Connectedness and Citizenship: Redefining Social Integration

Despite decades of deinstitutionalization and the best efforts of community mental health services, individuals with psychiatric disabilities living outside the hospital may be described as in the community, but not of it. They may live in neighborhoods alongside people without disabilities. Their residences may resemble those of their neighbors. Yet many people who are psychiatrically disabled lack socially valued activity, adequate income, personal relationships, recognition and respect from others, and a political voice. They remain, in a very real sense, socially excluded.

In recent years, explication of the biological underpinnings of mental illness has been the major research preoccupation in psychiatry, all but eclipsing inquiry into social dimensions. The new discourse on recovery ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ) leads inevitably to recognition of social exclusion as a persisting problem for those working to rebuild their lives after the onset of mental illness. To address social exclusion, conceptual tools delineating not only the problem but also its solution are required. To help develop such tools, we offer here a new definition of the concept of social integration.

Previous conceptual work

Previous efforts in psychiatry to conceptualize social integration, while constructive, have incompletely captured its social dimensions, instead overemphasizing location and functioning as indicators. Reflecting the goals of deinstitutionalization, location has referred principally to residence outside the psychiatric hospital. "Amount of time spent in the community" is one well-known, location-focused definition ( 6 ). Functioning refers, in contrast, to the ability to sustain oneself outside the hospital. Functioning includes use of everyday goods and services and fulfillment of social roles. An example of a functioning-oriented definition is "making independent purchases and money management" ( 6 ).

Social dimensions of disability have in fact been the subjects of vigorous debate, but largely outside psychiatry. Social role valorization theory, originating in the study of developmental disabilities, pinpoints ways in which people with disabilities have been devalued by society, and it advocates, in response, greater access to valued social roles. Social role valorization theory is principally concerned with improving the experience of individuals who are disabled ( 7 , 8 , 9 ). The social model of disability, in contrast, emphasizes analysis of society. Grounded in the social sciences, this way of thinking locates disability not in the individual but in the barriers to individual accomplishment that disabling social structures, policies, and practices present ( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ). Social change, rather than valued roles, is what social model analysis calls for.

Proponents of the social role valorization theory and social model positions have historically been at odds. However, efforts to bring the two together are beginning to appear ( 14 ). Both the debate and the social model perspective have, up to now, remained external to thinking about social integration and psychiatric disability, however. Only social role valorization theory appears to be referenced in the mental health services research literature ( 15 ).

The capabilities approach as a conceptual framework

The capabilities approach to human development provides the conceptual framework for the research reported here. Grounded in development economics and moral philosophy, the capabilities approach is a way of organizing thinking, research, and measurement to more dynamically represent quality of life. Until recently the capabilities approach has been applied chiefly to the study of standards of living for disadvantaged populations living in developing countries ( 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ). Now, increasingly, it is being put to other uses, including the rethinking of disability and disparities in health ( 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ).

Conceived as an alternative to paradigms emphasizing satisfaction and income as quality-of-life indicators, the capabilities framework takes as its measure of quality degree of human agency—what people can actually do and be in everyday life. What people can do and be is in turn contingent on having competencies and opportunities. Opportunities are provided by social environments. To ensure capability, social circumstances must offer opportunities for individual competency to be developed and exercised. To define social integration, we borrow from the capabilities approach its emphasis on agency, its developmental perspective, its recognition that individual development is contingent on supportive social environments, and its core concepts of competency and opportunity in delineating the process through which social integration develops.

This article results from an anthropologically informed, qualitative study that aimed to define social integration in the context of psychiatric disability, construct a conceptual model depicting social integration processes, and develop an empirically derived theory that explains how social integration takes place. This article addresses the first aim: providing the definition.

Methods

Data collection

The study design called for two types of data collection: individual interviews and brief ethnographic visits. Individual interviewees were adults who had been psychiatrically disabled but who had become more socially integrated since disablement. Deciding who qualified as having become more socially integrated presented a problem, given that defining integration was a goal of the study. We relied on relevant concepts of social integration extant in the social science literature (such as multiple roles [ 26 ]) to select interviewees from volunteers. Brief ethnographic visits were short stays at service sites that, in the judgment of the investigators, work to promote social integration for persons who are psychiatrically disabled. Judgments as to appropriate sites were made from the collective experience of the research team, written information, and preliminary site visits. We obtained informed consent from study participants, using a form approved by the institutional review boards of Harvard Medical School and the Nathan S. Kline Institute. Data were collected in four U.S. states and Canada from 2003 to 2005.

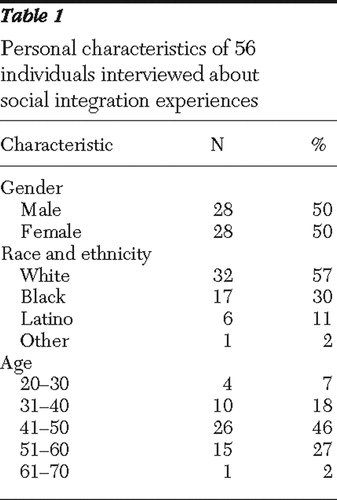

Individual interviews. This article draws upon data from 78 individual interviews conducted with 56 interviewees. The interviews were unstructured but aimed at eliciting detailed accounts of experiences of social integration. That is, we explored with interviewees aspects of their lives that promised to enhance our understanding of integration in subsequent analyses. We did not ask interviewees to address social integration directly. The interview was introduced differently depending on the individual and the situation. We asked how, for example, they started to improve or how things had changed since they started to improve. Interviews were conducted in two-person teams, an approach we have found helpful in enhancing data quality when interviewing individuals with severe mental illness ( 27 ). The interviews took place in homes and service settings and ranged from one to two hours in length. When initial conversations proved especially relevant and revealing, a second interview was scheduled. All of the investigators (also the authors) conducted interviews, which were audiorecorded and professionally transcribed. Characteristics of interviewees are presented in Table 1 .

|

Brief ethnographic visits. Data from eight brief ethnographic visits were also used to develop the new definition. The purpose of the visits was to understand through direct exposure how the selected programs contributed to social integration for their users. Visits lasted one to two days and consisted of interviews and field observations. Interviews conducted as part of ethnographic visits were unstructured and took place both individually and in groups. They focused on interviewee experiences and perceptions of the program and emphasized elicitation of concrete details (such as illustrative case studies and stories about events). Service users and providers were included in these interviews. Observations ranged from simple witnessing (of clinical encounters, for example) to active participation in program activities (such as a drama workshop). All of the investigators took part in ethnographic visits. After each visit a debriefing session was convened in which individual researchers reported on their experiences and shared understandings of what they had observed. Differences in understandings were identified and examined. The eight visits were made to five programs—a psychiatric rehabilitation program, a consumer-run drop-in center that teaches social skills, a therapeutic community, a residential and employment program aimed at "redefining community," and a community-based center for the treatment of young adults with psychosis.

Data analysis

To redefine social integration, we used an interpretive approach to analysis informed by the capabilities approach and aimed at articulating the meaning of the data ( 28 , 29 ). That is, we drew collectively on data-collection experiences to construct categories that would specify social integration for persons disabled by mental illness. We read interview transcripts and discussed both the transcripts and the eight ethnographic visits at face-to-face, day-long meetings of the research team and in telephone conferences. Twenty-three meetings and phone conferences took place over 2.5 years. In these discussions, excerpts from interview data and experiences from the ethnographic visits were examined for insights into the meanings of social integration an adequate definition would have to include. These empirically derived meanings were then examined in relation to the capabilities approach. Those selected for the definition were labeled, defined, and illustrated to form constituent categories—accountability, reliability, and empathy, for example. These categories were then grouped into larger categories that became the definition's core: connectedness and citizenship.

Results

On the basis of this analysis, we have defined social integration as a process, unfolding over time, through which individuals who have been psychiatrically disabled increasingly develop and exercise their capacities for connectedness and citizenship.

By connectedness, we mean the construction and successful maintenance of reciprocal interpersonal relationships. These relationships provide not only companionship and good feeling but also access to resources. They include persons without psychiatric disabilities who are outside the mental health system as well as those with disabilities. Interpersonal connectedness, as we envision it, extends well beyond receipt of social support.

Social, moral, and emotional competencies are required to sustain interpersonal connectedness. Social competencies refer here to effective communication—the ability to articulate thoughts and feelings in ways that engage others and make oneself understood. Moral competencies are the basis of trust—for example, accountability, reliability, credibility, and honesty. Empathy and a capacity for commitment are examples of emotional competencies for connectedness.

Social currency is also essential to connectedness. Social currency is that stock of personal attributes that sparks others' interests in connecting. Knowledge, talents, interpersonal style (for example, warmth, humor, and genuineness), and physical characteristics (attractiveness, for example) are forms of social currency. Social currency and competencies for connectedness are impaired by experiences associated with severe mental illness and psychiatric disability.

Connectedness also means identifying with a larger group. Connectedness in this sense is subjective—the feeling of being part of a whole. Identification is based on the perception of "having things in common with" others and leads to the sense that one has a stake in (is personally affected by) what happens in and to the group. Part of what social integration means for persons who have been psychiatrically disabled is increasing identification with groups not defined by mental illness.

Citizenship refers to the rights and privileges enjoyed by members of a democratic society and to the responsibilities these rights engender. The rights of U.S. citizens are protected by the Constitution (for example, basic civil rights) and by statute. Our responsibilities are to obey the law, participate in public discourse and decision-making processes, and contribute to the common good. Historically, the rights of persons with psychotic illness have been restricted on the grounds of mental incompetence, reducing them to second-class citizens or citizens of programs serving "special populations" ( 30 ). On the same grounds, they have been exempted from social and personal responsibility. Our definition of social integration calls for full rights and responsibilities of citizenship. By including the idea of citizenship, we acknowledge social integration's political dimension.

Discussion

Several attributes of this definition should be made explicit. First, it posits growth and development, rather than stabilization, as the object of psychiatric treatment for persons disabled by mental illness. Flourishing, not simply functioning, is the envisioned outcome. Second, this formulation casts persons with psychiatric disabilities as agents rather than—to invoke a current construction—"consumers." Third, the definition overlaps with conceptualizations of recovery from mental illness that depict social exclusion as at least part of what is being recovered from and acknowledge the social character of the recovery process ( 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ). The considerable variability in how recovery is defined underscores the value of clearly delineating the relationship between the two concepts.

The idea that meaning has a rightful role to play in thinking about outcomes of mental health treatment is also reintroduced in the definition. In recent years, psychiatry has largely ignored the fact that "making meaning" can be as important as controlling symptoms in treating persons with severe mental illness. To "make meaning" is to learn to interpret or reinterpret one's experience, to find a reason for living, or to succeed in living a worthy life. One way of staking a claim to worthiness is by making the social contributions of citizenship.

This is personal meaning-making. Definitions also make meaning for analysts working to understand social problems—and from those understandings, craft solutions ( 37 ). To define a social problem is not simply to specify a particular segment of reality; it is a choice with implications. For example, if we define homelessness as chiefly a problem of "housing readiness" for people living on the streets or in shelters, then corrective measures will be devoted to repairing the deficits of individuals. If, alternatively, we define it as an insufficient supply of residential options, then remedies will target specific resource scarcities. The two definitions trace the origins of the problem to different sources—people versus housing—with differing implications for policy ( 38 ). Similarly, recovery from mental illness can be construed as the disappearance of symptoms, as living well with symptoms, or as social integration. The definition chosen determines "what counts" as recovery-oriented policies and services.

Rethinking social integration from a capabilities perspective means considering not only individual quality of life but also required social change. Required social changes are of at least two types: the reduction of societal barriers to integration and the creation of opportunities for social participation. Reduction of barriers can be accomplished by refining accommodations presently available to persons with psychiatric disabilities and by reworking social structures—for example, the Social Security insurance system that creates disincentives for beneficiaries wishing to end dependence on entitlements and support themselves through earned income. A test to demonstrate the effects of eliminating Social Security disincentives (in conjunction with work and treatment supports) on employment outcomes for persons with schizophrenia and affective disorders is, in fact, under way (Frey W, Drake R, Goldman H, et al., unpublished manuscript).

Opportunities for social integration include those aimed at developing competencies and those that allow competencies to be exercised. Providing opportunities for competency development lies within the scope of mental health services; creating opportunities for exercising competencies falls to the larger society.

Competencies for social integration differ from those targeted by rehabilitation efforts in that they address obstacles to inclusion rather than illness-related impairments. Literacy—competence in reading, writing, and the use of computers—is an example of an integration-oriented competency. Education for literacy is one form that services aimed at developing competencies for integration might take. The literacy example also highlights the value of cross-sector collaborations in creating opportunities for competency development. Some requisite general characteristics of such opportunities include assumption of competence or potential competence on the part of persons served, emphasis on socially valued activities, an "action first" approach (as in supported employment's "place-train" rather than "train-place" approach), and a tolerance for risk.

What are other service implications of a capabilities approach to social integration? The emphasis on agency invites a reexamination of the ideas underlying existing clinical and service paradigms. History teaches us that what may appear at one point in time to be "truths" about the limited capacities of population subgroups—women or African Americans in the United States, for example—may later be revealed to be unfounded assumptions. The "truth" about the inevitably chronic course of schizophrenia is already being recast in a similar way ( 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ). What if other aspects of the meaning of mental illness were subjected to similar scrutiny?

The meaning of social integration is not different for different people. Accordingly, our definition applies to persons with and without psychiatric disabilities and represents an ideal. Connectedness and citizenship as depicted here are ends to which we all, to varying degrees, aspire but never completely achieve. Different experiences place people at different distances from these ends. Individuals socially marginalized through psychiatric disability find themselves relatively far removed from the integration ideal.

In developing this definition, we have borrowed not only from the capabilities perspective but also from contemporary writings in psychiatry. For example, social integration figures explicitly in a comprehensive approach to treating psychotic illness developed by Apollon and colleagues ( 44 , 45 ), where it has two different meanings. A set of interpersonal relationships—"connectedness" in this study—is the first. The second refers to a moral position in which the individual accepts responsibility for the way the world is and through a unique "social project" makes an effort to change it for the better ( 46 ; Apollon W, ethnographic interview, 2005). This moral position links the individual to the larger society and informs our use of the idea of citizenship.

In planning research on social integration, the initial inclination is perhaps to think of it as an outcome. However, the definition offered here is deliberately process oriented. By emphasizing process, we call attention to the importance of understanding not just what predicts social integration but how it happens. An understanding of process will likely contribute most directly to efforts by mental health services to enhance social integration for persons with psychiatric disabilities.

One immediate use we might make of this definition and the capabilities framework that informs it is to begin to formulate ensuing research questions. We propose the following examples, which, although far reaching, can be made operational in various ways once they are clearly stated. Mental health services researchers might reasonably ask, for instance, what competencies for connectedness and citizenship persons with psychiatric disabilities presently possess? What opportunities are available to them? An investigation stemming from such questions would stand in stark contrast to inquiries eliciting, for example, consumer satisfaction and preferences. It lays the foundation to ask what opportunities for developing competencies for social integration should look like. Model development is another clear next step in this conceptual project and is needed to guide empirical investigations.

Models help us to organize indeterminate realities and develop valid measures of connectedness and citizenship. For guidance in measure development, we may also look to social science. Social network methods provide good starting points for thinking about the assessment of connectedness. These methods have a distinguished history in social science and in health research ( 47 ), one that includes studies of persons with severe mental illness ( 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 ). Studies of civic traditions of participation ( 59 , 60 ), public deliberation ( 61 , 62 ), and conditions of citizen engagement more generally ( 63 ) promise to inform the development of measures of citizenship.

Conclusions

We have used the capabilities approach to frame social integration in terms of agency and quality of life. Quality of life is a familiar construct to most clinicians and mental health services researchers. Here we have altered its meaning from one circumscribed by impairments and limitations (and informed by a "chronicity" model of the course of severe mental illness) to one that focuses on possibilities for development and growth. Our definition of social integration sets an ideal, but not unrealistic, standard. In setting standards high, we encourage readers to rethink what is possible for mental health services and to raise expectations for connectedness and citizenship among persons once disabled by mental illness.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The research reported here is supported by grant R01-MH-065247 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The able assistance of Madeleine Smith, M.S.W., in the preparation of this manuscript is gratefully acknowledged. The authors thank Leon Eisenberg, M.D., and Robert E. Drake, M.D., Ph.D., for helpful critiques of draft versions of this article, and they thank the participants in this study.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

2. Jacobson N: In Recovery: The Making of Mental Health Policy. Nashville, Tenn, Vanderbilt University Press, 2004Google Scholar

3. Mueser KT, Corrigan PW, Hilton DW, et al: Illness management and recovery: a review of the research. Psychiatric Services 53:1272–1284, 2002Google Scholar

4. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A: Recovery from schizophrenia: a concept in search of research. Psychiatric Services 56:735–742, 2005Google Scholar

5. Resnick SG, Rosenheck RA, Lehman AF: An exploratory analysis of correlates of recovery. Psychiatric Services 55:540–547, 2004Google Scholar

6. Segal SP, Aviram U: The Mentally Ill in Community-Based Sheltered Care. New York, Wiley, 1978Google Scholar

7. Wolfensberger W: Social role valorization: a proposed new term for the principle of normalization. Mental Retardation 21:234–239, 1983Google Scholar

8. Wolfensberger W: A Brief Introduction to Social Role Valorization: A High-Order Concept for Addressing the Plight of Societally Devalued People and for Structuring Services. Syracuse, NY, Syracuse University, Training Institute for Human Service Planning, Leadership and Change Agentry, 1998Google Scholar

9. Wolfensberger W: A brief overview of social role valorization. Mental Retardation 38:105–123, 2000Google Scholar

10. Fundamental Principles of Disability. London, Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation, 1976Google Scholar

11. Oliver M: The Politics of Disablement. Basingstoke, United Kingdom, Macmillan, 1990Google Scholar

12. Oliver M: Understanding Disability: From Theory to Practice. Basingstoke, United Kingdom, Macmillan, 1996Google Scholar

13. Barnes C: The Social model of disability: a sociological phenomenon ignored by sociologists? in The Disability Reader: Social Science Perspectives. Edited by Shakespeare T. London, Cassell, 1998Google Scholar

14. Race D, Boxall K, Carson I: Towards a dialogue for practice: reconciling social role valorization and the social model of disability. Disability and Society 20:507–521, 2005Google Scholar

15. Wong Y-L, Solomon PL: Community integration of persons with psychiatric disabilities in supportive independent housing: a conceptual model and methodological considerations. Mental Health Services Research 4:13–28, 2002Google Scholar

16. Sen AK: Equality of what? in Tanner Lectures on Human Values. Edited by McMurrin S. Cambridge, United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 1980Google Scholar

17. Sen A: Commodities and Capabilities. Oxford, United Kingdom, North-Holland, 1985Google Scholar

18. Sen AK: Inequality Re-examined. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1992Google Scholar

19. Sen AK: Development as Freedom. New York, Knopf, 1999Google Scholar

20. Nussbaum MC: Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach. Cambridge, United Kingdom, University of Cambridge Press Syndicate, 2000Google Scholar

21. Nussbaum M, Sen A: The Quality of Life. Oxford, United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, 1993Google Scholar

22. Ruger JP: Health and social justice. Lancet 364:1075–1080, 2004Google Scholar

23. Nussbaum M: Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 2006Google Scholar

24. Olson K: Distributive justice and the politics of difference. Critical Horizons 2:5–32, 2001Google Scholar

25. Burchardt T: Capabilities and disability: the capabilities framework and the social model of disability. Disability and Society 19:735–751, 2004Google Scholar

26. Thoits PA: Multiple identities and psychological well-being: a reformulation and test of the social isolation hypothesis. American Sociological Review 48:174–187, 1983Google Scholar

27. Ware NC, Tugenberg T, Dickey B: Practitioner relationships and quality of care for low-income persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:555–559, 2004Google Scholar

28. Geertz C: The Interpretation of Cultures. New York, Basic Books, 1973Google Scholar

29. Denzin NK: The art and politics of interpretation, in Handbook of Qualitative Research. Edited by Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1994Google Scholar

30. Rowe M: Crossing the Border. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1999Google Scholar

31. Warner R: Recovery From Schizophrenia: Psychiatry and Political Economy. London, Routledge, 1994Google Scholar

32. Ahern L, Fisher D: Recovery at your own PACE. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing 39:22–32, 2001Google Scholar

33. Jacobson N, Greenley D: What is recovery? A conceptual model and explication. Psychiatric Services 52:482–485, 2001Google Scholar

34. Breier A, Strauss JS: The role of social relationships in the recovery from psychotic disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 141:949–955, 1984Google Scholar

35. Anthony WA: Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990's. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16:11–23, 1993Google Scholar

36. Spaniol L, Bellingham R, Cohen B, et al: The Recovery Workbook: II. Connectedness. Boston, Boston University, Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 2003Google Scholar

37. Hopper K: Homelessness old and new: the matter of definition. Housing Policy Debate 2:757–813, 1991Google Scholar

38. Tsemberis S, Eisenberg RF: Supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 51:487–493, 2000Google Scholar

39. Hopper K, Harrison G, Janca A, et al: Recovery From Schizophrenia—An International Perspective. New York, Oxford University Press, 2007Google Scholar

40. Leff J, Sartorius N, Jablensky A, et al: The international pilot study of schizophrenia: five-year follow-up findings. Psychological Medicine 22:131–145, 1992Google Scholar

41. Harrison F, Hopper K, Craig T, et al: Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. British Journal of Psychiatry 178:506–517, 2001Google Scholar

42. Harding CM, Brooks GM, Ashikaga T, et al: The Vermont longitudinal study of persons with mental illness: I. methodology, study sample, and overall status 32 years later. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:718–726, 1987Google Scholar

43. Harding CM, Brooks GW, Ashikaga T, et al: The Vermont longitudinal study of persons with mental illness: II. long-term outcome of subjects who retrospectively met DSM-III criteria for schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:727–735, 1987Google Scholar

44. Apollon W, Bergeron D, Cantin L: Psychoanalysis and the treatment of psychotics, in Treating Psychosis [in French]. Edited by Apollon W, Bergeron D, Cantin L. Quebec City, Quebec, GIFRIC, 1990Google Scholar

45. Apollon W, Bergeron D, Cantin L: The treatment of psychosis, in The Subject of Lacan: A Lacanian Reader for Psychologists. Edited by Malone KR, Friedlander SR. Albany, NY, SUNY Press, 2000Google Scholar

46. Cantin L: The treatment of the crisis and the questioning of the delusional enterprise. Presented at the annual meeting of the International Federation for Psychoanalysis Education, Chicago, Nov 2004Google Scholar

47. Bott E: Family and Social Networks: Roles, Norms and External Relationships in Ordinary Urban Families. London, Tavistock, 1957Google Scholar

48. Wellman B: Networks in the Global Village: Life in Contemporary Communities. Boulder, Colo, Westview Press, 1999Google Scholar

49. Fischer CS: To Dwell Among Friends: Personal Networks in Town and City. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1982Google Scholar

50. Granovetter MS: The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology 78:1360–1380, 1973Google Scholar

51. Berkman LF, Syme SL: Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology 109:186–204, 1979Google Scholar

52. Loucks EB, Sullivan LM, D'Agostino RB Sr, et al: Social networks and inflammatory markers in the Framingham Heart Study. Journal of Biosocial Science 38:835–842, 2006Google Scholar

53. Pescosolido BA, Wright ER, Alegria M, et al: Social networks and patterns of use among the poor with mental health problems in Puerto Rico. Medical Care 36:1057–1072, 1998Google Scholar

54. Lovell AM: Marginal Arrangements: Homelessness, Mental Illness and Social Relations. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Columbia University, Department of Sociomedical Sciences, Mailman School of Public Health, 1992Google Scholar

55. Becker T, Thornicroft G, Leese M, et al: Social networks and service use among representative cases of psychosis in South London. British Journal of Psychiatry 171:15–19, 1997Google Scholar

56. Becker T, Leese M, Clarkson P, et al: Links between social networks and quality of life: an epidemiologically representative study of psychotic patients in south London. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:299–304, 1998Google Scholar

57. Hammer M, Makiesky-Barrow S, Gutwirth L: Social networks and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 4:525–545, 1978Google Scholar

58. Estroff SE, Swanson JW, Lachicotte WS, et al: Risk reconsidered: targets of violence in the social networks of people with serious psychiatric disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:S95–S101, 1998Google Scholar

59. Bellah RN, Madsen R, Sullivan WM, et al: Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1985Google Scholar

60. Putnam RD, Leonardi R, Nanetti RY: Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1993Google Scholar

61. Fraser N: Unruly Practices: Power, Discourse, and Gender in Contemporary Social Theory. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1989Google Scholar

62. Bohman J: Public Deliberation: Pluralism, Complexity, and Democracy. Cambridge, Mass, Cambridge University Press, 1996Google Scholar

63. Flyvbjerg B: Making Social Science Matter: Why Social Inquiry Fails and How It Can Succeed Again. Cambridge Mass, Cambridge University Press, 2001Google Scholar