Siblings' Coping Strategies and Mental Health Services: A National Study of Siblings of Persons With Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a devastating illness, not only for the person who is ill but also for the entire family. Among the most vulnerable and most affected are siblings. As a consequence of unremitting stress, multiple aspects of their lives are affected, including relationships, roles, and health ( 1 ). Siblings often do not know how to cope with schizophrenia and its impact on their lives. Although the burden is costly for siblings, minimal attention has been paid to coping strategies and mental health services that could reduce the stress they experience.

The literature on coping with schizophrenia from the sibling's perspective is extremely limited. Only a few studies have focused on the resources that siblings of persons with schizophrenia need to manage the demands of the illness. Landeen and colleagues ( 2 ) developed a 14-item questionnaire and assessed the needs of 88 siblings for information, support, and practical skills. The results indicated a desire for more specific information about schizophrenia from providers. Another study of 11 siblings found that families had differing stages of readiness to receive information about the illness. For example, families who did not seek information appeared to be in denial ( 3 ). Gerace and colleagues ( 4 ) interviewed 14 adult siblings and distinguished three coping patterns: collaborative, crisis oriented, and detached. The collaborative siblings were actively involved with providers in caring for their sibling, whereas the detached siblings tried to keep the ill sibling out of their lives. In a recent study, Stalberg and colleagues ( 5 ) also examined coping patterns through interviews with 16 siblings. The major categories of coping were avoidance, isolation, normalization, caregiving, and grieving. Caregiving and isolation were viewed as similar to the patterns identified by Gerace and colleagues ( 4 ).

Some investigators examined the coping strategies and resources utilized both by siblings and offspring of persons with varying psychiatric diagnoses, including schizophrenia ( 6 , 7 , 8 ). Healthy and unhealthy coping skills of ten adult offspring and ten adult siblings of people with mental illness were identified by Kinsella and Anderson ( 8 ). Healthy skills included seeking support from family and friends, acquiring information, and having spiritual faith. Unhealthy coping consisted of withdrawing from the ill family member and addictive behaviors such as drug use.

Very little attention has focused on the role of mental health services in decreasing sibling stress. Nechmad and colleagues ( 9 ) pointed out that a limitation of current sibling research is the lack of recommendations for ways that health care providers can assist in relieving stress. In a study of 20 siblings of persons with mental illness, Riebschleger ( 10 ) reported that siblings recommended inclusion in client treatment, support, and education. Marsh and colleagues ( 7 ) assessed the relative importance of seven sibling needs and found that the most compelling needs were satisfactory services for their relative, working through reactions to the illness, skills for coping, and personal support.

Sibling studies have been limited by lack of sample homogeneity, reliance on qualitative data, and small samples. These limitations make it difficult to understand the efficacy of coping strategies and the relative importance of mental health services from the sibling perspective. Furthermore, in most studies there is no comprehensive framework that ties all aspects of the coping process together.

To investigate the impact of schizophrenia on siblings, we adapted the stress process model developed by Pearlin and colleagues ( 11 ) and developed a comprehensive questionnaire to assess each component of the model ( 12 , 13 ). According to Pearlin and colleagues, coping has protective functions that can be carried out in three ways: managing the situation giving rise to stress, managing the meaning of the situation to reduce threat, and managing the emotional distress created by the situation. Coping strategies represent some of the concrete things people do to deal with the problems they encounter. In addition to coping strategies, social supports, such as family and friends, serve as resources for mediating stress ( 11 , 14 ). Mental health services can also be viewed as a resource in mitigating the impact of stressors ( 15 ).

There is a need for additional research that documents the sibling perspective on coping and mental health services. In turn, this knowledge can serve as the foundation for interventions aimed at relieving stress and increasing the well-being of siblings. This article presents selected survey data from a larger study that examined the impact of schizophrenia on siblings. The purpose of the study reported here was to examine the helpfulness of coping strategies and social supports as well as the relative importance of mental health services from the perspective of siblings of persons with schizophrenia.

Methods

Study sample

Siblings were eligible for the study if they were 18 years or older and had a sibling diagnosed as having schizophrenia. Siblings were recruited through three methods: first, questionnaires were sent to members of the Sibling and Adult Children Council of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI); second, an announcement of the study was included in the NAMI newsletter; and third, presidents of NAMI affiliates were asked to publicize the study at their meetings. Names and addresses of interested siblings were sent to the investigators. A total of 1,254 questionnaires were mailed, and 761 (61%) were returned. Thirty-nine states were represented in the sample. The dates of the study were July 1995 to May 1996. The study was approved by the University of Iowa's Human Subjects Committee, and informed consent was obtained from all respondents. [An appendix showing the respondents' state of residence is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Measures

The conceptual basis, construction, reliability, and construct validity of the Friedrich-Lively Instrument to Assess the Impact of Schizophrenia on Siblings (FLIISS) have been described in earlier work ( 12 , 13 ). The coping and mental health services questions are part of the FLIISS and the focus of this study.

Helpfulness of coping strategies was measured by 22 items that asked siblings to rate the degree of helpfulness from 1, very helpful, to 4, harmful, and a rating of 5 indicates "did not use." Categories of strategies included management of the situation (five items), management of meaning (five items), management of distress (five items), social support (four items), and distancing (three items). Siblings also identified the degree of helpfulness of both informal and formal support from a 12-item list that included family, friends, and mental health providers.

Service needs were assessed with two sets of questions. First, siblings rated the relative importance of 11 needs at the present time from 1, very important, to 3, not important. This measure was an adaptation of the needs scale developed by Marsh and colleagues ( 7 ). Second, the relative importance of mental health services was assessed with 19 questions that included three categories of services: direct services for the ill sibling (nine items), information (six items), and support (four items). Siblings were asked to consider the importance of ways that health care professionals could assist them at the present time. Many of the top-ranked services were added at the suggestion of siblings during the pilot study.

Results

Sample characteristics

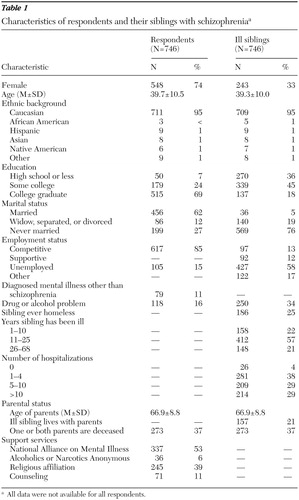

Respondents who answered less than 70% of the questions were not included in this study, leaving a sample of 746 siblings. Characteristics of respondents and ill siblings are exhibited in Table 1 . A majority of the respondents were Caucasian, female, married, college educated, and employed. In contrast, most ill siblings were male, unmarried, and unemployed, and few had graduated from college. Ages for respondents and ill siblings ranged from 18 to 79 years.

|

Siblings had been ill an average of 19.4±10.6 years and had been hospitalized numerous times, including 214 (29%) who had been hospitalized more than ten times. Substance abuse and homelessness were prevalent among ill siblings. Although substance abuse was less common among respondents, one-sixth reported problems with drugs or alcohol and about one-tenth were diagnosed as having a mental illness other than schizophrenia.

The mean age of the siblings' parents was 66.9±8.8 years, and in 273 (37%) of the families one or both parents were deceased. About one-fifth of ill siblings were living with parents. Many respondents were members of NAMI and religious groups, whereas far fewer participated in Alcoholics or Narcotics Anonymous or counseling.

Coping strategies

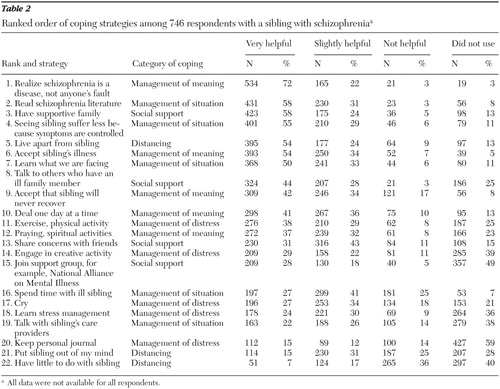

Coping strategies and the proportion of respondents who used them are ranked in order of helpfulness in Table 2 . Management of the illness situation through education and symptom control were some of the most helpful strategies. In contrast, spending time with the ill sibling (ranked 16) and talking with care providers (ranked 19) were very helpful to only about one-fourth of the siblings.

|

Strategies related to management of meaning were highly ranked. The most helpful strategy on the entire scale was "realize schizophrenia is a disease, and not anyone's fault." Accepting the illness and its consequences for the family was also very helpful to a majority of siblings. Family members were a very helpful source of social support to 423 siblings (58%). In addition, talking with others outside the family who had an ill relative was very helpful to 324 (44%).

Strategies for managing personal distress were ranked in the bottom third of those that were very helpful, except for exercise and physical activity (ranked 11). Distancing strategies, other than living in a location apart from the ill siblings (ranked 5), were the lowest ranked. Putting the siblings out of mind and having little to do with the ill siblings were the least helpful strategies.

Support from individuals

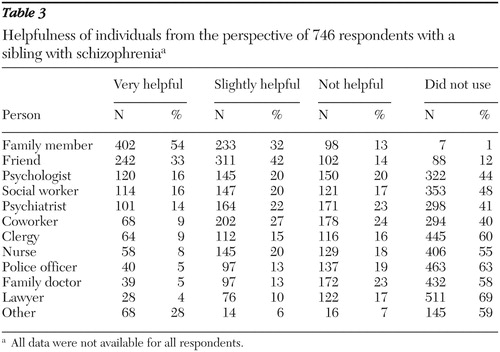

The helpfulness of persons within the informal and formal support systems is listed in Table 3 . A majority of siblings identified their family as very helpful, and about one-third of siblings viewed friends as very helpful. All providers ranked much lower in use and helpfulness. Many did not have any contact with mental health providers, ranging from 298 (41%) for psychiatrists to 406 (55%) for nurses.

|

Current needs and mental health services

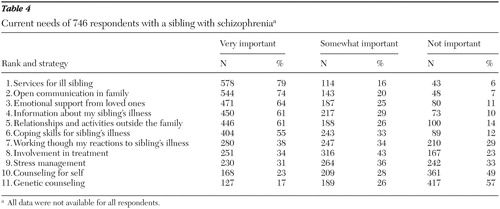

The current needs of the siblings are displayed in Table 4 . The number-one item was services for the ill person, not services for the respondent. Open communication in the family, emotional support, and information about the illness were next in importance. In contrast, the respondents assigned a much lower ranking to stress management skills, individual counseling, and genetic counseling.

|

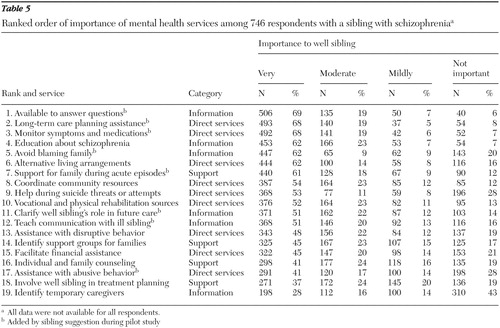

Table 5 lists the relative importance of mental health services in assisting the siblings. Similar to the current needs shown in Table 4 , many of the top-ranked items involved direct services for the ill sibling. The most highly ranked service was assistance with long-term planning for the ill sibling. Other top-ranked services included monitoring symptoms of the illness and medications, identifying alternative living arrangements, coordinating community resources, providing help during suicide threats or attempts, and referring the ill sibling for vocational and psychosocial rehabilitation.

|

In Table 5 , the availability of professionals to answer questions about the ill sibling was rated number one. A majority of siblings also wanted professionals to educate them about schizophrenia without blaming the family as well as to clarify their role in the ill sibling's future care. Support-related services were generally ranked lower than other services and included identifying support groups for families and providing individual or family counseling.

Discussion

One of the most striking findings in our study is that siblings identified services for the ill family member as more important than specific services for themselves. The ill siblings had a difficult time in the community. They had been ill an average of 19.4±10.6 years. Most had a history of multiple hospitalizations, about one-third had a history of substance abuse, and one-fourth had been homeless. These are all factors that significantly increased stress for siblings in this study ( 13 ). Community services are becoming increasingly scarce, as indicated by greater numbers who are homeless and imprisoned ( 16 ). Lack of direct services has serious consequences for the ill person and the sibling. According to a sibling who has a 41-year-old sister with schizophrenia: "My ultimate concern is for my sibling who will die from poor living conditions, which are directly related to her illness…. I've been waiting almost two years for her name to reach the top of a housing list. They tell me it will be about one more year! … If the illness were treated properly, the effect on the sibling would diminish."

Siblings identified symptom control for the ill siblings as one of the most helpful coping strategies as well as a top-ranked service. In previous work we found that siblings who reported more disturbing behavior of their ill relative had significantly more stress in multiple aspects of their lives ( 17 ). Symptoms and behaviors that were the most stressful for siblings included psychotic symptoms, noncompliance, and verbal aggression. These findings support Pearlin's ( 11 ) conceptualization of the importance and impact of primary stressors in his model that include illness symptoms that trigger multiple stress reactions. These findings also lend support to research in which the ill person's psychiatric symptoms and behavioral problems have been consistently observed to be strong predictors of family burden ( 18 , 19 ).

Nearly all of the siblings wanted service providers to assist with long-term planning for the ill sibling and clarify their role in future care. One of the greatest sources of stress for 612 siblings (82%) was "concern about who will take care of the ill sibling when parents no longer can." At the time of the study, respondents provided emotional and social support and helped with crises, but few coordinated the total care ( 20 ). About one in five ill siblings were living with aging parents, and in one-third of the families one or both parents were deceased. Future caregiving for persons with mental illness is emerging as a social problem for which few are prepared ( 21 ). Although siblings are considered the logical replacements for aging parents, it is unclear what their roles will be or how this will impact their lives ( 22 ). Hatfield and Lefley ( 23 ) reported that siblings were more likely to provide social and emotional support than the instrumental support offered by parents. Siblings are in a dilemma: spending time with ill siblings and living with them in the past has significantly increased their stress ( 13 ); however, having little to do with the ill sibling was the least helpful of all coping strategies. These findings underscore the importance of assisting siblings in the development of strategies that will maintain relationships with ill siblings and decrease stress.

Information about the sibling's illness and availability of providers to answers questions were top service needs. Although clinical guidelines for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia recommend that providers share information with families and involve them in treatment, research indicates that collaboration is not part of routine clinical practice ( 24 ). Over the years, siblings have been left out of the treatment process and lack the knowledge and skills needed to manage the illness situation ( 8 ). A sibling wrote, "The worst problem our family has had, and repeatedly, is that during hospitalization (dozen or more) the doctors cannot share information about treatment with the family. My brother is considered an independent adult with privacy rights, even though he is dependent on family and community for support. We are neglected at this crucial time."

Understanding that no one in the family is to blame for causing schizophrenia was the most helpful coping strategy of all. In the past, about one-fourth of these siblings felt guilty because professionals blamed the family for the illness ( 20 ). Torrey ( 16 ) emphasized the importance of a no-blame strategy: "Developing the right attitude is the single most important thing an individual or family can do to survive schizophrenia. The right attitude evolves naturally once there is resolution of the twin monsters of schizophrenia—blame and shame." Accepting the illness is an important ingredient of the right attitude and was acknowledged as being very helpful to siblings in this study as well as earlier studies ( 7 ). Reading literature about schizophrenia helped put the illness in perspective and was also a top-ranked coping strategy.

It is no surprise that social support was a highly ranked coping strategy. Solomon and Draine ( 25 ) noted that social support was the strongest factor in their study in explaining adaptive coping among family members of persons with mental illness. Although their study found that friends and coworkers were helpful, the most helpful of all were family members and others outside their family who also had an ill relative. On the other hand, very few siblings found service providers to be helpful. Siblings with a diagnosed mental illness or substance abuse problems may be in need of more extensive counseling support from providers and referrals to support groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous. When either of these problems was present, siblings experienced more stress in every measured aspect of their lives ( 13 ). Outside of the formal system of care, many siblings found support groups (NAMI) and religious groups to be valuable sources of support.

These findings cannot be generalized because NAMI was the main recruitment source, respondents were primarily college-educated siblings, and almost all respondents were Caucasian. However, these siblings can be considered "best case" examples of the needs of siblings and potential future caregivers.

Conclusions

Before development of the FLIISS, there were no comprehensive measures to assess the breadth and depth of coping strategies and mental health services helpful to siblings of persons with schizophrenia. These quantitative measures allowed siblings to prioritize needs and services, and the large sample strengthened the reliability of the findings. Siblings identified services for the ill family member, including symptom control, adequate housing, and long-term planning, as more important than specific services for themselves. However, in the future, siblings will be faced with the responsibility of being the primary caregiver. This role, combined with dwindling community services, will increase stress for siblings.

The challenge is clear—providers must advocate for adequate services for the ill person, include siblings in long-term planning, and help educate siblings about the illness. Additionally, providers should encourage siblings to seek social support from family, friends, and organizations such as NAMI or religious groups. Decreased stress can not only increase quality of life for siblings of persons with schizophrenia but also help siblings be better prepared to manage the demands of the illness.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by the Nellie Ball Trust Research Fund.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Lively S, Friedrich RM, Buckwalter KC: Sibling perception of schizophrenia: impact on relationships, roles, and health. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 16:225–238, 1995Google Scholar

2. Landeen J, Whelton C, Dermer S, et al: Needs of well siblings of persons with schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:266–269, 1992Google Scholar

3. Main MC, Gerace LM, Camilleri D: Information sharing concerning schizophrenia in a family member: adult siblings' perspectives. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 7:147–153, 1993Google Scholar

4. Gerace LM, Camilleri D, Ayres L: Sibling perspectives on schizophrenia and the family. Schizophrenia Bulletin 19:637–647, 1993Google Scholar

5. Stalberg G, Ekerwald H, Hultman CM: At issue: siblings of patients with schizophrenia: sibling bond, coping patterns, and fear of possible schizophrenia heredity. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:445–458, 2004Google Scholar

6. Marsh DT, Appleby NF, Dickens RM, et al: Anguished voices: impact of mental illness on siblings and children. Innovations and Research 2:25–34, 1993Google Scholar

7. Marsh DT, Dickens RM, Koeske RD, et al: Troubled journey: siblings and children of people with mental illness. Innovations and Research 2:13–23, 1993Google Scholar

8. Kinsella KB, Anderson RA: Coping skills, strengths, and needs as perceived by adult offspring and siblings of people with mental illness: a retrospective study. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 20:24–32, 1996Google Scholar

9. Nechmad A, Fennig S, Ternochiano P, et al: Siblings of schizophrenic patients: a review. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Science 37:3–11, 2000Google Scholar

10. Riebschleger JL: Families of chronically mentally ill people: siblings speak to social workers. Health and Social Work 16:94–103, 1991Google Scholar

11. Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SG: Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist 30:583–594, 1990Google Scholar

12. Friedrich RM, Lively S, Rubenstein L, et al: The Friedrich-Lively Instrument to Assess the Impact of Schizophrenia on Siblings (FLIISS): part I—instrument construction. Journal of Nursing Measurement 10:219–230, 2002Google Scholar

13. Rubenstein L, Friedrich RM, Lively S, et al: The Friedrich-Lively Instrument to Assess the Impact of Schizophrenia on Siblings (FLIISS): part II—reliability and validity assessment. Journal of Nursing Measurement 10:231–248, 2002Google Scholar

14. Pearlin LI, Schooler C: The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 19:2–21, 1978Google Scholar

15. Greenberg JS, Greenley JR, Brown R: Do mental health services reduce distress in families of people with serious mental illness? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 21:40–50, 1997Google Scholar

16. Torrey EF: Surviving Schizophrenia: A Manual for Families, Patients, and Providers. New York, Harper Collins, 2006Google Scholar

17. Lively S, Friedrich RM, Rubenstein, L: The effect of disturbing illness behaviors on siblings of persons with schizophrenia. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association 10:222–232, 2004Google Scholar

18. Greenberg JS, Kim HW, Greenley JR: Factors associated with subjective burden in siblings of adults with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:231–241, 1997Google Scholar

19. Baronet AM: Factors associated with caregiver burden in mental illness: a critical review of the research literature. Clinical Psychology Review 10:819–841, 1999Google Scholar

20. Friedrich RM: Assessing the impact of schizophrenia on siblings: a national study. Presented at the NAMI annual convention, Minneapolis, Minn, June 28–July 1, 2003Google Scholar

21. Lefley HP: Aging parents as caregivers of mentally ill adult children: an emerging social problem. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:1063–1070, 1987Google Scholar

22. Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Orsmond GI, et al: Siblings of adults with mental illness or mental retardation: current involvement and expectation of future caregiving. Psychiatric Services 50:1214–1219, 1999Google Scholar

23. Hatfield AB, Lefley HP: Future involvement of siblings in the lives of persons with mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 41:327–338, 2005Google Scholar

24. Marshall T, Solomon P: Professionals' responsibilities in releasing information to families of adults with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 54:1622–1628, 2003Google Scholar

25. Solomon P, Draine J: Adaptive coping among family members of persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:1156–1160, 1995Google Scholar