How Many Forensic Assertive Community Treatment Teams Do We Need?

Since it was first developed over 30 years ago, assertive community treatment (ACT) has been applied to a variety of populations, problems, and settings and can best be conceptualized as a service system designed to provide treatment and services in an integrated package ( 1 , 2 ). ACT is most effective for persons with severe mental illness—defined by diagnosis, duration, and disability—who are the heaviest users of inpatient psychiatric services ( 3 , 4 ). Heavy users have been defined as those who have a minimum of two hospitalizations in one year, although some studies have used the definition of three hospitalizations in one year. Having clear eligibility criteria enables communities to target those who can benefit the most from ACT and to estimate of the number of ACT teams they might need ( 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ).

Over the past several years, ACT teams in some communities have expanded their focus to preventing jail detentions (that is, forensic assertive community treatment [FACT]) in response to growing concern about the number of persons with severe and persistent mental illness (hereafter referred to as severe mental illness) who are involved with the criminal justice system. In some cases, consumers involved with the criminal justice system are added to existing ACT teams. In other cases, new specialty teams have been developed that serve only consumers involved with the criminal justice system (FACT teams). However, knowledge is not well developed about what, if any, adaptations are needed for ACT to serve consumers involved with the criminal justice system and about the evidence base for FACT in regard to reducing recidivism. In the first national study of FACT programs, a survey of 16 FACT teams from nine states reported that the primary distinction between FACT and ACT is that FACT has the goal of preventing incarceration, rather than just preventing hospitalization ( 9 ). Also, unlike ACT teams that look to local hospitals and mental health agencies to identify their consumers, FACT programs target local jails ( 9 ).

There is mounting evidence suggesting that ACT teams focused on reducing hospitalizations are not effective in reducing jail recidivism ( 6 , 10 , 11 ). However, in separate pre-post studies (no control groups) of small local samples, consumers who received FACT had significant reductions in jail days, arrests, hospital days, and hospitalizations ( 12 , 13 ). Further, one of the largest studies of services for justice-involved consumers occurred in California and involved over 4,000 consumers who were randomly assigned to receive enhanced services—which included FACT, ACT, forensic intensive case management, mental health courts, and in-jail services—or usual care as a part of California's statewide Mentally Ill Offender Crime Reduction Grant (MIOCRG) ( 14 ). Consumers who received enhanced services had fewer arrests, convictions, and jail days, compared with those who received usual care. However, ACT fidelity was positively correlated with better outcomes for only two out of six criminal justice measures—that is, for any booking or conviction over a two-year follow-up period but not for number of bookings, convictions, or jail days or for any jail days. These results do suggest that specialty teams are warranted. However, more rigorous research is needed.

Moreover, the results of these studies are promising, in general, but each study used different eligibility criteria and the studies do not move us closer to a consensus on identifying the target population for FACT. For example, Lamberti and colleagues ( 12 ) used severe mental illness and at least one arrest; McCoy and colleagues ( 13 ) used a history of frequent incarcerations and hospitalizations, with flexibility regarding severity of mental illness; and in the MIOCRG study ( 14 ), provider-specific eligibility criteria were used—that is, some mental illness and some contact or the potential for contact with the criminal justice system.

Several important issues emerge from the literature reviewed above. First, the evidence for FACT is promising, but clearly more research is needed. Second, the target population for FACT is unclear. Third, FACT is being widely disseminated despite its lack of evidence and lack of a clearly defined target population.

ACT is neither appropriate nor cost-effective for all persons with severe mental illness, so it is likely that FACT is neither appropriate nor cost-effective for all persons with severe mental illness who are involved with the criminal justice system. However, eligibility criteria for determining who should receive FACT have not been established. Developing these criteria is an initial and critical step toward growing the evidence base for FACT, and without a clear definition for eligibility, communities will have little guidance with respect to targeting those most in need of FACT and will be challenged to estimate the number of FACT teams they might need. To address these gaps in our knowledge, this brief report proposes a definition for FACT eligibility—severe mental illness and three jail detentions in a one-year period. The study used administrative data from a large, urban county to develop estimates of the number of FACT teams needed.

Methods

This study used 5.5 years (July 1, 1993, through December 31, 1998) of linked, administrative data from a large, urban community in the western United States. Data from the local county mental health authority, local jail, local hospitals, state hospital, and state Medicaid program were accessed and linked in order to track use of outpatient mental health services, state and local hospitals, and jails over the 5.5-year study period.

Approval to conduct this study was obtained from the institutional review boards at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and from the Research and Data Analysis Division of the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services.

The administrative data were used to identify the following groups of people: all public mental health service users; persons who had a serious mental illness, as evidenced by a diagnosis of schizophrenia, affective disorder with some exceptions, delusional disorder or psychosis not otherwise specified; persons with a severe mental illness (that is, diagnosis listed above plus enrollment in Supplemental Security Income or Social Security Disability Insurance); persons with severe mental illness who had three or more hospitalizations within one calendar year; and persons with a severe mental illness who had three or more jail detentions within one calendar year. ACT eligibility was defined as having three or more hospitalizations in a calendar year. FACT eligibility was defined as having three or more jail detentions in a calendar year. Using this definition for FACT eligibility parallels a contemporary definition of ACT eligibility and follows the rationale that if ACT is most appropriately targeted to the heaviest users of hospitals, then FACT would be most appropriately targeted to the heaviest users of jails.

Results

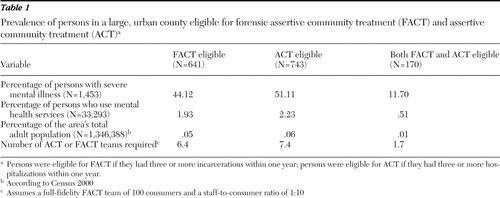

Over the 5.5 year study, 33,293 adult county mental health service users (ages 18–64 years) were enumerated; 51.7% (N=17,204) of these consumers were identified as having a serious mental illness, and 4.4% (N=1,453) were identified as having a severe mental illness. As shown in Table 1 , in this community, 51.1% (N=743) of those identified as having a severe mental illness had three or more hospitalizations in a one-year period and met the eligibility criteria for ACT. Also shown in the table, 44.1% (N=641) of those with a severe mental illness were eligible for FACT. This represents approximately 2% of this community's population of mental health consumers and .05% of this community's adult population ages 18–64 years. It would require approximately 6.4 FACT teams to serve these 641 consumers, assuming a full-fidelity FACT team of 100 consumers and a 1:10 staff-to-consumer ratio. However, it is not uncommon for teams to maintain fewer staff and consumers (that is, six or seven staff members and 60 to 70 consumers), and given this, more teams would be needed to serve these 641 consumers.

|

There was an overlap of 27% (170 out of 641 persons) among the ACT-eligible and 23% (170 out of 743 persons) among the FACT-eligible groups. More specifically, 170 persons had three jail detentions and three hospitalizations in a one-year period. This represents 12.3% of the combined total of 1,384 persons who were eligible for ACT or FACT, approximately .5% of this community's population of mental health users and .01% of this community's adult population ages 18–64. Arguably, these individuals represent those profoundly in need of FACT, and two teams would be needed to serve them.

Table 1 also shows that the percentage of persons with severe mental illness who are eligible for FACT (that is, three or more incarcerations in one calendar year) is slightly less than the percentage of persons with severe mental illness who are eligible for ACT (that is, three or more hospitalizations in one calendar year). So, at least in this community, there are almost as many FACT-eligible persons as there are ACT-eligible persons. Also, 36.7% (N=272) of the 741 ACT-eligible individuals had at least one jail detention (data not shown).

Discussion

The practice of FACT has outpaced its evidence base, and although preliminary evidence is encouraging, there are many unknowns regarding FACT. For example, the limited evidence on FACT suggests that specialty teams are associated with better criminal justice outcomes, compared with nonspecialty teams. However, the reasons why are not fully understood. Other questions involve whether FACT teams can achieve desirable public health and public safety outcomes? What adaptations do FACT teams need to best serve consumers involved with the criminal justice system? How do FACT teams interface with the criminal justice system?

As previously suggested, one remarkable gap in our knowledge is the lack of a clearly defined target population for FACT. Given how little we know about FACT, it may seem premature to propose eligibility criteria and suggest guidelines for how many teams communities may need. However, many communities have developed or are developing FACT teams. Dialogue about whom FACT should target is an important step toward developing its evidence base; thus, a definition of FACT eligibility—severe mental illness and three jail detentions in a calendar year—was proposed and modeled using administrative data from a large, urban community. For large, urban communities, the rule of thumb emerging from these data is that enough FACT teams would need to be developed to serve approximately 44% of their populations of persons with severe mental illness, or .05% of their adult populations.

As demonstrated by the results presented here, there are enough FACT-eligible consumers to warrant the creation of more specialty teams than many communities can develop, despite the relatively stringent eligibility criteria proposed here. One argument for developing specialty FACT teams is that staff may develop proficiency in working with the criminal justice system more quickly than ACT teams because of the frequency with which they must interact with the criminal justice system, unlike nonspecialty teams that encounter the criminal justice system less routinely. Moreover, it is important to note that in Lamberti and colleagues' ( 12 ) national study of FACT, 11 of the 16 (69%) FACT teams incorporated probation officers as team members; this is a clear departure from the traditional ACT model and provides further support for specialty teams.

However, many communities struggle to develop enough ACT capacity to meet the demand for ACT, so developing additional specialty teams will challenge public sectors to share information, resources, and expertise (that is, expertise related to the mental health and criminal justice systems). Access to evidence-based practices for persons with severe mental illness at the interface of the criminal justice and mental health sectors is extremely limited, and given the number of persons with severe mental illness involved with the criminal justice system who might need FACT, at least in the community where this study took place, the development of evidence-based practices for this group is paramount for local mental health and criminal justice authorities.

Several limitations to this study should be acknowledged. For example, the definition proposed here mirrors a contemporary and empirically valid definition of ACT eligibility and assumes that consumers who are incarcerated three or more times in a calendar year will benefit from the intensive services and aggressive outreach associated with ACT. The definition proposed here needs to be validated and requires empirical testing. Also, consumers returning from prisons and consumers who have fewer jail detentions but longer stays should be considered as the evidence base for FACT evolves and as our understanding of whom FACT should target evolves.

Further, the team estimates presented here are based upon a full-fidelity ACT model with a full-fidelity team of 100 consumers and a 1:10 staff-to-consumer ratio. However, it is not uncommon for ACT teams to stretch the staff-to-consumer ratio (for example, 1:12 or 1:15). Also, it is not clear whether the staff-to-consumer ratio for FACT should be similar to that of ACT or whether FACT staff members should have smaller caseloads given the complex needs of consumers involved with the criminal justice system. These factors would help to determine the number of teams a community may choose to develop.

The prevalence of mental disorders and the need for services are not one in the same ( 15 ). However, we were careful to use definitions of ACT and FACT eligibility that take priorities for care into account and would minimize the artificial inflation of those who need these services. Arguably, persons with severe mental illness who experience three or more psychiatric hospitalizations or jail detentions in a calendar year have profound needs. The FACT eligibility criteria proposed here are a reasonable starting place for identifying individuals who could benefit most from what will most likely be a scare resource.

These findings may not be generalizable to rural counties or counties with different jail detention patterns for persons with severe mental illness. The data used for this study are part of a larger study and are not available in the public domain. However, data sharing among mental health and criminal justice agencies is becoming increasingly common, and many community mental health centers are beginning to track criminal justice involvement. Thus a growing number of communities have the information needed to apply the proposed definition of FACT eligibility to identify the consumers who may benefit most from this service.

Conclusions

FACT teams have been developed to provide services for one of our nation's most vulnerable populations—persons with severe mental illness who are involved with the criminal justice system. There are a number of unknowns about FACT, and more research is needed to determine whether FACT can achieve desirable public health and public safety outcomes. Developing standardized eligibility criteria for FACT is an important first step toward developing its evidence base.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Mental Health Policy Research Network and by grant MH-63883 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors are grateful for the data management assistance of Chunyuan Liu, M.S., and Carol Porter, M.S.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Dixon L: Assertive community treatment: twenty-five years of gold. Psychiatric Services 51:759–765, 2000Google Scholar

2. Stein LL, Santos AB: Assertive Community Treatment of Persons With Severe Mental Illness. New York, Norton, 1998Google Scholar

3. Goldman HH, Gattozzi AA, Taube CA: Defining and counting the chronically mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 32:21–27, 1981Google Scholar

4. Clark RE, Teague GB, Ricketts SK, et al: Cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment versus standard case management for persons with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance abuse disorders. Health Services Research 33:1285–1297, 1998Google Scholar

5. Community Support Program: Guidelines. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1977Google Scholar

6. Bond GR, Witheridge TF, Dincin J, et al: Assertive community treatment for frequent users of psychiatric hospitals in a large city: a controlled study. American Journal of Community Psychology 18:865–891, 1990Google Scholar

7. Witheridge TF, Dincin J, Appleby L: Working with the most frequent recidivists: a total team approach to assertive resource management. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 5:9–11, 1982Google Scholar

8. Cuddeback GS, Morrissey JP, Meyer PS: How many assertive community treatment teams do we need? Psychiatric Services 57:1803–1806, 2006Google Scholar

9. Lamberti JS, Weisman R, Faden DI: Forensic assertive community treatment: preventing incarceration of adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:1285–1293, 2001Google Scholar

10. Calsyn RJ, Yonker RD, Lemming MR, et al: Impact of assertive community treatment and client characteristics on criminal justice outcomes in dual disorder homeless individuals. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health 15:236–248, 2005Google Scholar

11. Bond GR, Drake RE, Mueser KT, et al: Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental illness: critical ingredients and impact on patients. Disease Management and Health Outcomes 9:141–159, 2001Google Scholar

12. Lamberti JS, Weisman RL, Schwarzkopf SB, et al: The mentally ill in jails and prisons: towards an integrated model of prevention. Psychiatric Quarterly 72:63–77, 2001Google Scholar

13. McCoy ML, Roberts DL, Hanrahan P, et al: Jail linkage assertive community treatment services for individuals with mental illnesses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation 27:243–250, 2004Google Scholar

14. Mentally Ill Offender Crime Reduction Grant Program: Overview of Statewide Evaluation Findings. Sacramento, California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, March 2005. Available at www.bdcorr.ca.gov/cppd/miocrg/reports/miocrgreportpresentation.docGoogle Scholar

15. Mechanic D: Is the prevalence of mental disorders a good measure of the need for services? Health Affairs 22(5):8–20, 2003Google Scholar