A National Survey of State Licensing, Regulating, and Monitoring of Residential Facilities for Children With Mental Illness

Residential facilities for children and adolescents with mental illness have been surrounded by controversy in recent years, as media reports have focused on abuses in such facilities ( 1 , 2 , 3 ) and more states have shifted resources from residential care to community services ( 4 , 5 , 6 ). State and federal policy makers also are concerned about the costs of residential care for children ( 7 , 8 ). According to the 1999 report on mental health by the Surgeon General ( 9 ), "although used by a relatively small percentage (8 percent) of treated children, nearly one-fourth of the national outlay on child mental health is spent on care in these settings."

Residential settings for children include psychiatric residential treatment facilities, residential treatment centers, residential treatment programs, therapeutic group homes, and therapeutic foster care residences. These facilities are owned by a wide variety of public and private entities and are operated under the jurisdiction of various state agencies, including departments of child welfare, juvenile justice, and mental health ( 10 ). Most children and adolescents who enter residential settings are sent by child welfare agencies, detention centers, and juvenile courts ( 11 ).

Researchers, clinicians, and state officials generally agree that the number of facilities and the number of children living in residential settings have increased during the past two decades, apparently in response to the closure of long-term psychiatric hospitals and shorter stays in inpatient institutions ( 12 ). In 2000 a total of 474 residential treatment centers for emotionally disturbed children were reportedly operated under the auspices of state mental health organizations, compared with 261 centers in 1970; the number of beds in these centers more than doubled during this 30-year period, increasing from 15,129 to 33,421 ( 13 ). However, the total number of residential beds is likely to be substantially higher if settings operated by other departments are included in addition to those operated by mental health agencies. One source estimates that as of 1997 a total of 66,000 children and adolescents were living in residential treatment programs or centers designated as mental health organizations ( 10 , 14 ), although this number does not include children living in many facilities operated by child welfare or juvenile justice agencies.

Media reports have highlighted serious abuses in certain types of residential facilities—variously known as therapeutic boarding schools, emotional growth schools, or behavior modification programs—that have proliferated in the past 15 years ( 15 ). Although most of these facilities are unlicensed and unregulated, some reports indicate that such concerns also extend to facilities that are licensed and regulated by states ( 1 , 2 , 3 ). These concerns point to the need for greater scrutiny of how states regulate the entire spectrum of residential facilities.

Although states have primary responsibility for regulating residential facilities for children with mental illness to ensure that they meet basic safety, staffing, and service delivery standards, states vary widely in specific regulatory practices. A few reports have addressed policy questions related to monitoring residential facilities in selected states ( 7 , 16 , 17 ), but little national information is available to help policy makers understand the many policies and procedures used by states to regulate residential facilities for children with mental illness.

This article describes the findings of a recent survey of state officials that examined the methods used by states to license, regulate, and monitor such residential facilities. The study focused on residential facilities that provide services primarily to children with serious emotional or behavioral disorders and that provide 24-hour staffing and at least some therapeutic services beyond housing. The survey was conducted by Mathematica Policy Research in 2003–2004 and was sponsored by the Center for Mental Health Services of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The findings presented here are drawn from the full report of the survey, State Regulation of Residential Facilities for Children With Mental Illness ( 18 ); a companion report provides parallel information about residential treatment facilities for adults ( 19 ). Both reports are available from SAMHSA's National Mental Health Information Center and may also be accessed online (www.samhsa.hhs.gov).

Methods

Criteria for including facilities

After a review of descriptions of state mental health systems found on states' Web sites, the criteria for identifying facilities to be included in the national survey were developed with guidance from the project's advisory committee. This group included experts in mental health and housing who represented a range of state and federal agencies, provider and advocacy organizations, and researchers. The study criteria were designed to be broad enough to capture the wide range of state-regulated residential facilities that serve children, including facilities regulated by any state agency, such as mental health departments, departments of children and families, departments of health, and other agencies; offer varied sets of residential services; and focus on diverse subgroups of children and adolescents with mental illness, including children with extreme behavior problems or children with multiple problems.

To be included in this study, facilities had to specialize in the treatment of children with serious emotional or behavioral disorders, including children who had a dual diagnosis (mental illness and substance abuse or mental illness and developmental disability) as long as mental illness was the primary problem; to furnish (in single or several facilities) food, shelter, and some treatment or services to three or more persons unrelated to the proprietor; to provide staffing 24 hours per day, seven days per week; and to operate under some state authority, such as a state office granting pertinent licenses or a state mental health authority. In addition facilities had to include at least 50% of residents whose need for placement was based on mental illness; include children with average stays of 30 days or longer; and provide at least some on-site therapeutic services beyond housing (such as group therapy, individual therapy, and medication management) either by staff or under contract.

Given the diverse array of residential settings that serve children with mental illness and the complex nature of the data collection process, it was necessary to limit the focus of the study to certain types of facilities. The study criteria were thus designed to exclude facilities for children who were homeless or who had physical rather than mental or emotional disabilities; psychiatric hospitals or inpatient facilities of general hospitals; nursing homes; facilities where children stay for short periods, such as detention centers and community shelters; residential substance abuse treatment programs, unless the program was specifically for children with a dual diagnosis of both a mental disorder and a substance use disorder; and individual foster care homes.

As others have noted, the lack of standard definitions of key terms such as "psychiatric residential facility," "residential treatment center," and "group home" has impeded efforts to develop a national statistical portrait of residential settings for both adults and children with mental illness ( 20 ). States have adopted widely discrepant terms for essentially similar institutional entities, and conversely, states operate facilities that provide markedly different sets of services and living environments yet have similar names. For this reason, facilities were included in the study based on the criteria listed above rather than on category names.

Survey design and implementation

An Internet search of relevant Web sites conducted for ten states of varying sizes in different geographic regions made it clear that states rely on different regulatory practices for different types of licensed facilities. For example, a state may license facilities that house a large number of children (more than 16) under a different set of procedures than facilities that house a smaller number of children. Accordingly, the survey was designed to allow state officials to respond separately for each type of facility in their particular state.

On the basis of information gathered from the Internet search, survey items were organized into five topic areas: program characteristics (number of residents, beds, average length of stay, and staffing ratios); licensing, certification, and accreditation (including a chart to determine which state agencies provided licensing, certification, and accreditation for each program type); program services (questions about whether the facilities were obligated to provide specific services); program monitoring and oversight (including questions about which state agency conducted site visits and responded to critical incidents); and financing (questions about funding sources and per diem rates). The final questionnaire consisted of approximately 50 questions and required slightly more than one hour to complete.

The questionnaire was reviewed by several of the members of the project's expert advisory group and revised according to their feedback. Pilot testing of the questionnaire was then conducted in three states, and minor modifications were made to ensure that the questions were as concise as possible. Internet searches were conducted for all 50 states to identify a preliminary list of facility types that met the study's criteria and state officials who potentially could serve as primary contacts—for example, the director of child services in the mental health department. Contact persons were selected on the basis of positive responses to questions asking whether they were knowledgeable about the state's regulatory procedures or whether they would be able to gather the relevant information from other staff. Approximately four hours of staff time per state were needed to identify an appropriate contact person and establish an appropriate list of facility types. The contact person was then sent one or more questionnaires, depending on the number of facility types in the state. The name of each facility type was embedded in the questionnaire to ensure that respondents knew to which facility type the questions applied.

Several individuals typically were involved in responding to the questionnaire, because in most states no one person was familiar with all of the topics covered. Substantial efforts were made to ensure that the respondents completed a survey for all types of residential facilities that met the study's definition, but in some instances respondents may not have been aware of all types of such facilities, and thus no information is available for those types.

A total of 89 questionnaires were sent out to 42 of the 51 states (including the District of Columbia); 38 states completed at least one usable questionnaire. Of the remaining 13 states nine did not respond to requests to participate in the survey (repeated calls or e-mails to the contact person went unanswered or no primary contact could be located) or state officials indicated that rules were under revision; one state indicated that it did not have the resources to respond to the questionnaire but provided a brief explanation of the housing options for children with mental illness; and three states had programs that did not fit the study's criteria (for example, the state used only foster homes, out-of-state placements, or hospitals).

Of the 89 questionnaires sent out, 76 were returned by the end of the study period. Of the 76 questionnaires received, five were excluded because of missing responses for almost all of the questions or because closer inspection revealed that the facility type did not fit the study criteria.

Extensive efforts were made to check questionable data, and states approved the final data used for the analyses. Therefore, this report reflects the most accurate national data available on the characteristics of the facilities that met the study's criteria and on the methods that states used to regulate residential facilities for children with mental illness.

Results

Characteristics of facilities providing residential care

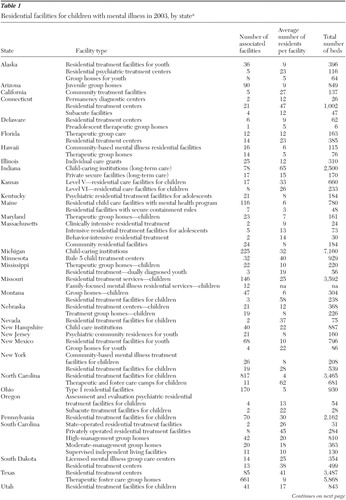

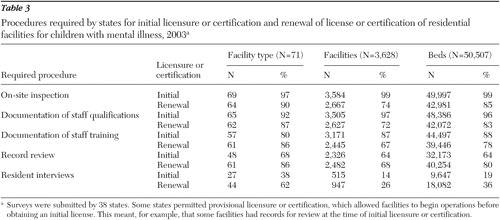

The survey yielded information on 71 types of residential facilities in 38 states. As shown in Table 1(Table 1 continued) , there was considerable variation in the number of facilities associated with each facility type, in the average number of residents in a single facility within each type, and in the total number of beds in all facilities within a facility type. Overall, the 71 facility types in the survey accounted for 3,628 separate residential facilities, and these facilities included 50,507 beds as of September 30, 2003. Twenty-three of the 71 facility types (32% of all types) had eight or fewer associated facilities, and seven facility types (11% of types) had more than 100 associated facilities.

|

|

About one-third of the 71 facility types (23 types) had fewer than ten children on average in each facility; these 23 facility types accounted for 65 percent of all facilities and 31 percent of all beds. Eleven percent of all facility types (eight types) had 40 or more residents on average, accounting for 7% of associated facilities and 21% of beds.

Length of stay

Data on length of stay were unavailable for more than one-fifth of the 71 facility types, accounting for 39 percent of all facilities and almost half (46%) of all beds. In 18 facility types (accounting for about 10% of facilities and 10% of beds), average stays ranged between one and six months. In about one-third of all facility types (accounting for about one-third of facilities and beds), stays ranged between seven and 12 months. In less than 20% of facility types (accounting for 13% of facilities and 8% of beds), children stayed for longer than a year on average (data not shown). Maximum lengths of stay were mandated for facilities in only ten of the 71 facility types (14% of facility types, accounting for 11% of all facilities).

Secured units

Twenty-six types of facilities (37% of facility types) were allowed by state law to maintain secured or locked units. However, in half of the facility types allowed to have secured units, 50% or less of the facilities actually maintained such units. Locked units were much more common in larger facilities: whereas slightly more than 80% of facilities that averaged more than 16 residents were allowed to have locked units, less than 10% of facilities that averaged between three and 16 residents were allowed to have them.

States' regulatory methods

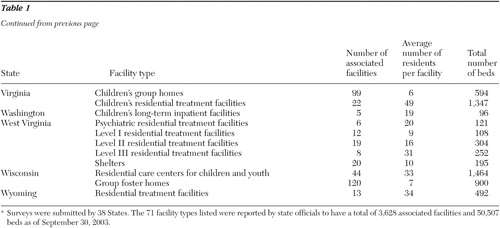

Licensure and certification. As shown in Table 2 , state departments of children and families licensed or certified 30 of the 71 facility types (42%), accounting for 19% of all facilities and 27% of all beds. Departments of health and state mental health agencies also played a major role, each certifying about one-third of the facility types in the study. Departments of health and human services were involved with facility types that had a large number of facilities. Similarly, seven facility types were licensed or regulated by other departments and agencies, such as Medicaid agencies or departments of protective services, but these seven types accounted for 35% of all beds, meaning that these departments were involved with facility types that served large numbers of residents. Thirty of the 71 facility types (42%) had to respond to two licensing agencies or departments, and three facility types had to respond to three or more licensing agencies (data not shown).

|

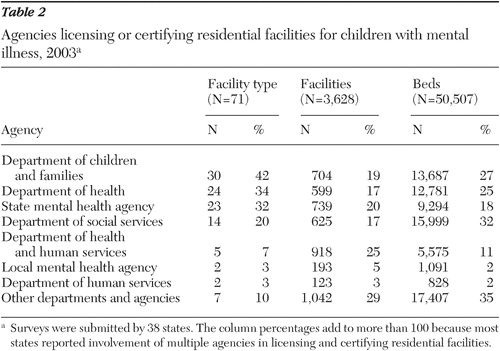

Table 3 shows that virtually all facility types (97%) had to have an on-site inspection for initial licensure or certification, and almost all (90%) had to have such an inspection for licensure renewal. Most facility types had to submit documentation of staff qualifications for initial licensure and certification (91% of facility types) as well as for licensure renewal (87%).

|

Documentation of staff training was required for 80% of facility types at the time of initial licensure and for 86% at the time of licensure renewal. Record reviews had to occur at the time of initial licensure for 68% of facility types and at the time of licensure renewal for 86% of facility types. Only 38% of facility types (accounting for 14% of all facilities) were required to conduct interviews with residents at initial licensure, and 62% (26% of all facilities) at licensure renewal.

In 2003 respondents in seven states indicated that licenses or certifications were revoked for 26 residential facilities for children with mental illness, or less than 1% of all facilities.

Complaint reviews. Just as several agencies were frequently involved in providing licensure and certification for residential facilities for children with mental illness, several agencies reviewed complaints filed against these facilities. State departments of children and families reviewed complaints for 36 of the 71 facility types, accounting for 27% of the facilities and 31% of the beds (data not shown). State mental health agencies reviewed complaints for 47% of facility types, which accounted for 29% of facilities and 35% of beds. In comparison, departments of health reviewed fewer facility types (21%), but such facilities accounted for 36% of facilities and 30% of beds.

Twenty of the facility types (28%, accounting for 40% of facilities and 47% of beds) were also subject to review by other entities, such as the Medicaid agency, department of justice, office of child care services, state commission on quality of care, behavioral health managed care organizations, and protection and advocacy offices.

Critical incident reporting. More than 90% of the facility types were required to report deaths, suicides, and incidents or allegations of abuse or neglect. Suicide attempts had to be reported by 78% of facility types (about two-thirds of all facilities), and 63% of facility types (about 40% of all facilities) had to report hospitalizations of residents. Other critical incidents that facilities were required to report included fires, medication errors, serious injuries, runaways, and sexual incidents (data not shown).

Announced and unannounced visits. States made announced visits to at least some of the associated facilities in 65 of the 71 facility types (92% of types) in the study. The proportion of facilities within a facility type that were visited, however, varied from 100% to 1%. Unannounced visits were made to at least some of the facilities in 46 of the 71 facility types (65% of facility types); the proportion of facilities receiving unannounced visits varied from 100% to 5%. Visits were made by the same array of state departments and agencies that were responsible for reviewing complaints.

Regulations governing selected facility characteristics. More than three-quarters (78%) of all facility types and 61% of all facilities were subject to required resident-to-staff ratios. Of the 55 facility types required to have a particular daytime resident-to-staff ratio, the required minimum ratio was between two and four residents per staff member for 15 facility types (27%); five and eight residents per staff member for 26 facility types (47%); and nine and 20 residents per staff member for ten facility types (18%). Facilities with three to 16 residents were subject to state laws imposing lower ratios (that is, fewer residents per staff member) than facilities averaging 17 or more residents. For most facility types, nighttime ratios were slightly higher (that is, a single staff member was responsible for more residents) than daytime ratios (data not shown).

Approximately two-thirds (68%) of facility types and more than 80% of facilities were subject to a minimum education requirement for facility directors; however, smaller facilities were less likely to be subject to this requirement than were larger facilities. For 30% of facilities with such a requirement, less than a bachelor's degree was required; for 22% of such facilities, a bachelor's degree was required; for 32% a master's degree was required; for 12% a combination of education and relevant experience was required; and for 3% relevant experience was required.

Slightly more than 6% of the facilities included in the survey were required to obtain certification from at least one accrediting organization, such as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, the Council on Accreditation for Children and Family Services, and the National Committee for Quality Assurance.

Services and sources of financing

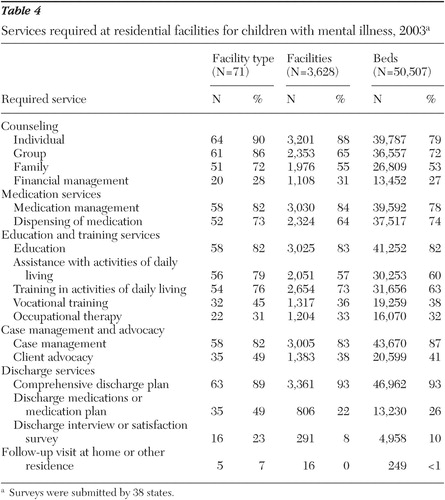

Required services. As Table 4 shows, 90% of all facility types (accounting for 88% of facilities) were required by state law to provide individual counseling. Eighty-six percent of facility types were required to provide group counseling, 72% were required to provide family counseling, 82% were required to provide medication management, and 73% were required to dispense medications. Approximately half of facility types (49%) were required to provide client advocacy (that is, working with other agencies on behalf of the individual), whereas 82% were required to provide case management. A majority of facility types (89%) were required to provide residents with a comprehensive discharge plan, and 49% of facility types were required to provide discharge medications or a medication plan. Seven percent of facility types were required to provide follow-up home visits, and 23% were required to conduct discharge interviews or client satisfaction surveys.

|

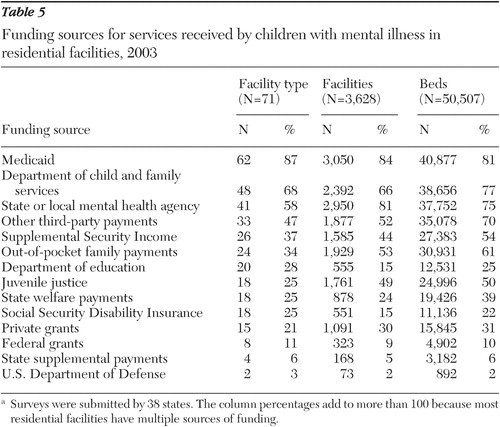

Sources of financing.Table 5 shows that most facilities relied on several sources of funding. The three most important funding sources were state Medicaid programs, state departments of child and family services, and state and local mental health agencies. Between 34% and 47% of facility types received funding from other third-party payments, Supplemental Security Income payments, and family out-of-pocket payments. Approximately one-fifth to one-quarter of facility types received funding from departments of education, juvenile justice authorities, state welfare departments, Social Security Disability Insurance payments, and private grants.

|

Discussion

Findings from this study highlight the substantial variation across states in the methods used in 2004 to regulate residential facilities for children with mental illness. States relied on at least several regulatory methods, but no state used all of the possible methods, which included requirements for announced and unannounced visits, mandated staff-to-client ratios, minimum levels of education for facility directors, specifications for critical-incident reporting, specific licensing practices, mandated complaint-review procedures, and accreditation from designated state or national organizations.

The types of facilities regulated by states differed on parameters such as mission, administrative structure, and funding sources. States referred to facilities by different names, making it difficult to identify the extent to which facilities across various states were similar.

Study findings demonstrate that organizations operating facilities for children with mental illness faced a complex regulatory environment in 2004. A wide variety of state agencies with different missions and functions oversaw these residential facilities; furthermore, in most states, several agencies were involved in licensing, regulating, and reviewing complaints against residential facilities. Facilities also may have had administrative reporting requirements from their multiple funding sources.

Several factors limit the generalizability of the study's results. First, although 80% of states responded to the questionnaire (the 38 states that completed the questionnaire plus the three that indicated that they did not license facilities meeting study criteria), results may not be representative of all states.

Second, responses were obtained from state staff who were willing to complete a structured questionnaire, and our results depend on the extent and accuracy of the information available to the survey respondents. These respondents varied in terms of their familiarity with the areas covered in the questionnaire and in how many colleagues they asked to help in developing the responses. Some states lacked ready access to important data about residential facilities for children with mental illness; for example, respondents were unable to provide information on average length of stay for 21% of facility types, accounting for 39% of facilities and 46% of beds. Because we made extensive efforts to check questionable data through telephone calls and e-mails to state officials and because officials in each state approved the final data used for the analyses, this report reflects the most accurate national information available regarding the characteristics of facilities that met the study criteria and the methods used by states to regulate such facilities in 2003. Nonetheless, our results should be interpreted cautiously because of limitations in some respondents' capacity to answer survey questions. Finally, the survey asked about regulations and requirements, but additional research is needed to determine the extent to which states are actually using the regulatory methods available to them.

Conclusions

Leaders in the children's mental health field recently noted that "residential programs serving children with special mental health challenges should be properly licensed and monitored by state government, and accredited by independent accrediting organizations" ( 21 ). Moreover, a bill introduced in Congress in 2005 would authorize grants to states to support inspections of child residential treatment facilities. If enacted, the bill would mandate grants to "hire and train individuals … to carry out periodic, unannounced inspections of child residential treatment facilities" and "collect and maintain data from the inspections."

To ensure that the residential care component of the service system effectively addresses the needs of children with mental illness and their families, states need better data on methods for regulating residential facilities. State officials are obligated both to ensure that children in these facilities receive effective services and to prevent the occurrence of critical incidents that could jeopardize their well-being. Such residential facilities are costly, and mental health budgets in most states are limited. Policy makers need good information on methods for regulating residential facilities to ensure that public dollars are spent effectively.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The study was conducted by Mathematica Policy Research through contract 282-98-0021 with the Center for Mental Health Services of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Special Reports: Throwaway kids. New York JournalNews, June 2002. Available at www.nyjournalnews.com/rtc/index1.htmGoogle Scholar

2. Chan, S, Higham S: District reexamines out-of-town centers: city focusing on treating youths locally. Washington Post, July 16, 2003, p A13Google Scholar

3. Chan S, Higham S: Poor care, abuses alleged at Riverside: profit was paramount, former workers say. Washington Post, July 15, 2003, p A1Google Scholar

4. Burns BJ: Reasons for hope for children and adolescents: a perspective and overview, in Community Treatment for Youth: Evidence-Based Interventions for Severe Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. Edited by Burns B, Hoagwood K. New York, Oxford University Press, 2002Google Scholar

5. Summary of Effective Interventions for Youth With Behavioral and Emotional Needs. 2004 Biennial Report From the Evidence Based Service Committee, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division. Honolulu, Hawaii Department of Health, 2004. Available at http://www.hawaii.gov/health/mental-healthGoogle Scholar

6. Sheidow A, Bradford W, Henggeler MR, et al: Treatment costs for youths receiving multisystemic therapy or hospitalization after a psychiatric crisis. Psychiatric Services 55:548–554, 2004Google Scholar

7. Residential Treatment Center Rate Setting and Monitoring. Denver, Colorado Office of the State Auditor, Jan 2002Google Scholar

8. Ireys HT, Pires S, Lee M: Public Financing of Home and Community Services for Children and Youth With Serious Emotional Disturbances: Selected State Strategies. Washington, DC, Mathematica Policy Research, May 2006Google Scholar

9. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 1999Google Scholar

10. Pottick K, Warner L, Isaacs M, et al: Children and adolescents admitted to specialty mental health care programs in the United States, 1986 and 1997, in Mental Health, United States, 2002. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ. DHHS pub no SMA-3938. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004Google Scholar

11. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-0382. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

12. Manderscheid R, Atay J, Hernandez-Cartagena M, et al: Highlights of organized mental health services in 1998 and major national and state trends, in Mental Health, United States, 2000. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ. DHHS pub no SMA-01-3537. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2001Google Scholar

13. Manderscheid R, Atay J, Male A, et al: Highlights of organized mental health services in 2000 and major national and state trends, in Mental Health, United States, 2002. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ. DHHS pub no SMA-3938. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004Google Scholar

14. Milazzo-Sayre L, Henderson ML, Manderscheid R, et al: Persons treated in specialty mental health care programs, United States, 1997, in Mental Health, United States, 2000. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ. DHHS pub no SMA-01-3537. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2001Google Scholar

15. Fact Sheet: Children in Residential Treatment Centers. Washington, DC, Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law. Available at www.bazelon.org/issues/children/factsheets/rtcs.htmGoogle Scholar

16. Maryland Task Force to Study the Licensing and Monitoring of Community-Based Homes for Children: Final Report to the Governor. Baltimore, Governor's Office for Children, Youth, and Families, Sept 2002Google Scholar

17. State Oversight of Residential Facilities for Children. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General, May 2000Google Scholar

18. Ireys H, Achman L, Takyi A: State Regulation of Residential Facilities for Children With Mental Illness. DHHS pub no SMA-06-4167. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006Google Scholar

19. Ireys H, Achman L, Takyi A: State Regulation of Residential Facilities for Adults With Mental Illness. DHHS pub no SMA-06-4166. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006Google Scholar

20. Fleishman M: The problem: how many patients live in residential care facilities? Psychiatric Services 55:620–622, 2004Google Scholar

21. A START (Alliance for the Safe, Therapeutic, and Appropriate Use of Residential Treatment). University of South Florida and Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law. Available at http://astart.fmhi.usf.eduGoogle Scholar