Risk of Psychological Difficulties Among Children Raised by Custodial Grandparents

Although increasing numbers of grandparents are becoming surrogate parents to grandchildren ( 1 ), little is known about how custodial grandchildren fare in these families. Yet there are two major reasons why custodial grandchildren may encounter greater risk of behavioral and emotional difficulties than children in general. One reason is that custodial grandchildren typically receive care from grandparents because of such predicaments among their parents as substance abuse, child abuse and neglect, teenage pregnancy, death, illness, divorce, incarceration, and HIV-AIDS ( 2 ). Such predicaments bear numerous risks of psychopathology among custodial grandchildren, including exposure to prenatal toxins, early childhood trauma, insufficient interaction with parents, family conflict, uncertainty about the future, and societal stigma ( 3 , 4 ).

Another reason why custodial grandchildren may experience higher risk of emotional and behavioral difficulties concerns the numerous challenges that grandparents face as caregivers. For many this role is developmentally off time, unplanned, ambiguous, and undertaken with considerable ambivalence ( 5 , 6 , 7 ). Additional challenges to raising custodial grandchildren include inadequate support, social stigma, isolation, disrupted leisure and retirement plans, age-related adversities, anger toward grandchildren's parents, and financial strain ( 8 , 9 , 10 ). Thus custodial grandparents typically show elevated rates of anxiety, irritability, anger, and guilt ( 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ). Such heightened psychological strain among parental figures is troubling because abundant research shows that psychological distress is associated with increased dysfunctional parenting, which, in turn, negatively affects children's psychological well-being ( 16 ). Recently, it was found that psychological distress among custodial grandmothers results in lower-quality parenting, which ultimately leads to higher maladjustment of custodial grandchildren ( 17 ).

Despite these speculations that custodial grandchildren may experience greater mental health difficulties than children in general, scant research has examined the well-being of custodial grandchildren in comparison with other children. A handful of studies, however, provide preliminary evidence that custodial grandchildren do face higher risk. For instance, Ghuman and colleagues ( 18 ) found that 22% of 233 youths attending an inner-city community mental health center for treatment of psychological difficulties were cared for by grandparents. Although this rate was disproportionately higher than the 6% of all children living in a grandparent's household ( 19 ), generalizability of these findings is unknown because the sample was restricted to custodial grandchildren from a single clinic.

Further evidence of increased risk of psychological difficulties among custodial grandchildren comes from studies of children who receive kinship care. Dubowitz and colleagues ( 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ) reported studies showing that children under kinship care have more behavioral, emotional, and school-related problems than children in general. Billing and colleagues ( 24 ) analyzed data from the 1997 and 1999 rounds of the National Survey of America's Families and found that children under age 18 living with relatives fared worse than children living with biological parents on most measures of behavioral, emotional, and physical well-being. They also found that children in care of relatives were more likely to have caregivers with symptoms of poor mental health themselves.

Using a nationally representative sample of middle-school children from the 1988 National Education Longitudinal Study, Sun ( 25 ) compared the educational, psychological, and behavioral outcomes of children in non-biological-parent families with outcomes of children in households containing two biological parents, a single mother, a stepmother, or a stepfather. According to Sun, non-biological-parent households were found to provide a less favorable family environment for children to live in, as shown by the shortage of parental functions and resources in these households that were associated with lower levels of well-being among children.

Because none of the studies reviewed above differentiated children raised by grandparents from children raised by other relatives, the applicability of their findings in regard to custodial grandchildren remains unknown. In the only published national study focused on custodial grandchildren, Solomon and Marx ( 26 ) used secondary data from the 1988 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) to address how custodial grandchildren compare with children from traditional and other types of alternative family (single-parent and blended families) on health and school-adjustment indicators. Caregivers were asked about their perceptions of children in their care. Children from traditional nuclear families were perceived as being better students and less likely to repeat a grade compared with custodial grandchildren, whereas children raised in families with one biological parent did not perform any better on these indicators than custodial grandchildren.

Children from traditional families were not better behaved at school than custodial grandchildren, and children from families with one biological parent were more likely than custodial grandchildren to experience school-related behavioral problems. Solomon and Marx also examined indices of physical health status and found that custodial grandchildren fared quite well relative to children in all other family structures. On the basis of overall findings, the authors concluded that "children being raised solely by grandparents appear to be relatively healthy and well-adjusted." However, a major limitation of their investigation is that an established measure of children's psychological adjustment was unavailable in the 1988 NHIS data set.

The study

Our study is the first to examine risk of emotional and behavioral difficulties among custodial grandchildren from a large, national data set and uses a well-established measure of psychological adjustment. We asked a national sample of 366 black and 367 white custodial grandmothers to complete the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) ( 27 ) in regard to a target grandchild. The SDQ is a psychometrically sound measure of the psychological adjustment of children that correlates substantially with similar instruments like the Rutter ( 28 ) and Achenbach ( 29 ) questionnaires ( 27 , 30 ), differentiates children with and without psychopathology ( 27 , 31 , 32 ), and effectively screens for disorders in community samples ( 32 ).

Because SDQ normative data from a probability-based sample of U.S. children between ages four and 17 within the 2001 NHIS were readily available, we used these data to address the following aims regarding the extent to which custodial grandchildren are at risk of psychological difficulties.

First, we sought to compare the sample of custodial grandchildren with the normative sample from the 2001 NHIS. Given the above evidence, we hypothesized that grandmothers would report significantly higher behavioral and emotional difficulties among custodial grandchildren than caregivers of children in the NHIS sample. We further hypothesized that custodial grandchildren of both genders would have more difficulties than their NHIS counterparts, given that the above risk factors encountered by custodial grandchildren are not gender specific. However, we predicted that male custodial grandchildren would have significantly higher difficulties than female custodial grandchildren in view of past findings that boys in kinship care demonstrate greater behavioral disturbance than girls ( 21 , 26 ).

Second, we sought to examine whether custodial grandchildren of grandmothers recruited by population-based or convenience methods differed from each other and whether both subgroups differed from the NHIS sample. These comparisons were important given concerns within the family caregiving literature that convenience samples are biased toward greater psychological distress ( 33 ). Our study was a unique attempt to examine this concern empirically.

Our third aim was to determine whether race differences existed within the sample of custodial grandchildren. Exploring potential race differences was important because white and black grandchildren were disproportionately sampled in our study, whereas race was sampled in proportion to the U.S. population within the NHIS. Thus any racial differences in the custodial grandchildren sample might compromise comparisons with the NHIS sample. It is also possible that ethnic and cultural differences exist in how caregivers perceive their children and what they report on instruments such as the SDQ ( 34 ).

Our fourth aim was to classify the custodial grandchildren sample into low-, medium-, or high-difficulties groups with the SDQ banded-scoring procedure ( 27 , 35 ) and to compare these banded scores with those of the NHIS sample. This aim was important because SDQ banded scores in the high-difficulties range are useful in identifying caseness, or children with significant emotional or behavioral difficulties ( 27 , 35 , 36 ). Goodman ( 27 ) favors banded scores over standard cutoff scores because caseness may not have identical meaning across different samples simply because the same cutoffs have been used. Thus comparability may be lost when high- and low-risk samples are contrasted on standard cutoff scores.

Methods

Study data came from two sources. Data on custodial grandchildren were from 733 grandmothers (mean±SD age=56±8.1 years) recruited from 48 states through convenience methods (N=387) and population-based methods (N=346) for a study of stress and coping among custodial grandparents.

Population-based sampling involved a randomized mail recruitment strategy where U.S. households with children of ages zero to 18 years were sent recruitment letters requesting contact with project staff if the household contained—or if a household member knew of—a grandmother meeting study eligibility criteria (providing full-time care for at least three consecutive months to custodial grandchildren between ages four and 17 with both biological parents absent). Lists of randomly selected households containing children between ages zero and 18 were purchased from Survey Sampling, Inc. By asking if the randomly selected household knew of a custodial grandmother, if one was not present in that household, we followed the recommended "counting rule" procedure for obtaining population-based samples of rare populations ( 37 ). Convenience sampling involved appeals to community organizations, churches, social service agencies, and mass media announcements. Prospective respondents were screened, and those meeting study criteria participated in telephone interviews (from March 2003 to January 2004) that included completing the SDQ in reference to a target grandchild for the study.

A description of the study was read to respondents before informed consent was obtained verbally in compliance with the university's institutional review board. If respondents cared for multiple grandchildren, the target grandchild was selected by the most-recent-birthday technique ( 38 ). Target grandchildren were 391 girls and 342 boys (age=9.8±3.7 years). Length of care ranged from three months to 16 years (6.4±4.0 years).

Data regarding the NHIS 2001 sample of U.S. children between ages four and 17 were obtained from www.sdqinfo.com. The SDQ was included in the 2001 NHIS supplement. The NHIS is a multistage probability sample survey on the health of the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau via face-to-face interviews. Information about one randomly selected child in a household was obtained from an adult with knowledge of the child's health. Of the 10,367 children between ages four and 17 in the NHIS survey, 9,878 (95%) children had complete SDQ data, and this sample was used in our analyses. Approximately 92% of reporters were the child's parents. Although a grandparent was the reporter for 4.4% of the sample, separate data were not available by reporter type. The NHIS SDQ data were recently proclaimed as "the best available resource for characterizing youths with serious emotional disturbances" ( 36 ).

The SDQ contains 25 items divided equally among five scales: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity and inattention, peer problems, and prosocial behavior. Reporters rate each item concerning the target child along a 3-point scale that ranges from 0, not true, to 2, certainly true. A total difficulties score is obtainable by summing all subscale scores except for the score for prosocial behavior. Full SDQ scoring procedures are available at www.sdqinfo.com. Banded scores can be computed when cumulative frequency distributions are used to divide the scores for the SDQ total difficulties scale and each subscale into three bands: the highest 10% of scores represents the high-difficulties group, the next 10% is the medium-difficulties group, and the remaining 80% is the low-difficulties group (banding is reversed for the prosocial subscale). Key psychometric properties of the SDQ were previously found to be acceptable for both the NHIS sample ( 35 ) and the custodial grandchildren sample ( 39 ).

Mean comparisons of the custodial grandchildren sample with the NHIS sample were performed with Welch's unpaired t-test procedure as computed online with GraphPad Software (www.graphpad.com). Mean comparisons between subgroups of the custodial grandchildren sample were made with the independent samples t-test procedure of SPSS 12.0 for Windows ( 40 ). Standardized effect size (mean difference divided by pooled standard deviation) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for all mean comparisons.

Results

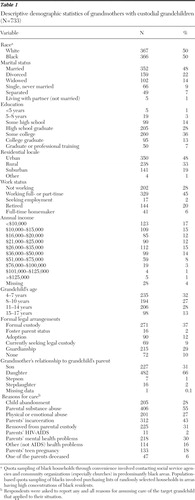

By design, half of the grandmothers were black (N=366) and half were white (N=367), and the sample was diverse along key sociodemographic characteristics ( Table 1 ). Most grandmothers reported multiple reasons for raising the target grandchild, which primarily concerned predicaments of that child's parents.

|

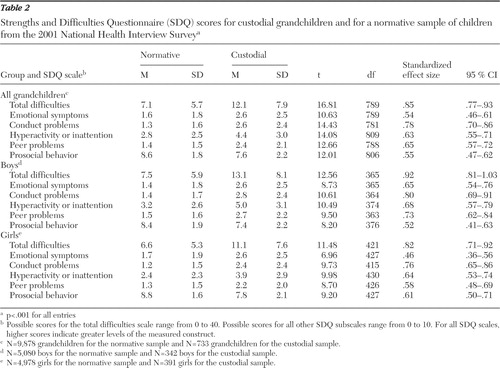

Comparisons of SDQ scores for custodial grandchildren with scores for children in the NHIS sample are summarized in Table 2 . Regardless of the child's gender, grandmothers reported greater difficulties than did caregivers from the NHIS sample across all SDQ scales. Each of the mean differences were not only highly significant (p<.001), but the magnitude of these effects was large.

|

Table 3 summarizes SDQ scores according to gender of custodial grandchildren and race of grandmothers with data from only the custodial grandchildren sample. [An expanded table showing full t test data and corresponding degrees of freedom is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org.] In terms of gender, grandmothers reported boys to present significantly more difficulties than girls on every scale except for emotional symptoms. The corresponding standardized effect sizes are small (.00–.37). As for race, white grandmothers reported significantly more difficulties with custodial grandchildren than did black grandmothers on each subscale except conduct problems and prosocial behavior. The standardized effect sizes associated with these statistically significant differences were small (.14–.25).

|

A summary of mean comparisons by recruitment source is presented in Table 4 . [An expanded table showing full t test data and corresponding degrees of freedom is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org.] The custodial grandchildren were reported as having more difficulties than the NHIS children on all SDQ scales regardless of whether grandmothers were recruited via population-based or convenience methods. However, both the t-score values and corresponding effect sizes were somewhat larger for comparisons between the custodial grandchildren convenience sample and the NHIS sample than for comparisons between the custodial grandchild population-based sample and NHIS sample. In turn, in a direct comparison of the convenience sample and population-based sample of custodial grandchildren, grandmothers recruited by convenience reported significantly more difficulties across all SDQ subscales except for emotional symptoms and prosocial behavior.

|

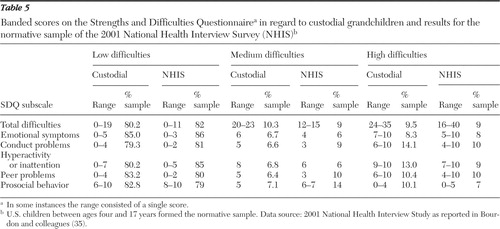

Table 5 contains a summary of banded scores computed separately for the 2001 NHIS sample by Bourdon and colleagues ( 35 ) and for the custodial grandchildren sample. Cutoff scores for both the medium- and high-difficulties classifications were uniformly higher for custodial grandchildren than for NHIS children across all SDQ scales.

|

Discussion

Our findings provide new evidence that custodial grandchildren of both genders are at greater risk of psychological difficulties than children in the general population. Statistically significant mean differences with correspondingly large effect sizes were observed between the custodial grandchildren and NHIS samples on each domain measured by the SDQ. These differences, all in the direction of greater risk of psychological difficulties among custodial grandchildren, occurred regardless of whether comparisons to the NHIS sample involved data from grandmothers recruited through convenience or population-based methods. Nevertheless, consistent with the belief that samples obtained by convenience are biased toward greater psychological distress ( 33 ), grandmothers sampled by convenience reported significantly more difficulty for custodial grandchildren than did grandmothers recruited via population-based sampling on most SDQ scales. Thus samples recruited solely by convenience are likely to overestimate the extent of psychological difficulties in the population of custodial grandchildren.

As anticipated, grandmothers reported more difficulties for boys than for girls except for the emotional symptoms subscale. Absence of gender differences on this subscale, however, may be attributable to the inability of lay observers to recognize symptoms of internalizing disorders ( 34 ). In general, our results are congruent with those of past studies showing that among children in kinship care, boys experience greater behavioral problems and less prosocial behavior than girls ( 21 , 26 , 41 ).

It is noteworthy that the magnitude of the differences observed on the SDQ scales between the NHIS and custodial grandchildren samples was consistently higher than the corresponding differences observed for the within-sample comparisons (that is, population-based versus convenience, boys compared with girls, and white-black racial comparisons) involving the custodial grandchildren sample only. Thus it appears that the power to detect differences between custodial grandchildren and noncustodial grandchildren is much greater than the power to detect differences between subgroups of custodial grandchildren. This trend became evident, for example, by the complete absence of differences found between white grandchildren and black grandchildren on the conduct disorder and prosocial behavior scales.

The finding that white custodial grandmothers reported more difficulties with custodial grandchildren than black grandmothers on some but not all SDQ subscales (emotional, hyperactivity, and peer) is similar to Pruchno's ( 42 ) findings where differences between black and white custodial grandmothers depended on the specific behavior problems under consideration. Whereas white grandmothers in Pruchno's national sample were more likely to report a grandchild as argumentative, impulsive, unhappy, withdrawn, too dependent on others, feeling worthless, or acting too young for one's age, black grandmothers more often reported that custodial grandchildren had lied or cheated, were disobedient at school, destroyed things, and got into fights. Future research is needed to decipher why black and white custodial grandmothers report different patterns of behavioral and emotional problems of their custodial grandchildren.

Our findings regarding the comparison of custodial grandchildren's banded SDQ scores with those for the NHIS sample indicate that substantially more custodial grandchildren would have fallen into the high-difficulties category if cutoff points associated with the NHIS sample had been used instead of calculating sample-specific cutoff points. In fact, across all three scoring bands, cutoff points were lower for the NHIS sample on each SDQ subscale than for the custodial grandchildren sample. These results, along with the higher mean scores observed for custodial grandchildren, indicate that custodial grandmothers judged custodial grandchildren much more negatively than did caregivers of children in the general population. This finding is critical because a caregiver's judgment of the severity of a child's difficulties is key to bringing the child's problems to the attention of mental health providers and to pursuing services for the child ( 35 ). In this respect our findings are consistent with Ghuman and colleagues' ( 18 ) observation that custodial grandchildren are likely to have elevated mental health symptoms in need of professional intervention.

Several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. First, it is unlikely that the SDQ identifies emotionally disturbed youths with the same precision as more extensive interview and diagnostic procedures ( 36 ). This is especially true when parent figures are the sole reporters, given that their own psychological distress is likely to bias their observations ( 34 ). Second, our SDQ data differed from those of the NHIS in some ways that might have affected the findings. For example, we used the British English version of the SDQ, whereas the NHIS used a modified Americanized version. We used telephone interviews, whereas the NHIS conducted face-to-face interviews. Also, the NHIS data encompass a representative sample of all races, whereas our data are from only black and white participants. Third, despite population-based sampling, our sample of custodial grandmothers was relatively small and not necessarily representative of the underlying population of custodial grandparents given that no comprehensive sampling frame exists for this rare population ( 43 ). Finally, we do not know how long any difficulties reported for children in either the NHIS or custodial grandchildren samples had been present.

Conclusions

Despite limitations, our findings suggest that custodial grandchildren are at greater risk of mental health problems than children in general. Given the dearth of research on the well-being of custodial grandchildren, we hope that this study will draw further attention to the needs of custodial grandchildren and their caregivers. Additional research is needed to determine the rates of specific diagnosable disorders experienced by custodial grandchildren, the underlying reasons for these disorders, and whether they vary by key sociodemographic and cultural influences.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Work on this study was funded by grant R01-MH-66851-02 from the National Institute of Mental Health, awarded to the first author.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Simmons T, Dye JL: Grandparents Living With Grandchildren: 2000. October 2003. Available at www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/c2kbr-31.pdfGoogle Scholar

2. Pinson-Milburn NM, Fabian ES, Schlossberg NK, et al: Grandparents raising grandchildren. Journal of Counseling and Development 74:548–554, 1996Google Scholar

3. Hayslip B, Shore RJ, Henderson CE, et al: Custodial grandparenting and the impact of grandchildren with problems on role satisfaction and role meaning. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences 53B:S164–S173, 1998Google Scholar

4. Hirshon BA: Grandparents as caregivers, in Handbook of Grandparenthood. Edited by Szinovacz ME. Westport, Conn, Greenwood Press, 1998Google Scholar

5. Edwards OW: Helping grandkin-grandchildren raised by grandparents: expanding psychology in the schools. Psychology in the Schools 35:173–181, 1998Google Scholar

6. Landry-Meyer L, Newman BM: An exploration of the grandparent caregiver role. Journal of Family Issues 25:1005–1025, 2004Google Scholar

7. Weber JA, Waldrop DP: Grandparents raising grandchildren: families in transition. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 33:27–46, 2000Google Scholar

8. Daly SL, Glenwick DS: Personal adjustment and perceptions of grandchild behavior in custodial grandmothers. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 29:108–118, 2000Google Scholar

9. Glass JC: Grandparents parenting grandchildren: extent of situation, issues involved, and educational implications. Educational Gerontology 28:139–161, 2002Google Scholar

10. Whitley DM, Kelley SJ, Sipe TA: Grandmothers raising grandchildren: are they at increased risk of health problems? Health and Social Work 26:105–114, 2001Google Scholar

11. Burnette D: Physical and emotional well-being of custodial grandparents in Latino families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 69:305–318, 1999Google Scholar

12. Kelly SJ: Caregiver stress in grandparents raising grandchildren. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship 25:331–337, 1993Google Scholar

13. Minkler M, Fuller-Thomson E, Miller D, et al: Depression in grandparents raising grandchildren: results of a national longitudinal study. Archives of Family Medicine 6:445–452, 1997Google Scholar

14. Szinovacz ME, DeViney S, Atkinson MP: Effects of surrogate parenting on grandparents' well-being. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences 54B:S376–S388, 1999Google Scholar

15. Strawbridge W, Wallhagen M, Shema S, et al: New burdens or more of the same? Comparing adult grandparent, spouse, and adult-child caregivers. Gerontologist 17:505–510, 1997Google Scholar

16. Elgar FJ, McGrath PJ, Waschbusch DA, et al: Mutual influences on maternal depression and child adjustment problems. Clinical Psychology Review 24:441–459, 2004Google Scholar

17. Smith GC, Richardson RA, Palmieri PA: The effects of custodial grandmothers' psychological distress on parenting behavior and grandchild behavioral problems. Presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Gerontological Society of America, Dallas, Nov 16–20, 2006Google Scholar

18. Ghuman HS, Weist MD, Shafer ME: Demographic and clinical characteristics of emotionally disturbed children being raised by grandparents. Psychiatric Services 50:1496–1498, 1999Google Scholar

19. Lugaila T, Overturf J: Children and the Households They Live in: 2000. Available at www.census.gov/prod/2004pubs/censr-14.pdf, 2004Google Scholar

20. Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Zuravin S et al: The physical health of children in kinship care. American Journal of Diseases of Children 146:603–610, 1992Google Scholar

21. Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Harrington D, et al: Children in kinship care: how do they fare? Children and Youth Services Review 16:85–106, 1994Google Scholar

22. Dubowitz H, Sawyer RJ: School behavior of children in kinship care. Child Abuse and Neglect 18:899–911, 1994Google Scholar

23. Sawyer RJ, Dubowitz H: School performance of children in kinship care. Child Abuse and Neglect 18:587–597, 1994Google Scholar

24. Billing A, Ehrle J, Kortenkamp K: Children Cared for by Relatives: What Do We Know About Their Well-Being? Washington, DC, Urban Institute, Assessing the New Federalism Project, 2002Google Scholar

25. Sun Y: The well-being of adolescents in households with no biological parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family 65:894–909, 2003Google Scholar

26. Solomon JC, Marx J: "To grandmother's house we go": health and school adjustment of children raised solely by grandparents. Gerontologist 35:386–394, 1995Google Scholar

27. Goodman R: The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 38:581–586, 1997Google Scholar

28. Rutter MA: Children's behaviour questionnaire for completion by teachers: preliminary findings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 8:1–11, 1967Google Scholar

29. Achenbach TM: Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1991Google Scholar

30. Goodman R: The extended version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 40:791–801, 1999Google Scholar

31. Goodman R: Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 40:1337–1345, 2001Google Scholar

32. Goodman R, Ford T, Simmons H, et al: Using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) to screen for child psychiatric disorders in a community sample. British Journal of Psychiatry 177:534–539, 2000Google Scholar

33. Picot SJF, Samonte J, Tierney JA, et al: Effective sampling of rare population elements. Research on Aging 23:694–712, 2001Google Scholar

34. Simpson GA, Bloom B, Cohen RA, et al: US Children With Emotional and Behavioral Difficulties: Data From the 2001, 2002, and 2003 National Health Interview Surveys, Advance Data From Vital and Health Statistics. No 360. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, 2005Google Scholar

35. Bourdon KH, Goodman R, Rae D, et al: The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: US normative data and psychometric properties. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 44:557–564, 2005Google Scholar

36. Mark TL, Buck JA: Characteristics of US youths with serious emotional disturbance: data from the National Health Interview Survey. Psychiatric Services 57:1573–1578, 2006Google Scholar

37. Blair J: Improving data quality in network surveys of rare populations, in Data Quality Control: Theory and Pragmatics. Edited by Liepins GE, Uppuluri VR. New York, Marcel Dekker, 1990Google Scholar

38. Kish L: Survey Sampling. New York, Wiley, 1965Google Scholar

39. Palmieri PA, Smith GC: Examining the structural validity of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) in a US sample of custodial grandmothers. Psychological Assessment 19:189–198, 2007Google Scholar

40. George D, Mallery P: SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference 12.0 Update, 5th ed. Boston, Allyn & Bacon, 2005Google Scholar

41. Dunn J, Deater-Deckard K, Pickering K, et al: Children's adjustment and prosocial behaviour in step-, single-parent, and non-stepfamily settings: findings from a community study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 39:1083–1095, 1998Google Scholar

42. Pruchno RA: Raising grandchildren: the experience of Black and White grandmothers. Gerontologist 39:209–221, 1999Google Scholar

43. Smith GC, Kohn SJ, Trepal H: The effects of sampling strategies on family caregiving research: the case of custodial grandmothers. Presented at the 57th annual scientific meeting of the Gerontological Society of America, Washington, DC, Nov 19–23, 2004Google Scholar