Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Psychiatric Comorbidity Among Detained Youths

Most youths in detention have one or more psychiatric disorders ( 1 ). Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is one of the more prevalent disorders in detention facilities, affecting at least one in ten youths ( 2 , 3 , 4 ). One of the more debilitating aspects of PTSD is its tendency to co-occur with other psychiatric disorders ( 5 , 6 , 7 ). In a community sample, Giaconia and colleagues ( 8 ) found that nearly four-fifths of persons with lifetime PTSD also had one or more additional psychiatric disorders. Studies of detained adolescent males in Russia ( 9 ) and detained adolescent females in Australia ( 10 ) found that all of the detainees with PTSD had at least one comorbid disorder.

It is unclear whether PTSD increases the vulnerability to other disorders or whether there are common genetic or environmental factors underlying the disorders ( 5 , 11 ). Researchers agree, however, that comorbid disorders have an adverse impact on the prognosis and treatment of individuals with PTSD. Youths with PTSD and comorbid disorders have significantly more behavioral and health problems and more impaired interpersonal relationships than those with PTSD and no comorbid disorders ( 5 ).

Effective treatment planning for detained youths with PTSD requires epidemiological data on patterns of prevalence and comorbidity. Yet to our knowledge no epidemiological study of detainees in the United States has examined PTSD and comorbid psychiatric disorders. In this study we administered standardized diagnostic measures to a large, stratified random sample of detained youths. We compared the prevalence of psychiatric disorders among juvenile detainees with and without PTSD. We also compared the prevalence of PTSD among youths with and without other psychiatric disorders.

Methods

Participants and sampling procedures

Participants were part of the Northwestern Juvenile Project, a longitudinal study of 1,829 youths ten to 18 years of age who were arrested and detained between 1995 and 1998 at the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center in Chicago. The random sample was stratified by sex, race or ethnicity (African American, non-Hispanic white, or Hispanic), age (ten to 13 years or 14 years and older), and legal status (processed as a juvenile or as an adult) to obtain enough participants to examine key subgroups (for example, females, Hispanics, and younger children).

Interviewers described the study to participants and obtained written informed assent if participants were younger than 18 years or consent if they were 18 years or older. The Northwestern University Institutional Review Board, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Institutional Review Board, and the U.S. Office of Protection From Research Risks approved the study and waived parental consent, consistent with federal regulations regarding research with minimal risk. We nevertheless tried to contact parents or guardians to provide them information and offer them an opportunity to decline participation. Despite repeated attempts to contact a parent or guardian, for 44% of the participants, none could be found. In lieu of parental consent, youth assent was overseen by an independent participant advocate representing the interests of the participants. Federal regulations allow for a participant advocate if parental consent is not feasible.

We began collecting data on PTSD 13 months after the larger study began because this was when the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, version IV (DISC-IV) module was available for use. PTSD data were collected for 898 youths. A total of 532 (59%) were male, and 366 (41%) were female. A total of 490 (55%) were African American, 154 (17%) were non-Hispanic white, 252 (28%) were Hispanic, and two (<1%) were of another race or ethnicity. Participants ranged in age from ten to 18 years (mean±SD age, 14.8±1.4 years; median age, 15 years). Additional information on our methods is published elsewhere ( 1 , 2 ).

Measuring PTSD and comorbid disorders

Independent, master's-level clinical research interviewers administered the DISC-IV to assess past-year PTSD by using DSM-IV criteria. The DISC 2.3, the most recent version available when the study began, was used to assess comorbid psychiatric disorders in the past six months based on DSM-III-R criteria. Our data were based on the youths' self-reported data because it was not feasible to interview caretakers. We chose the PTSD module of the DISC-IV because it is the most widely used diagnostic instrument for child and adolescent research ( 12 ); it is relatively brief, it can be administered by nonclinicians, and it is designed to assess youths who have been traumatized and those who have not.

The PTSD module assesses whether youths have ever experienced any of eight traumatic experiences. These include having been in a situation where youths thought they or someone close to them was going to be hurt very badly or die; had been attacked physically or beaten badly; had been threatened with a weapon; were forced to do something sexual that they did not want to do; had been in a bad accident; had been in a fire, flood, tornado, earthquake, or other natural disaster where they thought they were going to die or be seriously injured; had seen or heard someone get hurt very badly or be killed other than on television or in the movies; or had been very upset by seeing a dead body or pictures of a dead body of someone they knew well.

Participants then identify the event that was "the most difficult for you in your entire life." The DISC assesses PTSD diagnosis within the past year for this "worst" trauma. Because the diagnosis of PTSD by the DISC requires that the symptoms last at least one month, PTSD could not have been caused by the stress of the current incarceration.

PTSD could not be determined for four females because of missing data. Other diagnostic information was not available for one female. One male and one female were excluded from analyses because they self-identified as "other" race or ethnicity. All available data from the 891 remaining participants are used for analyses. Of these, 13 participants (seven males, six females) were missing from the category any disorder, six (four males, two females) were missing from the category affective disorder, seven (three males, four females) were missing from the category anxiety disorder, three (one male, two females) were missing from the category attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder or behavioral disorder, 14 (seven males, seven females) were missing from the category any substance use disorder, 14 (five males, nine females) were missing from the category drug use disorder, 14 (six males, eight females) were missing from the category alcohol use disorder, and 27 (11 males, 16 females) were missing from the category both alcohol and drug use disorder.

Because we stratified our sample by sex, race or ethnicity, age, and legal status, we weighted all prevalence estimates to reflect the population of the detention center. All reported inferential tests were corrected for design characteristics with Taylor series linearization by using the survey estimation procedures of Stata SE statistical software, version 9.0. We conducted tests of prevalence rates between groups with logistic regression using an adjusted Wald F statistic.

Results

Prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders

Among the participants with PTSD, 93% had at least one comorbid psychiatric disorder; however, among the participants without PTSD, 64% had at least one comorbid psychiatric disorder (odds ratio [OR]=7.3, 95% confidence interval [CI]=3.2–16.5, p< .001). Among participants with PTSD, 54% had two or more types of comorbid disorders—that is, affective, anxiety, behavioral, or substance use disorder—and 11% had all four types of comorbid disorders.

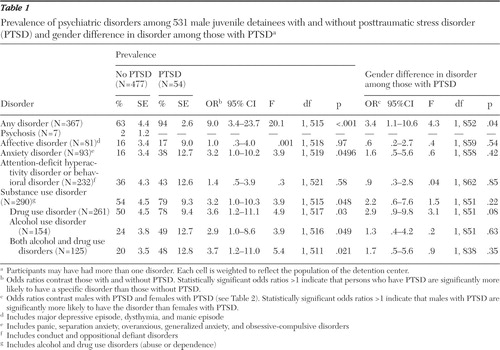

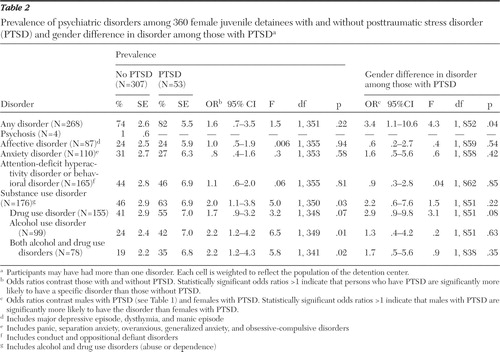

Tables 1 and 2 show the prevalence and odds ratios of psychiatric disorders among participants with and without PTSD. Males with PTSD had significantly greater odds than males without PTSD of having any comorbid psychiatric disorder, anxiety disorder, and drug use disorder ( Table 1 ). Both males and females with PTSD had significantly greater odds of having any substance use disorder, alcohol use disorder, and both alcohol and drug use disorders than those without PTSD ( Tables 1 and 2 ). Having PTSD did not significantly increase the odds of having an affective or behavioral disorder for either males or females. The prevalence of any comorbid psychiatric disorder was significantly greater for males with PTSD than that for females with PTSD (OR=3.4, CI=1.1–10.6, p<.05) ( Tables 1 and 2 ).

|

|

Prevalence of PTSD

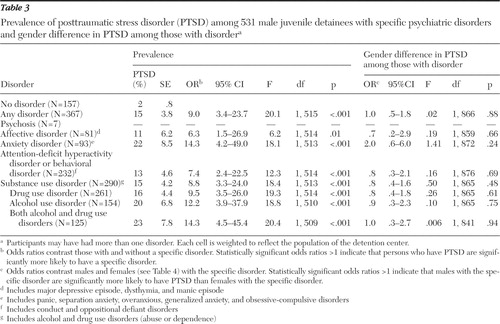

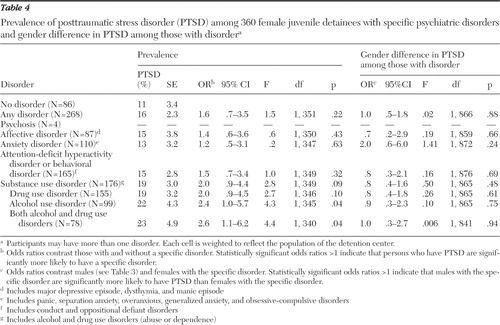

Table 3 shows that among males, having any psychiatric diagnosis, including any affective, anxiety, behavioral, or substance use disorders, significantly increased the odds of having comorbid PTSD, compared with those with no other psychiatric disorder. Among females, only alcohol use disorder and both alcohol and drug use disorders significantly increased the odds of having PTSD ( Table 4 ). No significant difference in prevalence rates of PTSD was found between males and females with specific psychiatric disorders ( Tables 3 and 4 ).

|

|

Discussion

Juvenile detainees with PTSD almost invariably have a comorbid disorder. In this study over half had two or more types of comorbid disorders. The prevalence rate of drug use disorder—the most common comorbid disorder among youths with PTSD—is two to three times higher than rates of drug dependence found in a sample of high school seniors with PTSD ( 8 ). Rates of PTSD among the detainees with substance use disorders in this study are also similar to or higher than rates among youths with substance use disorders receiving psychiatric or substance use treatment ( 13 , 14 ).

Although comorbidity is a significant problem for both male and female detainees with PTSD, males were more likely to have comorbid disorders than females. Similar findings were reported among adults in the National Comorbidity Survey ( 15 ); however, the opposite pattern was reported in a sample of chemically dependent adolescents ( 13 ). This gender difference warrants further study.

Our findings may pertain only to youths in urban detention centers with similar demographic composition. Because it was not feasible to interview caretakers, our data are subject to the reliability and validity of youths' self-report; however, youths and their caretakers have been found to provide comparable reports of youths' anxiety disorders ( 16 ). The DISC-IV—like most measures of PTSD—uses the single-worst trauma as the stem question; hence, we were unable to estimate the age at onset of PTSD. Finally, our rates might differ somewhat if we had been able to use DSM-IV instead of DSM-III-R criteria to measure comorbid disorders.

Conclusions

Our findings have implications for the treatment of PTSD among at-risk youths. First, detection of comorbid PTSD among detained youths must be improved. PTSD is often missed, even in psychiatric settings ( 17 ), because traumatic experiences are rarely included in standard screens or volunteered by patients ( 6 ). Screening should also determine the relative onset of disorders, which may indicate which disorder should be the primary target for treatment.

Second, the treatment ramifications of comorbid disorders should be considered. Even brief psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions for detainees with PTSD must address comorbid disorders, especially substance use disorders. Detoxification or withdrawal from substances can worsen the symptoms of PTSD ( 6 ). Exploration of traumatic experiences—a common psychotherapeutic tool for treatment of PTSD—may worsen symptoms of comorbid mood disorders or precipitate self-medication and relapse for those in recovery ( 6 ). Medication management requires special attention to potential for abuse and drug interactions ( 7 , 18 ). Finally, the high-risk behaviors associated with certain psychiatric disorders, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, mania, and substance use disorder ( 13 , 19 ), may increase the likelihood of experiencing additional traumas.

Juvenile detainees typically remain in facilities for only two weeks before release ( 20 ). Hence, their mental health needs must be addressed by community psychiatry as well as correctional service systems. The treatments most likely to succeed will address past traumas and the diagnostic complications that often follow.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grants R01-MH-54197 and R01-MH-59463 from the Division of Services and Intervention Research and Center for Mental Health Research on AIDS, National Institute of Mental Health, and by grants 1999-JE-FX-1001 and 2005-JL-FX-0288 from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Major funding was also provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Center for Mental Health Services, Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, and Center for Substance Abuse Treatment), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (National Center on Injury Prevention and Control and National Center for HIV, STD and TB Prevention), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Research on Women's Health, the NIH Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the NIH Office on Rare Diseases, the Department of Labor, the William T. Grant Foundation, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Additional funds were provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Open Society Institute, and the Chicago Community Trust. The authors thank these agencies for their collaborative spirit and steadfast support. This study could not have been accomplished without the advice of Ann Hohmann, Ph.D., Kimberly Hoagwood, Ph.D., Heather Ringeisen, Ph.D., Grayson Norquist, M.D., and Delores Parron, Ph.D. Celia Fisher, Ph.D., guided human subject procedures.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, et al: Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:1133–1143, 2002Google Scholar

2. Abram KM, Teplin LA, Charles DR, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:403–410, 2004Google Scholar

3. Cauffman E, Feldman S, Waterman J, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder among female juvenile offenders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 37:1209–1216, 1998Google Scholar

4. Steiner H, Garcia IG, Matthews Z: Posttraumatic stress disorder in incarcerated juvenile delinquents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:357–365, 1997Google Scholar

5. Giaconia RM, Reinherz HZ, Hauf AC, et al: Comorbidity of substance use and post-traumatic stress disorders in a community sample of adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 70:253–262, 2000Google Scholar

6. Brady KT: Posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbidity: recognizing the many faces of PTSD. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58:12–15, 1997Google Scholar

7. Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR: Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the literature. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:1184–1190, 2001Google Scholar

8. Giaconia RM, Reinherz HZ, Silverman AB, et al: Traumas and posttraumatic stress disorder in a community population of older adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 34:1369–1380, 1995Google Scholar

9. Ruchkin VV, Schwab-Stone M, Koposov R, et al: Violence exposure, posttraumatic stress, and personality in juvenile delinquents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 41:322–329, 2002Google Scholar

10. Dixon A, Howie P, Starling J: Trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress, and psychiatric comorbidity in female juvenile offenders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 44:798–806, 2005Google Scholar

11. Breslau N, Davis GC, Peterson EL, et al: A second look at comorbidity in victims of trauma: the posttraumatic stress disorder– major depression connection. Biological Psychiatry 48:902–909, 2000Google Scholar

12. Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas C: The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC), in Comprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment, Vol 2. Edited by Hilsenroth MJ, Segal DL. Hoboken, NJ, Wiley, 2003Google Scholar

13. Deykin EY, Buka SL: Prevalence and risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder among chemically dependent adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:752–757, 1997Google Scholar

14. Garland AF, Hough RL, McCabe KM, et al: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in youths across five sectors of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 40:409–418, 2001Google Scholar

15. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:1048–1060, 1995Google Scholar

16. Jensen PS, Rubio-Stipec M, Canino G, et al: Parent and child contributions to diagnosis of mental disorder: are both informants always necessary? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:1569–1579, 1999Google Scholar

17. Mueser KT, Goodman LB, Trumbetta SL, et al: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:493–499, 1998Google Scholar

18. Arroyo W: PTSD in children and adolescents in the juvenile justice system, in PTSD in Children and Adolescents. Edited by Eth S. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2001Google Scholar

19. Wozniak J, Crawford MH, Biederman J, et al: Antecedents and complications of trauma in boys with ADHD: findings from a longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:48–56, 1999Google Scholar

20. Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, et al: Detecting mental disorder in juvenile detainees: who receives services? American Journal of Public Health 95:1773–1780, 2005Google Scholar