Perceived Need for Treatment for Alcohol Use Disorders: Results From Two National Surveys

Alcohol use disorders (abuse and dependence) are common, occurring in 4% to 9% of the U.S. population in a given year ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ), and cause substantial morbidity ( 5 ), accounting for about 5% of all disability ( 6 ). The negative social and health consequences associated with alcohol use disorders are protean ( 7 ) and include increased suicidal behaviors ( 8 , 9 ), high rates of criminal justice involvement and violence ( 10 ), and substantial medical and physical consequences ( 7 , 11 ). The medical consequences of alcohol use disorders, such as cirrhosis and premature death, are particularly high among Hispanics, Native Americans, and African Americans, compared with whites ( 12 , 13 ).

Despite widespread public skepticism regarding treatment services for alcohol use disorders, there are effective, evidence-based psychosocial and pharmacological treatments for alcohol use disorders. These include brief primary care interventions and interventions based on motivational interviewing ( 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ). As with other areas in medicine, actual treatment may not be of high quality or concordant with guidelines ( 20 , 21 ). Treatments for alcohol use disorders are as effective as those for other chronic conditions, including heart disease, asthma, and diabetes ( 22 ), although many individuals experience remission of their alcohol use disorders without formal treatment. It has been suggested in an Institute of Medicine monograph that improving the quality of treatment for alcohol use disorders and other behavioral health disorders would decrease the mortality, morbidity, and societal costs of these disorders ( 20 ).

However, a large majority of individuals with alcohol use disorders receive no treatment for their disorders ( 2 ). A major reason for this may be that individuals with alcohol use disorders do not perceive a need for treatment ( 23 , 24 , 25 ); in the 1992 National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey only 12.7% of persons with alcohol use disorders perceived a need for treatment ( 23 ). This is not surprising, because a hallmark of alcohol use disorders is denial.

Thus it is likely that not perceiving a need for treatment for alcohol use disorders is often a rate-limiting step in receiving treatment. Further, perceived need is potentially modifiable through educational efforts, which could occur anywhere from the clinician-patient interaction to population-level-media efforts, as has occurred with direct-to-consumer advertising for antidepressants.

Although there has been considerable research in the past 15 years to improve detection tools for alcohol use disorders and develop brief primary care interventions for alcohol use disorders ( 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ), we do not know whether rates of perceived need for treatment for alcohol use disorders are increasing over time. In addition, the determinants of perceiving a need for treatment are not well understood. If we better understood the determinants we could possibly use this information to design educational efforts to enhance awareness of alcohol use disorders and increase perceived need for treatment services for alcohol use disorders in at-risk populations. Using data from the National Comorbidity Survey, Mojtabai and colleagues ( 26 ) found that males, persons who are married, those who are uninsured, those who are younger (ages 15 to 24), and those with less severe psychiatric illness were less likely than their respective comparison groups to perceive a need for treatment services for substance use disorders or mental disorders. In our analysis of Health Care for Communities data, men, elderly persons, those with less education, and those who were married were less likely than their respective comparison groups to perceive a need for any treatment services for substance use disorders or mental disorders ( 27 ). However, because the determinants of need for any treatment services for substance use disorders or mental disorders were studied as a single outcome in both of these studies and because perceived need for mental health treatment is greater than the perceived need for treatment of substance use disorders, the extent to which these results can be extrapolated to perceived need for treatment for drug use or alcohol use disorders is unknown.

In this study we had two objectives. First, we sought to provide updated estimates of the percentage of individuals with alcohol use disorders who perceived a need for treatment, and among those, the percentage who actually utilized any treatment for alcohol use disorders. And second, we sought to investigate the determinants of perceived need for and utilization of treatment services for alcohol use disorders. Although past studies have looked at substance use and mental health disorders together as determinants of need, we were particularly interested in conducting a more detailed analysis of the effects of individual symptoms of alcohol use disorders, because we were interested in whether certain symptoms made individuals with alcohol use disorders more likely to perceive a need for treatment. Further, we were interested in comparing the overall explanatory power of sociodemographic factors versus clinical factors in explaining perceived need.

To investigate these issues we used two large national surveys, the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Several characteristics of these studies make them ideal for our purposes. First, investigating the determinants of perceived need for treatment services for alcohol use disorders requires large samples, because perceived need for treatment services for alcohol use disorders is an infrequent event in the general population: alcohol use disorders occur in about 5% to 10% of the population, and in past studies, among individuals with alcohol use disorders, perhaps 10% to 15% perceive a need for treatment. Second, they are nationally representative. Third, they have detailed measures of clinical need, along with sociodemographic measures.

Methods

Sample

The NESARC was conducted by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) in 2001–2002 to provide data for the adult U.S. population on alcohol and drug use, abuse and dependence, and associated psychiatric and physical comorbidities ( 2 ). Potential respondents were selected by multistage probability sampling from the Census 2000–2001 Supplementary Survey and the Census 2000 Group Quarters Inventory. NESARC had a sample of 43,093 individuals in private residences and certain types of group housing and a response rate of 81%. NESARC oversampled Hispanics, non-Hispanic blacks, and younger adults (age 18 to 24). Face-to-face interviews were conducted by trained lay interviewers from the Census Bureau.

The NSDUH is an annual survey sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) ( 28 , 29 , 30 ) to provide national data on the incidence and prevalence of illicit drug, alcohol, and tobacco use. Each year roughly 80,000 individuals are selected by multistage probability sampling to be representative of the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population aged 12 and older. Face-to-face interviews are conducted. Data from the 2004 and 2005 surveys were used for this study.

The response rate for the 2004 survey was 75%, with a total sample of 67,760 individuals. In 2004 a split-sample design was implemented, where adult respondents were divided into two samples. Adults in sample A were administered the Adult Mental Health Module but not the Adult Depression Module. Adults in sample B were administered the Adult Depression Module but only six core questions from the Adult Mental Health module. For this study, sample B was used. The overall response rate for the 2005 sample was 74.4%, with a total sample of 68,308.

Because we were interested in investigating the determinants of perceived need for alcohol treatment services among adults, we limited our samples to adults (age 18 and older) who met criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence in the past year (N=3,305 for NESARC and N=7,009 for NSDUH). The study was approved by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Dependent variables. In NESARC, respondents were classified as having 12-month perceived need for alcohol treatment if they either reported thinking they should have received treatment but did not go or reported receiving treatment in the past 12 months. This is similar to the definition Mojtabai and colleagues ( 26 ) used in his definition of perceived need for alcohol, drug, and mental health problems. To determine perceived unmet need, the respondents were asked "Was there ever a time you thought you should see a doctor, counselor, or other health professional or seek any other help for your drinking, but you didn't?" Respondents needed to also affirm that this perceived need happened in the past 12 months.

To determine receipt of treatment in the past 12 months, the respondent was asked about seeking treatment from the following 13 sources: Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics or Cocaine Anonymous; family services or other social service agency; alcohol or drug detoxification ward or clinic; inpatient ward of a psychiatric or general hospital or community mental health program; outpatient clinic, including outreach programs and day or partial patient programs; alcohol or drug rehabilitation program; emergency room for any reason related to drinking; halfway house, including therapeutic communities; crisis center for any reason related to drinking; employee assistance program; clergyman, priest, or rabbi for any reason related to drinking; private physician, psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, or other professional; or any other agency or professional.

The NSDUH measure of perceived need for alcohol treatment was derived in a similar fashion: first, whether in the past 12 months the respondent reported a need for treatment or counseling or additional treatment or counseling for alcohol use or, second, whether the respondent reported receiving treatment or counseling in the past 12 months for alcohol use at an inpatient hospital, residential drug or alcohol rehabilitation center, outpatient drug or alcohol rehabilitation facility, outpatient mental health center or facility; emergency room, private doctor's office, prison or jail, or a self-help group.

Independent variables. NESARC utilizes the NIAAA Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV), a structured interview designed to be administered by lay interviewers. Studies have demonstrated generally good to excellent reliability and validity ( 2 , 31 , 32 , 33 ). The alcohol diagnostic section from NESARC contains 35 questions to assess the seven alcohol dependence criteria and the four abuse criteria. Thus there are multiple questions for each dependence and abuse criterion.

For each set of questions corresponding to a particular dependence or abuse criterion the number of affirmative responses was summed. For example, in NESARC respondents were asked four questions for the tolerance to alcohol criterion, and thus they could endorse zero, one, two, three, or four alcohol tolerance symptoms. These different levels were then coded with binary indicator variables. To create a more parsimonious model (decrease the number of degrees of freedom) for these abuse and dependence symptoms, when odds ratio (OR) estimates were similar for two values, they were collapsed into fewer categories. For example, the symptom count for tolerance to alcohol was entered into the final model as zero, one or two, or three or more symptoms.

In NSDUH each alcohol and abuse criterion was generally assessed with a single question, which was coded with a binary indicator in our analyses. The use of a single question (rather than multiple questions) for each criterion could be seen as a limitation, although many sophisticated, validated instruments used for research and clinical care for behavioral disorders utilize only one question to assess each criterion.

The NESARC AUDADIS-IV instrument contains measures of 12-month and lifetime mental disorders: major depression, dysthymia, mania and hypomania, generalized anxiety, panic disorder (with and without agoraphobia), agoraphobia without panic disorder, social phobia, specific phobias, posttraumatic stress disorder, retrospective childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and self-report of schizophrenia or psychosis. For our analyses we utilized measures of the number of mental disorders in the past 12 months (zero, one, two, or three or more). Personality disorders included paranoid, schizoid, antisocial, histrionic, avoidant, dependent, and obsessive compulsive. We coded the presence of a cluster A personality disorder (paranoid or schizoid), the presence of a cluster B personality disorder (antisocial or histrionic), and cluster C personality disorder (avoidant, dependent, or obsessive-compulsive) with binary indicators.

The K6 is a measure of psychological distress that was developed for use in the National Health Interview Survey and subsequently included in the NSDUH ( 34 , 35 ). The K6 includes six questions that measure on a 0-to-4 scale how frequently respondents experience symptoms of psychological distress (nervousness, hopelessness, restlessness, feeling depressed, feeling worthless, or feeling that everything is an effort) during the month in the past year when they were feeling their worst emotionally. Respondents with scores of 13 and higher based on a simple count of the endorsed items are considered to have serious psychological distress ( 28 , 29 ). NSDUH also contains a depression module, which allows for the construction of a variable measuring major depression in the past 12 months.

Sociodemographic variables included gender, age, race, income, education, marital status, and insurance status.

Analysis

Our analytical plan was identical in the NESARC and NSDUH samples. First, we used a logistic regression to assess the effects of our predictors on perceived need. The analytical sample was individuals with a diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence. Then among those with perceived need, we regressed any alcohol treatment on the same set of predictors. To measure strength of association, we used the generalized coefficient of determination (R 2 ) described by Cox and Snell ( 36 ).

Results

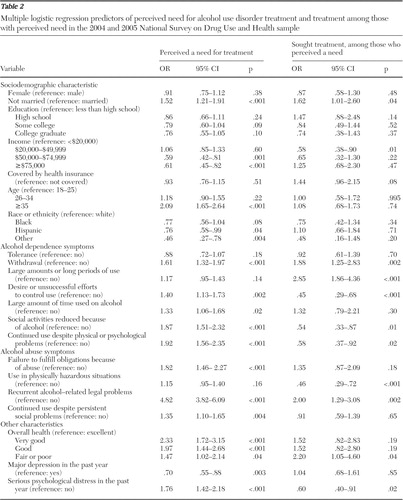

NSDUH

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the NSDUH sample. In NSDUH 10.4% of individuals with alcohol use disorders had any perceived need for treatment in the past year ( Table 1 ). Table 2 shows the multivariate predictors of any perceived need. In a multiple logistic regression, the explanatory power of the diagnostic variables (partial pseudo-R 2 =.13) was much greater than the explanatory power of the demographic variables (partial pseudo-R 2 =.01). Five of the seven dependence criteria and three of the four abuse criteria significantly predicted perceived need, and the results were generally highly significant (that is, p<.001). The effect of each symptom was moderate to strong (that is, ORs greater than 1.30). The strongest predictor of perceived need was recurrent alcohol-related legal problems (OR=4.82, 95% CI=3.82–6.09, p<.001). Symptoms not related to perceived need were tolerance to alcohol, alcohol taken in larger amounts or over a longer period of time than intended, and recurrent use of alcohol in situations where it is physically hazardous. Individuals with serious psychological distress were more likely than those without such distress to perceive need (OR=1.76, CI=1.42–2.18, p<.001). Among the sociodemographic variables, race was a significant predictor of perceived need ( χ2 =16.1, df=3, p=.001), with whites having the highest rates of perceived need. Individuals with low income ( χ2 =23.2, df=3, p<.001) and those who were unmarried (OR=1.52, CI=1.21–1.91, p<.004) were more likely than their respective comparison groups to have perceived need. Age was a highly significant predictor of need ( χ2 =42.9, df=2, p<.001); perceived need increased with age. Gender, education, and insurance status were not significant.

|

|

Among those with perceived need in NSDUH, 70% (weighted) reported receiving any treatment in the past 12 months. Again, in a multiple logistic regression, clinical factors had the greatest explanatory power (partial pseudo-R 2 =.13), compared with sociodemographic characteristics (partial pseudo-R 2 =.03). In the logistic regression, among the diagnostic symptoms, two of the seven dependence criteria and one of the four abuse criteria were positively and significantly associated with receiving treatment, and three of the dependence criteria and one of the abuse criteria were negatively and significantly associated with receiving treatment. Individuals with low income ( χ2 =13.1, df=3, p=.004) were less likely than their respective comparison groups to receive treatment, and individuals who were not married were more likely than those who were to receive treatment (OR=1.62, CI=1.01–2.60, p=.04). Gender, education, race, marital status, and age were not significant predictors of receiving treatment.

NESARC

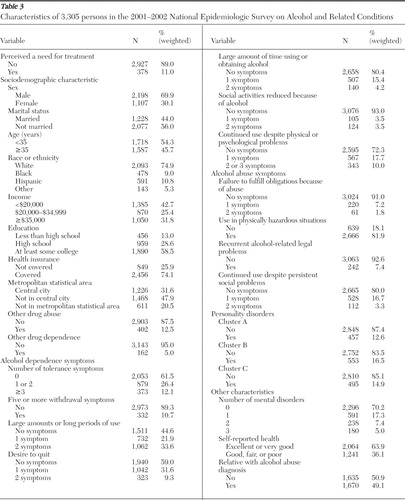

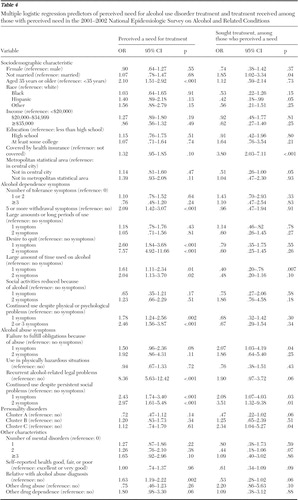

Table 3 shows the characteristics of the NESARC sample. Similar to the NSDUH findings, in NESARC a small percentage of individuals with alcohol use disorders in the past year perceived a need for alcohol treatment (11.0%) ( Table 3 ). Also, as with findings from NSDUH, in a logistic regression investigating perceived need in NESARC, diagnostic factors had the greatest explanatory power (partial pseudo-R 2 =.20), compared with demographic factors (partial pseudo-R 2 =.01). In the logistic regression most of the abuse and dependence symptom variables were significant ( Table 4 ). The following diagnostic factors were not significant predictors of perceived need: tolerance, drinking in larger quantities or for longer periods than anticipated, reduced social activities from alcohol use, failure to fulfill role obligations, and recurrent use in which it was physically hazardous. On the other hand, among the sociodemographic factors, age was the only significant predictor, with younger individuals significantly less likely than older individuals to perceive a need for treatment ( χ2 =19.7, df=1, p<.001). Race, which was significant in our NSDUH analyses, was not significant in our NESARC analyses. Gender, income, education, insurance, marital status, urbanicity, and self-rated health were all also nonsignificant.

|

|

In NESARC, among those with perceived need, 64% (weighted) reported receiving some treatment for alcohol use disorders in the past year. Again, diagnostic factors had the greatest explanatory power (partial pseudo-R 2 =.14), compared with sociodemographic factors (partial pseudo-R 2 =.09). Several sociodemographic groups were significantly less likely than their comparison groups to receive treatment, including persons without insurance, Hispanics, and those who were married.

Discussion

We used two different nationally representative surveys to investigate perceived need for treatment services for alcohol use disorders. Taking into consideration the methodological differences inherent across all surveys, the similarity in the results between the two studies is striking. In both surveys we found that fewer than one in nine individuals with alcohol use disorders perceived a need for treatment. Further, we used a liberal definition of perceived need, based on whether the individual reported thinking he or she needed treatment in the past year or whether treatment was actually received. It likely included individuals in treatment not because they felt they needed treatment but at the behest of family, friends, or the legal system. In both surveys we found that the explanatory power of diagnostic variables was substantially larger than the explanatory power of sociodemographic factors.

The issue of improving treatment for alcohol use disorders and other behavioral health conditions has received considerable attention, including a recent report from the Institute of Medicine ( 20 ). It has been suggested that improving the quality of treatment for alcohol use disorders (and other substance use and mental disorders) could decrease the mortality, morbidity, and societal cost of these disorders. However, because a large majority of individuals with alcohol use disorders receives no treatment at all, improving the quality of care for alcohol use disorders while not increasing the proportion of individuals who receive services might have only a modest impact on morbidity, mortality, and societal costs on the population level.

Our results suggest that the user's failure to perceive need continues to be the major reason that individuals with alcohol use disorders do not receive treatment, because only a small proportion of individuals with alcohol use disorders perceived need. On the other hand, among those with perceived need, a majority received treatment. Further, our results offer little reason for optimism concerning perceived need, because the percentage of persons with perceived need in the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey (NLAES), which was conducted in the early 1990s, was slightly higher than the percentage we found, indicating no progress on this important front.

Factors related to access to alcohol treatment, such as insurance parity for the treatment of substance use disorders, have received considerable attention in the past decade. One concern is that lack of parity contributes significantly to unmet need. However, in our analyses, insurance status did not predict perceived need, but it did predict receiving treatment only among the relatively few who actually perceived a need for treatment. This suggests that attempts to make treatment services for alcohol use disorders more accessible through efforts such as parity legislation will at best increase modestly the number of individuals receiving treatment services for alcohol use disorders. However, this should not be seen as a reason not to implement parity. On the other hand, our results suggest that even modest success in increasing the percentage of individuals with perceived need would dramatically increase the number of individuals in treatment. For example, currently more than eight out of nine individuals do not perceive a need for a treatment. Thus, if efforts to increase perceived need were successful for one out of eight individuals, the overall number of people receiving treatment services for alcohol use disorders could almost double, an increase that would likely overwhelm the capacity of the treatment system for alcohol use disorders. Because of this, if efforts to increase perceived need were successful, either treatment would have to be better targeted to those with the most severe disorders or the capacity of the treatment system for alcohol use disorders would need to be expanded.

The proportion of individuals with alcohol use disorders who perceive a need for treatment could be increased in several ways. First, in a situation where individuals do not perceive a need for treatment, primary care screening, as recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force ( 37 ), is essential in detecting disorders. For policy purposes, it is important to know what proportion of individuals is screened; if screening rates are already high, then there may be little room for improvement. Unfortunately, screening rate estimates of alcohol use disorders in primary care settings vary widely. Clinician surveys suggest that screening occurs frequently ( 38 , 39 ); patient surveys offer less reason for optimism ( 40 , 41 , 42 ). However, studies that indicate that about half of primary care patients with alcohol abuse or dependence are known by the clinician to have an alcohol problem ( 43 , 44 , 45 ) suggest that patient surveys might be more accurate than physician surveys. Similarly, it is important to know whether screening rates are increasing, decreasing, or static, but we know of no study that assesses this important question.

Clinical studies suggest that approximately half of the patients with a mental health or substance use disorder who are recognized by their clinician as having a disorder receive treatment ( 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ), although the proportion receiving guideline-concordant treatment is likely lower. Thus screening does not necessarily lead to high-quality care. Primary care screening could be followed by brief primary care alcohol interventions or specialty referrals for those with relatively severe disorders. The development of screening instruments and brief interventions has been the subject of intense research efforts in the past 15 years, although most efforts have focused on efficacy and effectiveness studies. We believe that the next logical step is to develop efforts that will widely implement these evidence-based screening and brief interventions in community settings.

Along with efforts to increase screening, we also need more effective public health efforts to increase perceived need on a population basis among individuals with alcohol use disorders and their families. Although we know of no experimental data on this issue, such efforts appear to have been effective for depression. For example, use of antidepressants increased dramatically during the 1990s ( 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 ), and it is believed that direct-to-consumer advertising both increased recognition of the symptoms of depression and diminished stigma associated with the disease, resulting in higher treatment rates ( 53 ).

However, increasing perceived need among individuals with alcohol use disorders is likely to be more difficult than increasing perceived need for depression treatment. First, although there are medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of alcohol use disorders (for example, acamprosate, naltrexone, and disulfiram), there has been no significant direct-to-consumer advertising for these products or even detailing to physicians. Second, the stigma associated with alcohol use disorders may be greater than that related to depression. Third, alcohol use disorders are addictive disorders, whereas depression is not.

It would be useful to know which sociodemographic groups are most likely not to perceive a need for treatment, in order to better target these groups with appropriate interventions. We found that in both NSDUH and NESARC the explanatory power of the sociodemographic variables in predicting perceived need was relatively small, especially compared with the explanatory power of the diagnostic variables. Age was the only significant sociodemographic predictor of perceived need in both NSDUH and NESARC, although all sociodemographic groups had high levels of not perceiving need for treatment. This suggests that efforts to increase rates of perceived need should be targeted broadly to all sociodemographic groups, although the problem of perceived need is particularly acute among younger individuals.

NESARC and NSDUH are both ongoing studies and thus are valuable for assessing the evolution of perceived need. Repeated cross-sectional waves, as employed in NSDUH, are the preferred methodology for assessing whether a belief or characteristic, such as perceived need, is increasing over time in a population ( 56 ). On the other hand, the panel design of the NESARC survey will allow us to investigate how perceived need for treatment changes among individuals over time. However, neither survey is able to give us detailed insight into the important issue of why individuals do not perceive need for treatment, an issue that we believe is best addressed initially with qualitative interviews.

Conclusions

It is likely that high levels of unmet need for treatment services for alcohol use disorders will continue to persist as long as perceived need is low. Efforts are needed both to increase levels of perceived need among those with alcohol use disorders and to improve the quality of care they receive.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by grant R01-AA016299 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:617–627, 2005Google Scholar

2. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al: Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:807–816, 2004Google Scholar

3. Summary of Findings from the 2000 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2000Google Scholar

4. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:593–602, 2005Google Scholar

5. Murray C, Lopez A: The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability From Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Boston, Harvard School of Public Health, 1996Google Scholar

6. Murray CJ, Lopez AD: Evidence-based health policy: lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Science 274:740–743, 1996Google Scholar

7. Room R, Babor T, Rehm J: Alcohol and public health. Lancet 365:519–530, 2005Google Scholar

8. Borges G, Walters EE, Kessler RC: Associations of substance use, abuse, and dependence with subsequent suicidal behavior. American Journal of Epidemiology 151:781–789, 2000Google Scholar

9. Conner KR, Hesselbrock VM, Meldrum SC, et al: Transitions to, and correlates of, suicidal ideation, plans, and unplanned and planned suicide attempts among 3,729 men and women with alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 68:654–662, 2007Google Scholar

10. Special issue: Alcohol and Violence. Alcohol Research and Health 25:1–79, 2001Google Scholar

11. McGinnis JM, Foege WH: Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA 270:2207–2212, 1993Google Scholar

12. Plan to Address Health Disparities Initiatives. Bethesda, Md, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2006. Available at pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/HealthDisparities/Strategic.html Google Scholar

13. Caetano R: Alcohol-related health disparities and treatment-related epidemiological findings among whites, blacks, and Hispanics in the United States. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 27:1337–1339, 2003Google Scholar

14. Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, et al: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 1992Google Scholar

15. Walsh DC, Hingson RW, Merrigan DM, et al: The impact of a physician's warning on recovery after alcoholism treatment. JAMA 267:663–667, 1992Google Scholar

16. Wallace P, Cutler S, Haines A: Randomised controlled trial of general practitioner intervention in patients with excessive alcohol consumption. British Medical Journal 297:663–668, 1988Google Scholar

17. Fleming MF, Barry KL, Manwell LB, et al: Brief physician advice for problem alcohol drinkers: a randomized controlled trial in community-based primary care practices. JAMA 277:1039–1045, 1997Google Scholar

18. Fleming MF, Mundt MP, French MT, et al: Brief physician advice for problem drinkers: long-term efficacy and benefit-cost analysis. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 26:36–43, 2002Google Scholar

19. Miller WR, Rollnick S: Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change, 2nd ed. New York, Guilford, 2002Google Scholar

20. Institute of Medicine: Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions. Washington DC, National Academies Press, 2006Google Scholar

21. McLellan AT, Carise D, Kleber HD: Can the national addiction treatment infrastructure support the public's demand for quality care? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 25:117–121, 2003Google Scholar

22. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, et al: Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA 284:1689–1695, 2000Google Scholar

23. Grant BF: Barriers to alcoholism treatment: reasons for not seeking treatment in a general population sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 58:365–371, 1997Google Scholar

24. Falck RS, Wang J, Carlson RG, et al: Perceived need for substance abuse treatment among illicit stimulant drug users in rural areas of Ohio, Arkansas, and Kentucky. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 91:107–114, 2007Google Scholar

25. Wu LT, Pilowsky DJ, Schlenger WE, et al: Alcohol use disorders and the use of treatment services among college-age young adults. Psychiatric Services 58:192–200, 2007Google Scholar

26. Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D: Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:77–84, 2002Google Scholar

27. Edlund MJ, Unützer J, Curran GM: Perceived need for alcohol, drug, and mental health treatment. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 41:480–487, 2006Google Scholar

28. Summary of Findings From the 2003 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Technical Appendices and Selected Data Tables: Vol II. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2004Google Scholar

29. Summary of Findings From the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Technical Appendices and Selected Tables: Vol II. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2002Google Scholar

30. Summary of Findings From the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Rockville, Md, Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2003Google Scholar

31. Hasin D, Carpenter KM, McCloud S, et al: The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a clinical sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 44:133–141, 1997Google Scholar

32. Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, et al: The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 39:37–44, 1995Google Scholar

33. Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, et al: The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression, and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 71:7–16, 2003Google Scholar

34. Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al: Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:184–189, 2003Google Scholar

35. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al: Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine 32:959–976, 2002Google Scholar

36. Cox DR, Snell EJ: Analysis of Binary Data. New York, Chapman and Hall, 1989Google Scholar

37. US Preventive Services Task Force: Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Baltimore, Williams and Wilkins, 1996Google Scholar

38. Friedmann PD, McCullough D, Chin MH, et al: Screening and intervention for alcohol problems: a national survey of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Journal of General Internal Medicine 15:84–91, 2000Google Scholar

39. Bradley KA, Curry SJ, Koepsell TD, et al: Primary and secondary prevention of alcohol problems: US internist attitudes and practices. Journal of General Internal Medicine 10:67–72, 1995Google Scholar

40. Edlund MJ, Unützer J, Wells KB: Clinician screening and treatment of alcohol, drug, and mental problems in primary care: results from Healthcare for Communities. Medical Care 42:1158–1166, 2004Google Scholar

41. D'Amico EJ, Paddock SM, Burnam A, et al: Identification of and guidance for problem drinking by general medical providers: results from a national survey. Medical Care 43:229–236, 2005Google Scholar

42. Deitz D, Rohde F, Bertolucci D, et al: NIAAA's Epidemiologic Bulletin No 34: prevalence of screening for alcohol use by physicians during routine physical examinations. Alcohol Health and Research World 18:162–168, 1994Google Scholar

43. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW: Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA 282:1737–1744, 1999Google Scholar

44. Cleary PD, Miller M, Bush BT, et al: Prevalence and recognition of alcohol abuse in a primary care population. American Journal of Medicine 85:466–471, 1988Google Scholar

45. Buchsbaum DG, Buchanan RG, Poses RM, et al: Physician detection of drinking problems in patients attending a general medicine practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine 7:517–521, 1992Google Scholar

46. Crum RM, Ford DE: The effect of psychiatric symptoms on the recognition of alcohol disorders in primary care patients. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 24:63–82, 1994Google Scholar

47. Shapiro S, German PS, Skinner EA, et al: An experiment to change detection and management of mental morbidity in primary care. Medical Care 25:327–339, 1987Google Scholar

48. Kirmayer LJ, Robbins JM, Dworkind M, et al: Somatization and the recognition of depression and anxiety in primary care. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:734–741, 1993Google Scholar

49. Rumpf HJ, Bohlmann J, Hill A, et al: Physicians' low detection rates of alcohol dependence or abuse: a matter of methodological shortcomings? General Hospital Psychiatry 23:133–137, 2001Google Scholar

50. Mathias SD, Fifer SK, Mazonson PD, et al: Necessary but not sufficient: the effect of screening and feedback on outcomes of primary care patients with untreated anxiety. Journal of General Internal Medicine 9:606–615, 1994Google Scholar

51. Callahan CM, Hendrie HC, Dittus RS, et al: Improving treatment of late life depression in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 42:839–846, 1994Google Scholar

52. Pincus HA, Tanielian TL, Marcus SC, et al: Prescribing trends in psychotropic medications: primary care, psychiatry, and other medical specialties. JAMA 279:526–531, 1998Google Scholar

53. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, et al: National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA 287:203–209, 2002Google Scholar

54. Harman JS, Crystal S, Walkup J, et al: Trends in elderly patients' office visits for the treatment of depression according to physician specialty: 1985–1999. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 30:332–341, 2003Google Scholar

55. Harman JS, Mulsant BH, Kelleher KJ, et al: Narrowing the gap in treatment of depression. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 31:239–253, 2001Google Scholar

56. Murray DM: Design and Analysis of Group-Randomized Trials. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998Google Scholar