Adequacy of Antidepressant Treatment in Spanish Primary Care: A Naturalistic Six-Month Follow-Up Study

Despite the high prevalence of major depression ( 1 , 2 ) and the availability of clinical guidelines for its treatment ( 3 , 4 ), major depression usually is inappropriately treated. This is especially the case when care is sought from primary care providers, who are the main health providers for these patients ( 1 , 5 , 6 , 7 ). A recent Spanish epidemiological study suggested that 23% of patients with major depression were adequately treated by their primary care physician ( 8 ). In clinical samples from primary care settings, rates of adequate antidepressant treatment ranged between 31% and 75% ( 5 , 6 , 9 , 10 ). Different findings among studies could be related to variations in the definition of adequacy. Previous studies have defined adequacy with only part of the relevant aspects of appropriateness, such as the kind of prescribed drug, minimum daily dosage, duration of treatment, or follow-up sessions with the prescribing practitioner. None of the studies has considered all four aspects. In addition, most investigations have addressed the appropriateness of treatment during only the acute phase of treatment with antidepressants (that is, during the first three months) and have included in the samples depressive disorders other than major depression. These other depressive disorders are problematic because they are not subject to standardized clinical guidelines ( 6 , 7 , 10 ).

Health care organization and availability of services may have an impact on treatment appropriateness. Because most of the current knowledge derives from studies considering private health care providers ( 1 , 5 , 6 , 9 , 10 ), we were interested in evaluating whether findings would vary when analyzing data from national health systems, where services are funded at the state level, with nearly universal health care access that is free of charge at the point of use and where primary care physicians play a key role as gatekeepers of care.

This study is part of a larger project for evaluating effectiveness of antidepressant treatment prescribed in primary care ( 11 ). The aim of this smaller study was to evaluate the adequacy of pharmacological antidepressant treatment prescribed by Spanish primary care physicians for treating major depressive episodes in real-world naturalistic conditions (usual care), during both the acute phase of antidepressant treatment and the first three months of the continuation phase. Because the continuation phase of antidepressant treatment was expected to be more stable, requiring less frequent monitoring, we decided to follow up with patients during the first three months of this phase.

Methods

Participants

The sample included 333 patients (18–75 years of age) from 16 primary care centers from the Barcelona area of Spain. All patients had received a diagnosis by the primary care physician of a depressive disorder and had started pharmacological antidepressant treatment. Exclusion criteria included being under pharmacological or psychotherapeutic antidepressant treatment for the previous two months, cognitive impairment severe enough to preclude an adequate interview, history of psychotic or bipolar disorder, and history of alcohol or drug abuse or dependence.

Measures

Primary care physicians diagnosed symptoms according to clinical criteria. Standardized diagnoses of current and past history of episodes of major depression were established with the major depression episode and the dysthymic disorder modules of the research version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) ( 12 ).

Depression severity was evaluated with the nine-item depression module of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) ( 13 ). The PHQ-9 is a self-report questionnaire designed to evaluate depressive symptoms during the prior two weeks. When used as a severity measure, possible scores range from 0 (absence of depressive symptoms) to 27 (severe depressive symptoms). It has been suggested that scores between 0 and 4 reveal minimal depressive symptoms, scores between 5 and 9 mild symptoms, scores between 10 and 14 moderate symptoms, scores between 15 and 19 moderately severe symptoms, and scores between 20 and 27 severe depressive symptoms ( 13 ). The PHQ-9 has demonstrated sensitivity to change across depressive status ( 14 ).

In addition, patients were asked for sociodemographic information, what kind of antidepressant they were taking and its dosage, treatment compliance, and number of primary care physician and psychiatric consultations in the past three months. Initial antidepressant prescription and dosage were informed by the prescribing primary care physician. Prescription at follow-up was informed by patients. Questions regarding treatment compliance were as follows: "Are you taking an antidepressant medication?" "When did you start to take the antidepressant?" "What is the name of the antidepressant you are currently taking?" "How many pills are you taking daily?" "How many milligrams does each pill have?" "Since the last interview, have you interrupted your treatment?" (if the patient responded yes, the follow-up question was "Why?") "Compared to what your primary care physician told you to do, are you taking the same number of pills?" (If the answer was no, the patient was asked how many he or she was taking.) "Are you taking these pills each day?" (If the answer was no, the patient was asked, "How frequently are you taking pills?")

Procedure

From December 2001 to December 2002, 63 primary care physicians recruited patients. Primary care physicians were instructed to ask all patients with a depressive disorder to whom they prescribed pharmacological antidepressant treatment for participation. In order to receive diagnoses according to standardized criteria, patients were then assessed by a fully trained clinical psychologist (who was independent of the clinical team) during a telephone interview performed within the week after antidepressant prescription. Validity of telephone administration of the SCID-I and PHQ-9 has been established elsewhere ( 15 , 16 ). Patients were reinterviewed after three and six months of beginning antidepressant treatment.

Primary care physicians prescribed antidepressants and dosages, performed patients' follow-ups, and evaluated the need for liaison consultations with mental health professionals on the basis of their own "usual care" criteria. During all follow-ups, they were blind to patients' SCID-I diagnosis. Patients were informed that other than for reasons of their safety (suicidal ideation), information gathered by telephone would not be disclosed to their primary care physicians. Information regarding only one patient was disclosed to the primary care physician and was not included in the analyses.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the participating institutions, and after a complete description of the study was provided to the participants, written informed consent was obtained.

Statistical analyses

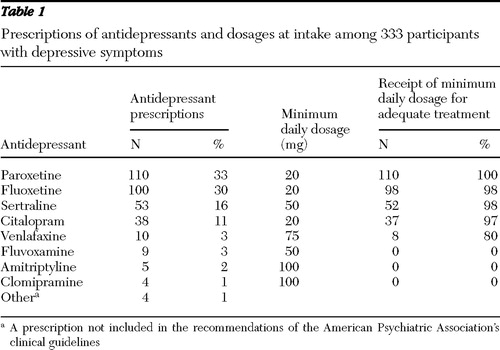

Adequacy of antidepressant treatment was determined with an algorithm of the criteria suggested by clinical guidelines. As recommended by the American Psychiatric Association ( 3 ) and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence ( 4 ), treatment adequacy was defined as a function of the usual minimum average daily dosage of a recommended antidepressant (summarized in Table 1 ), duration of the individual treatment, and a minimum of follow-up sessions with the prescribing physician. For the acute phase, treatment should last at least 12 weeks and include a minimum of three follow-up sessions. For the acute phase and the first three months of the continuation phase, antidepressant treatment should last a minimum of 24 weeks and include a total of four follow-up sessions (three during the acute phase and at least one during the first half of the continuation phase).

|

Clinical guidelines about pharmacological antidepressant treatment are provided for only major depression. However, many patients included in the study, according to the assessment with the SCID-I, had not been diagnosed as having had a major depressive episode. Therefore, two possible scenarios were considered when we analyzed treatment adequacy. First, we assumed that adequacy criteria for major depression may be applied to all patients with depressive disorders treated by primary care physicians (scenario 1); second, we analyzed the adequacy of treatment within the major depression group (according to SCID-I) (scenario 2).

Logistic regression models including a random-effect intercept at the primary care physician level were fitted to evaluate the factors associated with treatment adequacy (one set of models for the acute phase and another set of models for the acute phase and the following three months). Considering antidepressant treatment adequacy as the dependent variable, we included as independent variables gender, age (median centered), PHQ-9 results at intake (median centered), previous episodes of major depression, and presence or absence of additional psychiatric consultations. Because patients were treated by 63 primary care physicians who prescribed medication and provided follow-up according to their own criteria, the random-effect intercept at the primary care physician level allowed us to control for their variability. Analyses were conducted with Stata SE, version 8.0 ( 17 ).

Results

Of the 333 participants, 266 (80%) were women. The mean age of the sample was 45.51±14.49 years; 210 participants (63%) were married or living with a partner, 99 (30%) were homemakers, and 96 (29%) were on short-term disability. In the sample 76 participants (23%) had up to four years of formal education, 111 (33%) had five to eight years of formal education, 105 (32%) between nine and 12 years, and 41 (12%) had more than 12 years.

At intake, participants showed moderately severe depressive symptoms as assessed by the PHQ-9 scale (mean score of 14.8±5.2; possible scores range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms). Sixty patients (18%) had at least one previous episode of major depression, and the mean age at onset of the first episode was 38.1±12.2. After the administration of the SCID-I modules, 118 patients (35%) were diagnosed as having an episode of major depression (scoring 19.5±3.1 on the PHQ-9), 81 (24%) as having minor depression (scoring 13.7±2.3 on the PHQ-9), 15 (5%) dysthymic disorder (scoring 13.1±4.1 on the PHQ-9), and 119 (36%) depressive disorder other than major depression, minor depression, or dysthymic disorder (scoring 11.1± 4.7 on the PHQ-9).

Antidepressants prescribed at intake are summarized in Table 1 . In the sample 329 patients (99%) received one of the recommended antidepressants. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were the most prescribed, and compared with tricyclics, SSRIs were prescribed mostly at the recommended minimum usual daily dosage. Overall, 309 participants (93%) received a recommended antidepressant at a minimum usual daily dosage.

A total of 30 participants were lost to follow-up. Compared with participants completing the follow-up, these patients did not show significant differences in gender, age, and severity of symptoms and were not included in the analyses.

During the first three months (acute phase of treatment), 202 (67%) patients continued taking antidepressants prescribed by the primary care physician, and 122 (40%) received an adequate number of follow-up sessions. When considering the whole six-month period (acute phase and the first three months of the continuation phase), we found that 171 (56%) continued taking antidepressants as they were prescribed and 105 (35%) received an adequate number of follow-up sessions.

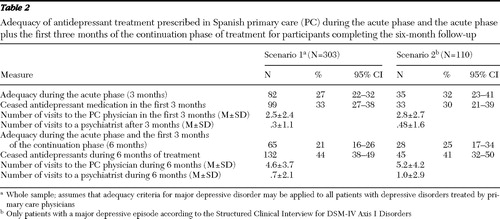

Table 2 summarizes the results regarding treatment adequacy during the acute phase and the first three months of the continuation phase of antidepressant treatment. When assuming that adequacy criteria for major depression may be applied to all patients with depressive disorders treated by the primary care physician (scenario 1), we found that 82 patients (27%) received adequate antidepressant treatment during the acute phase and 65 (21%) received adequate antidepressant treatment during the acute phase and the first three months of the continuation phase. When analyzing treatment adequacy within the major depression group (according to SCID-I) (scenario 2), we found that 35 (32%) received adequate treatment during the acute phase and 28 (25%) received adequate treatment during the acute phase and the first three months of the continuation phase.

|

Between 99 patients (scenario 1: 33%) and 33 patients (scenario 2: 30%) stopped taking antidepressant medication in the first three months of treatment, and between 132 patients (scenario 1: 44%) and 45 patients (scenario 2: 41%) stopped medication in the whole six-month period. Patients' main reason for ceasing their medication was they felt they had recovered sufficiently.

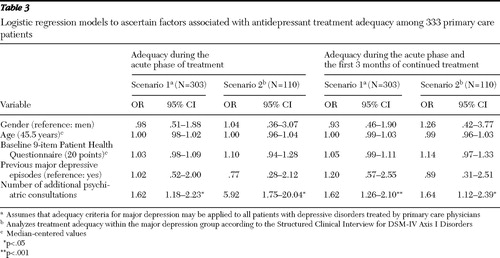

In general, the presence of additional psychiatric consultations was significantly related to an increased probability of receiving adequate treatment during both the acute phase and the first three months of the continuation phase for the two possible scenarios ( Table 3 ). Results were independent of gender, age, and presence of previous episodes of major depression.

|

Discussion

Treatment adequacy figures for the acute phase of treatment were between 27% and 32%. Figures for a longer period (acute phase plus the first three months of the continuation phase) were between 21% and 25%. Treatment adequacy at both time points was substantially lower than previously reported for primary care (on the basis of clinical records) but close to rates from a Spanish epidemiological study ( 8 ). Comparisons are difficult to make because of variations observed among adequacy criteria and diagnoses considered across studies. Previous research has included depressive disorders other than major depression in the assessment of treatment adequacy. This could affect results because adequacy in those studies was evaluated by considering criteria not specifically developed for the diagnoses considered. For example, assessment of treatment adequacy for minor depression was based on major depression clinical guidelines. As other authors have suggested ( 18 ), there are no treatment guidelines for minor depression, and the limited trial data do not offer definitive guidance on treatment options.

Spanish primary care providers prescribed mostly SSRIs. This preference also has been described recently for French primary care centers ( 19 ). Compared with tricyclics (all prescribed at subtherapeutic doses), SSRIs were mostly prescribed at the recommended minimum usual daily dosage.

Most patients did not receive an adequate number of follow-up contacts with the prescribing physician during the acute phase of antidepressant treatment. Several factors could explain this problem. Primary care physicians may vary in their interest and knowledge of psychiatric conditions. Also, in Spain, as occurs in most countries, primary care physicians work under extreme time pressure and experience burdensome workloads and burnout. Patients with depressive disorders could be viewed as adding to these demands ( 20 ).

An important issue affecting adequacy of treatment was patients' stopping their antidepressant medication, because it affected the duration of the individual treatment component of the algorithm constructed. These rates in our study were between 30% and 33% after three months and between 41% and 44% after six months, very close to findings in previous reports ( 21 ). Because ending antidepressant medication negatively affects the chance for a guideline-concordant treatment for depression, this should be considered seriously and must be addressed to ensure adequate treatment.

An aim of this study was to evaluate adequacy under real-world naturalistic conditions. Considering two scenarios allowed us to compare treatment adequacy between patients whom the primary care physicians believed to have depressive disorders requiring antidepressant treatment (a heterogeneous group) and patients more accurately diagnosed (with the SCID-I). In this study, Spanish primary care physicians prescribed antidepressants without making specific diagnoses. In fact, psychiatric diagnostic categories are rarely used routinely at this level. It has been suggested that primary care physicians usually make few treatment distinctions between major and less severe depression and that most cases are treated with antidepressants ( 22 ). In our study 65% of patients were treated presumably as if they had a major depressive episode. However, after a standardized diagnostic instrument (SCID-I) was administered, these patients were diagnosed as having other depressive disorders.

From a very restrictive position, we could argue that antidepressants prescribed to patients with depressive disorders other than major depression are inappropriate. Therefore, 65% of our sample would be inappropriately treated by the primary care physicians just for the fact of not having a major depression diagnosis, with the consequent associated expenditure (medication use and consultations). Antidepressants are not recommended for the initial treatment of mild depression because the risk-benefit ratio has been shown to be poor ( 4 ). For a significant number of people with mild depression, brief interventions delivered by the primary care team are effective (such as exercise or guided self-help) ( 4 ). Therefore, before treating depressive disorders other than major depression or mild forms of depression, primary care physicians could assume a "watchful waiting" position, consider a further assessment, and then decide how to proceed.

If clinical guidelines are available only for major depression, an effort should be made to increase recognition of depressive symptoms and accuracy of diagnosis in primary care (for example, improving education of primary care physicians regarding mental disorders) and to develop clinical guidelines for treating patients seeking primary care for depressive disorders, such as minor depression, dysthymic disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, or subthreshold major depression. The need for better recognition and diagnosis is quite relevant considering, for example, that there is evidence that minor depression increases the odds of having an onset of a major depressive episode ( 23 ) and that subthreshold depression could predict it ( 24 ).

In this study, primary care physicians for the most part prescribed suggested antidepressants (99%) at adequate dosages. However, one major problem was that they did not perform the recommended number of follow-up sessions during the acute phase of treatment.

Psychiatric consultations were significantly related to treatment adequacy. This association was significant even after adjusting for depression severity (PHQ-9). Previous studies suggest that collaborative interventions between primary care providers and psychiatrists could promote higher adequacy rates and adherence to antidepressant medication at guideline dosage levels (5,25). Thus it seems that coordination between primary care and psychiatric providers could increase antidepressant treatment adequacy at the primary care level. However, it is important to remember that psychiatric consultations were prescribed by primary care physicians according to their "usual care" criteria. That is, consultations were not randomly assigned. Thus it could represent a selection bias affecting results.

Some limitations should be acknowledged. First, adequacy was evaluated by considering a major depression diagnosis that was not disclosed to primary care physicians. That is, we judged treatment adequacy for major depression without considering that primary care physicians rarely use this psychiatric category. This fact motivated the use of two possible scenarios that allowed more or less conservative evaluations of adequacy. Second, treatment compliance was assessed by means of patients' self-report. Thus results should be interpreted with caution, including consideration that patients' reports could have biased results. Third, despite available international clinical guidelines, the Spanish health system has not developed local clinical guidelines for the treatment of depression. This deficit could affect availability of evidence-based knowledge about major depression at a primary care level. Fourth, we did not consider whether primary care physicians took into account patients' preferences for medication. From the latest perspective of clinical guidelines issued by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence ( 4 ), such information should be taken into account in evaluations of treatment adequacy. Thus we do not know to what extent including such information would change these results. Finally, we followed up on patients during a six-month period, covering the acute phase of treatment and the first three months of the continuation phase. Future studies could perform longer follow-ups in order to evaluate antidepressant treatment adequacy during acute, continuation, and maintenance phases.

Conclusions

In Spanish primary care (where health services are publicly financed), treatment adequacy seems poor during both the acute phase and the first three months of the continuation phase of antidepressant treatment. Efforts should be made to discover why adequacy is low despite available clinical guidelines and to favor collaborative interventions with the mental health sector that may improve the adequacy of treatment.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by grant 063-26-2000 from the Catalan Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Research and by grant RD06-0018-0017 from the Spanish Ministry of Health, Health Institute Carlos III. The study is part FIS-G03/202 of the IRYSS (Red de investigación cooperativa para la Investigación en Resultados de Salud y Servicios Sanitarios) Network.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 289:3095–3105, 2003Google Scholar

2. Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al: Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 420:21–27, 2004Google Scholar

3. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder, 2nd ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

4. National Institute for Clinical Excellence: Depression: Management of Depression in Primary and Secondary Care. Available at www.nice.org.uk/cg023niceguidelineGoogle Scholar

5. Weilburg JB, O'Leary KM, Meigs JB, et al: Evaluation of the adequacy of outpatient antidepressant treatment. Psychiatric Services 54:1233–1239, 2003Google Scholar

6. Kniesner TJ, Powers RH, Croghan TW: Provider type and depression treatment adequacy. Health Policy 72:321–332, 2005Google Scholar

7. Balestrieri M, Carta MG, Leonetti S, et al: Recognition of depression and appropriateness of antidepressant treatment in Italian primary care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 9:171–176, 2004Google Scholar

8. Fernández A, Haro JM, Codony M, et al: Treatment adequacy of anxiety and depressive disorders: primary versus specialised care in Spain. Journal of Affective Disorders 96:9–20, 2006Google Scholar

9. Charbonneau A, Rosen AK, Ash AS, et al: Measuring the quality of depression care in a large integrated health system. Medical Care 41:669–680, 2003Google Scholar

10. Joo JH, Solano FX, Mulsant BH, et al: Predictors of adequacy of depression management in the primary care setting. Psychiatric Services 56:1524–1528, 2005Google Scholar

11. Serrano-Blanco A, Pinto-Meza A, Peñarrubia MT, et al: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: are there differences in effectiveness in primary care? Primary Care and Community Psychiatry 11:113–120, 2006Google Scholar

12. First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al: User's Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, research version. New York, Biometrics Research, 1996Google Scholar

13. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB: The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine 16:606–613, 2003Google Scholar

14. Löwe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, et al: Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Journal of Affective Disorders 81:61–66, 2004Google Scholar

15. Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, Rutherford MJ, et al: Comparability of telephone and in-person Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) Diagnoses. Assessment 6:235–242, 1999Google Scholar

16. Pinto-Meza A, Serrano-Blanco A, Peñarrubia MT, et al: Assessing depression in primary care with the PHQ-9: can it be carried out over the telephone? Journal of General Internal Medicine 20:738–742, 2005Google Scholar

17. Stata, version 8.0. College Station, Tex, Stata Corp, 2003Google Scholar

18. Ackerman RT, Williams JW: Rational treatment choices for non-major depressions in primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 17:293–301, 2002Google Scholar

19. Rambelomanana S, Depont F, Forest K, et al: Antidepressants: general practitioners' opinions and clinical practice. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 113:460–467, 2006Google Scholar

20. Mechanic D: Barriers to help-seeking, detection, and adequate treatment for anxiety and mood disorders: implications for health care policy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 68(suppl 2):20–26, 2007Google Scholar

21. Demyttenaere K, Enzlin P, Dewé W, et al: Compliance with antidepressant in primary care setting: 1. beyond lack of efficacy and adverse events. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62(suppl 22):30–33, 2001Google Scholar

22. Williams JW Jr, Rost K, Dietrich AJ, et al: Primary care physicians' approach to depressive disorders: effects of physician specialty and practice structure. Archives of Family Medicine 8:58–67, 1999Google Scholar

23. Fogel J, Eaton WW, Ford DE: Minor depression as a predictor of the first onset of major depressive disorder over a 15-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 113:36–43, 2006Google Scholar

24. Cuijpers P, Smit F, Willemse G: Predicting the onset of major depression in subjects with subthreshold depression in primary care: a prospective study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 111:133–138, 2005Google Scholar

25. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al: Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA 273:1026–1031, 1995Google Scholar