Sexuality Among Chinese Mental Health Consumers in Halfway Houses of Hong Kong

Because of the declining average age of mental health consumers in supported residential settings ( 1 ) and the goal of community reintegration of consumers, it is becoming increasingly important to recognize consumers' sexual needs and rights in community settings. Service providers and their agencies must allow appropriate outlets for the expression of these needs. In this study of residents of halfway houses, we explored consumers' sexual needs, sexual attitudes, and sexual expression. Views of both staff and consumers were sought.

Sexuality is an important quality-of-life issue. Previous studies of persons with serious mental illness have indicated high levels of unmet needs for intimate relationships and sexual expression ( 2 , 3 ) that continued to be unmet over time ( 4 ). However, sexual needs among mental health consumers were often assessed broadly by a single item, and their specific sexual needs remained unknown. Sexuality is rarely considered in the psychiatric rehabilitation process, and this lack of attention may be particularly profound among Chinese societies. Past studies have found that Chinese people are generally discouraged to think or to talk about sex. They are socialized to keep these issues within themselves and to respond to sex with feelings of anxiety and shame, rather than with sexual arousal and pleasure ( 5 ).

Rehabilitation services generally overlook the sexual needs of consumers. In one study most consumers with reported needs did not receive help from local psychiatric services or their relatives and friends ( 3 ). Other studies have found that although most rehabilitation professionals can recognize the importance of sexuality as part of the holistic care of patients, they are reluctant to discuss these issues because of inadequate knowledge, insufficient training, lack of time, negative attitudes toward sex, or embarrassment ( 6 , 7 ). Therefore, understanding how staff and consumers differ in their attitudes toward and views of consumers' sexual needs and their expression is an important step in filling this service gap.

The purpose of this study was to explore sexual needs, attitudes, and expression of sexual needs from the perspectives of both staff and consumers in order to inform the development of relevant and effective training programs to ensure that proper attention is paid to consumers' sexuality in community residential settings.

Methods

Participants consisted of 193 Chinese consumers—110 men and 83 women—who had DSM-IV diagnoses of schizophrenia (156 consumers, or 81%) or mood disorders (32 consumers, or 17%). (Data on diagnosis were not available for five consumers.) Also included in the study were 88 multidisciplinary staff—44 men and 44 women—from 11 halfway houses of the largest nongovernmental organization for psychiatric rehabilitation in Hong Kong. Consumers and staff members were recruited by convenience sampling.

To be included in the study consumers had to have a psychiatric diagnosis of any DSM-IV axis I disorder, have normal intelligence, be living in a halfway house, and be able to comprehend questionnaires and complete them independently. Their diagnosis was determined by psychiatrists before intake to the halfway house. Consumers had a mean age of 39.00±9.31 years. Ninety-two participants (48%) had at least a high school education. The mean±SD age at onset of illness was 26.00±8.28 years, and the mean duration of illness was 13.80±9.28 years. All participants were currently taking psychotropic medications.

The mean age of the multidisciplinary staff was 36.00±8.32 years. Forty-one (47%) were professional staff (social workers or nurses), and 46 (52%) were frontline staff without professional degrees. The mean number of years of work experience was 7.00±5.24, and 33 staff (38%) reported having received some form of training in sexuality.

Ethical approval of the study was obtained from the local institutional review board. Data were collected from December 2005 to January 2006. Before data collection, the nature of the study was described to the staff and consumers and their informed consent was obtained. Participants then completed the questionnaire.

Because standardized measures of sexuality of mental health consumers are lacking, the measures for the study were self-constructed. Scale construction was based on measures developed for people with spinal injury ( 7 ) and people with schizophrenia ( 8 ). Before construction of the scale, two staff focus groups were held to gather information about common sex-related activities among consumers. Nine common activities were generated: finding a partner, dating, marriage, procreation, use of sex workers (persons who exchange sex for money), viewing pornography, masturbation, intimate physical contacts, and sexual intercourse. Principal-component factor analysis with varimax rotation revealed a two-factor model that explained 74% of total variance, with factor loadings ranging from .40 to .83. Items 1 to 4 were grouped as relational needs, and items 5 to 9 were grouped as biological needs.

Consumers rated their needs and staff rated their perceptions of consumers' needs on a 5-point Likert scale (Cronbach's α =.88 for consumers' relational needs; .89, for consumers' biological needs; .79, for staff members' perceptions of consumers' relational needs; and .80, for staff members' perceptions of consumers' biological needs).

To assess acceptance of sex-related activities in the halfway house, staff and consumers rated the nine items described above on a 5-point Likert scale. Principal-component factor analysis with varimax rotation showed a two-factor model that explained 78% of total variance, with factor loadings ranging from .39 to .84 (Cronbach's α =.92 for consumers' acceptance of relational activities; .90, for consumers' acceptance of biologically driven activities; .71, for staff members' acceptance of relational activities; and .91, for staff members' acceptance of biologically driven activities).

Staff members' reported sexual knowledge and level of comfort in addressing sexual issues and consumers' reported knowledge and comfort were assessed on a 5-point scale in nine domains: dating and marriage, procreation and pregnancy, contraception, sexual dysfunction, sexually transmitted diseases and AIDS, masturbation, sexual intercourse, sexual harassment, and use of sex workers (Cronbach's α =.91 for consumers' knowledge; .86, for staff members' knowledge; .94, for consumers' comfort; and .96, for staff members' comfort.

The 25-item Sexual Attitude Scale ( 9 ) was used to measure respondents' attitudes toward sexual expression (Cronbach's α =.82 for consumers and .87 for staff). Eight more items specific to consumers were included (for example, "Sexual needs of consumers are similar to those of normal people" and "Because of hereditary factors, consumers should not procreate" (Cronbach's α =.68 for consumers and .72 for staff).

Chi square analyses and t tests were conducted to investigate differences in responses between staff and consumers.

Results

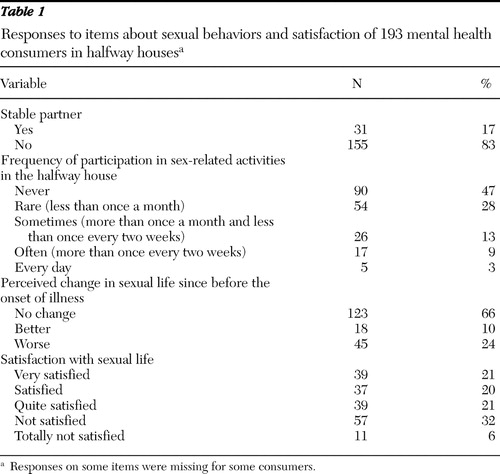

As shown in Table 1 , of the 193 consumers, 83% did not have a stable partner. Nearly half (47%) did not participate in any sex-related activities at the time of study. Sixty-six percent reported that their sexual life had not changed from the time before their illness, 10% reported that their current sexual life was better than before, and 24% felt that it had worsened. Most consumers (62%) were generally satisfied with their sexual life, regardless of whether they were involved in sex-related activities.

|

Forty-three consumers (22%) attributed the changes in their sexual life to changes in their mental state; 36 (19%) attributed the changes to effects of psychiatric medications. Sixty-eight (35%) felt dissatisfied because they were unable to find a suitable partner, and 33 (17%) reported a lack of privacy in residential settings. Eighty-five consumers (44%) reported that they asked halfway house staff for assistance when they encountered sex-related problems, 49 (25%) asked friends, 48 (25%) asked family members, and 34 (18%) asked other consumers. Forty-five (23%) relied on themselves, and 33 (17%) either ignored or avoided the problems.

Fewer than half the consumers (14% to 49%) reported sexual needs in the nine activity areas. However, a relatively higher proportion of staff (31% to 93%) perceived that consumers had sexual needs in these areas. Both consumers and staff rated finding a partner as the greatest need (94 consumers, or 49%, and 81 staff members, or 93%). Need in the area of use of sex workers was the least endorsed need by consumers (27 consumers, or 14%). Among staff, procreation was the least endorsed need for consumers (26 staff members, or 31%). The greatest discrepancy between consumers' needs and staff perceptions of them was in the need for masturbation. Gender differences between consumers and staff are shown in Table 2 . No significant difference was found between consumers with and without schizophrenia.

|

A similar trend was found in acceptance of sex-related activities. Chi square results indicated that for all sex-related activities, a larger proportion of staff than consumers showed acceptance. Nearly half of the consumers felt acceptance about finding a partner (92 consumers, or 48%) and dating (96 consumers, or 50%), which was consistent with the level of acceptance reported by staff. Use of sex workers was the least accepted activity among consumers (39 consumers, or 20%). The least accepted activity among staff was procreation (32 staff members, or 37%). The greatest discrepancy between consumers and staff was found in acceptance of masturbation. Male consumers were more accepting than female consumers of all sex-related activities except procreation. Among staff no significant differences in acceptance of activities were found by gender. No significant differences were found between consumers with and without schizophrenia.

Scores on the Sexual Attitude Scale (SAS) indicated that consumers' attitudes about sexual expression in general were significantly more conservative than those of staff. Both groups were also asked about their attitudes specifically related to sexuality of consumers, and again consumers' attitudes were more conservative. Possible SAS scores (including scores related to specific attitudes about consumers' sexuality) range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating more conservative attitudes. The mean consumer score on general sexual attitudes was 2.97±.58, compared with 2.65±.46 for staff (t=4.64, df=277, p<.001). The mean consumer score on attitudes regarding consumers' sexuality was 2.64±.64, compared with 2.36±.52 for staff (t=3.58, df=277, p<.001). Scores indicated that staff members' ratings of their own sexual knowledge was higher than consumers' ratings of their own knowledge—3.84±.48 for staff and 3.21±.86 for consumers (t=–7.95, df=279, p<.001). Staff members' reported comfort level in addressing consumers' sexual issues was greater than the level reported by consumers—3.95±.70 among staff and 3.03±.95 among consumers (t=–8.10, df=278, p<.001).

In addition, older consumers tended to report a lower level of acceptance of relational activities (r=–.15, p<.05) and biologically driven activities (r=–.16, p<.05) and less frequent participation in sex-related activities (r=–.15, p<.05). Consumers with a longer duration of illness tended to report a lower level of biological need (r=–.15, p<.05) and a lower level of acceptance of relational activities (r=–.17, p<.05) and biologically driven activities (r=–.17, p<.05); they also had more conservative sexual attitudes (r=.19, p<.05) and reported a lower level of sexual knowledge (r=–.20, p<.05) and comfort addressing sexual issues (r =–.15, p<.05).

Discussion

This study explored sexual needs, sexual expression, and sexual attitudes of consumers in halfway houses. Both consumer and staff perspectives were examined. The number of consumers who reported relational needs, such as finding a partner and dating, was larger than the number who reported biological needs, such as using sex workers and viewing pornography. This finding is comparable to past research findings that 40% and 35% of patients with schizophrenia expressed needs in the areas of intimate relationships and sexual expression, respectively ( 3 ). The proportions of consumers reporting sexual needs were similar to the proportions reporting acceptance of sex-related activities.

A possible explanation for the finding that more consumers reported relational needs than biological needs may be that forming intimate relationships is more morally acceptable than using sex for pleasure and fun, particularly in the Chinese culture, which values sex for procreation ( 6 ). Underreporting also may account for this finding, because disclosing biological needs is more embarrassing than disclosing relational needs, particularly in the Chinese culture. Consumers' reluctance to disclose may be evident in the lack of response to some survey items, which ranged from 10% to 30%. Overall, the sample reported a generally low level of need. This may be attributable to consumers' current mental state and medication side effects, which may have led to reduced sexual needs and desires. Male consumers in the sample reported more sexual needs than female consumers and a higher level of acceptance of sexual activities, which is consistent with past research findings ( 10 ).

The discrepancies between staff and consumers were consistent, with staff showing a tendency to overestimate consumers' sexual needs. Staff in community residential settings may not have an accurate and realistic understanding of consumers' sexual needs. Staff members' acceptance of sex-related activities of consumers was higher than consumers' acceptance. The findings are encouraging, because staff members seem to have more liberal sexual attitudes. Staff members also reported a higher level of sexual knowledge and comfort in addressing sexual issues than consumers reported. However, these findings may reflect socially desirable responses.

It is interesting that both staff and consumers reported low levels of acceptance of procreation by consumers. Although the reasons for opposition to procreation by consumers were not examined in this study, we can speculate about possible reasons. First, both groups may have concerns about genetic inheritance of psychiatric problems. Second, parenting is a highly stressful and prolonged activity that requires a substantial amount of financial and personal resources. Residents of halfway houses by definition are not yet ready for independent living. Thus their expressed hesitation is reasonable and may indicate that they are responsible people. It is important to examine reasons behind the opposition to procreation by consumers because it has implications for sexuality training and for contraceptive practices and safer sex.

This study is one of the first empirical attempts to understand issues of sexuality among consumers by exploring the perspectives of both consumers and staff. However, several limitations should be noted. First, because no standardized measures of sexuality were available, most of the measures used in this study were self-constructed. Future studies should develop and validate sexuality measures to facilitate research in this area. In addition, future studies should examine clinical factors, such as symptom severity, that may be correlated with sexual needs, attitudes, and knowledge. Moreover, as consumers become increasingly reintegrated into the community, it is important to examine perceptions of consumers' sexual needs among other groups, such as family members and the general public, and levels of acceptance among these groups.

Conclusions

This study was the first attempt to understand sexual needs, sexual expression, and attitudes toward sexuality among Chinese consumers and staff in community residential settings. Findings suggest that policy changes may be necessary to ensure that systems of care recognize mental health consumers' relational and sexual needs. This may include arranging social activities and restructuring dining or housing arrangements among consumers to broaden their relational circles as well as providing private space in halfway houses. Psychoeducation and training of both consumers and staff are critical in developing positive and open attitudes toward sexuality and in correcting myths and misconceptions about the sexuality of mental health consumers. These structural changes, in addition to good staff-consumer communication, are important in actualizing consumers' rights to express relational and sexual needs.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors thank the staff of the New Life Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association for their assistance in data collection.

The authors report no competing interests

1. Cultivate a Healthy Life, 2004–2005 Annual Report. Kowloon, Hong Kong, New Life Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association, 2006Google Scholar

2. Brunt B, Hansson L: Comparison of user assessed needs for care between psychiatric inpatients and supported community residents. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science 16:406–413, 2002Google Scholar

3. Bengtsson-Tops A, Hansson L: Clinical and social needs of schizophrenia outpatients living in the community: the relationship between needs and subjective quality of life. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:513–518, 1999Google Scholar

4. Wiersma D, Nienhuis FJ, Slooff CJ: Stability and change in needs of patients with schizophrenic disorders: a 15- and 17-year follow-up from first onset of psychosis and a comparison between "objective" and "subjective" assessments of needs for care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:49–56, 1998Google Scholar

5. So HW, Cheung FM: Review of Chinese sex attitudes and applicability of sex therapy for Chinese couples with sexual dysfunction. Journal of Sex Research 42:93–101, 2005Google Scholar

6. Haboubi NHJ, Lincoln N: Views of health professionals on discussing sexual issues with patients. Disability and Rehabilitation 25:291–296, 2003.Google Scholar

7. Kendall M, Booth S, Fronek P, et al: The development of a scale to assess the training needs of professionals in providing sexuality rehabilitation following spinal cord injury. Sexuality and Disability 21:49–64, 2003Google Scholar

8. Raja M, Azzoni A: Sexual behavior and sexual problems among patients with severe chronic psychoses. European Psychiatry 18:70–76, 2003Google Scholar

9. Hudson WW, Murphy GJ, Nurius PS: A short-form scale to measure liberal vs conservative orientations toward human sexual expression. Journal of Sex Research 19: 258–272, 1983Google Scholar

10. Regan PC, Atkins L: Sex differences and similarities in frequency and intensity of sexual desire. Social Behavior and Personality 34:95–102, 2006Google Scholar