Changes in the Quality of Care for Bipolar I Disorder During the 1990s

Bipolar disorder is chronic, recurring, disabling ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ), and often deadly ( 5 , 6 ). It is estimated to have higher direct health care costs per person than diabetes, other general medical conditions, and major depression ( 7 ), as well as all other psychiatric illness in a privately insured population ( 8 ). Also, departures from evidenced-based treatment—such as delaying or not providing medications like lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine—have been associated with higher health care costs ( 9 ).

Despite the significant personal, economic, and social consequences of bipolar disorder, the existing literature raises quality concerns ranging from accurate diagnosis ( 10 ) to appropriate pharmacotherapy ( 9 , 11 , 12 ) and adequate monitoring of lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine ( 13 , 14 ).

Beginning in the 1990s the development of new pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy has improved the potential to effectively treat bipolar disorder. Treatment guidelines have reflected this growing evidence base. Concurrently, the 1990s saw an increase in the influence of managed behavioral health carve-outs on service delivery. As a result, carve-outs can exert great pressure on the type and amount of treatments patients receive. The literature is clear that managed care controls costs ( 15 ); less clear is its effect on quality ( 16 ).

The combination of emerging treatment technologies, promulgation of guidelines, and major changes in mental health service delivery and resource allocation highlight the importance of examining the way the quality of usual care for bipolar disorder changes over time. A small body of literature has examined the net impact on quality of these changing technologies in the face of changing insurance organization. The purpose of this study was to examine whether there were changes in the quality of bipolar I disorder treatment between 1991 and 1999.

Methods

Data

We used a Medstat data set that included administrative data from a large privately insured population for the years 1991, 1994, and 1999. The Medstat data set contains outpatient, inpatient, and pharmacy claims for enrollees who were the employees, spouses, and dependents from four large U.S. employers. In 1991 and 1994 the enrollee population consisted of approximately 400,000 enrollees who were located in the Midwest section of the United States. The 1999 enrollee population was larger and consisted of approximately 2.3 million people from four large employers (two of whom were different from the earlier year samples) and was located in a more geographically diverse area of the United States. Because of the geographical distribution differences in the 1999 sample, we matched persons in 1999 with persons in 1994 by region once the bipolar I cohort was determined.

Over the study years there was evidence in the Medstat data of an increase in the penetration of managed care. Additionally, by 1995 approximately half of the enrollees' mental health care or substance use disorder treatment was managed by behavioral health carve-outs.

Establishing the bipolar cohort

Unützer and colleagues ( 17 ) compared diagnoses of bipolar disorder on the basis of claims data with chart reviews in a large staff-model health maintenance organization. They were able to confirm the diagnosis of bipolar I or II disorder by chart review in approximately 94 percent of the cases sampled. We used a similar but more stringent claims-based algorithm. We excluded enrollees with an ICD-9 diagnosis of schizophrenia in at least two claims. We required a confirmatory claim for the ICD-9 diagnosis of bipolar disorder unless the nonconfirmed bipolar diagnosis claim represented either one of two things. One, an inpatient claim with a discharge diagnosis of bipolar disorder in the absence of any inpatient claims with a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenia. Or two, an outpatient claim for bipolar disorder, when the visit accounted for at least 50 percent of all outpatient mental health visits. ( ICD-9 diagnostic codes for bipolar disorder are 296.0-296.1, 296.4-296.8, 301.11, and 301.13.) Enrollees with an inpatient diagnosis of schizophrenia were excluded because of the likelihood that inpatient discharge diagnoses represent diagnoses based on more information and observation time than those of an outpatient visit.

Once the bipolar cohort was determined, persons who received at least one claim with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder ( ICD-9 diagnostic codes: 296.0, 296.2, and 296.4-296.7) were included in our cohort of bipolar I disorder. We selected bipolar I disorder rather than the entire population with bipolar disorder because we were concerned that other bipolar spectrum disorder diagnoses, with their more subtle clinical presentations, would not be as accurate in claims data analyses as would bipolar I diagnoses and because the guidelines are less clear as to whether all persons with other bipolar spectrum disorders require maintenance treatment with lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine.

We did not have information regarding the enrollment dates for participants. Instead, we determined the observation period by using the first and last procedure code claims (mental health, including substance use disorder, and general medical) for each of the study years as a proxy for enrollment. We limited our analyses to persons who had administrative claims that spanned at least ten months in a given year (86.4 percent of the bipolar I population) and to persons who were between ages of 18 and 64 years. Further, we limited our analyses to persons who were seeking treatment for their bipolar disorder. Therefore, they were required to have at least one claim with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder in a given year to be included in that year's cohort. Finally, because we included pharmacotherapy measures in our quality indicators, we limited our cohort to adults diagnosed as having bipolar disorder by a psychiatrist in a given year.

Quality measures

The 1994 APA Practice Guideline for the treatment of bipolar disorder ( 18 ) informed the medication and psychotherapy process measures of quality. The medication measures were consistent with other pharmacotherapy guidelines for bipolar disorder published until year 2002 ( 6 , 19 , 20 ). Although the guidelines recommend maintenance treatment with lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine, we used a minimum threshold for these measures as a liberal estimate of quality—that is, whether or not individuals received at least one prescription. These medications were selected because they were recommended by guidelines during the study period.

We used guideline publication as a marker for consensus in the literature regarding treatment quality. Although not all prescribing clinicians may read a particular guideline, guideline publication signals that the information is available in the literature to inform practice. The 1994 APA guidelines recommend psychotherapy based on the clinical needs of the patient. Because our analyses are in person-years, we anticipated that we would be observing treatment through periods of both acute mood destabilization and maintenance phase treatment. For these reasons, as well as the chronic and debilitating nature of bipolar disorder, we felt it was a reasonable expectation that persons in this cohort would have at least one session of psychotherapy—whether it be individual, group, or family therapy.

Statistical methods

Separate logistic regression models were fit for each quality measure. The measures we selected were the likelihood of receiving any therapy; any lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine; both therapy and a medication, such as lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine; and an antidepressant in the absence of lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine (a measure advised against in the guidelines). Current Procedural Terminology (CPT-4) procedure codes from inpatient and outpatient claims were used to identify the receipt of the psychotherapeutic interventions. The psychopharmacological interventions were identified through the National Drug Code number reported on drug claims.

Explanatory variables

Explanatory variables in the models included demographic characteristics (for example, age, gender, and whether the person was an employee or a relative of the employee), co-occurring substance use disorders, and other co-occurring psychiatric and medical conditions that may affect treatment choices or complicate treatment or outcomes.

The co-occurring psychiatric disorders that were included were ICD-9 codes for psychiatric diagnoses (290-311) with the exception of depressive disorders (296.2, 296.3, 300.4, 301.12, 309.1, and 311) and psychotic disorders (297 and 298), because these would more likely represent bipolar disorder symptoms than co-occurring disorders. Moreover, codes for dementia (331 and 797) were included. Because bipolar disorder can be initially misdiagnosed as other types of psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and attention-deficit hyperactive disorder, we considered co-occurring psychiatric disorders to be present only if there were two such claims for these diagnoses observed after the first bipolar disorder claim. This was done to minimize false positive co-occurring diagnoses in the claims data. However, the accuracy of a diagnosis of substance use disorder is unlikely to be dependent upon the timing of a bipolar diagnosis. Therefore, our criterion for substance use disorders was the presence of two claims with a diagnosis of substance use disorder occurring either before or after the first bipolar diagnosis.

Nonpsychiatric co-occurring conditions that are also thought likely to complicate the treatment of bipolar disorder were included. They were diagnoses of cardiovascular disorders, renal disorders, hepatic disorders, thyroid disorders, inflammatory disorders, hypertension, diabetes or obesity, pregnancy, migraine headaches, and neurological disorders that could affect cognition, such as HIV, brain tumors, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, cerebrovascular accident, seizure disorder, and anoxic brain damage. As with the determination of the co-occurring mental health or substance use disorders, general medical co-occurring conditions were required to have a confirmatory diagnosis in the claims.

We controlled for varying durations that individuals were observed each study year (that is, from ten to 12 months) by including the length of time observed as a covariate in the regression model.

This study received approval from the Harvard Medical School Institutional Review Board.

Results

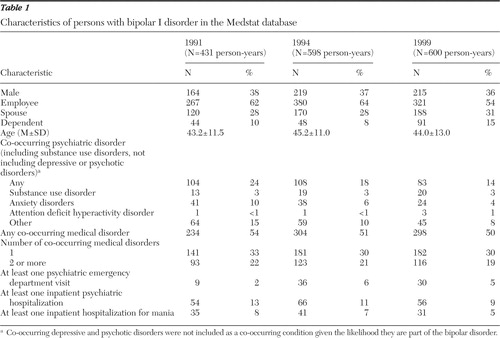

The sample sizes were 431, 598, and 600 person-years in 1991, 1994, and 1999, respectively. Table 1 describes population demographic and clinical characteristics. There was a high prevalence of both co-occurring medical and psychiatric conditions. Our observed prevalence of co-occurring substance use disorder (approximately 3 percent of our bipolar I disorder cohort) is consistent with the proportion seen in the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Disorder Research Network (4 percent) ( 21 , 22 , 23 ). Across years, the prevalence of co-occurring disorders declined.

|

The proportion receiving a mental health hospitalization also declined over time. However, when compared with the rise in mental health visits to the emergency department, it appears that a similar proportion were "in crisis," despite the declines in hospitalization.

Approximately two-thirds of the population received lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine in 1991 and 1994; the proportion increased to 77 percent in 1999 ( Table 2 ). Also, the proportion receiving an antidepressant steadily increased over the study years. In contrast, 94 percent received at least one therapy session in 1991; this number dropped to 69 percent in 1999. When combinations of the quality measures are considered, it is evident that measures combining therapy and lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine declined across time. Measures of poor-quality care—such as receiving an antidepressant without lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine—increased between 1991 and 1994 but then declined in 1999. The proportion who received no therapy or lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine increased across time.

|

Table 3 describes the logistical regression results across the four quality-measure models. The patterns of change differ across the quality measures. The likelihood of receiving lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine (independent of receiving therapy) improved in 1994 and 1999, whereas the likelihood of receiving any therapy declined in both years but more sharply in 1999. The likelihood of receiving both psychotherapy and lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine declined after 1991. However, prescribing antidepressants without lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine sharply increased in 1994 but in 1999 declined and was similar to the 1991 levels.

|

Discussion

Several aspects of these results are worth noting. Despite the observed improvements in quality of care, there is room for further improvement. In particular, the sharp decline in the likelihood of receiving psychotherapy is concerning. Although it is unclear what frequency or duration of therapy would be appropriate, it seems reasonable that receiving at least one session in a given year would have therapeutic value, given the chronic and disabling nature of bipolar I disorder.

The pharmacotherapy-specific measures indicated improvements in quality over time. In the case of antidepressant prescribing, this improvement represented a reverse in the trend observed in 1994. These changes likely have at least one of two explanations. In 1996 valproate received approval from the Food and Drug Administration for acute mania. Thus the increase in lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine prescribing may be explained by the expansion of treatment options. Also, over the course of this time series, there was increasing consensus in the literature as to appropriate pharmacotherapy for bipolar disorder. This increased consensus could account for improved quality in lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine and antidepressant prescribing for bipolar disorder. This analysis did not include pharmacotherapy measures recommended by guidelines after the year 2002. The addition of newer pharmacotherapies with demonstrated bipolar disorder efficacy—such as lamotrigine and second-generation antipsychotics, including risperidone and olanzapine—likely would have magnified the improvements we observed over time in maintenance-phase pharmacotherapy for bipolar I disorder.

There was a decline in the likelihood of receiving any psychotherapy in 1994 and a further, sharper decline in 1999. It is possible that the decline in psychotherapy is due to differences in patient characteristics over time. In our data, compared with 1991, the bipolar I detection rate increased by 39 percent in 1994 (similar comparison is not possible for 1999 since it is a sample matched to 1994). However, with the exception of a decline in co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses across time, there is little difference in the observable patient characteristics in our cohort (which were also controlled for in the regression model). Still, patients may have differed in unobservable characteristics. However, these characteristics would not have affected this measure because at least one psychotherapy session in a given year would be reasonable. Additionally, these results are consistent with those of other studies that demonstrate a decline in psychotherapy for psychiatric illnesses, such as depression and schizophrenia ( 24 , 25 ). Thus there is literature suggesting that our results are due to circumstances independent of the clinical characteristics of the patients in this study.

The decline in psychotherapy may represent a substitution of CPT-4 coding by psychiatrists without a real change in the visit content—that is, rather than coding for psychotherapy, psychiatrists are billing for medication management but are also providing psychotherapy. However, we believe that this is unlikely given the financial disincentive for psychiatrists to provide psychotherapy compared with medication management ( 26 ). It would also be difficult to provide medication management and psychotherapy with demonstrated efficacy for bipolar disorder in the time constraints of a medication management visit. Although we cannot know that the psychotherapy coded as such in these claims also adheres to this evidence base, we know at least that psychotherapy is coded as being provided in that visit. This is not the case with psychotherapy delivered in a 90862 CPT code; in that circumstance the procedure is much less likely to conform to evidence-based practice. Finally, as previously mentioned, our results showing that psychotherapy visits declined over time are consistent with other literature ( 24 , 25 ). Hence, the likelihood of changes in coding without changes in the actual services provided during the visits is unlikely.

Prior studies examining the effect of managed behavioral health care in treatment utilization specifically for major depression have observed a shift away from psychotherapy and toward increased antidepressant utilization ( 24 , 27 , 28 ). Some investigators interpret these results as indicating there is a "substitutability" between the two treatment modalities for depression ( 27 , 28 )—that is, that therapy to at least some extent can be replaced by medication. However, our results suggest, at least for bipolar disorder, another possible explanation of the forces guiding treatments received. Our pharmacotherapy measures included one measure that recommends prescribing a medication (that is, lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine) and another that required refraining from a poor quality measure (that is, prescribing an antidepressant without lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine). Both of these measures improved over time, whereas the therapy indicator worsened. On the basis of these results, an alternative hypothesis is that psychosocial treatments are constrained in ways that pharmacotherapies are not—rather than the hypothesis that pharmacotherapy acts as a substitute for psychotherapy.

It is also important to note that although one would expect to see similar results in managed behavioral health carve-out arrangements (because carve-outs typically are not financially at risk for pharmacotherapy but are for inpatient and outpatient visit utilization), these enrollees were served under a variety of insurance arrangements. The care of some, but not all, enrollees was managed by carve-outs. Regardless of the insurance arrangement for delivering the mental health care, this analysis indicates different psychotherapeutic modalities are under different constraints and respond to these constraints differently.

Our results differ from those of Blanco and colleagues ( 12 ), who found no change in pharmacotherapy prescribing between 1992 and 1999 of non-dopamine-blocking antimanic agents (that is, lithium or anticonvulsants) and of antidepressants in the absence of lithium or anticonvulsant agents. Although both studies were similar in that bipolar diagnoses were determined by psychiatrists and occurred over similar study years, the two studies used different methodologies and are not directly comparable. Additionally, Blanco and colleagues employed an expanded definition of non- dopamine-blocking antimanic agents by including gabapentin, topiramate, and lamotrigine—three medications that as of 1999 had unclear therapeutic efficacy for bipolar disorder.

It is also notable that in this cohort of persons with bipolar I disorder, there was an improvement in guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy over time. Although one cannot assume that these improvements are directly attributable to the guidelines, guideline publication does signal an increasing consensus in the medical literature, as well as promotes awareness of that consensus. These observed improvements are in contrast to other medical conditions and procedures, such as diabetes or cesarean section rates, for which guideline publication has not been previously associated with improvements in clinician practice ( 29 , 30 ). Similarly, in the treatment of other psychiatric illnesses, the literature suggests that guideline publication has rarely been associated with improvements in clinician practice ( 31 ).

This study has several limitations. It used administrative claims to identify persons with bipolar I disorder. Although structured interviews with patients and chart reviews have greater accuracy in establishing a bipolar cohort, Unützer and colleagues ( 14 , 17 ) demonstrated that claims data have demonstrated validity in analyses utilizing a bipolar diagnosis to establish the cohort and assess population-based quality of care. We used more stringent criteria in our cohort algorithm than Unützer and colleagues. Finally, although our algorithm was developed to balance maximizing the "true positive" rate while minimizing the "false negative" rate, it is likely that there are persons with bipolar I disorder who were not given the diagnosis in the claims, and therefore, we cannot comment on the quality of care for those enrollees.

Furthermore, the literature points to specific psychotherapies, such as psychoeducation and cognitive-behavioral therapy, as having demonstrated efficacy in treating bipolar disorder ( 32 ). However, information about the content of psychotherapy is not obtainable in claims data, nor is it obtainable from chart review. Thus we cannot know if the psychotherapy services delivered to this cohort would have been these efficacious treatments. Still, it seems reasonable to expect, given the highly debilitating and chronic nature of bipolar disorder, that patients would receive at least one psychotherapeutic session that could provide psychoeducation to the patient or to his or her family.

Another limitation is that although these quality indicators were informed by published bipolar disorder guidelines, they are very loose indicators of quality, setting a minimum benchmark of whether patients received at least one prescription or therapy session. We did not measure the dosage or duration of these treatments.

Conclusions

These results indicate that quality measures of different therapeutic modalities respond differently to different pressures. Our data demonstrate that across study years pharmacologic measures improved while psychosocial measures declined. This decline in psychotherapy is consistent with changes observed in studies of depression and schizophrenia care as well. Thus, when resources are constrained in a variety of ways, promulgating guidelines or achieving consensus in the medical literature is clearly not enough to improve quality. Often, quality assessment focuses on pharmacotherapy measures. This analysis demonstrates that measuring a variety of therapeutic modalities is important in psychiatric quality assessment if policy makers are to make rational decisions regarding the adequacy of care in their population.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from grant R01-MH-62028 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (Dr. Busch, Dr. Ling, Dr. Frank, and Dr. Greenfield), grant R01-MH-069721 from NIMH (Dr. Busch and Dr. Frank), grant K01-MH-071714 from NIMH (Dr. Busch), subcontract 98 DS 001 from NIMH's Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder study (Dr. Busch), grant R01-MH-59254 from NIMH (Dr. Frank), and grants K08-DA-00407 and K24-DA-019855 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Dr. Greenfield). Also, additional funding was provided for Dr. Busch by the Dr. Ralph and Marian Falk Medical Research Trust and the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The funding organizations had no role in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data. They also had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Suppes T, Leverich GS, Keck PE, et al: The Stanley Foundation bipolar treatment outcome network. II: demographics and illness characteristics of the first 261 patients. Journal of Affective Disorders 67:45-59, 2001Google Scholar

2. Coryell W, Scheftner W, Keller M, et al: The enduring psychosocial consequences of mania and depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:720-727, 1993Google Scholar

3. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al: The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:530-537, 2002Google Scholar

4. Tsai S-YM, Chen C-C, Kuo C-J, et al: 15-year outcome of treated bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 63:215-220, 2001Google Scholar

5. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR: Manic-Depressive Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

6. Bowden CL, Gitlin MJ, Keck PE, et al: Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). American Journal of Psychiatry 159(suppl):1-50, 2002Google Scholar

7. Simon GE, Unützer J: Health care utilization and costs among patients treated for bipolar disorder in an insured population. Psychiatric Services 50:1303-1308, 1999Google Scholar

8. Peele PB, Xu Y, Kupfer DJ: Insurance expenditures on bipolar disorder: clinical and parity implications. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1286-1290, 2003Google Scholar

9. Li J, McCombs JS, Stimmel GL: Cost of treating bipolar disorder in the California Medicaid (Medi-Cal) program. Journal of Affective Disorders 71:131-139, 2002Google Scholar

10. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, et al: Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? Journal of Affective Disorders 52:135-144, 1999Google Scholar

11. Lim PZ, Tunis SL, Edell WS, et al: Medication prescribing patterns for patients with bipolar-I disorder in hospital settings: adherence to published practice guidelines. Bipolar Disorders 3:161-173, 2001Google Scholar

12. Blanco C, Laje G, Olfson M, et al: Trends in the treatment of bipolar disorder by outpatient psychiatrists. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1005-1010, 2002Google Scholar

13. Marcus SC, Olfson M, Pincus HA, et al: Therapeutic drug monitoring of mood stabilizers in Medicaid patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1014-1018, 1999Google Scholar

14. Unützer J, Simon G, Pabiniak C, et al: The use of administrative data to assess quality of care for bipolar disorder in a large staff model HMO. General Hospital Psychiatry 22:1-10, 2000Google Scholar

15. Mechanic D, McAlpine DD: Mission unfulfilled: pot holes on the road to parity. Health Affairs 18(5):7-21, 1999Google Scholar

16. Frank RG, Lave JR: Economics in Managed Behavioral Health Services. Edited by Feldman S. Springfield, Ill, Thomas, 2003Google Scholar

17. Unützer J, Simon G, Pabiniak C, et al: The treated prevalence of bipolar disorder in a large staff-model HMO. Psychiatric Services 49:1072-1078, 1998Google Scholar

18. Hirschfeld RM, Bowden CL, Gitlin MJ, et al: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 151(suppl):1-36, 1994Google Scholar

19. Sachs GS, Printz D, Kahn D, et al: The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: Medication Treatment of Bipolar Disorder 2000. Postgraduate Medicine (spec):1-104, 2000Google Scholar

20. Bauer MS, Callahan AM, Jampala C, et al: Clinical practice guidelines for bipolar disorder from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:9-21, 1999Google Scholar

21. Goldman HH, Morrissey JP, Ridgely S, et al: Lessons from the program on chronic mental illness. Health Affairs 11(3):52-68, 1992Google Scholar

22. Suppes T, Leverich GS, Keck J, et al: The Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Outcome Network. II: demographics and illness characteristics of the first 261 patients. Journal of Affective Disorders 67:45-59, 2001Google Scholar

23. McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Suppes T, et al: Axis I psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship to historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:420-426, 2001Google Scholar

24. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, et al: National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA 287:203-209, 2002Google Scholar

25. Busch AB, Frank R, Lehman AF: Effect of a Medicaid managed behavioral health carve-out on quality of care for persons diagnosed as having schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:442-448, 2004Google Scholar

26. West JC, Wilk JE, Rae DS, et al: Financial disincentives for the provision of psychotherapy. Psychiatric Services 54:1582-1588, 2003Google Scholar

27. Berndt ER, Frank RG, McGuire TG: Alternative insurance arrangements and the treatment of depression: what are the facts? American Journal of Managed Care 3:243-250, 1997Google Scholar

28. Busch SH, Berndt ER, Frank RG: Creating price indexes for measuring productivity in mental health care, in Frontiers in Health Policy Research: Vol 4. Edited by Gerber AM. Cambridge, National Bureau of Economics Research, 2001Google Scholar

29. Lomas J, Anderson GM, Domnick-Pierre K, et al: Do practice guidelines guide practice? The effect of a consensus statement on the practice of physicians. New England Journal of Medicine 321:1306-1311, 1989Google Scholar

30. Stolar MW: Clinical management of the NIDDM patient: impact of the American Diabetes Association Practice Guidelines. Diabetes Care 18:701-707, 1995Google Scholar

31. Bauer M: A review of quantitative studies of adherence to mental health clinical practice guidelines. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 10:138-153, 2002Google Scholar

32. Vieta E, Colom F: Psychological interventions in bipolar disorder: from wishful thinking to an evidence-based approach. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, Supplementum 422:34-8, 2004Google Scholar