Social Networks and Their Relationship to Mental Health Service Use and Expenditures Among Medicaid Beneficiaries

A social network embodies both the quantity and quality of relationships that an individual has with others. The relationship between social networks and mental health service utilization has been mixed ( 1 , 2 ). Some studies have reported a positive relationship between social networks and mental health service utilization, whereas others have reported a negative relationship. Few studies have investigated the relationship between social networks and expenditures and between social networks composed of friends and those composed of family members. The study presented here is an exploratory study that examined the social networks of consumers with severe mental illness and the relationships of these networks to different types of mental health service utilization and their associated service expenditures.

Social networks are measured by specific network properties that emphasize both structure and function. Structural measures are properties of relationships that are easily quantifiable, such as the number of social ties and the frequency of contact with other persons. Functional measures emphasize the qualitative nature or type of relationship and perceptions of supportiveness ( 3 , 4 ). In this study the concept "social network" signifies only the structural measures of social networks, such as the number and frequency of contacts with family or friends.

Social networks may influence service utilization in either positive or negative directions. Gourash ( 5 ) outlined four hypothetical avenues through which social networks influence mental health service utilization: buffering the experience of stress, serving as substitutes for mental health providers, advocating for or referring to services, or transmitting attitudes, values, and norms regarding mental health services. By buffering the experience of stress or serving as substitutes for mental health providers, social networks may reduce service utilization. Social networks may also increase mental health service utilization through advocacy and referral. Finally, social networks may influence service utilization by transmitting attitudes, values, and norms regarding mental health services, which would result in either an increase or a decrease in service utilization, depending on the nature of those values. Individuals with larger social networks may use fewer services and have lower expenditures for different types of mental health services because their social networks may buffer the experience of stress, or similarly, individuals may use their social networks as a substitute for mental health services. On the other hand, people with larger social networks may use more mental health services because their family and friends may encourage them to seek care when they need it and may also provide the means to access services—for example, referrals to providers, transportation, and financial resources for care.

Increasing the size of a person's social network influences the amount of social support and aid received ( 5 , 6 ). In general, people who have larger social networks tend to fare better than people who have smaller social networks ( 2 ). Individuals with severe mental illness tend to have smaller social networks. In their synthesis of the social network literature, Albert and colleagues ( 2 ) found that the average reported social network size in the general population was about 25 people, whereas the average social network size among individuals with severe mental illness ranged from 4.5 to 13 people.

Individuals with severe mental illness have social networks that are qualitatively different from those of individuals without mental illness. In addition to the aforementioned differences in social network size, the social networks of individuals with severe mental illness are more likely to include relatives, other mental health users, and mental health professionals ( 1 , 2 , 7 , 8 ). Positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia have been associated with qualities of social networks. Among individuals with schizophrenia, more severe and negative symptoms are related to smaller social network size ( 9 , 10 ). Furthermore, a study of the relatives of individuals with schizophrenia found that the social networks of relatives with chronic mental illness were smaller and perceived to be less supportive than those of relatives of individuals with chronic physical conditions ( 11 ).

Studies of social networks and mental health service utilization have reported mixed results ( 1 ). This study sought to clarify the association between social networks among Medicaid clients with severe mental illness and their utilization of mental health services. This study differs from previous studies because it investigated the probability of use of three different types of mental health services—inpatient services in local hospitals, inpatient services in state hospitals, and outpatient services—and investigated differences between social networks composed of friends and those composed of family members.

Methods

Background

In an effort to contain the costs of mental health services, the state of Colorado implemented a prepaid, capitated payment system in 1995 for its Medicaid mental health consumers. The natural experiment design for the study of capitation in Colorado is described in detail elsewhere. The study presented here took advantage of the longitudinal, prospective survey design with a randomly selected sample stratified on gender and diagnosis ( 12 , 13 ). The administrative and survey data used in this study were from the larger research project. The evaluation project was conducted to examine utilization and cost of services, as well as outcomes before and after the implementation of a capitated payment system for Colorado's Medicaid mental health services. Persons living in capitated areas were compared with those in areas that remained on a fee-for-service system.

Data sources and sample

Psychosocial and demographic characteristics, mental health outcomes, and social networks data were collected from in-person interviews conducted at six-month intervals between 1994 and 1997. In the study presented here, only three of the five survey data points were used in order to match data with the yearly utilization data sets. Utilization and cost data came from administrative records from Colorado's Department of Health Care Policy and Financing on the expenditures and utilization of services, plus primary psychiatric diagnoses; shadow billing data came from Colorado's Mental Health Service, which captures utilization data from community mental health centers postcapitation; and state hospital utilization data came from Colorado's Mental Health Service. The analyses presented here were based on three years of data (1994–1997)—one year precapitation and two years postcapitation. The utilization and cost data for inpatient, outpatient, and total services were aggregated on a yearly basis for three years.

The survey sample consisted of randomly selected consumers from Colorado's 1994 Medicaid files and the 1995–1996 admission rolls from community mental health centers. Informed consent was obtained from all individuals, and the protocol for the study was approved by the University of California, Berkeley, Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects. The sample included consumers who were at least 18 years old in 1994 and who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder or at least one 24-hour inpatient stay in the past year. The sample was stratified by gender and prior-year Medicaid expenditures on the basis of the median of the distribution (low cost was below the median of $1,500 and high cost was from $1,500 to $85,000). Persons from rural areas (56 persons, or 8%) and persons new to the mental health system after capitation (105 persons, or 15%) were excluded from the analyses presented here because observations lacked data from both pre- and postcapitation periods. The remaining 522 individuals were those identified as Medicaid-eligible service users in the year before capitation. There was 92% retention for postcapitation year 1 and 91% retention for postcapitation year 2 ( 13 ).

Measurement

Social networks. Respondents were asked about their relationship with their family, relatives, and other people in their lives. An index of family relationships was created on the basis of how often the consumer talked to a family member on the telephone and how often the consumer got together with a family member in the past six months (Cronbach's α =.57). An index of relationships with close friends was created on the basis of whether the consumer had any close friends and the frequency with which they visited, telephoned, wrote a letter to, did something with, and spent time with their friends (Cronbach's α =.68). The questions came from Lehman's Quality of Life interview ( 14 ). Responses to the frequency of contact were dichotomized so that responses of "not at all" or "less than once a month" were coded as a 0 and responses of greater frequency, that is, contacts "at least once per month" or more were coded as a 1. These two indexes were combined to create the social network index (Cronbach's α =.66) in which consumers were grouped into nine ordinal categories, where 0 represents the lowest network level and 8 represents the highest network level. This measure is similar to the Berkman and Syme's social network index ( 15 ).

Service utilization and expenditures. Utilization was measured for three different services: inpatient psychiatric services in local hospitals, inpatient services in state psychiatric hospitals, and outpatient services defined as any noninpatient services. Expenditures for inpatient services in local hospitals and in state hospitals and outpatient services were calculated on the basis of the expenditures data from the Medicaid claims before capitation and shadow billing data after capitation.

Other covariates. Age was used as a continuous variable in the study. Gender was measured as a dichotomous variable. Ethnicity was divided into white and nonwhite (black, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American, and other). The utilization data included a primary diagnosis for each consumer. On the basis of those data, clinical diagnoses were categorized into three groups: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or other diagnosis. Finally, the model included a dichotomous capitation variable comparing individuals who received services through capitated mental health agencies with those who remained in the fee-for-service system and a time variable indicating pre- and postcapitation periods.

Analysis

A two-step regression procedure was used to examine the relationship between social network variables and mental health service use and expenditures. In this study mental health service use and expenditures were the outcome variables of interest, and the social network index was the main predictor variable. To maximize power, the number of covariates in the model was limited. The model included sociodemographic variables (age, the square of age, gender, and ethnicity), high- and low-cost variables, diagnosis variables (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other diagnosis), type of reimbursement (capitation or fee-for-service model), and time (precapitation year, postcapitation year 1, and postcapitation year 2).

In the first step, the dependent variable for each service category was transformed to a binary variable with a unit value of 1 if the consumer used any services in each one-year period and 0 if the consumer did not use any services. These variables were developed for each of the three service categories: inpatient services in local hospitals, inpatient services in state psychiatric hospitals, and outpatient services. Logistic regression was used to estimate the dependent variable model. In the second part of the analyses, ordinary least-squares regression was used to model the effect of independent variables on the logarithm of expenditures for each service category conditional on service utilization.

A time variable that classified the period before and after capitation and a variable that classified the type of reimbursement were entered in both logistic and ordinary least-squares models. Interaction terms of the social network index with time and capitation, respectively, were also used. These interaction terms were not significantly associated with utilization of and expenditures for inpatient services in local hospitals, inpatient services in state hospitals, and outpatient services. There was an insufficient number of consumers with bipolar disorder who utilized inpatient services in state hospitals. For this reason, the model for state hospital utilization and expenditures excluded diagnosis variables. All the analyses were performed by using the SAS software program ( 16 ).

Results

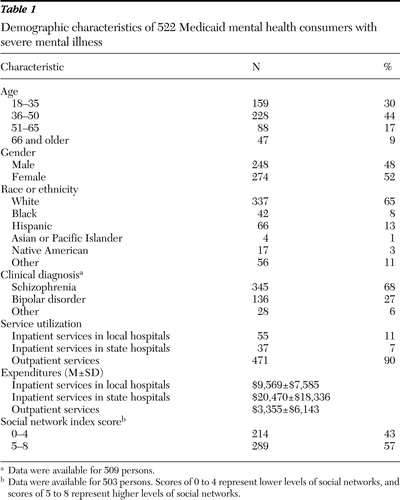

Sociodemographic characteristics and the distribution of the social network index for the sample are shown in Table 1 . Most consumers were white (65%), and consumers were almost equally divided between men and women. Seventy-four percent of the sample was between 18 and 50 years of age. Sixty-eight percent of the sample had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The social network index was well distributed; it ranged from 0 to 8, with 43% of index scores falling between 0 and 4.

|

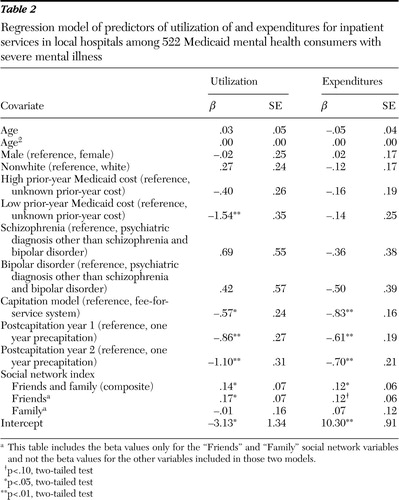

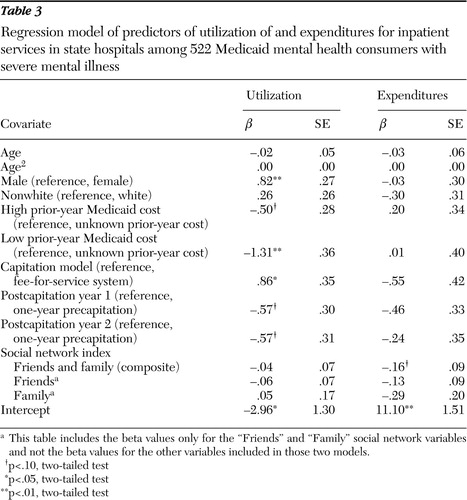

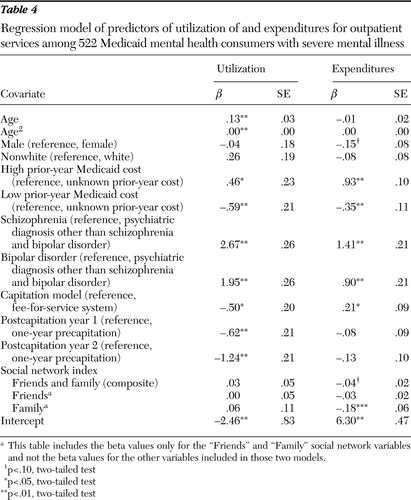

The results of the models for utilization of and expenditures for inpatient services in local hospitals, inpatient services in state hospitals, and outpatient services are presented in Tables 2 , 3 , and 4 , respectively. The significant effects of the capitation model and time on inpatient services in local hospitals, inpatient services in state hospitals, and outpatient service utilization and expenditures confirm those published in a previous study ( 12 ). Specifically, capitated financing in community mental health centers in Colorado was associated with a consistent reduction in the utilization of inpatient services in local hospitals and outpatient services, with significant reductions in expenditures related to inpatient services in local hospitals in the first-year postcapitation and outpatient services in the second-year postcapitation. Even after the analysis controlled for the effects of capitation on service utilization, there was a significant effect of social network. The social network index was positively associated with utilization of inpatient services in local hospitals but was not associated with the utilization of inpatient services in state hospitals or outpatient services. The social network index was positively associated with the expenditures for inpatient services in local hospitals but negatively associated with the expenditures for inpatient services in state hospitals or outpatient services.

|

|

|

Because the social network index is a composite of two sets of relationships—that is, friends and family members—each component was analyzed separately to determine its respective contributions to mental health services utilization and expenditures. Relationships with family were not associated with the utilization of psychiatric inpatient services in local hospitals, inpatient services in state hospitals, or outpatient services. Relationships with family, however, were negatively related to expenditures for outpatient services but not for inpatient services in local or state hospitals. Relationships with friends were positively associated with utilization of and expenditures for psychiatric inpatient services in local hospitals but were not associated with utilization of or expenditures for inpatient services in state hospitals or outpatient services.

Discussion

The results were consistent with our hypothesis that social networks are associated with mental heath utilization and expenditures. Consumers who had higher social network index scores were more likely to use and have higher expenditures for inpatient services in local hospitals. However, consumers who had higher social network index scores had lower expenditures for inpatient services in state hospitals and outpatient services. Furthermore, there was a significant relationship between social network index scores and utilization and expenditures even after the analysis controlled for capitation and prior-year service expenditures, confirming that social networks play an important and independent role in mental health service utilization and access.

When the social network index was broken down into its two components, family relationships were related only to lower outpatient service expenditures. The relationships with friends were related to greater utilization of and expenditures for inpatient services in local hospitals but were not related to the utilization of and expenditures for inpatient services in state hospitals or outpatient services. Findings on utilization of inpatient services in local hospitals are particularly important because consumers are more likely to use a local hospital than a state hospital if they have a crisis and need immediate hospitalization ( 17 ). Given a choice between state and local hospitals, those with larger social networks may be more likely to remain in the community and, therefore, would be more likely to use inpatient services in local hospitals. Our findings confirm this hypothesis for the composite social network and the social network composed of friends. Our findings suggest that families play an important role in the types of outpatient services and may serve as substitutes for more expensive types of outpatient therapy, thereby reducing outpatient expenditures. Differences in the relationship between the two types of social networks (those composed of friends and those composed of family) and utilization of services suggest that the type of aid received from these two types of social networks may be qualitatively different.

The findings between the two types of social networks do not display a consistent pattern across the types of services. Some findings are consistent with the hypothesis that social networks substitute for mental health services, mitigating utilization of formal services ( 18 ). Other findings are consistent with the hypothesis that social networks facilitate utilization, perhaps through advocacy or referral to services ( 19 ) or by transmitting values that decrease stigma and encourage service utilization. Future research should focus on the qualitative aspects of social networks and the mechanisms by which social networks influence service utilization.

The study presented here has several limitations. First, the operationalization of social network in this study was based on the number of family members and friends and on how often the consumer had contact with them. Because of the aims of the larger evaluation study, the social network definition used in this study is a structural one and does not provide information on the qualitative, functional aspects of social ties. Future research should focus more on the different perceived functions of social networks and their contributions to the utilization and cost of mental health services. In addition, the internal reliability of the social network indices used in this study is low. Future research should incorporate other measures of social networks to improve internal reliability.

Second, the findings of this study represent associations and not causal implications. It is possible that there is an endogenous relationship between the social network index and service utilization, such that utilization of specific services influences the nature of individuals' social networks. The study presented here lacks the sample size and instrumental variables to conduct an appropriate investigation of potential endogeneity. However, analyses using a subsample of individuals with consistent social network index scores (85% of the sample) one year precapitation and one year postcapitation revealed findings identical to those presented here and support the finding that social networks influence utilization and expenditures.

Third, the generalizability of findings is limited to adult Medicaid beneficiaries with severe mental illness. The sample used in this study may not represent the general population of mental health consumers. Inclusion of mental health providers within the social network may be more prevalent among those with severe mental illness and may influence service utilization, although studies have reported mixed results ( 2 , 7 ). This study did not exclude categorization of service providers as "friends." Moreover, particular types of social network involvement and needs for mental health services may be specific to Medicaid mental health consumers and may not be generalizable to non-Medicaid mental health consumers or Medicaid consumers with predominantly physical versus mental health problems.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that social networks may moderate mental health service utilization. Our findings suggest that social networks and service use may be important considerations in the construction of interventions. A growing body of literature supports the use of family psychoeducation and caregiver support to address and alleviate alienation among persons with severe mental illness ( 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ). Future studies should investigate the impact of social network interventions on service utilization and clinical outcome measures and the interaction of social network interventions on psychosocial and social network qualities. The reasons why family relationships were more important in lowering expenditures for outpatient services and why friend relationships were more important in utilization of and expenditures for inpatient services in local hospitals are not clear and require further investigation. Future investigations of various functions of the social network, such as emotional, informational, and financial support, will be necessary to understand how social networks influence utilization of specific types of mental health services.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was funded by grant R01-MH-54136 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Becker T, Albert M, Angermeyer MC, et al: Social networks and service utilisation in patients with severe mental illness. Epidemiologia e Psychiatria Sociale 6:113–125, 1997Google Scholar

2. Albert M, Becker T, McCrone P, et al: Social networks and mental health service utilization—a literature review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 44:248–266, 1998Google Scholar

3. Brown D, Gary L: Stressful life events, social support networks, and the physical and mental health of urban black adults. Journal of Human Stress 13:165–174, 1987Google Scholar

4. Olstad R, Sexton H, Sogaard A: The Finnmark study: social support, social network, and mental distress in a prospective population study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:519–525, 1999Google Scholar

5. Gourash N: Help-seeking: a review of the literature. American Journal of Community Psychology 6:413–423, 1978Google Scholar

6. Bloom J, Fobair P, Spiegel D, et al: Social supports and the social well-being of cancer survivors, in Advances in Medical Sociology. Edited by Albrecht G. New York, JAI Press, 1991Google Scholar

7. Meeks S, Murrell SA: Service providers in the social networks of clients with severe mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 20:399–406, 1994Google Scholar

8. Macdonald E, Hayes R, Baglioni A: The quantity and quality of the social networks of young people with early psychosis compared with closely matched controls. Schizophrenia Research 46:25–30, 2000Google Scholar

9. Bengtsson-Tops A, Hansson L: Quantitative and qualitative aspects of the social network in schizophrenic patients living in the community: relationship to sociodemographic characteristics and clinical factors and subjective quality of life. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 47:67–77, 2001Google Scholar

10. Hamilton N, Ponzoha C, Cutler D, et al: Social networks and negative versus positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 15:625–633, 1989Google Scholar

11. Magliano L, Fiorillo A, Malangone C, et al: Social network in long-term diseases: a comparative study in relatives of persons with schizophrenia and physical illnesses versus a sample from the general population. Social Science and Medicine 62:1392–1402, 2006Google Scholar

12. Bloom J, Hu T, Wallace N, et al: Mental health costs and access under alternative capitation systems in Colorado. Health Services Research 37:315–339, 2002Google Scholar

13. Cuffel B, Bloom J, Wallace N, et al: Two-year outcomes of fee-for-service and capitated Medicaid programs for the severely mentally ill. Health Services Research 38:341–360, 2002Google Scholar

14. Lehman A: Measuring quality of life in a reformed health system. Health Affairs 14(3):90–101, 1995Google Scholar

15. Berkman LF, Syme SL: Social networks, host resistance and mortality: a nine year follow-up of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology 109:186–204, 1979Google Scholar

16. SAS, Version 8. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 2000Google Scholar

17. Belcher J, DeForge B: The failure of the diversion process: the impact of transferring of patients to state hospitals. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:286–292, 1995Google Scholar

18. Cohen CI, Magai C, Yaffee R, et al: Comparison of users and non-users of mental health services among depressed, older, urban African Americans. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 13:545–553, 2005Google Scholar

19. Carpentier N, White D: Cohesion of the primary social network and sustained service use before the first psychiatric hospitalization. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research 29:404–418, 2002Google Scholar

20. Perese EF, Wolf M: Combating loneliness among persons with severe mental illness: social network interventions' characteristics, effectiveness, and applicability. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 26:591, 2005Google Scholar

21. Biegel D, Tracy E, Song L: Barriers to social network interventions with persons with severe and persistent mental illness: a survey of mental health case managers. Community Mental Health Journal 31:335–349, 1995Google Scholar

22. Vieta E, Pacchiarotti I, Scott J, et al: Evidence-based research on the efficacy of psychologic interventions in bipolar disorders: a critical review. Current Psychiatry Reports 7:449–455, 2005Google Scholar

23. Murray-Swank A, Dixon L: Family psychoeducation as an evidence-based practice. CNS Spectrum 9:905–912, 2004Google Scholar

24. Kopelowicz A, Liberman RP: Integration of care: integrating treatment with rehabilitation for persons with major mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services 54:1491–1498, 2003Google Scholar

25. Miklowitz DJ, George EL, Richards JA, et al: A randomized study of family-focused psychoeducation and pharmacotherapy in the outpatient management of bipolar disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:904–912, 2003Google Scholar

26. McFarlane W, Dixon L, Lukens E, et al: Family psychoeducation and schizophrenia: a review of the literature. Journal of Marital Family Therapy 29:223–245, 2003Google Scholar

27. Liberman DB, Liberman RP: Involving families in rehabilitation through behavioral family management. Psychiatric Services 54:633–635, 2003Google Scholar

28. Stewart S, Vandenbroek AJ, Pearson S, et al: Prolonged beneficial effects of a home-based intervention on unplanned readmissions and mortality among patients with congestive heart failure. Archives of Internal Medicine 159:257–261, 1999Google Scholar