Psychological Distress Among Latino Family Caregivers of Adults With Schizophrenia: The Roles of Burden and Stigma

Research on Latino families who have a relative with mental illness (that is, the patient) has largely focused on how the family relates to the patient and how family attitudes and interactions may impact the patient ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ). Data suggest that Latino family caregivers are more likely to live with the patient, be more accepting and more hopeful for a cure ( 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ), and exhibit fewer critical comments toward the patient, compared with European-American families ( 1 , 2 , 3 ). These key cross-ethnic differences in caregiver involvement and affect may also reflect differences in the way that caregiving is linked with the course of schizophrenia. For example, low levels of caregiver warmth were a significant predictor of relapse among Latino patients but not among European-American patients ( 5 ).

Researchers continue to investigate how family caregiving among Latinos may affect patients' outcomes; however, it is equally important to attend to the well-being of family caregivers. A substantial body of research on families and mental illness has examined how caregiving processes are linked to the emotional health of family caregivers ( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ). A consistent pattern of findings underscores that more psychiatric symptoms of the patient, more behavior problems of the patient, and more caregiving demands are associated with higher levels of caregivers' feelings of burden and psychological distress.

However, there has been a paucity of research on the emotional health of Latino caregivers of a family member with mental illness. The few studies that have been conducted with Latino family caregivers have found that these caregivers experience burden and psychological distress at levels similar to those of European-American family caregivers ( 14 , 15 , 16 ). However, in studies of families caring for persons with other disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease, dementia, or mental retardation, Latino caregivers have consistently reported higher levels of depression than European-American caregivers ( 17 ).

Literature on Latino family caregivers and mental illness suggests that although Latino family caregivers are likely to be highly engaged and display warmth toward patients, the caregivers are also experiencing substantial stress and burden related to caregiving. Thus research is needed that focuses on Latino caregivers' emotional health.

In this study, we examined levels of depressive symptoms among Latino caregivers of family members with schizophrenia and the correlates of depressive symptoms in this population by using a stress-process model. In research on the emotional health of family caregivers of older adults, stress-process models have been used that include context variables (for example, demographic characteristics), stressors, and caregiver appraisals, such as subjective burden ( 18 , 19 ). Taking into account context variables, caregiving stressors (for example, patients' psychiatric symptoms) are hypothesized to impact caregivers' emotional distress both directly and through mediating factors, such as caregivers' appraisals ( 19 ).

Following this model, we hypothesized that stressors (patients' positive symptoms) would be related to caregivers' depressive symptoms after taking into account context variables (for example, demographic characteristics). Because positive symptoms are often linked with interpersonal conflict and disruption of daily routines, they can be considered objective stressors for family caregivers. Second, we hypothesized that caregivers' appraisals (subjective burden) would mediate the relation between patients' positive symptoms and caregivers' depressive symptoms. In other words, high levels of positive symptoms would be related to more burdensome appraisals by caregivers, which would, in turn, be related to higher levels of caregivers' depressive symptoms.

We also examined the role of caregivers' perceived stigma in the stress-process model. Stigma is characterized as a source of shame that is cast onto individuals with mental illness by society ( 20 , 21 ). Caregivers who have a relative with a high level of publicly conspicuous positive symptoms may also experience stigma and, in turn, higher levels of depressive symptoms. Hence, we hypothesized that stigma would be positively related to caregivers' psychological distress. Furthermore, stigma may have subjective appraisal components such that some family caregivers may appraise schizophrenia symptoms as being more stigmatizing than other family caregivers would rate them. Hence, we also hypothesized that stigma would mediate the relation between patients' symptoms and caregivers' depressive symptoms.

Sociodemographic correlates of depression among Latinos include socioeconomic status, female gender, older age, and marital status ( 22 , 23 ). Thus they were incorporated in this study as context variables.

Previous studies of family caregivers of persons with mental illness have examined the impact of psychiatric symptoms on stigma, subjective burden, and depression, each as separate outcomes. Our study makes a unique contribution to the literature on family caregivers by examining the role of caregivers' burden and stigma as mediators between patients' positive psychiatric symptoms and caregivers' depression. Furthermore, we examined these processes among Latinos, who have been underrepresented in caregiving burden research.

Research questions for the study presented here include the following. What characteristics of caregivers and patients (context variables) are related to caregivers' depressive symptoms? Are patients' psychiatric symptoms (stressors) as well as caregivers' burden and caregivers' stigma (appraisals) positively related to caregivers' depressive symptoms? Does burden, stigma, or both mediate the relation between caregivers' stressors (patients' psychiatric symptoms) and caregivers' depressive symptoms?

Methods

Participants and procedures

Participants were 85 dyads of primary family caregivers and their adult relatives with mental illness. Primary caregivers are those who provide the most care to the patient. Participants were recruited in two separate studies, one that was conducted in El Paso, Texas (N=45), and another that was conducted in Milwaukee, Wisconsin (N=13), and Los Angeles, California (N=27). Adult relatives with mental illness were diagnosed as having either schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. In El Paso diagnosis was determined by a clinician who administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-Bilingual Patient Edition ( 24 ). In the Milwaukee and Los Angeles study, diagnosis was confirmed by the psychiatrists that referred the patients. Both studies recruited participants from outpatient mental health clinics between 2001 and 2003. The outpatient clinics were all part of public community mental health centers. Thus they offered case management, psychiatric medication, and other outpatient-based programs. Such clinics are typically staffed with professionals with a bachelor's or graduate degree in human service fields—such as psychology and social work—and nursing and psychiatry. The services are used primarily by indigent persons with serious and persistent mental illness, whose service usage patterns vary substantially from each other and over time.

Potential participants were identified by mental health professionals who worked in community mental health programs or outpatient clinics. Participants were recruited by research teams that included mental health professionals and graduate students. The research teams informed patients or their parents about the study and asked if they would be interested in participating. Caregivers were interviewed in their home or at the mental health agency, according to their preferences. Interviews were conducted in the language of preference (Spanish or English) by bilingual and bicultural interviewers. Measures that were not already available in Spanish were translated by using back-translation methods ( 25 ). Study procedures were approved by the respective university institutional review boards and the professional review committees of the mental health clinics.

Measures

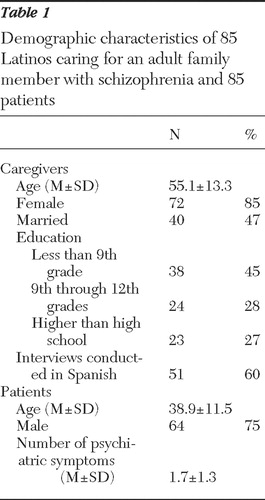

Caregivers' and patients' ages were continuous variables. Caregivers' education was measured by using a 6-point scale that ranged from 0, less than sixth grade, to 5, college graduate or higher. For easier interpretation in the table, education was recoded into three categories (less than ninth grade, ninth through 12th grades, and higher than high school); however, the full scale was used in the regression analyses. Although both studies included a comparable question measuring household income, there were significant missing data for this variable. Therefore, we did not use it in the analysis presented here. The following variables were coded as dichotomous variables: marital status: not married, 0, or married, 1; language of interview: English, 0, or Spanish, 1; and caregiver's and patient's gender: male, 0, or female, 1.

Psychiatric symptoms were measured by a count of four positive symptoms of schizophrenia: hallucinations and bizarre, hostile, or unusual behaviors. In the Milwaukee and Los Angeles samples the symptoms were reported by the caregiver with the Schizophrenia Outcome Module ( 26 ). In the El Paso sample a trained clinician assessed the symptoms during clinical interviews with the patients by using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ( 27 ).

Caregiver burden was assessed by using the Zarit Burden Scale ( 28 ), which consists of 29 items, each answered on a 3-point scale ranging from 0, not at all true, to 2, extremely true. Zarit and colleagues ( 28 ) conceptualized burden as problems perceived by the caregiver with her or his health, psychological well-being, finances, social life, and the relationship between the caregiver and the ill family member. In the sample presented here internal consistency reliability was good (Cronbach's α =.89).

Stigma was assessed by using an adaptation by Greenberg and colleagues ( 20 ) that was based on the earlier work of Freeman and Simmons ( 29 ). Stigma was measured by using five items rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1, never, to 5, always. These items asked about the extent to which family members avoided having family and friends over or avoided telling others about their child's illness for fear of what others may think of them. In the sample presented here Cronbach's alpha was .84.

Depressive symptoms were assessed by using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale ( 30 ), a measure of the frequency of 20 depressive symptoms that have occurred over the past week, each rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0, rarely, to 3, mostly or all of the time. In the sample presented here Cronbach's alpha was .90.

Results

A majority of primary caregivers were mothers of the ill relative (50 caregivers, or 59%), 14 were spouses (17%), 12 were siblings (14%), five were fathers (6%), and four were other relatives (5%). Three-quarters of the caregivers were of Mexican descent (64 caregivers, or 75%), eight were Puerto Rican (9%), four were Central American (5%), three were South American (4%), two were Cuban (2%), and four did not specify country of origin (5%).

Table 1 shows other characteristics of the caregivers and patients. Caregivers had an average age of 55 years (range of 21 to 81 years). A majority of caregivers were female. Almost half of the caregivers were married and had less than nine years of education. Sixty percent of the caregivers were interviewed in Spanish.

|

The average age of the patients was 39 years (range of 19 to 82). A majority of patients were male. Three-quarters of the patients lived at home with their family caregiver (64 patients, or 75%).

Preliminary and descriptive analyses

We compared the two studies and three study sites on variables used in the analyses and found no significant differences. We also examined differences between Latino ethnicities and whether caregivers were parents, spouses, or siblings. The only significant difference we found was that Central and South Americans had higher levels of education than other Latino groups. The mean burden score for the total sample was 35.0±10.2. The mean CES-D score for this sample was 15.5±11.6. (Possible scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating greater levels of depressive symptoms.) Notably, 34 caregivers (40%) in the study presented here met the standard CES-D cutoff score of 16 or higher, which classifies individuals as having elevated levels of depressive symptoms ( 26 ).

Table 2 shows intercorrelations of study variables. Caregivers' depressive symptoms correlated with caregivers' younger age, lower levels of education, and higher levels of burden and stigma. Patients' male gender and psychiatric symptoms were also related to caregivers' depressive symptoms.

|

Multivariate analyses

Following the stress-process model, stressors (patients' psychiatric symptoms) should be significantly linked with caregivers' depressive symptoms after analyses account for background variables, such as caregivers' demographic characteristics. The first regression model tested this hypothesis ( Table 3 ). Higher levels of patients' psychiatric symptoms were significantly related to higher levels of caregivers' depressive symptoms when we statistically adjusted for caregivers' demographic characteristics. Younger caregiver age and lower caregiver education were significant correlates of depressive symptoms in the multivariate model.

|

We conducted two additional regression models to test the mediating role of burden and stigma separately. According to Baron and Kenny's ( 31 ) mediation criteria, a mediation variable should be significantly associated with both the independent variable (psychiatric symptoms) and the outcome variable (depressive symptoms) and reduce substantially the relation between the independent variable and outcome when introduced in a multivariate analysis. The bivariate results in Table 2 show that psychiatric symptoms, stigma, and burden were all significantly related to depressive symptoms. However, only burden was significantly related to psychiatric symptoms (stigma was not related to psychiatric symptoms). Therefore, only burden met all mediation criteria.

In hierarchical multiple regression analyses, burden and stigma were added to model 1 (symptoms and background variables) to test for the multivariate criterion for mediation ( Table 3 ). Model 2 shows that when burden was added, psychiatric symptoms were no longer significantly related to depressive symptoms. Moreover, the regression coefficient was notably reduced from .22 to .12, suggesting substantial mediation. Figure 1 shows a graphic description of this mediation.

Model 3 shows that when stigma was added, psychiatric symptoms were no longer related to depressive symptoms at the .05 significance level. However, the relation between psychiatric symptoms and depressive symptoms was reduced only from .22 to .18. In this multivariate model, stigma is a significant correlate of depressive symptoms. Thus stigma has an important direct effect on depressive symptoms, but its mediation role in depressive symptoms is questionable at best.

Discussion

Previous research on Latino family caregivers of persons with schizophrenia has been minimal and has primarily focused on how the caregiver's affect toward the patient is related to the course of schizophrenia. Thus little is known about Latino family caregivers' psychological distress related to their caregiving roles. With a sample of Latino (predominantly Mexican-American) family caregivers of adults with schizophrenia, this study used a stress-process model to examine the relation between caregiving stressors (that is, patients' positive psychiatric symptoms) and caregivers' psychological distress, the potential mediating roles of caregivers' appraisals (for example, burden and stigma) in the relation between stressors and psychological distress, and the role of background variables in psychological distress.

Our findings suggest that the mental health of Latino family caregivers is an important focus for research and intervention—40% of the caregivers in the study presented here met the criterion for being at risk of depression (that is, a score of 16 or higher on the CES-D scale). In general population studies of Latinos, between 13% and 18% typically meet this criterion ( 32 ), and in populations of Latino older adults up to 25% meet the criterion ( 23 ). A recent study that focused on Mexican migrant farmworkers in California whose ages were similar to those of participants in our study reported depression rates between 19% and 20% ( 33 ). Thus providing care for an adult with schizophrenia places Latino caregivers at higher risk of depression, compared with the general Latino population.

We found support for our hypothesis that caregivers' subjective burden mediates the relationship between patients' positive symptoms and caregivers' depressive symptoms. This finding is consistent with stress-process models ( 18 , 19 ), which posit that caregivers' appraisals (that is, burden) mediate the association between stressors and psychological distress. Thus more positive symptoms of patients are related to greater feelings of burden among caregivers, which is related to more depressive symptoms. This finding suggests that interventions that work to reduce positive symptoms among patients may indeed reduce the burden and improve the emotional well-being of their caregivers. Second, interventions that focus on how caregivers appraise symptoms (for example, burden related to the illness) may also alleviate psychological distress of caregivers.

We found that stigma was significantly related to caregivers' depressive symptoms independently of other variables. In our study, stigma reflects the extent to which caregivers avoid telling friends and family about the mental illness of their relative. Our study found that stigma was not related to patients' psychiatric symptoms, unlike the findings of other studies ( 20 , 34 ). One explanation of the discrepancy between the findings of the study presented here and other studies may be that researchers in previous studies used measures of psychiatric symptoms that included negative symptoms, whereas we measured only positive symptoms. Negative symptoms may appear to family members as laziness or behaviors that can be controlled by the patient, which may be more stigmatizing to families.

We posited that stigma may be conceptualized as an appraisal variable, such that family caregivers' subjective evaluations of the illness would mediate the relation between levels of patients' symptoms and caregivers' psychological distress. However, we found weak support for the hypothesized mediating role of stigma given that it was weakly related to patients' symptoms, and stigma did not reduce substantially the relation between patients' symptoms and caregivers' distress. Thus, if the case is to be made that stigma has substantial illness appraisal (subjective evaluation) qualities, researchers should examine whether stigma is linked to other illness components, such as negative rather than positive symptoms or perhaps beliefs about mental illness, including attributions of patients' control of their symptoms. Moreover, future research should focus on understanding how stigma is linked to depressive symptoms. For example, Greenberg and colleagues ( 20 ) proposed that greater levels of stigma may have an impact on social support received by the caregiver, because stigma may restrict contact between the caregiver and friends and family.

Other factors associated with depression among caregivers in our study were caregivers' younger age and lower levels of education. Although older age is typically related to higher rates of depression among Latinos ( 23 ), our findings suggest the opposite for family caregivers of persons with schizophrenia. Moreover, our results are consistent with findings in a study of parents of persons with mental illness ( 35 ) and in a study of Latina mothers caring for adults with mental retardation ( 36 ). In both of these studies younger caregivers reported more psychological distress compared with older caregivers. One explanation for the relation between young age and high distress is that younger caregivers, particularly those in midlife, are more likely to have additional major social roles, such as work and other caregiving roles that include raising children and caring for aging parents. Another possibility is that older caregivers may have had more time to develop resources and coping strategies that reduce their levels of psychological distress.

The relationship between lower levels of education among caregivers and higher levels of caregiver depression is consistent with previous research with Latinos ( 22 , 23 ). In the context of caring for an adult with schizophrenia, low levels of education, which are related to lower socioeconomic status, may mean that fewer resources are available to caregivers who are faced with challenging behaviors and other caregiver-related stressors.

One limitation of this study is that the cross-sectional nature of the data do not allow for causal inferences. Second, the samples consisted of volunteer participants who were responsive to announcements and requests to participate by mental health service providers at public outpatient clinics and the research teams who collaborated with the clinics. Thus future researchers should examine the degree to which our findings generalize to patients who are less likely to use public outpatient services and their family caregivers. Third, psychiatric symptoms of the persons with schizophrenia were assessed with two different methods across the study sites. However, the empirical links between symptoms and other variables in this sample that combined both measurement methods were consistent with stress-process models and prior empirical findings ( 19 , 37 ). Moreover, our findings are more likely to underestimate rather than overestimate the relations between symptoms and other variables because measurement error is expected to be higher with our two-method assessment of symptoms than in studies that used only one method.

These limitations notwithstanding, replication of the findings presented here with a uniform measure of psychiatric symptoms and the inclusion of other illness facets, such as negative symptoms, would strengthen the posited implications.

Conclusions

Despite the limitations of this study, the high rates of caregivers' depressive symptoms found in our study suggest that interventions with Latino family caregivers of a relative with schizophrenia should include attention to the mental health of family caregivers in addition to recovery of the patient. Notably, and consistent with past findings ( 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ), three-quarters of the Latino family caregivers lived with the patient. Our findings suggest that current interventions that work with caregivers to help reduce positive psychiatric symptoms of their relative may indeed have an impact on lowering the burden and depression of Latino family caregivers ( 38 ).

However, our data suggest that rather than exclusively targeting patients' symptoms, reducing caregivers' feelings of burden and stigma is also likely to yield significant payoffs in terms of reducing caregivers' psychological distress and thus may be a worthy intervention focus. For example, depression screenings and emotional health assessments could be conducted for caregivers. Interventions could be developed that have a focus on the health and well-being of the caregivers—for example, interventions that focus on stress reduction and health promotion activities. Our results also suggest that researchers and practitioners should attend to the special needs that seem to place caregivers who are relatively young and who have lower levels of education at risk of depression.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by a Minority Supplement awarded to Dr. Magaña from grant R01-MH55928 (Jan Steven Greenberg, Ph.D., principal investigator) from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), by the Paso Del Norte Foundation Center for Border Health Research, and by training grant MH-14584 from NIMH's National Research Service Award, entitled Psychological Research on Schizophrenic Conditions. The authors thank Marvin Karno, M.D., for his input to a draft of the article. The authors thank Alex Kopelowicz, M.D., for assisting with recruitment of participants in Los Angeles; James M. Wood, Ph.D., Larry D. Meyer, M.A., and Bernardo Tarín, M.D., for assistance in recruitment in El Paso; and the many families who gave their valuable time to participate.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Karno M, Jenkins JH, de la Selva A, et al: Expressed emotion and schizophrenic outcome among Mexican-American families. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 175:143–151, 1987Google Scholar

2. Kopelowicz A, Zarate R, López SR, et al: The evaluation of expressed emotion in schizophrenia: a comparison of Caucasians and Mexican-Americans. Schizophrenia Research 55:179–186, 2002Google Scholar

3. Jenkins J, Karno M, de la Selva A, et al: Expressed emotion in cross-cultural context: familial responses to schizophrenic illness among Mexican Americans, in Treatment of Schizophrenia: Family Assessment and Intervention. Edited by Goldstein MJ, Hand I, Hahlweg K. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1986Google Scholar

4. Kopelowicz A, Zarate R, Gonzalez Smith V, et al: Disease management in Latinos with schizophrenia: a family-assisted, skills training approach. Schizophrenia Bulletin 29:211–227, 2003Google Scholar

5. López SR, Hipke KN, Polo JA, et al: Ethnicity, expressed emotion, attributions, and course of schizophrenia: family warmth matters. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 113:428–439, 2004Google Scholar

6. Jenkins JH: Ethnopsychiatric interpretations of schizophrenic illness: the problem of nervios within Mexican-American families. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 12:301–329, 1988Google Scholar

7. Milstein G, Guarnaccia P, Midlarsky E: Ethnic differences in the interpretation of mental illness: perspectives of caregivers. Research in Community and Mental Health 8:155–178, 1995Google Scholar

8. Guarnaccia G, Parra P: Ethnicity, social status, and families' experiences of caring for a mentally ill family member. Community Mental Health Journal 32:243–260, 1996Google Scholar

9. Ramírez García JI, Wood JM, Hosch HM, et al: Predicting psychiatric rehospitalizations: examining the role of Latino versus European American ethnicity. Psychological Services 1:147–157, 2004Google Scholar

10. Biegel D, Milligan S, Putnam P, et al: Predictors of burden among lower socioeconomic status caregivers of persons with chronic mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 30:473–494, 1994Google Scholar

11. Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Krauss MM, et al: The differential effects of social support on the psychological well-being of aging mothers of adults with mental illness or mental retardation. Family Relations 46:383–394, 1997Google Scholar

12. Kim HW, Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, et al: The role of coping in maintaining the psychological well-being of mothers of adults with intellectual disability and mental illness. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 47:313–327, 2003Google Scholar

13. Reinhard SC, Horwitz A: Caregiver burden: differentiating in the content and consequences of family caregiving. Journal of Marriage and the Family 57:741–750, 1995Google Scholar

14. Jenkins JH, Schumacher JG: Family burden of schizophrenia and depressive illness: specifying the effects of ethnicity, gender and social ecology. British Journal of Psychiatry 174:31–38, 1999Google Scholar

15. Struening EL, Stueve A, Vine P, et al: Factors associated with grief and depressive symptoms in caregivers of people with serious mental illness. Research in Community and Mental Health 8:91–94, 1995Google Scholar

16. Stueve A, Vine P, Struening EL: Perceived burden among caregivers of adults with serious mental illness: comparison of black, Hispanic, and white families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:199–209, 1995Google Scholar

17. Magaña S: Aging Latino family caregivers, in The Oxford Handbook of Social Work in Aging. Edited by Berkman B, D'Ambrusco D. New York, Oxford University Press, 2006Google Scholar

18. Lawton M, Kleeban M, Moss M, et al: Measuring caregiving appraisal. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences 44:61–70, 1989Google Scholar

19. Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, et al: Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and measures. Gerontologist 30:583–595, 1990Google Scholar

20. Greenberg JS, Greenley JR, McKee D, et al: Mothers caring for an adult child with schizophrenia: the effects of subjective burden on maternal health. Family Relations 42:205–211, 1993Google Scholar

21. Struening EL, Perlick DA, Link BG, et al: The extent to which caregivers believe most people devalue patients and their families. Psychiatric Services 52:1633–1638, 2001Google Scholar

22. Finch BK, Kolody B, Vega WA: Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 41:295–313, 2000Google Scholar

23. Gonzalez HM, Haan MN, Hinton L: Acculturation and the prevalence of depression in older Mexican Americans: baseline results of the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 49:948–953, 2001Google Scholar

24. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Patient and Bilingual Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0). New York, Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1996Google Scholar

25. Kurtines WM, Szapocznik J: Cultural competence in assessing Hispanic youths and families: challenges in the assessment of treatment needs and treatment evaluation for Hispanic drug abusing adolescents, in Adolescent Drug Abuse: Clinical Assessment and Therapeutic Intervention. Edited by Rahdert E, Czechowicz D. NIDA Research Monograph no 156, Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1995Google Scholar

26. Cuffel B, Fischer E, Owen R, et al: An instrument for measurement of outcomes of care for schizophrenia: issues in development and implementation. Evaluation and the Health Professions 20:96–108, 1997Google Scholar

27. Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J: Manual for the Expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13:261–276, 1986Google Scholar

28. Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J: Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 26:260–266, 1980Google Scholar

29. Freeman HE, Simmons OG: The Mental Patient Comes Home. New York, Wiley, 1963Google Scholar

30. Radloff L: The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1:385–401, 1977Google Scholar

31. Baron RM, Kenny DA: The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51:1173–1182, 1986Google Scholar

32. García M, Marks G: Depressive symptomatology among Mexican-American adults: an examination with CES-D scale. Psychiatry Research 27:137–148, 1989Google Scholar

33. Alderete E, Vega W, Kolody B, et al: Depressive symptomatology: prevalence and psychosocial risk factors among Mexican migrant farmworkers in California. Journal of Community Psychology 27:457–471, 1999Google Scholar

34. Picket S, Greenley J, Greenberg JS: Off-timedness as a contributor to subjective burdens for parents of offspring with severe mental illness. Family Relations 44:195–201, 1995Google Scholar

35. Cook JA: Age and family burden among parents of offspring with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 64:435–447, 1994Google Scholar

36. Magaña S, Smith MJ: Health outcomes of mid-life and aging Latina and black American mothers of children with developmental disabilities. Mental Retardation 44:224–234, 2006Google Scholar

37. Mak WWS: Integrative model of caregiving: how macro and micro factors affect caregivers of adults with server and persistent mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 75:40–53, 2005Google Scholar

38. Dixon L, McFarlene WR, Lefley H, et al: Evidence-based practices for services to families with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 52:903–910, 2001Google Scholar