of services for persons with serious mental illness. Recruitment was conducted between September 2006 and January 2007. Research procedures were approved by the agency's institutional review board (IRB).

Participants

Participants were recruited from three multiple-unit supportive housing sites in New York City serving racially and ethnically diverse populations with and without serious mental illness. The support services were provided by a single nonprofit agency. Eligibility criteria for participation included serious and persistent mental illness according to New York State Office of Mental Health guidelines, defined as a DSM-IV -diagnosed mental illness with substantial, extended functional impairment ( 7 ); current residence in one of the three supportive housing sites; proficiency in English; and willingness to provide informed consent. Written informed consent was obtained from participants after complete description of the study, including assurance that housing and other support services were in no way contingent on participation. A total of 104 participants gave informed consent and completed baseline assessments before random assignment to the intervention or to the control condition. After completion of the baseline assessment, participants were randomly assigned to their study groups by drawing tokens to one of seven program classes (N=54) or to a waitlist control condition (N=50), stratified by gender.

Measures

Illness self-management and pursuit of recovery goals, quality of life, psychiatric symptoms, suicidality, and substance use were assessed at baseline, five months postbaseline, and at follow-up one year postbaseline. Participants were reimbursed $30 for each assessment. Psychiatric hospitalizations, employment status, and interest in employment were assessed at baseline and at one year of follow-up. Substance use and illness self-management (clinician scale) ratings were provided by participants' case managers or supervisors, who were familiar with the participants and who were not blind to treatment assignment. All other assessments were obtained by two trained clinical interviewers—a licensed clinical psychologist and a master's-level psychologist—both of whom were blind to treatment assignment.

Ninety-nine participants completed the five-month postintervention assessments (52 from the program and 47 in the control group), and 88 completed the one-year follow-up assessment (44 each from the program and control groups). Reasons for noncompletion at follow-up were refusal or nonresponse (six program and two control group participants), death (two program and two control group participants), incarceration (one program and one control group participant), hospitalization (one control group participant), and military service (one program participant).

Interviewers were trained by rating videotaped and live interviews before conducting baseline assessments, with the process repeated before beginning the postintervention assessments. All interviews were audiotaped, and tapes were randomly selected for cross-rating on the two measures requiring interviewer judgment (the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale [BPRS] and the Abbreviated Quality of Life Scale [QLS-A]). The integrity of interviewer blinding was tested once all assessment interviews were completed by having interviewers guess the treatment assignment of each participant. A chi square test was not significant, indicating that the interviewers were unable to distinguish treatment assignment and suggesting that the blinding procedures worked properly.

Primary outcomes

Illness self-management and the pursuit of recovery goals were measured with the Illness Management and Recovery Scales (IMRS) ( 8 ). These are 15-item behaviorally anchored scales with parallel client self-report and clinician versions. The scales are designed to capture illness self-management domains targeted by the program, including knowledge about mental illness, medication adherence, relapse prevention, social support, coping efficacy, and substance use and dependence. They have been shown to have good internal and test-retest reliability and convergent validity among people with serious mental illness ( 9 , 10 ). Scores are reported as the mean across items, excluding missing items.

Psychosocial functioning was assessed with the QLS-A ( 11 ). The QLS-A is a seven-item scale that has been demonstrated to accurately predict total scores on the original, 21-item Heinrichs Quality of Life Scale (QLS) ( 12 ), a widely used measure of quality of life and community functioning of people with serious mental illness that taps quality of relationships, role functioning, intrapsychic foundations (such as sense of purpose), and common objects and activities (such as owning an alarm clock). Scores were reported as item means, with missing items excluded. Forty-one QLS-A assessments were cross-rated from audiotape by the alternate interviewer, with an intraclass correlation coefficient of .91, indicating high interrater reliability.

Symptoms were assessed with the expanded version of the BPRS ( 13 ) and the Modified Colorado Symptom Index (MCSI) ( 14 ). The BPRS is a 24-item scale in which the interviewer rates the severity of psychiatric symptoms over the previous two-week period. It has been widely used in studies of people with serious mental illness. Statistical analyses were conducted on the total BPRS score and on four subscale scores established by Velligan and colleagues ( 15 ): activation, depression and anxiety, psychosis, and retardation. Forty-one BPRS assessments were cross-rated from audiotape by the alternate interviewer, with an intraclass correlation coefficient of .94, indicating high interrater reliability. The MCSI is a 14-item self-report scale that rates the frequency of psychiatric symptoms over the previous 30 days. The scale has been shown to be reliable and valid for individuals with serious mental illness ( 16 , 17 ). Total scores are reported; missing items were replaced by the mean of that item for all respondents.

Secondary outcomes

Several secondary outcomes were also measured. Suicidal behavior was evaluated with the Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R), a four-item self-report scale that rates past, present, and predicted suicidal ideation and behaviors. The scale has been shown to be reliable and valid for people with serious mental illness ( 18 ). Substance abuse and dependence were measured with the revised versions of the Alcohol Use Scale (AUS-R) and Drug Use Scale (DUS-R) ( 19 ). The AUS-R and DUS-R were completed by participants' case managers or supervisors on the basis of all available information about an individual's substance use over the past six months (including self-report, collateral report, and records), with a final rating on a 5-point scale corresponding to DSM-IV criteria for substance use disorders: 1, abstinence; 2, use without impairment; 3, abuse; 4, dependence; and 5, severe dependence with institutionalization. These scales have been widely used in studies of people with serious mental illness and have been shown to be reliable and valid in this population ( 20 , 21 ). Psychiatric or substance-related hospitalizations over the past year were measured in the interviews by participant self-report at baseline and 12-month follow-up. Self-reported current work status and interest in working were also collected by the interviewers at the same points.

Treatments

All study participants received supportive housing as defined by the Corporation for Supportive Housing: housing units available to individuals who are homeless or at risk of homelessness and have multiple barriers to housing and employment; rent and utility payments no greater than 30% of household income; a lease held by the tenant with no limits on length of tenancy; easy access to a range of supportive services to maintain housing stability; and proactive efforts to engage participants in psychiatric, rehabilitative, medical, and other services designed to foster personal growth and community integration ( 22 ). Specific services provided at the study sites included case management, psychiatric treatment, and primary medical care as needed to supplement community providers; referral to and coordination with community-based services; recreational and therapeutic facilities, such as weight rooms, program libraries, and music rehearsal rooms; and activities, including knitting circles, yoga classes, photography instruction, movie screenings, and field trips.

Illness management and recovery program

Program participants were engaged in sessions conducted twice weekly for approximately 20 weeks or 41 sessions. Class size ranged from five to eight participants, with sessions lasting approximately one hour, typically cofacilitated by two leaders. Classes were conducted at the supportive housing residences.

Program sessions were taught in a classroom format with participants referred to as "students." Homework assignments were chosen by participants to supplement in-class work, and significant others were encouraged to support students' self-management of their psychiatric illnesses (with participants' permission). Class sessions followed the revised program manual ( 23 ) and covered the following topics: recovery strategies, practical facts about serious mental illness, stress-vulnerability model and treatment strategies, building social support, using medications effectively, reducing drug and alcohol use, reducing relapses, coping with stress, coping with problems and persistent symptoms, and getting needs met in the mental health system.

Fidelity to the illness management and recovery model was evaluated by a consultant external to the service and research teams, with extensive experience in program implementation and evaluation. The evaluation used the 13-item fidelity scale developed for the program resource kit and drew upon a structured review of randomly selected progress notes, attendance-tracking documentation, and interviews with class leaders regarding their knowledge of the practice ( 24 ). The mean±SD item score for program fidelity was 4.38±1.19, which is considered good fidelity and above the average score of the 12 centers that implemented illness management and recovery in the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices project ( 4 ).

Rate of exposure to the program was determined by calculating the percentage of participants who attended at least half (or 21) of the 41 scheduled sessions. Twenty-nine of 54 participants (54%) assigned to the program attended at least 21 sessions (mean=33.8±6.1) and were considered exposed to the program, whereas 25 participants (46%) who attended fewer than 21 sessions (mean=7.0±6.6) were considered unexposed. Participants exposed to the program did not differ from unexposed participants on any demographic or diagnostic characteristics, although a significantly greater proportion of the latter reported a psychiatric or substance-use-related hospitalization in the year before baseline assessment ( χ2 =6.11, df=1, p=.013).

The low exposure rate spurred an IRB-approved supplemental investigation of reasons for nonattendance. Focus groups and individual interviews were conducted with participants who were exposed to program classes and with those who attended fewer than 11 classes.Three focus groups were conducted with a total of 16 exposed participants.Five unexposed participants were also interviewed. Each focus group and interview lasted approximately 60 minutes. All participants were paid for their participation and provided informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Chi square tests were used to check for baseline between-group differences on nominal demographic and diagnostic variables. Differences in ordinal and interval variables were evaluated with t tests.

Intent-to-treat analyses were conducted to compare program participants with the control group on all outcomes. Relative change in illness self-management and pursuit of personal recovery goals, quality of life, psychiatric symptoms, suicidality, and substance use were evaluated for postintervention and one-year follow-up data with univariate, repeated-measures, linear mixed models (restricted maximum likelihood method [ 25 , 26 , 27 ]) that assumed unstructured covariance, with baseline scores entered as random covariates and posttest and subsequent scores as the repeated measures. We did not assume or estimate a time trend for the measures, nor did we report on impact of the baseline covariates, which were not variables of interest. Linear mixed models were selected for their capacity to accommodate missing longitudinal data ( 28 ).

Analyses of variance showed no significant differences between program classes on change in these outcomes, and specific program class was excluded from the analyses. Effect sizes were calculated as the difference in mean group scores from baseline to last available assessment (when no posttreatment or follow-up data were available, no change was assumed), divided by pooled standard deviation. Dichotomous measures of hospitalization, work status, and interest in working were evaluated for change from baseline to follow-up with McNemar tests ( 29 ).

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS, release 14.0.2. One-tailed tests from linear mixed models were used based on the hypothesis that clients in the program would show greater improvement on all primary outcomes. All other statistical tests were two-tailed. To explore whether outcomes were affected by exposure to the program for clients assigned to it, the above analyses were repeated to compare the control group with those exposed to the program.

Results

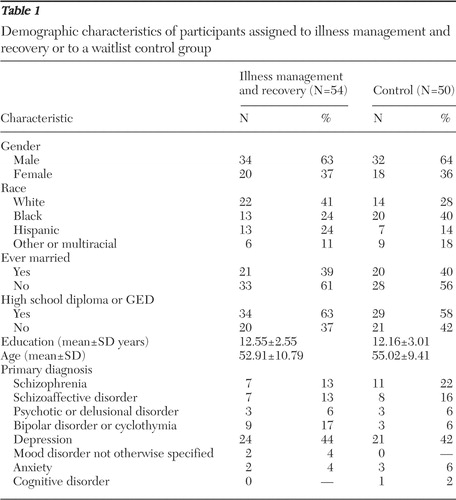

Descriptive characteristics of the study sample are summarized in Table 1 . A significantly greater proportion of Caucasian participants were randomly assigned to the program than to the control group ( χ2 =4.09, df=1, p=.043), and program participants had significantly lower baseline scores on the BPRS activation subscale than the control group (mean=2.41±2.72 and 4.32±4.54, respectively; t=–2.58, df=79, p=.012). Neither of these variables was significantly related to any of the dependent variables in the study's linear mixed models, and therefore they were not included in the final analyses. There were no other statistically significant between-group baseline differences.

|

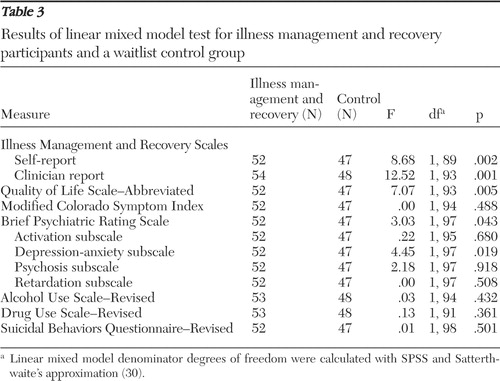

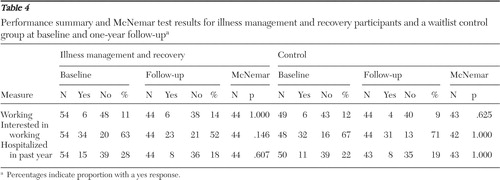

Descriptive information about the outcomes for the program and control groups, and the results of the statistical analyses comparing the groups, are summarized in Table 2 (scores and effect sizes for continuous outcomes), Table 3 (linear mixed models for continuous outcomes [ 30 ]), and Table 4 (scores and McNemar tests for dichotomous outcomes). Compared with those on the waitlist, the program participants demonstrated significantly greater gains in illness self-management as measured on both the client and clinician IMRS ( Table 3 ). Program participants also improved significantly more in psychosocial functioning on the QLS-A than did the waitlist control group. Finally, program participants experienced a significantly greater reduction in BPRS total score and on the BPRS depression-anxiety subscale compared with the control group. There were no statistically significant treatment effects on any of the other BPRS subscales, nor on the self-reported MCSI. There were no statistically significant treatment effects on any of the secondary outcomes, including suicidality and alcohol and drug problems ( Table 3 ) and employment and interest in working ( Table 4 ).

|

|

|

The analyses comparing the subgroup of clients exposed to the program with the control group were similar to the intent-to-treat analyses, with two exceptions. The group effect on the IMRS ratings of both the client (F=19.14, df=1 and 69, p<.001, effect size=.75) and clinician (F=22.55, df=1 and 70, p<.001, effect size=.59) was much stronger in the exposure analyses than in the intent-to-treat analyses. For both scales, participants in the illness self-management program improved significantly more than those in the control group.

The supplemental investigation into the lower-than-expected rate of exposure found that participants who attended fewer program sessions tended to feel that the course materials, their classmates, or both were beneath their intellectual or educational level. Post hoc statistical analyses revealed that unexposed participants reported a higher level of knowledge about their psychiatric illness than exposed participants at baseline (t=3.36, df=46, p=.002) on the item tapping this on the client IMRS. Six program participants who had the maximum score on this same scale item at baseline had also completed a bachelor degree or higher level of education; five of these six apparently high-functioning participants attended fewer than three program classes.

Discussion

This is the second randomized controlled trial of the illness management and recovery program ( 6 ) and the first conducted in the United States. Overall, the pattern of results provides additional support for the effects of the program on people with serious mental illness. As in the other controlled study, program participants demonstrated significant improvements in both their own self-reports of illness self-management and in the evaluations of their case manager on the IMRS.

This study went beyond the other controlled trial of the program by including blinded interview-based assessments of symptomatology and psychosocial functioning. Assessments in both of these areas indicated statistically significant treatment effects favoring the program. Specifically, program participants improved significantly more in functioning on the QLS-A and reported less anxiety and depression and less overall symptom severity over time on the BPRS compared with individuals in the control group. The findings suggest that the program can improve the ability of people with serious mental illness to manage persistent symptoms. In addition, the program's emphasis on setting and pursuing personal goals may result in a broader impact on psychosocial functioning, as reflected in improvements in domains of quality of life, including instrumental functioning, interpersonal relationships, and intrapsychic foundations such as having a sense of purpose. Future research should evaluate whether participation in the program influences individual's perceptions of recovery ( 31 ) and self-stigma ( 32 ) of mental illness.

Although program participants showed statistically significantly greater improvement in symptoms than those in the control group, there was no statistically significant difference between the groups in self-ratings of distress on the MCSI. However, participants in the program and those in the control group showed significant reductions in self-reported distress over time, suggesting that the usual services they were receiving may have contributed to improved coping. The difference in findings between interview-based and self-reported symptoms underscores the value of taking a multimodal approach to examining the effects of the program on symptoms and not relying solely on subjective reports of symptom distress.

Program participation was not related to changes in any of the secondary outcomes, including hospitalizations, substance abuse or dependence, suicidal behavior, work, or interest in working. The rate of hospitalization during the year before the study was low for both groups (under 30%) and slightly lower for both groups over the one-year follow-up period (below 20%), suggesting that most participants' psychiatric disorder was well stabilized at the beginning of the study, leaving limited room for improvement. Similarly, at baseline the average scores of participants on the substance use measures were between 1 (no use in the past six months) and 2 (use without impairment over the past six months), indicating few substance problems and little room for improvement. Although there was no statistically significant between-group difference in baseline SBQ-R scores, any potential program effect on suicidality may have been obscured by the substantially greater proportion of program participants than control group participants (33% and 18%, respectively), with baselines at or above the cutoff score for suicidal risk proposed by Osman and colleagues (18). There were no statistically significant differences in work or interest in working between the two participant groups, but employment was not a central focus of the program. The high level of unemployment in the study sample, coupled with participants' strong interest in working—similar to other surveys of persons with serious mental illness ( 33 , 34 )—suggests that these individuals may benefit from access to supported employment ( 35 ) in addition to the illness management and recovery program.

The rate of attendance at the program class sessions was somewhat lower than expected, and focus groups and individual interviews were conducted with participants who attended fewer sessions or dropped out. These qualitative evaluations pointed to one theme among the participants who attended fewer class sessions: they felt the program curriculum and the other participants were below their level of education and knowledge. Post hoc analyses were consistent with these concerns in that participants who attended less than half of the scheduled program sessions scored higher at baseline on the self-reported question about knowledge of mental illness on the client IMRS than participants who attended more than half of the sessions, and knowledgeable, highly educated participants had particularly low attendance. These findings suggest that there may be merit in conducting separate program classes for higher-functioning participants or those with higher levels of psychiatric knowledge and educational attainment.

A number of limitations of the study should be noted. First, the duration of the posttreatment follow-up period was relatively brief (six months), limiting the ability to evaluate the longer-term impact of the program on functioning and illness outcomes. Second, the rate of participation in the program was lower than desired, potentially leading to an underestimation of the true effects of the program on illness management and functioning. The importance of this is underscored by the fact that the statistical analyses on the subgroup of clients exposed to the program indicated significantly larger effects favoring the program on illness self-management than the intent-to-treat analyses; the threat of type II error is only increased by the study's relatively small samples. Third, the use of separate analyses for each primary outcome may introduce type I error because of multiple tests, although this concern is partially allayed by the clear pattern of results favoring the program group. Finally, the study used a treatment-as-usual control group, and thus the program's beneficial impact may have been due to nonspecific treatment effects or expectancies; further research is needed to identify the program's critical components.

The study also had several notable strengths. The program was evaluated in a racially, ethnically, and diagnostically diverse population with serious mental illness, in a nonacademic setting, by an agency that provides a broad range of housing supports to this population. Thus the findings may generalize well to other settings serving heterogeneous populations. The study design and execution were rigorous, as indicated by random assignment of participants to program or control groups, documented high fidelity of the program classes to the program model, assessments by interviewers who were blind to treatment assignment, high interrater reliabilities between the assessors, intent-to-treat statistical analyses, and post hoc exploratory analyses to understand the lower-than-expected rate of retention of program participants.

Conclusions

The findings support the clinical utility of the illness management and recovery program for persons with serious mental illness and suggest that future research is needed to better understand its effects in different settings (community mental health centers), the longer-term impact of the program, and its effects on other domains, including participants' perceptions of themselves and experience of recovery.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors express their appreciation to the Robin Hood Foundation for its financial support of this study.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

2. Gingerich S, Mueser KT: Illness management and recovery; in Evidence-Based Mental Health Practice: A Textbook. Edited by Drake RE, Merrens MR, Lynde DW. New York, Norton, 2005Google Scholar

3. Mueser KT, Corrigan PW, Hilton DW, et al: Illness management and recovery: a review of the research. Psychiatric Services 53:1272–1284, 2002Google Scholar

4. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Whitley R, et al: Fidelity outcomes in the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project. Psychiatric Services 58:1279–1284, 2007Google Scholar

5. Mueser KT, Meyer PS, Penn DL, et al: The illness management and recovery program: rationale, development, and preliminary findings. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32(suppl 1):S32–S43, 2006Google Scholar

6. Hasson-Ohayon I, Roe D, Kravetz S: A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of the illness management and recovery program. Psychiatric Services 58:1461–1466, 2007Google Scholar

7. New York State Office of Mental Health: 2000 New York State Chartbook of Mental Health Information. Available at www.omh.state.ny.us/omhweb/chartbook/text.htm . Accessed on July 9, 2008 Google Scholar

8. Mueser KT, Gingerich S: Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) Scales; in Measuring the Promise: A Compendium of Recovery Measures, Vol 2. Edited by Campbell-Orde T, Chamberlin J, Carpenter J, et al. Cambridge, Mass, Human Services Research Institute, Evaluation Center, 2005Google Scholar

9. Hasson-Ohayon I, Roe D, Kravetz S: The psychometric properties of the Illness Management and Recovery Scale: client and clinician versions. Psychiatry Research 160:228–235, 2008Google Scholar

10. Salyers MP, Godfrey JL, Mueser KT, et al: Measuring illness management outcomes: a psychometric study of clinician and consumer rating scales for illness self management and recovery. Community Mental Health Journal 43:459–480, 2007Google Scholar

11. Bilker WB, Brensinger CM, Kurtz MM, et al: Development of an abbreviated schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale using a new method. Neuropsychopharmacology 28:773–777, 2003Google Scholar

12. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WTJ: The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenia deficit syndrome. Schizophrenia Bulletin 10:388–396, 1984Google Scholar

13. Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J: Manual for the expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:594–602, 1986Google Scholar

14. Shern D, Lee B, Coen A: The Colorado Symptom Inventory: A Self-Report Measure for Psychiatric Symptoms. Tampa, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, 1996Google Scholar

15. Velligan D, Prihoda T, Dennehy E, et al: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale Expanded Version: how do new items affect factor structure? Psychiatry Research 135:217–228, 2005Google Scholar

16. Boothroyd RA, Huey JC: The psychometric properties of the Colorado Symptom Index. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 35:370–378, 2008Google Scholar

17. Conrad KJ, Yagelka JR, Matters MD, et al: Reliability and validity of a Modified Colorado Symptom Index in a national homeless sample. Mental Health Services Research 3:141–153, 2001Google Scholar

18. Osman A, Bagge CL, Gutierrez PM, et al: The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R): validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment 8:443–454, 2001Google Scholar

19. Mueser KT, Noordsy DL, Drake RE, et al: Integrated Treatment for Dual Disorders: A Guide to Effective Practice. New York, Guilford, 2003Google Scholar

20. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Clark RE, et al: Assertive community treatment for patients with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorder: a clinical trial. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:201–215, 1998Google Scholar

21. Essock SM, Mueser KT, Drake RE, et al: Comparison of ACT and standard case management for delivering integrated treatment for co-occurring disorders. Psychiatric Services 57:185–196, 2006Google Scholar

22. Toolkit for Developing and Operating Supportive Housing. Washington, DC, Corporation for Supportive Housing, Mar 31, 2006. Available at www.csh.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=Page.ViewPage&PageID3647 Google Scholar

23. Gingerich S, Mueser KT: Illness Management and Recovery, rev ed. Concord, NH, West Institute, 2006Google Scholar

24. Gingerich S, Mueser KT: Illness Management and Recovery Implementation Resource Kit. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, 2004Google Scholar

25. Verbeke G, Molenberghs G: Linear Mixed Models for Longitudinal Data. New York, Springer, 2000Google Scholar

26. Verbeke G, Molenberghs G (eds.): Linear Mixed Models in Practice: A SAS-Oriented Approach. New York, Springer, 1997Google Scholar

27. Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang K-Y, et al: Analysis of Longitudinal Data, 2nd ed. Oxford, United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, 2002Google Scholar

28. Little RJA, Rubin DB: Statistical Analysis With Missing Data, 2nd ed. New York, Wiley, 2002Google Scholar

29. Conover WJ: Practical Nonparametric Statistics, 3rd ed. New York, Wiley, 1999Google Scholar

30. Satterthwaite FE: An approximate distribution of estimates of variance components. Biometrics Bulletin 2:110–114, 1946Google Scholar

31. Ralph RO, Corrigan PW (eds): Recovery in Mental Illness: Broadening Our Understanding of Wellness. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2005Google Scholar

32. MacInnes DL, Lewis M: The evaluation of a short group programme to reduce self-stigma in people with serious and enduring mental health problems. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 15:59–65, 2008Google Scholar

33. Mueser KT, Salyers MP, Mueser PR: A prospective analysis of work in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:281–296, 2001Google Scholar

34. Rogers ES, Walsh D, Masotta L, et al: Massachusetts Survey of Client Preferences for Community Support Services (Final Report). Boston, Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 1991Google Scholar

35. Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR: An update on randomized controlled trials of evidence-based supported employment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 31:280–290, 2008Google Scholar